Saturday Matinee: Car Cemetery

By Stu Willis

Source: Sex Gore Mutants

In an unspecified place, in an unspecified post-war future, the world is divided into two factions: the brutal Government-sponsored police regime, and the punks they hope to quash.

The punks spend their days scavenging the barren, post-Apocalyptic wastelands. Their nights are spent searching for “cemeteries” – secret places where they can hide from the authorities and enjoy a taste of their former lives. Much of the action is set in the titular car cemetery, a junkyard fashioned to house people in, fortress-style. Imagine a cross between STREET TRASH’s scrap-yard and Barter Town from MAD MAX BEYOND THUNDERDOME.

The cemetery’s pig-like keeper Milos (Roland Amstutz) welcomes the latest bunch of motley punks into his haven, referring to it as “Babylon”. Through his loudhailer he tells his guests that while they are there they are free to indulge in whatever perversions tickle their fancy. That includes the services of his own prostitute girlfriend, Dila (Juliet Berto).

The young adults retire to their individual car wrecks and get busy with all manner of sexual kinks, which allows director Fernando Arrabal to wallow in some customary carnal images before honing in on 80s fashion victim Tope (Boris Bergman) and his loyal friend.

They, along with everyone else, have heard that a Messiah-like rocker by the name of Emanou (Alain Bashung) is rumoured to be headed for the cemetery. There is a buzz in the air concerning his expected arrival but Tope, who has crossed paths with the new-age Christ figure once before, intimates designs on betraying him.

When Milos demands money from his transient guests for supper, they revolt. Fortunately for all, a riot is avoided by the arrival of the enigmatic Emanou. He is able to take two Big Mac sandwiches and feed the entire flock with them.

Meanwhile, as Emanou’s story is told in flashback by awestruck onlookers and Tope plots against the sultry music man, the cops await orders from their mysterious ruler The Bunker to locate and kill the Messiah.

Ah, I get it! Dila is the whore of Babylon … the cops are the Romans … Emanou walks on water and feeds the, well, around 20-or-so extras. Yes, Arrabal is reworking tales from the Bible through the filters of post-Apocalyptic sci-fi and new wave music.

Arrabal became a prominent figure in the Panic Movement of the 1960s, penning the play FANDO AND LIS – the screen adaptation of which later became the feature film debut of Alexandro Jodorowsky (SANTA SANGRE; EL TOPO). The Spanish surrealist then went on to become a cult filmmaker of his own distinction in the 1970s, with the brilliant VIVA LA MUERTE, the even wilder I WILL WALK LIKE A CRAZY HORSE and his nihilistic epic THE GUERNICA TREE (all three of which can be found in Cult Epics’ superb THE FERNANDO ARRABAL COLLECTION VOLUME 1 box-set).

CAR CEMETERY then, from 1983, comes as something of a disappointment. It’s not overly bad, just not as out-there or creative as its predecessors. The religious allegories have always been rife in Arrabal’s work, but here the blasphemy seems only half-hearted. The anger appears to have dissipated along with the budget for this low-rent REPO MAN relation.

The cast are game. Bashung, a famous singer in his native France up until his death from lung cancer in 2009, has an undeniable presence: he succeeds in the effortless cool of many a rock star. Everyone around him seems overly animated, as if being directed by Andrej Zulawski. But, somehow, it helps to keep the odd atmospherics afloat.

The problem is that the script is horribly ripe. Borrowing liberally from the Bible, this is portentous claptrap even by Arrabal’s standards (I say that with all due respect: I am a fan of the man). It’s true to say that his previous films were stuffed to the brim with surreal religious motifs and visual correlations between sex and death. Nothing has changed here, but everything feels so sedate in comparison. It’s no surprise to learn that this film is based on Arrabal’s play of the same name – and that explains its clunkiness: the limited sets; the dreadfully wooden dialogue; the cheap arthouse pretensions.

Worse still, the whole thing is given a punk rock look that firmly dates the film in the early 1980s – and not in a good way. It’s like Peter Greenaway directing CAFE FLESH with no budget, or the cast of JUBILEE racing through a softcore sci-fi variant of JESUS OF MONTREAL.

