By Tim O’Shea

Source: Information Clearing House

Aldous Huxley’s inspired 1954 essay detailed the vivid, mind-expanding, multisensory insights of his mescaline adventures. By altering his brain chemistry with natural psychotropics, Huxley tapped into a rich and fluid world of shimmering, indescribable beauty and power. With his neurosensory input thus triggered, Huxley was able to enter that parallel universe glimpsed by every mystic and space captain in recorded history. Whether by hallucination or epiphany, Huxley sought to remove all bonds, all controls, all filters, all cultural conditioning from his perceptions and to confront Nature or the World or Reality first-hand – in its unpasteurized, unedited, unretouched infinite rawness.

Those bonds are much harder to break today, half a century later. We are the most conditioned, programmed beings the world has ever known. Not only are our thoughts and attitudes continually being shaped and molded; our very awareness of the whole design seems like it is being subtly and inexorably erased. The doors of our perception are carefully and precisely regulated.

It is an exhausting and endless task to keep explaining to people how most issues of conventional wisdom are scientifically implanted in the public consciousness by a thousand media clips per day. In an effort to save time, I would like to provide just a little background on the handling of information in this country. Once the basic principles are illustrated about how our current system of media control arose historically, the reader might be more apt to question any given story in today’s news.

If everybody believes something, it’s probably wrong. We call that

CONVENTIONAL WISDOM

In America, conventional wisdom that has mass acceptance is usually contrived. Somebody paid for it. Examples:

-

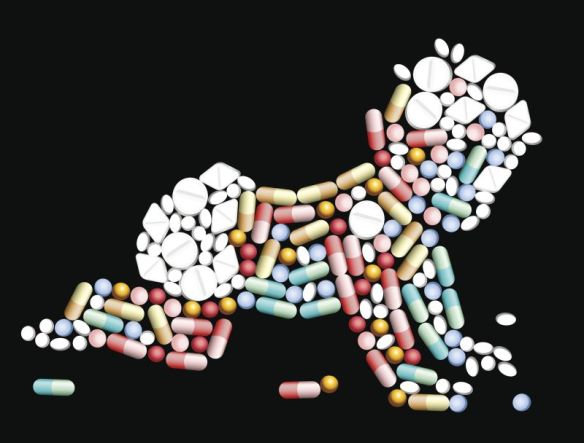

Pharmaceuticals restore health

-

Vaccination brings immunity

-

The cure for cancer is just around the corner

-

Menopause is a disease condition

-

Childhood is a disease condition

-

When a child is sick, he needs immediate antibiotics

-

When a child has a fever he needs Tylenol

-

Hospitals are safe and clean

-

America has the best health care in the world.

-

Americans have the best health in the world.

-

The purpose of Health Care is health.

-

Milk is a good source of calcium.

-

You never outgrow your need for milk.

-

Vitamin C is ascorbic acid.

-

Aspirin prevents heart attacks.

-

Heart drugs improve the heart.

-

Back and neck pain are the only reasons for spinal adjustment.

-

No child can get into school without being vaccinated.

-

The FDA thoroughly tests all drugs before they go on the market.

-

Pregnancy is a serious medical condition

-

Infancy is a serious medical condition

-

Chemotherapy and radiation are effective cures for cancer

-

When your child is diagnosed with an ear infection, antibiotics should be given immediately ‘just in case’

-

Ear tubes are for the good of the child.

-

Estrogen drugs prevent osteoporosis after menopause.

-

Pediatricians are the most highly trained of al medical specialists.

-

The purpose of the health care industry is health.

-

HIV is the cause of AIDS.

-

Without vaccines, infectious diseases will return

-

Fluoride in the city water protects your teeth

-

Flu shots prevent the flu.

-

Vaccines are thoroughly tested before being placed on the Mandated Schedule.

-

Doctors are certain that the benefits of vaccines far outweigh any possible risks.

-

There is a terrorist threat in the US.

-

The NASDAQ is a natural market controlled by supply and demand.

-

Chronic pain is a natural consequence of aging.

-

Soy is your healthiest source of protein.

-

Insulin shots cure diabetes.

-

After we take out your gall bladder you can eat anything you want

-

Allergy medicine will cure allergies.

-

Your government provides security.

-

The Iraqis blew up the World Trade Center.

Wikipedia is completely open, unbiased, and interactive

This is a list of illusions, that have cost billions to conjure up. Did you ever wonder why most people in this country generally accept most of the above statements?

PROGRAMMING THE VIEWER

Even the most undiscriminating viewer may suspect that TV newsreaders and news articles are not telling us the whole story. The slightly more lucid may have begun to glimpse the calculated intent of standard news content and are wondering about the reliability and accuracy of the way events are presented. For the very few who take time to research beneath the surface and who are still capable of abstract thought, a somewhat darker picture begins to emerge. These may perceive bits of evidence of the profoundly technical science behind much of what is served up in daily media.

Events taking place in today’s world are enormously complex. An impossibly convoluted tangle of interrelated and unrelated occurrences happens simultaneously, often in dynamic conflict. To even acknowledge this complexity contradicts a fundamental axiom of media science: Keep It Simple.

In real life, events don’t take place in black and white, but in a thousand shades of grey. Just discovering the actual facts and events as they transpire is difficult enough. The river is different each time we step into it. By the time a reasonable understanding of an event has been apprehended, new events have already made that interpretation obsolete. And this is not even adding historical, social, or political elements into the mix, which are necessary for interpretation of events. Popular media gives up long before this level of analysis.