Cult Epics’ disc presents the film uncut in anamorphic 1.66:1. The transfer is generally dark and colours look a tad faded. Having said that, this is an obscure and largely unseen film – it’s amazing just to see it on DVD. It’s perfectly watchable, and relatively clean to boot.

The French audio track offered is 2.0 and is a good proposition throughout. Optional English subtitles are easy to read and, for the most part, free from typing errors.

A static main menu page leads into a static scene-selection menu allowing access to CAR CEMETERY via 10 chapters.

The only extras on the disc are trailers for VIVA LA MUERTE, I WILL WALK LIKE A CRAZY HORSE and THE GUERNICA TREE. The first and last of these are equipped with English subtitles, while the HORSE trailer has no dialogue.

The disc is a basic one, but fair when you consider that it’s likely to be the only legitimate standalone release this film is likely to receive. Cult Epics have also released CAR CEMETERY as part of a three-disc box-set – THE FERNANDO ARRABAL COLLECTION VOLUME 2 – which also contains the whimsical family film THE EMPEROR OF PERU (with Mickey Rooney!) and a third disc of documentaries, including the recommended watch FAREWELL BABYLON.

CAR CEMETERY is a hideously dated 80s film that fails to escape from the pratfalls of its stage origins. The fashions, the sets, the allegories – its all rank. But there is something that makes it just-to-say work regardless, be it the occasional inspired image (Dila conversing with a miniature angel; Tope’s fate) or authentic squalor and subversive anti-establishment message that seeps through. Arrabal is a cinematic terrorist of considerable intelligence and even a lesser film such as this demonstrates as much. Just don’t go into it expecting the same levels of polemical art or extremism of his earlier films.

Watch Car Cemetery on Kanopy here: https://www.kanopy.com/en/kcls/video/10605045

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: In Search of Mœbius

In Search of Mœbius: A Documentary Introduction to the Inscrutable Imagination of the Late Comic Artist Mœbius

By Colin Marshall

Source: Open Culture

“I’ll die in some truly banal manner, the way I live,” says the subject of BBC Four’s In Search of Mœbius. I don’t know what would constitute a non-banal manner of death — or, for that matter, a banal one — but nobody familiar with modern comic art could believe that Jean Giraud, also known as Mœbius, could possibly have lived a banal life. If you haven’t read a comic since your childhood Sunday funnies, you need only watch this program to understand why the artist’s passing on Saturday brought forth so many breathless tributes. You’ll also catch a glimpse of the vast possibilities offered by comic art as a form. The inscrutable workings of Mœbius’ peculiar imagination drove him far into this territory, and many creators (in comics and elsewhere) still struggle to follow him.

Aside from Mœbius himself, the program interviews the coterie from his early years in France at Métal Hurlant, the magazine that would open the space for his distinctively subconscious-fueled, near-psychedelic yet richly textural science-fiction sensibility. It goes on to talk with well-known admirers who, feeling the resonance of those particular (and particularly difficult to describe) qualities of Mœbius’ vision that cross so many national and artistic boundaries, found ways to work with him.

These high-profile collaborators range from Marvel Comics founder Stan Lee, who enlisted Mœbius to take Silver Surfer in new aesthetic and intellectual directions, to screenwriter Dan O’Bannon, biomechanical surrealist H.R. Giger, and filmmaker/mystic Alejandro Jodorowsky, who worked with him on an unrealized (but still tantalizing) film adaptation of Dune.

In Search of Mœbius also explores the real landscapes that must have worked their way into Mœbius’ imagination, contributing to the strikingly unreal landscapes that worked their way out of it. We see the deserts of Mexico, traces of which appear in his Western series Blueberry, where he visited his mother in the 1950s. We see the Los Angeles he considered “really an amazing city,” where his work on Silver Surfer took him. We even see him in his native land, standing before the harshly iconic Bibliothèque nationale de France. Mœbius may be gone, but the world inside his head remains forever open for us on the page to explore. H/T @EscapeIntoLife

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.