Media stories cover only the tiniest fraction of actual events, but stupidly claim to be summarizing “all the news.”

The final goal of media is to create a following of docile, unquestioning consumers. To that end, three primary tools have historically been employed:

deceit

dissimulation

distraction

Over time, the sophistication of these tools of propaganda has evolved to a very structured science, taking its cues in an unbroken line from principles laid down by the Father of Spin himself, Edward L Bernays, over a century ago, as we will see.

Let’s look at each tool very briefly:

DECEIT

Deliberate misrepresentation of fact has always been the privilege of the directors of mass media. Their agents – the PR industry – cannot afford random objective journalism, interpreting events as they actually take place. This would be much too confusing for the average consumer, who has been spoonfed his opinions since the day he was born. No, we can’t have that. In all the confusion, the viewer might get the idea that he is supposed to make up his own mind about the significance of some event or other. The end product of good media is single-mindedness. Individual interpretation of events does not foster the homogenized, one-dimensional lemming outlook.

For this reason, events must have a spin put on them – an interpretation, a frame of reference. Subtleties are omitted; all that is presented is the bottom line. The minute that decision is made – what nuance to put on a story – we have left the world of reporting and have entered the world of propaganda. By definition, propaganda replaces faithful reporting with deceitful reporting.

Here’s an obvious example from the past: the absurd and unremitting allegations of Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction as a rationale for the invasion of Iraq. Of course none were ever found, but that is irrelevant. We weren’t really looking for any weapons – but the deceit served its purpose – get us in there. Later the ruse can be abandoned and forgotten; its usefulness is over. And nobody will notice. Characterization of Saddam as a murderous tyrant was decided to be an insufficient excuse for invading a sovereign nation. After all, there are literally dozens of murderous tyrants the world over, going their merry ways. We can’t be expected to police all of them.

So it was decided that the murderous tyrant thing, though good, was not enough. To whip a sleeping people into war consciousness has historically involved one additional prerequisite: threat. Saddam must therefore be not only a baby-killing maniac; he must be a threat to the rest of the world, especially America. Why? Because he has weapons of mass destruction. For almost two years, this myth was assiduously programmed into that lowest common denominator of awareness which Americans substitute for consciousness. Even though the myth has now been openly dismissed by the Regime itself, the majority of us still believe it.

Hitler used the exact same tack with the Czechs and Poles at the beginning of his rampage. These peaceful peoples were not portrayed as an easy mark for the German war machine – no, they were a threat to the Fatherland itself. Just like the unprovoked Chinese annihilation of the peaceful Tibetan civilization in the 1940s. Or like Albania in the Dustin Hoffman movie. Such threats must be crushed by all available force, under the pretext used by every strong nation in history to subjugate a weaker one.

With Iraq, the fact that UN inspectors never came up with any of these dread weapons before Saddam was captured – this fact was never mentioned again. That one phrase – WMD WMD WMD – repeated ad nauseam month after month had served its purpose – whip the people into war mode. It didn’t have to be true; it just had to work. A staggering indicator of how low the general awareness had sunk is that this mantra continued to be used as our license to invade Iraq long after our initial assault. If Saddam had any such weapons, probably a good time to trot them out would be when a foreign country is moving in, wouldn’t you say?

No weapons were ever found, of course, nor will they be. So confident was the PR machine in the general inattention to detail commonly exhibited by the comatose American people that they didn’t even find it necessary to plant a few mass weapons in order to justify the invasion. It was almost insulting. Now nobody asks any more. In 2010 a poll of US soldiers in Iraq showed 60% believed the Iraqis blew up the World Trade Center.

So we see that a little deceit goes a long way. All it takes is repetition. Lay the groundwork and the people will buy anything. After that just ride it out until they seem doubtful again. Then onto the next deceit.

SELLING WAR

Did you ever wonder how all the war leaders down through history were able to persuade armies of thousands as individuals to leave their homes and families and risk their lives for vague, obscure reasons? How do they sell that? How do you get people to go off to war?

With rare exceptions, it’s been the same formula right down the line: sell idealistic young men the lie of the glory of war, defending their country and home from some imaginary enemy, some contrived foreign threat, from a place of alien culture. Then any oppposition to the ‘war effort’ are then lily-livered, unpatriotic, etc. Patriotism – the last refuge of a scoundrel.

Hermann Goering summarized it eloquently at Nuremberg:

‘Why of course the people don’t want war. Why should some poor slob on a farm want to risk his life in a war when the best he can get out of it is to come back to his farm in one piece? Naturally the common people don’t want war; neither in Russia, nor in England, nor in America, nor in Germany. That is understood. But after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine policy, and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy, or a fascist dictatorship, or a parliament, or a communist dictatorship. Voice or no voice the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is to tell them they are being attacked, and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same in any country.’

This technique holds true right up to the present time, intensified exponentially by the magnitude of incessant, pervasive online media. Worked great for Bush and Obama in their marketing of war.

DISSIMULATION

A second tool that is commonly used to create mass intellectual torpor is dissimulation. Dissimulation simply means to pretend not to be something you are. Like phasmid insects who can disguise themselves as leaves or twigs, pretending not to be insects. Or bureaucrats and who pretend not to be acting primarily out of self-interest, but rather in the public interest. To pretend not to be what you are.

Public servant, indeed.

Whether it’s the Bush/Obama in Iraq or Hitler in Germany, aggressors do not present themselves as marauding invaders initiating hostilities, but instead as defenders against external threats.

Freedom-annihilating edicts like the Homeland Security Act and the Patriot Act – still the law of the land – do not represent themselves as the negation of every principle the Founding Fathers laid down, or as shaky pretexts for looting the country, but rather as public services, benevolent and necessary new rules to ensure our SECURITY against various imagined enemies. To pretend to be what you are not: dissimulation.

Other examples of dissimulation we see today include:

-

pretending like the world’s resources are not finite

-

pretending like more and more government will not further stifle an already struggling economy

-

pretending like programs favoring “minorities” are not just a different form of racism

-

pretending like drug laws are necessary for national security

-

pretending like passing more and more laws every year is not geared ultimately for the advancement of the law enforcement, security, and prison industries

-

pretending there is a bioterrorist threat in the US today

-

pretending there is a terrorist threat in the US today

pretending the present regime has not benefited from every program that came out of 9/11

To pretend not to be what you are: dissimulation.

DISTRACTION

A third tool necessary to media in order to keep the public from thinking too much is distraction. Bread and circuses worked for Caesar in old Rome. Marie Antoinette offered cake when there was no bread. The people need to be kept quiet while the small group in power carries out its agenda, which always involves fortifying its own position.

Virtually all new policies of the regimes since 9/11 may be explained by plugging in one of four beneficiaries:

Every act, every political event, every bill introduced, every public statement of the present administration has promoted one or more of these huge sectors. More oil, more drugs, more weapons, more security.

But the people mustn’t be allowed to notice things like that. So they must be smokescreened by other stuff, blatant obvious stuff which is really easy to understand and which they think has a greater bearing on their day to day life. A classic axiom of propaganda is that people shouldn’t be allowed to think too much about what the government is doing in their name. After all, there’s more to life than politics, right? So while the power group has its cozy little wars and agendas going on, the people need to have their attention diverted.

All the strongmen of history would have given their eyeteeth to have at their disposal the number and types of distractions available to today’s regimes:

-

TV sports, its orchestrated frenzy and spectacle, where the fix is usually in

Super Sunday

the endless succession of unspeakably boring, inane movies, short on plot, long on CGI, re-working the same 20 premises, over and over

the wanton sexless flash of ‘talent shows’ with their uninspired lack of talent, a study in split second phony images

colossally dull TV programs which serve the secondary purpose of instilling proper robot attitudes into people who have little other instruction in life values

the artistic Mojave of modern music, with its soulless cyber-droning, a constant quest for the nadir of reptilian brain stimulation, devoid of lyrical competence, instrumental proficiency, or human passion

the ever-retreating promise of financial success, switched now to the trappings and toys that suggest success, available to anyone with a credit card

organized superstitions of all varieties, with their requisite pseudo-spiritual trappings

the constant sensationalization of crimes and “issues” throughout the world whose collective goal is the humble and grateful acknowledgement of “how good we’ve really got it”

dwelling for months on the minutiae of unsupported allegations of impropriety, preferably sexual, of a celebrity personality

non-events presented as events, brought to life by media alone, employing one of the Big Three hooks: sex, blood, and racism

With these ceaseless noisy, banal distractions, the forces promoting the general decline in intelligence and awareness jubilantly engulf us on all sides. Media science holds the advantage: as people get dumber and dumber year by year, it gets easier and easier to keep them dumb. The only challenge is that their threshold keeps getting lower. So in order to keep their attention, messages have to become more obvious and blatant, taking nothing for granted.

Here are some indicators of our declining intelligence:

-

– flagrant errors of grammar and spelling rampant in advertising, which go unnoticed

– declining SAT scores and the arbitrary resetting of Average, which has occurred at least twice in the past 8 years, in order to cover up how dumb our kids are really getting

– forcing the the dumbed-down Common Core philosophy upon American elementary schools

– increased volume and decreased speed of the voices of newsreaders on radio and TV

– the limited vocabulary and clichéd speech allowed in radio programs; the obvious lack of education and requisite pedestrian mentality required of the corporate simians who are featured on radio

– increasing illiteracy of high school graduates, both written and spoken

– the unwritten policy requiring school teachers, especially math and English teachers, to pass students who have failing marks, especially if they’re a certain race or other, so that the school won’t “look bad”

– decreasing requirements for masters theses and PhD dissertations in both length and content

– increasing oversimplification of movie and TV plot lines – absence of subtlety in conceptual and dramatic content; blatant moralizing of compliant robot values

– the speed at which images on TV are flashed, giving the viewer barely enough time to recognize which sledgehammer idea they are referring to before the next one appears, about 2 seconds later. That way there is no possible way the brain can follow a train of thought in any kind of depth. From childhood the brain learns that it is not to be tasked with understanding abstractions or concepts of any subtlety from the information presented. All the brain has to do is react to the incessant bombardment of fragmented ADD-generating visual stimuli without trying to derive sense or logic from it. This is why TV should be watched only with the sound off, since it has generally the same educational value as a lava lamp.

– the enormous proportion of time spent by TV channels telling the viewer what will be shown in the future, leaving no time for actually delivering what they have already endlessly promised in the recent past, which should be airing at the present moment.

– newspaper articles that are not written by reporters but that are scientifically crafted phrase by canny phrase by the PR industry and placed into the columns of syndication in the guise of ‘hard news’

– the recent removal of the basic science prerequisites for US chiropractic schools, which had been in place for 50 years

– Jerky, clumsy news clips, loaded with coarse innuendo and nonsequitur, ridiculously brief: most news clips evoke only the most superficial suggestion of events which may or may not have transpired, resulting generally in the transfer of no information

– the downward spiral of the level of ordinary conversations, which are commonly just exercises in stringing together random clichés from the very finite stock of endlessly repeated homogeneous bytes. It’s as though we’re only allowed to have 50 thoughts, and most conversation is just linking these 50 programmed audio clips together in a different order: America becomes our own private Sicily

– in popular music the overriding absence of melody, lyric, chord complexity, or instrumental competence

– increase in mandating neurotoxic drugs and vaccines with new laws and regulations

TERRORISTS ARE US?