Two for Tuesday

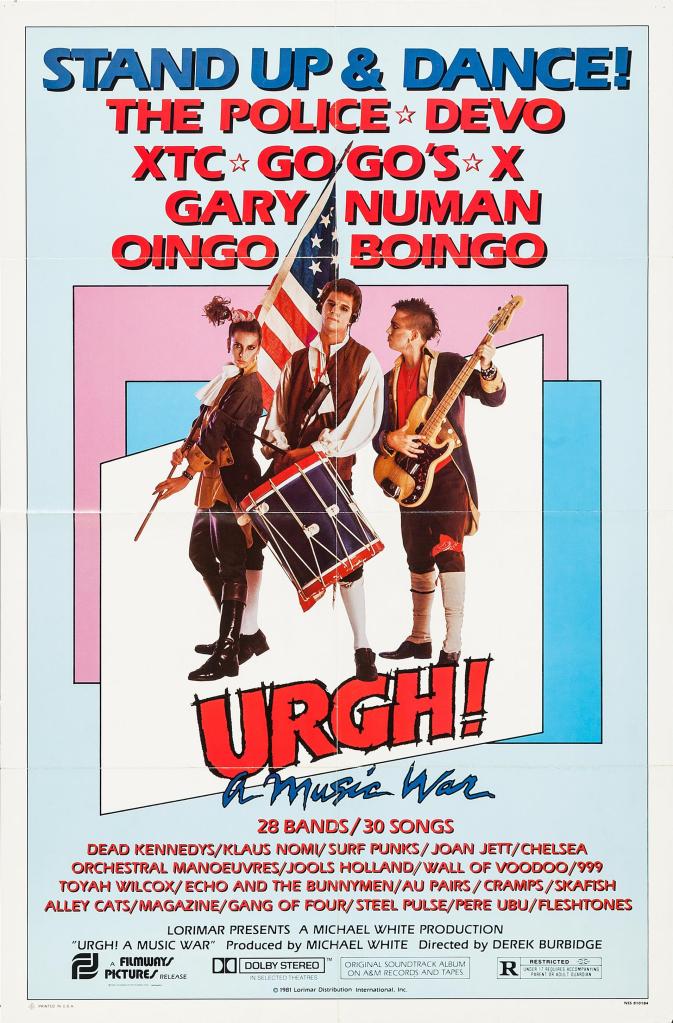

Saturday Matinee: Urgh! A Music War

By Rob Gonsalves

Source: Rob’s Movie Vault

I loved every second of Urgh! A Music War, even when I was baffled. Perhaps especially when I was baffled. How else does one respond to such only-in-the-early-’80s acts as Invisible Sex, who appear onstage in makeshift hazmat suits, or the late Klaus Nomi with his futuro-bizarro getup and his soaring falsetto, or the Surf Punks with their punk-nerd outfits and the simulated sex in an onstage beach shack? Dear God, what a strange and wondrous time for alternative music. This was an era in which the Go-Gos could be sandwiched between the roughhouse punk acts Athletico Spizz 80 and Dead Kennedys and somehow not seem out of place. (Belinda Carlisle, in the Urgh! footage, may be bouncy and happy, but she’s got the prerequisite short punk ‘do.)

Urgh! was filmed in 1980 at a variety of locations (New York, London, France, Los Angeles) as a somewhat scattershot attempt to capture some of the emerging New Wave and punk acts of the day. It can be seen today as an accidental Woodstock, as musically important in its way as Michael Wadleigh’s Oscar-winning documentary was. It catches, for instance, one of XTC’s last live performances (a ripsnorting “Respectable Street,” easily one of the film’s highlights) before Andy Partridge got allergic to the stage life and announced that XTC would no longer do concerts. At the end, when the Police do “Roxanne” (a great performance — man, they kicked ass in concert back in the day) and then “So Lonely,” they invite various groups we’ve seen in the movie: UB40, Skafish, the ivory-tickling Jools Holland, and others; it’s a semi-historic jam.