Imagine for a moment that 9/11 was a put-up job engineered for the sole purpose of cementing the current regime into power and frightening the bovine populace into surrendering even more of what little freedom they have left. Hypothetical situation now, just work with me a little. Imagine there never were any dissident crazed terrorists representing Osama or Saddam, but instead a highly disciplined though slightly whacked-out team of military special forces, programmed somehow to think they were doing something valuable for some faction or other. A put-up job, from the inside.

So then imagine that all the violence and stress perpetrated on the collective American psyche since 9/11 about war, bioterrorism, and security has all been completely unnecessary. And that all the trillions of dollars of extra security and wasted time in airports and borders was also totally unnecessary because there never were any terrorists, except us. And all the shrill media articles and “stories” that support the few underlying events have been unnecessary, their prime purpose being self promotion. Think how much our quality of life has suffered. What if all this stress has been totally unnecessary?

Many of our best people have come to precisely these conclusions. Once you got past the initial hurdle of being able to consider the unthinkable possibility that the present regime could be so obsessed with gaining political advantage that they would actually blow up 3000 of our own people, the rest falls into place. Over the top? Not such a stretch really when you compare the thousands that have been sacrificed to the whims of other blood-mad tyrants the world over, throughout all of recorded history. Exactly how are we any better?

WHAT DO WE REALLY KNOW?

When it comes to a discussion of what’s going on in the world, the honest individual must admit that he has almost no idea. When was the last time Obama invited you into the Green Room for a private chat with Cheney and Hagel about the future of big oil? When did Bill Gates last invite you up to his Redmond digs for a wine and cheese brainstorming session about the next Big Thing? Or when did your neighbor who lives three blocks away from you call you up to tell you about the unfulfilled plans of his father who just found out he’s dying of cancer? How many life stories of the world’s seven billion people do you know anything about?

This is to say nothing of fluid events which are coming in and out of existence every day between the nations of the world that only the few ever hear about. What is really going on? Much more effort is spent covering up and packaging actual events that are taking place than in trying to accurately report and evaluate them. These are questions of epistemology: what can we know? The answer is: very little, if our only source of information is the superficial everyday media. The few people who buy books don’t read them. Passive absorption of pre-interpreted already-figured-out data is the preferred method

HOW IT ALL GOT STARTED

But wait, we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s back up a minute. In their book Trust Us We’re Experts, Stauber and Rampton pull together some compelling data describing the science of creating public opinion in America. They trace modern public influence back to the early part of the last century, highlighting the work of guys like Edward L. Bernays, the Father of Spin.

From his own amazing 1920s books – Propaganda, and Crystallizing Public Opinion – we learn how Edward L. Bernays took the ideas of his famous uncle Sigmund Freud himself, and applied them to the emerging science of mass persuasion. The only difference was that instead of using these principles to uncover hidden themes in the human unconscious, the way Freudian psychology does, Bernays studied these same ideas in order to learn how to mask agendas and to create illusions that deceive and misrepresent, for marketing purposes.

THE FATHER OF SPIN

Edward L. Bernays dominated the PR industry until the 1940s, and was a significant force for another 50 years after that. (Tye) During that time, Bernays took on hundreds of diverse assignments to create a public perception about some idea or product. A few examples:

As a neophyte with the Committee on Public Information, one of Bernays’ first assignments was to help sell the First World War to the American public with the idea to “Make the World Safe for Democracy.” (Ewen) We’ve seen this phrase in every war and US military involvement since that time.

A few years later, Bernays set up a stunt to popularize the notion of women smoking cigarettes. In organizing the 1929 Easter Parade in New York City, Bernays showed himself as a force to be reckoned with. He organized the Torches of Liberty Brigade in which suffragettes marched in the parade smoking cigarettes as a mark of women’s liberation. After that one event, women would be able to feel secure about destroying their own lungs in public, the same way that men have always done.

Bernays popularized the idea of bacon for breakfast.

Not one to turn down a challenge, he set up the liaison between the tobacco industry and the American Medical Association that lasted for nearly 50 years. They proved to all and sundry that cigarettes were beneficial to health. Just look at ads in old issues of Life, Look, Time or Journal of the American Medical Association from the 40s and 50s in which doctors are recommending this or that brand of cigarettes as promoting healthful digestion, or whatever.

He also invented the slogan Safety First, creating an industry which was founded on our obsession with the illusion of safety

During the next several decades Bernays and his colleagues evolved the principles by which masses of people could be generally swayed through messages repeated over and over, hundreds of times per week.

Once the economic power of media became apparent, other countries of the world rushed to follow our lead. But Bernays remained the gold standard. He was the source to whom the new PR leaders across the world would always defer. Even Josef Goebbels, Hitler’s minister of propaganda, author of the Final Solution, was an avid student of Edward Bernays. Using Bernays principles, Goebbels developed the popular rationale he would use to convince the Germans that the Final Solution was the only option to purify their race. (Stauber)

This is the reach of Bernays.