When the camera moves in on one attractive woman or another in the crowd (which is somewhat often), you can tell that at the time the camera crew was just filming whatever caught their eye (and pants), but seen today it’s a cultural document: It’s fun to see how young women were dressing to go see X or Pere Ubu. From this movie, you might also conclude that the Lollapalooza generation didn’t invent pogo-ing, moshing, and stage-diving; you see it all here (most amusingly, I thought, during sets by the Go-Gos and Oingo Boingo). Urgh! also captures a deadpan-antagonistic time in rock. Many of the punk and New Wave acts here don’t seem to give a fuck whether you like them or not, yet they come to play and they play hard. When Lux Interior of the Cramps sticks his mike in his mouth and staggers around grunting as it hangs out, it’s a primal moment to rival Pete Townshend’s guitar-smashing; it comes from the same basic impulse, anyway.

You notice, too, the high level of joy in these performances. Many of the arrogant young (mostly) men onstage may have been in it to entertain themselves, but they keep things moving. The gyrations here couldn’t be further from the frozen-faced growling of today’s “alternative” rock. Dead Kennedys’ frontman Jello Biafra, spitting out “Bleed for Me,” exhorts the crowd to enjoy the freedom to hear punk rock — while it lasts (the punk rock and the freedom). Biafra has a corrosive staccato gaiety that matches Johnny Rotten at his most splenetic. Kenneth Spiers, lead shouter of Athletico Spizz 80 (doing their novelty hit “Where’s Captain Kirk?”), jumps around spraying the audience, fellow band members, and himself with silly string, then tosses the empty can over his shoulder, not caring if it hits any of his bandmates. Jim Skafish bends himself into art-rock pretzels during “Sign of the Cross,” a nerd’s idea of punk (a lot of the music here is a nerd’s idea of punk, including Devo, represented here with the relentless “Uncontrollable Urge”). Steel Pulse illustrate their song “Ku Klux Klan” with a (black) band member capering onstage in a KKK outfit. Howard Devoto of Magazine — the former Buzzcocks member who bears an uncanny resemblance to Chuck & Buck‘s Mike White — strolls around the stage as if waiting for a bus, a sly inversion of punk flailing that has its own quiet punk wit. In comparison with the carefree showmanship seen in Urgh!, many of today’s acts seem stoic, almost monastic, and far more self-involved and nihilistic than the most insular New Wave warbler.

Half of these groups didn’t seem to go anywhere after 1981, but it’s a treat to go back in time and catch the ones that did make it. Two elder statesmen of film-soundtrack composition, Mark Mothersbaugh of Devo and Danny Elfman of Oingo Boingo, come off here like the sweaty madmen they were back then. Joan Jett (doing an electrifying “Bad Reputation”) looks appealingly almost-chubby, before the label presumably told her to slim down for MTV; the same is true of Belinda Carlisle. Exene Cervenka nonchalantly commands the stage on X’s “Beyond and Back,” as does Gary Numan (tooling around in a little car) on “Down in the Park.” The one-hit wonders and no-hit wonders are equally alluring. I was charmed by Toyah Willcox’s jubilant hopping about, trying to be cool but too happy to pull it off. It’s a shame the exuberant Chelsea weren’t better known. Wall of Voodoo, whose lead singer Stan Ridgway resembles a crank-addled Griffin Dunne, pumps up the defiant “Back in Flesh” (no, not “Mexican Radio” — that would be too obvious). The movie is heavily male, but the female singers — Willcox, Carlisle, Jett — distinguish themselves by their clarity. Joan Jett screams as fiercely as anyone, but you can understand everything she’s saying, whereas many of the male singers rant unintelligibly (which can be its own kind of hostile fuck-you lyricism). The viewer/listener comes away thinking that Jett and the other women have fought too hard to be on that stage to waste the opportunity to be heard; the men, accustomed to being heard, let their words clatter and fall every which way.