SMOKE AND MIRRORS

As he saw it, Bernays’ job was to reframe an issue; to create a desired image that would put a particular product or concept in a desirable context. He never saw himself as a master hoodwinker, but rather as a beneficent servant of humanity, providing a valuable service. Bernays described the public as a ‘herd that needed to be led.’ And this herdlike thinking makes people “susceptible to leadership.” Bernays never deviated from his fundamental axiom to “control the masses without their knowing it.” The best PR happens with the people unaware that they are being manipulated.

Stauber describes Bernays’ rationale like this:

“the scientific manipulation of public opinion was necessary to overcome chaos and conflict in a democratic society.” — Trust Us, p 42

These early mass persuaders postured as performing a moral service for humanity in general. Democracy was too good for people; they needed to be told what to think, because they were incapable of rational thought by themselves. Here’s a paragraph from Bernays’ Propaganda:

“Those who manipulate the unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested largely by men we have never heard of. This is a logical result of the way in which our democratic society is organized. Vast numbers of human beings must cooperate in this manner if they are to live together as a smoothly functioning society. In almost every act of our lives whether in the sphere of politics or business in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires that control the public mind.”

A tad different from Thomas Jefferson’s view on the subject:

“I know of no safe depository of the ultimate power of the society but the people themselves; and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise that control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not take it from them, but to inform their discretion.”

Inform their discretion. Bernays believed that only a few possessed the necessary insight into the Big Picture to be entrusted with this sacred task. And luckily, he saw himself as one of that elect.

Josef Goebbels, an avid student of Bernays, in turn had another apt pupil of his own: Adolf Hitler:

“What good fortune for those in power that the people do not think… It gives us a very special, secret pleasure to see how unaware the people around us are of what is really happening to them…Through clever and constant application of propaganda, people can be made to see paradise as hell, and also the other way around, to consider the most wretched sort of life as paradise.”

HERE COMES THE MONEY

Once the possibilities of applying Freudian psychology to mass media were glimpsed, Bernays soon had more corporate clients than he could handle. Global corporations fell all over themselves courting the new Image Makers. There were dozens of goods and services and ideas to be sold to a susceptible public. Over the years, these players have had the money to make their images happen. A few examples:

THE PLAYERS

Dozens of PR firms have emerged to answer the demand for spin control. Among them:

-

Mongovin, Biscoe, and Duchin

Though world-famous within the PR industry, these are names we don’t know, and for good reason. The best PR goes unnoticed. They are invisible. For decades they have created the opinions that most of us were raised with, on virtually any issue which has the remotest commercial value, including:

-

fluoridation of city water

-

household cleaning products

-

cancer research and treatment

-

images of celebrities, including damage control

-

crisis and disaster management

-

genetically modified foods

-

food additives; processed foods

LESSON #1

Bernays learned early on that the most effective way to create credibility for a product or an image was by “independent third-party” endorsement. For example, if General Motors were to come out and say that global warming is a hoax thought up by some liberal tree-huggers, people would suspect GM’s motives, since GM’s fortune is made by selling automobiles. If however some independent research institute with a very credible sounding name like the Global Climate Coalition comes out with a scientific report that says global warming is really a fiction, people begin to get confused and to have doubts about the original issue.

So that’s exactly what Bernays did. With a policy inspired by genius, he set up “more institutes and foundations than Rockefeller and Carnegie combined.” (Stauber p 45) Quietly financed by the industries whose products were being evaluated, these “independent” research agencies would churn out “scientific” studies and press materials that could create any image their handlers wanted. Such front groups are given high-sounding names like:

-

Temperature Research Foundation

-

International Food Information Council

-

The Advancement of Sound Science Coalition

-

Industrial Health Federation

-

International Food Information Council

-

Center for Produce Quality

-

Tobacco Institute Research Council

-

American Council on Science and Health

Alliance for Better Foods

Sound pretty legit, don’t they? All are bought and paid for.

As Stauber explains, these organizations and hundreds of others like them are front groups whose sole mission is to advance the image of the global corporations who fund them, like those listed above. This is accomplished in part by an endless stream of ‘press releases’ announcing “breakthrough” research to every radio station and newspaper in the country. (Robbins) Many of these canned reports read like straight news, and indeed are purposely molded in the news format. This saves journalists the trouble of researching the subjects on their own, especially on topics about which they know very little. Entire sections of the release or in the case of video news releases, the whole thing can be just lifted intact, with no editing, given the byline of the reporter or newspaper or TV station – and voilà! Instant news – copy and paste. Written by corporate PR firms.

Does this really happen? Every single day, since the 1920s when the idea of theNews Release was first invented by Ivy Lee. (Stauber, p 22) Sometimes as many as half the stories appearing in an issue of the Wall St. Journal are based solely on such PR press releases… (22) These types of stories are mixed right in with legitimately researched stories. Unless you have done the research yourself, you won’t be able to tell the difference. So when we see new “research” being cited, we should always first suspect that the source is another industry-backed front group. A common tip-off is the word “breakthrough.”

THE LANGUAGE OF SPIN

As 1920s spin pioneers like Ivy Lee and Edward Bernays gained more experience, they began to formulate rules and guidelines for creating public opinion. They learned quickly that mob psychology must focus on emotion, not facts. Since the mob is incapable of rational thought, motivation must be based not on logic but on presentation. Here are some of the axioms of the new science of PR:

-

technology is a religion unto itself

-

if people are incapable of rational thought, real democracy is dangerous

-

important decisions should be left to experts

-

never get too technical; but keep repeating the word “science”

-

when reframing issues, stay away from substance; create images

never state a clearly demonstrable lie

Words are very carefully chosen for their emotional impact. Here’s an example. A front group called the International Food Information Council handles the public’s natural aversion to genetically modified foods. Trigger words are repeated all through the text. Now in the case of GM foods, the public is instinctively afraid of these experimental new creations which have suddenly popped up on our grocery shelves since the ;ate 90s and which are said to alter our DNA. The IFIC wants to reassure the public of the safety of GM foods. So it avoids words like:

Instead, good PR for GM foods contains words like:

It’s just basic Freud/Tony Robbins/NLP word association. The fact that GM foods are not hybrids that have been subjected to the slow and careful scientific methods of real cross-breeding doesn’t really matter. This is pseudoscience, not science. Form is everything and substance just a passing myth. (Trevanian)

Who do you think funds the International Food Information Council? Take a wild guess. Right – Monsanto, DuPont, Frito-Lay, Coca Cola, Nutrasweet – those in a position to make fortunes from GM foods. (Stauber p 20)

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD PROPAGANDA

As the science of mass control evolved, PR firms developed further guidelines for effective copy. Here are some of the gems:

dehumanize the attacked party by labeling and name calling

speak in glittering generalities using emotionally positive words

when covering something up, don’t use plain English; stall for time; distract

get endorsements from celebrities, churches, sports figures, street people – anyone who has no expertise

in the subject

the ‘plain folks’ ruse: us billionaires are just like you

when minimizing outrage, don’t say anything memorable – platitudes are best

when minimizing outrage, point out the benefits of what just happened

when minimizing outrage, avoid moral issues

Keep this list. Start watching for these techniques. Not hard to find – look at today’s paper or tonight’s TV news. See what they’re doing; these guys are good!

SCIENCE FOR HIRE

PR firms have become very sophisticated in the preparation of news releases. They have learned how to attach the names of famous scientists to research that those scientists have not even looked at. (Stauber, p 201) It’s a common practice. In this way, the editors of newspapers and TV news shows are themselves often unaware that an individual release is a total PR fabrication. Or at least they have “deniability,” right?

Stauber tells the amazing story of how leaded gas came into the picture. In 1922, General Motors discovered that adding lead to gasoline gave cars more horsepower. When there was some concern about safety, GM paid the Bureau of Mines to do some fake “testing” and publish spurious research that ‘proved’ that inhalation of lead was harmless. Enter Charles Kettering.

Founder of the world famous Sloan-Kettering Memorial Institute for medical research, Charles Kettering also happened to be an executive with General Motors. By some strange coincidence, we soon have Sloan-Kettering issuing reports stating that lead occurs naturally in the body and that the body has a way of eliminating low level exposure. Through its association with The Industrial Hygiene Foundation and PR giant Hill & Knowlton, Sloane-Kettering opposed all anti-lead research for years. (Stauber p 92). Without organized scientific opposition, for the next 60 years more and more gasoline became leaded, until by the 1970s, 90% or our gasoline was leaded.

Finally it became too obvious to hide that lead was a major carcinogen, which they knew all along, and leaded gas was phased out in the late 1980s. But during those 60 years, it is estimated that some 30 million tons of lead were released in vapor form onto American streets and highways. 30 million tons. (Stauber)

That is PR, my friends.

JUNK SCIENCE

In 1993 a guy named Peter Huber wrote a new book and coined a new term. The book was Galileo’s Revenge and the term was junk science. Huber’s shallow thesis was that real science supports technology, industry, and progress. Anything else was suddenly junk science. Not surprisingly, Stauber explains how Huber’s book was supported by the industry-backed Manhattan Institute.

Huber’s book was generally dismissed not only because it was so poorly written, but because it failed to realize one fact: true scientific research begins with no conclusions. Real scientists are seeking the truth because they do not yet know what the truth is.

True scientific method goes like this:

1. form a hypothesis

2. make predictions for that hypothesis

3. test the predictions

4. reject or revise the hypothesis using the test results

5. describe the limitations of the present position

6. always ask the next question

Boston University scientist Dr. David Ozonoff explains that ideas in science are themselves like “living organisms, that must be nourished, supported, and cultivated with resources for making them grow and flourish.” (Stauber p 205) Great ideas that don’t get this financial support because the commercial angles are not immediately obvious – these ideas wither and die.

Another way you can often distinguish real science from phony is that real science points out flaws in its own research. Phony science pretends there were no flaws.

THE REAL JUNK SCIENCE

Contrast this with modern PR and its constant pretensions to sound science. Corporate sponsored research, whether it’s in the area of drugs, GM foods, or chemistry begins with predetermined conclusions. It is the job of the scientists then to prove that these conclusions are true, because of the economic upside that proof will bring to the industries paying for that research. This invidious approach to science has shifted the entire focus of research in America during the past 50 years, as any true scientist is likely to admit. If a drug company is spending 10 million dollars on a research project to prove the viability of some new drug, and the preliminary results start coming back about the dangers of that drug, what happens? Right. No more funding. The well dries up. What is being promoted under such a system? Science? Or rather Entrenched Medical Error?

Stauber documents the increasing amount of corporate sponsorship of university research. (206) This has nothing to do with the pursuit of knowledge. Scientists lament that research has become just another commodity, something bought and sold. (Crossen)

THE TWO MAIN TARGETS OF “SOUND SCIENCE”

It is shocking when Stauber shows how the vast majority of corporate PR today opposes any research that seeks to protect public health and the environment

It’s a funny thing that most of the time when we see the phrase “junk science,” it is in a context of defending something that threatens either the environment or our health. This makes sense when one realizes that money changes hands only by selling the illusion of health and the illusion of environmental protection or the illusion of health. True public health and real preservation of the earth’s environment have very low market value.