Jonathan Demme is thanked in the credits, and much of Urgh! shares the concert-film aesthetic he pioneered in Stop Making Sense and continued in Storefront Hitchcock. Director Derek Burbidge, who made rock videos back then (including “Cars” for Gary Numan and pretty much all the Police’s early MTV highlights), is into simplicity, not flash (a useful approach when catching thirty-odd bands on the fly in three different countries). The bands are given space to work up their own rhythm — the editing doesn’t do it for them. Burbidge is as fond of the mammoth close-up as Sergio Leone ever was, and half of “Roxanne” seems to explore Sting’s nostrils from previously unseen angles. Performers like Lux Interior and Jello Biafra seem to be dripping sweat right onto you. The effect is to take you into the front row.

Urgh! doesn’t (and can’t possibly) have the cohesive brilliance or musical momentum of Stop Making Sense — the styles are simply too varied, throwing you from catatonic New Wave to thrashing punk in an eyeblink. Still, as a record of a moment and a sound, it ranks up there with the best you’ve seen and heard.

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

Why Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind Remains Unforgettable

By Matt Zoller Seitz

Source: RogerEbert.com

Despite its gently bummed-out vibe, “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” is a sneakily powerful film. It’s so affecting, in fact, that I get a little sad just thinking about the story and characters. Even though I saw “Eternal Sunshine” twice in a theater when it came out and put it on my 2004 Top 10 list, I only revisited it once more after that (to be interviewed for a video essay that, as far as I know, is no longer available online) and haven’t watched it since. It’s not just the story itself that’s piercing; it’s the film’s visualization of memories being destroyed, which hits harder now after seeing so many older friends and relatives (including my mother) succumb to Alzheimer’s disease. It’s a truly great film that can be endlessly appreciated and analyzed for what it’s actually about even while it acquires secondary meanings.

“Eternal Sunshine” is the most perfect film ever made from a Charlie Kaufman screenplay, although Kaufman’s self-written directorial debut “Synecdoche, New York” is an altogether greater, or at least more grandly ambitious, work. Michel Gondry’s decision to shoot almost the entire film in a handheld, quasi-documentary style and have all the special effects appear to have been accomplished in-camera (i.e. through trickery on the set itself, in the manner of a filmed stage production) even when they were digitally assisted doesn’t just sell the idea that everything in the story is “really happening” even when it’s a memory: it blurs the line between what’s real and what’s remembered, an integral aspect of Kaufman’s script that informs every line and scene. The “spotlight” effects created by swinging flashlights on dark streets and in unlit interiors are especially disturbing. When the characters run or hide in those sorts of compositions in sequences, the film boldfaces its otherwise subtly acknowledged identity as a science fiction movie. Past and present (and possible future) lovers Joel Barish (Jim Carrey) and Clementine Kruczynski (Kate Winslet) might as well be rebels in a Terminator film, scampering through bombed-out panoramas and trying not to get zapped by a machine.

Star Jim Carrey was no stranger to dramatic roles by that point in his career, having starred in the media satire “The Truman Show,” the Andy Kaufman biography “Man on the Moon,” and the 1950s-set romantic thriller “The Majestic” (by “The Shawshank Redemption” director Frank Darabont, largely forgotten but worth a look). But his performance as Joel Barish (rhymes with perish) stands apart from everything else he’s done because of its staunchly life-sized approach. It’s a performance as a regular guy that’s entirely free of movie star egocentrism, unflatteringly (or perhaps just unselfconsciously) depicted from start to finish. It’s not easy to forget all the classic Carrey slapstick gyrations that preceded it, and that made him one of the most bankable stars of the 1990s, but somehow you do. He even looks different in the face, somehow. If I’d gone into it not knowing it was him, I might’ve thought, “Who is that actor? He’s excellent, and he looks kinda like Jim Carrey.”

Kate Winslet, who became an international star with Peter Jackson’s “Heavenly Creatures” and a superstar with “Titanic,” established herself as a bona fide character actress in this film. She inhabited Clementine so completely that she unknowingly perfected a type: The Manic Pixie Dream Girl, as per Nathan Rabin’s wonderful phrase describing a woman who “exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures.” I don’t think that’s an entirely accurate description of Clementine as a person; with a bit of distance, she seems more like somebody with undiagnosed mental illness, and Joel is probably right there with her. But it does describe how the role echoed throughout time and through other films and TV shows (including “Elizabethtown,” the film Rabin was reviewing when he coined the phrase, and that happens to costar “Eternal Sunshine” cast-member Kirsten Dunst). There’s no denying the effect the performance had on future movies, which served up endless variations on Clementine.