Stauber thinks it ironic that industry’s self-proclaimed debunkers of junk science are usually non-scientists themselves. (255) Here again they can do this because the issue is not science, but the creation of images.

THE LANGUAGE OF ATTACK

When PR firms attack legitimate environmental groups and alternative medicine people, they again use special words which will carry an emotional punch:

Our riflemen are sharpshooters – theirs are snipers.

The next time you are reading a newspaper article about an environmental or health issue, note how the author shows bias by using the above terms. This is the result of very specialized training. It is a very disciplined art and science.

Another standard PR tactic is to use the rhetoric of the environmentalists themselves to defend a dangerous and untested product that poses an actual threat to the environment. This we see constantly in the PR smokescreen that surrounds genetically modified foods. They talk about how GM foods are necessary to grow more food and to end world hunger, when the reality is that GM foods actually have lower yields per acre than natural crops. (Stauber p 173) The grand design sort of comes into focus once you realize that almost all GM foods have been created by the sellers of herbicides and pesticides so that those plants can withstand greater amounts of herbicides and pesticides. (see The Magic Bean)

THE MIRAGE OF PEER REVIEW

Publish or perish is the classic dilemma of every research scientist. That means whoever expects funding for the next research project had better get the current research paper published in the best scientific journals. And we all know that the best scientific journals, like JAMA, New England Journal, British Medical Journal, etc. are peer-reviewed. Peer review means that any articles which actually get published, between all those full color drug ads and pharmaceutical centerfolds, have been reviewed and accepted by some really smart guys with a lot of credentials. The assumption is, if the article made it past peer review, the data and the conclusions of the research study have been thoroughly checked out and bear some resemblance to physical reality.

But there are a few problems with this hot little set up. First off, money.

Even though prestigious venerable medical journals pretend to be so objective and scientific and incorruptible, the reality is that they face the same type of being called to account that all glossy magazines must confront: don’t antagonize your advertisers. Those full-page drug ads in the best journals cost millions, Jack. How long will a pharmaceutical company pay for ad space in a magazine that prints some very sound scientific research paper that attacks the safety of the drug in the centerfold? Think about it. The editors may lack moral fibre, but they aren’t stupid.

Another problem is the conflict of interest thing. There’s a formal requirement for all medical journals that any financial ties between an author and a product manufacturer be disclosed in the article. In practice, it never happens. A study done in 1997 of 142 medical journals did not find even one such disclosure. (Wall St. Journal, 2 Feb 99)

A 1998 study from the New England Journal of Medicine found that 96% of peer reviewed articles had financial ties to the drug they were studying. (Stelfox, 1998) Big shock, huh? Any disclosures? Yeah, right. This study should be pointed out whenever somebody starts getting too pompous about the objectivity of peer review, like they often do.

Then there’s the outright purchase of space. A drug company may simply pay $100,000 to a journal to have a favorable article printed. (Stauber, p 204)

Fraud in peer review journals is nothing new. In 1987, the New England Journal ran an article that followed the research of R. Slutsky MD over a seven year period. During that time, Dr. Slutsky had published 137 articles in a number of peer-reviewed journals. NEJM found that in at least 60 of these 137, there was evidence of major scientific fraud and misrepresentation, including:

-

reporting data for experiments that were never done

-

reporting measurements that were never made

reporting statistical analyses that were never done (Engler)

Dean Black PhD, describes what he the calls the Babel Effect that results when this very common and frequently undetected scientific fraud in peer-reviewed journals is quoted by other researchers, who are in turn re-quoted by still others, and so on.

Want to see something that sort of re-frames this whole discussion? Check out the McDonald’s ads which routinely appear in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Then keep in mind that this is the same publication that for almost 50 years ran cigarette ads proclaiming the health benefits of tobacco. (Robbins)

Very scientific, oh yes.

KILL YOUR TV?

Hope this chapter has given you a hint to start reading newspaper and magazine articles a little differently, and perhaps start watching TV news shows with a slightly different attitude than you had before. Always ask, what are they selling here, and who’s selling it? And if you actually follow up on Stauber & Rampton’s book and check out some of the other resources below, you might even glimpse the possibility of advancing your life one quantum simply by ceasing to subject your brain to mass media. That’s right – no more newspapers, no more TV news, no more Time magazine or People magazine Newsweek.

You could actually do that. Just think what you could do with the extra time alone.

Really feel like you need to “relax” or find out “what’s going on in the world” for a few hours every day? Think about the news of the past couple of years for a minute. Do you really suppose the major stories that have dominated headlines and TV news have been “what is going on in the world?” Do you actually think there’s been nothing going on besides the contrived tech slump, the contrived power shortages, the re-filtered accounts of foreign violence and disaster, even the new accounts of US retribution in the Middle East, making Afghanistan safe for democracy, bending Saddam to our will, etc., and all the other non-stories that the puppeteers dangle before us every day? What about when they get a big one, like with OJ or Monica Lewinsky or the Oklahoma city bombing? Or now with the Neo-Nazi aftermath of 9/11. Or the contrived war against Iraq? Do we really need to know all that detail, day after day? Do we have any way of verifying all that detail, even if we wanted to? What is the purpose of news? To inform the public? Hardly.

The sole purpose of news is to keep the public in a state of fear and uncertainty so that they’ll watch again tomorrow to see how much worse things got and to be subjected to the same advertising.

Oversimplification? Of course. That’s the hallmark of mass media mastery – simplicity. The invisible hand. Like Edward Bernays said, the people must be controlled without them knowing it.

Consider this: what was really going on in the world all that time they were distracting us with all that stupid vexatious daily smokescreen? We have no way of knowing. And most of it doesn’t even concern us even if we could know it. Fear and uncertainty — that’s what keeps people coming back for more.

If this seems like a radical outlook, let’s take it one step further:

What would you lose from your life if you stopped watching TV and stopped reading newspapers and glossy magazines altogether?

Whoa!

Would your life really suffer any financial, moral, intellectual, spiritual, or academic loss from such a decision?

Do you really need to have your family continually absorbing the illiterate, amoral, phony, culturally bereft, desperately brainless values of the people featured in the average nightly TV program? Are these fake, programmed robots “normal”?

Do you need to have your life values constantly spoon fed to you?

Are those shows really amusing, or just a necessary distraction to keep you from looking at reality, or trying to figure things out yourself by doing a little independent reading? Or perhaps from having a life?

Name one example of how your life is improved by watching TV news and reading the evening paper or the glossy magazines. What measurable gain is there for you?

What else could we be doing with all this freed-up time that would actually expand awareness?

PLANET OF THE APES?

There’s no question that as a nation, we’re getting dumber year by year. Look at the presidents we’ve been choosing lately. Ever notice the blatant grammar mistakes so ubiquitous in today’s advertising and billboards? Literacy is marginal in most American secondary schools. Three-fourths of California high school seniors can’t read well enough to pass their exit exams. (SJ Mercury 20 Jul 01) If you think other parts of the country are smarter, try this one: hand any high school senior a book by Dumas or Jane Austen, and ask them to open to any random page and just read one paragraph out loud. Go ahead, do it. SAT scales are arbitrarily shifted lower and lower to disguise how dumb kids are getting year by year. ADD: A Designer Disease At least 10% have documented “learning disabilities,” which are reinforced and rewarded by special treatment and special drugs. Ever hear of anyone failing a grade any more?

Or observe the intellectual level of the average movie which these days may only last one or two weeks in the theatres, especially if it has insufficient explosions, chase scenes, silicone, fake martial arts, and cretinesque dialogue. Doesn’t anyone else notice how badly these 30 or 40 “movie stars” we keep seeing over and over in the same few plots must now overact to get their point across to an ever-dimming audience?

Radio? Consider the low mental qualifications of the falsely animated corporate simians they hire as DJs — seems like they’re only allowed to have 50 thoughts, which they just repeat at random. And at what point did popular music cease to require the study of any musical instrument or theory whatsoever, not to mention lyric? Perhaps we just don’t understand this emerging art form, right? The Darwinism of MTV – apes descended from man.

Ever notice how most articles in any of the glossy magazines sound like they were all written by the same guy? And this writer just graduated from junior college? And yet he has all the correct opinions on social issues, no original ideas, and that shallow, smug, homogenized corporate omniscience, which enables him to assure us that everything is fine…

All this is great news for the PR industry – makes their job that much easier. Not only are very few paying attention to the process of conditioning; fewer are capable of understanding it even if somebody explained it to them.

TEA IN THE CAFETERIA

Let’s say you’re in a crowded cafeteria, and you buy a cup of tea. And as you’re about to sit down you see your friend way across the room. So you put the tea down and walk across the room and talk to your friend for a few minutes. Now, coming back to your tea, are you just going to pick it up and drink it? Remember, this is a crowded place and you’ve just left your tea unattended for several minutes. You’ve given anybody in that room access to your tea.

Why should your mind be any different? Turning on the TV, or uncritically absorbing mass publications every day – these activities allow access to our minds by “just anyone” – anyone who has an agenda, anyone with the resources to create a public image via popular media. As we’ve seen above, just because we read something or see something on TV doesn’t mean it’s true or worth knowing. So the idea here is, like the tea, perhaps the mind is also worth guarding, worth limiting access to it.

This is the only life we get. Time is our total capital. Why waste it allowing our potential, our scope of awareness, our personality, our values to be shaped, crafted, and boxed up according to the whims of the mass panderers? There are many important issues that are crucial to our physical, mental, and spiritual well-being which require time and study. If it’s an issue where money is involved, objective data won’t be so easy to obtain. Remember, if everybody knows something, that image has been bought and paid for.

Real knowledge takes a little effort, a little excavation down at least one level below what “everybody knows.”

Copyright MMXV – Dr Tim O’Shea

References

Stauber & Rampton – Trust Us, We’re Experts – Tarcher/Putnam 2001

Ewen, Stuart – PR!: A Social History of Spin – Basic Books 1996

Tye, Larry – The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays and the Birth of Public Relations – Crown Publishers, Inc. 2001

Bernays, E – Propaganda – Liveright 1928

King, R – Medical journals rarely disclose researchers’ ties – Wall St. Journal, February 2, 1999

Engler, R et al. – Misrepresentation and Responsibility in Medical Research – New England Journal of Medicine v 317 p 1383, November 26, 1987

Black, D, PhD – Health At the Crossroads – Tapestry 1988

Trevanian – Shibumi, 1983

Crossen, C – Tainted Truth: The Manipulation of Fact in America, 1996

Robbins, J – Reclaiming Our Health – Kramer 1996

Huxley, A – The Doors of Perception: Heaven and Hell – Harper and Row 1954

O’Shea, T – Genetically Modified Foods: A Short Introduction