Gondry’s style creates an analogy for what happens when a person’s memories begin to disintegrate or disappear, in the all-over, “global” sense (Alzheimer’s), as well as for the fleeting universal experience of struggling to remember a name, or some aspect of a dream, and somehow managing to grasp a sliver of it, only to see it slip away and vanish.

The movie also somehow captures that awful knowledge that the personal dramas which consume us go unnoticed by almost everyone else. When it came out, the movie felt so immediate that it was as if you were seeing something that was actually happening, out in the physical world. It still feels like something that could happen because of how it’s lit and filmed. The action seems to have been captured entirely in real locations even when the actors are on sets. The locations tend to be unglamorous, with the notable exception of the beach at Montauk where Joel and Clementine first met (there’s no way to make a beach seem anything less than majestic). The ordinary magic that constantly happens inside each of us – the staggeringly complicated interplay between present-tense observation and interactions; the stabbing intrusions of memory, fantasy, and trauma – contrasts against boringly regular urban and suburban settings that seem to have been chosen because they are the human equivalent of the featureless mazes where rodents of science reside. When Joel and Clementine race through memory spaces where Joel has hidden memories of Clementine to prevent their erasure, they scamper and stop, twist and change direction. They’re people in a mouse-maze.

There’s also a fascinating matter-of-factness to the way the film presents the interactions of Joel and Clementine and the (largely unseen) team of memory-erasers (headed by Tom Wilkinson, and including Dunst, Mark Ruffalo, and Elijah Wood; what a cast!), as well as the way the film un-peels the layers of casual corruption surrounding the process by which memories are destroyed. When you have access to a memory erasing machine and no legal or ethical oversight, the tech is bound to be abused. Is there even an ethical way to use it? Is it right to simply erase something traumatic from a person’s brain? Is it better than teaching the person how to process, understand, and transcend trauma?

There’s a scene at the end of 1981’s “Superman II” where Superman erases Lois Lane’s memory with a super-kiss to protect his secret identity as Clark Kent. The moment was viewed by most audiences at the time as a fairy tale flourish, along the lines of Superman turning back time to save Lois at the end of the first movie. Today it would be considered a non-consensual mental assault, like a roofie. “Eternal Sunshine” sometimes plays like a speculative drama about what would happen if it were possible to replicate Superman’s kiss and turn it into a service that people could pay for. No good could come from such a thing, which is a sure sign that some company out there is hard at work inventing it while its CEO chases billions in startup money from venture capitalists.

A crude version of the necessary technology has existed for decades. The indiscriminate electroshock therapy that was so common in mental hospitals in the middle part of the 20th century, and that often reduced patients to blankly smiling shells of their former selves, became more precisely targeted, to the point where the procedure is now considered an ordinary part of treatment. Ten years ago, scientists figured out by studying mice how to identify the places in the brain where traumatic or negative memories are kept, and “eradicate” them and/or associate them with pleasure. “In essence,” summed up a piece about the process in The Guardian, “the mice’s memory of what was pleasant and what was unpleasant had been reversed.”

The structure of the film is a rich object for study in itself. The very essence of “Eternal Sunshine” is analogous to the unstable process of remembering: remembering the order of events in a story, or the events in one’s own life. Or struggling to remember what happened. Or which thing happened first. And which thing happened after that? Did another thing happen third, or fourth, tenth? Did any of it happen, period? Are you superimposing your fantasies about who was at fault, and who did what to whom, onto events that were factual, and that could be proved or disproved in an objective record, had anyone thought to keep one? The record-keepers records might be faulty, too, or invested in lying or omitting. The movie is kaleidoscopic in its account of how things are remembered, misremembered and forgotten. The opening of the film could also be its ending, and its ending feels like a new beginning. The mouse remains stuck in the maze. When walls and corridors are deleted, and only blank space remains, the mouse struggles to remember the maze.