By Brian Eggert

Source: Deep Focus Review

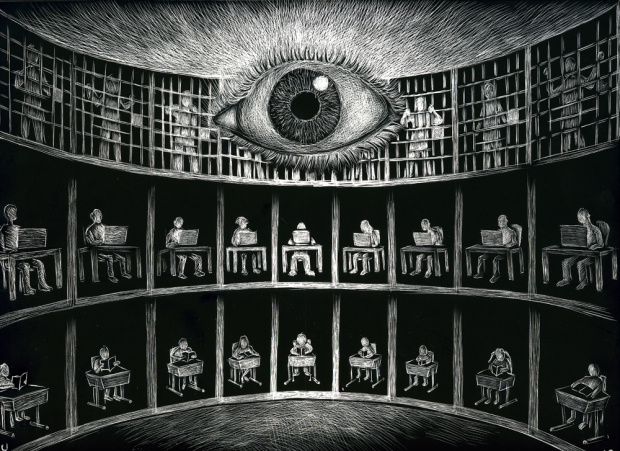

Spike Lee’s Bamboozled begs the question: When does artistic representation stop being a creative force and become something destructive? Released in 2000 to divisive assessments from both critics and audiences, the film raises questions through Lee’s flashpoint narrative and many-layered extratextuality. It concerns the history and lasting presence of negative African American stereotypes in mainstream entertainment; at the same time, and perhaps to more penetrating effect, it explores how negative representations in the media, even when they have an ironic or satirical objective, corrode cultural identities. To illustrate the infamous history of Black performers forced into demeaning roles, and the damaging outcome of entertainers who employ those images as commentary without due consideration of their intellectual and social ramifications, Lee dreamt up a transgressive film in which a provocative new television variety show, called Mantan: The New Millennium Minstrel Show, seeks to expose the most disdainful of Black stereotypes by featuring performers of color in minstrel makeup. It’s a show that employs grotesque caricatures in outrageous comic routines and dance numbers by tap artist Savion Glover, in effect hoodwinking its audience into applauding racist imagery. When the idea backfires and becomes a nationwide pop-culture phenomenon, the complicity of the creators and their audience comes into question—but so does Lee’s choice of using this imagery to make his point. Therein lies the problem that Lee wields and underscores in his meta-infused discussion. His film is designed to confront the viewer with the history and continued appearance of racial stereotypes in television and cinema, serving as an awakening and exorcism of these images. Whether it is successful has been a matter of some debate. Even so, Bamboozled supplies a necessary discussion about how African Americans are often depicted in television and cinema, and a maddening, deliriously made reminder of the dehumanizing consequences of the mainstream entertainment industry.

Bamboozled is satire wrapped in irony, with more satire piled on for good measure. Sifting through the influx of fast-paced stimuli, the director’s self-referential and self-critical humor, and the packed layers of commentary proved to be an understandable challenge for many. This is not an easy film to reconcile, if such a thing is even possible. Some critics, notably Roger Ebert, found the image alone of blackface so offensive that, despite it being used in a satiric format, he wrote in his review that he “had a struggle” to see beyond the image itself to find the satirical purpose underneath. “To ridicule something, you have to show it,” Ebert wrote. “And if what you’re attacking is a potent enough image, the image retains its negative power no matter what you want to say about it.” Critics other than Ebert called Lee’s approach to the material “unfocused” and “heavy-handed” and deemed it an “intriguing failure”—remarks that have accompanied many a Spike Lee joint. The message of the film, although interpreted as a commentary on race in the media, was often misunderstood. Writing in the New York Observer, Andrew Sarris missed the sweeping commentary and speculated, “If Mr. Lee meant to bring back blackface entertainment as a metaphor for the current Black performers he finds obnoxious, he has miscalculated.” Often seen as messy and full of thrilling contradictions, a rare few have judged Bamboozled to be one of Lee’s very best and most thought-provoking pictures. Among the few positive notices, The New York Times critic Stephen Holden wrote, “Its shelf life may not be long, nor will it probably be a big hit, since the laughter it provokes is the kind that makes you squirm.” Holden was right about his latter two claims, anyway—Bamboozled grossed only $2.2 million on a budget of $10 million for New Line Cinema.

It would not be the first nor last time Lee took the history of representation of people of color, and to a larger extent, mainstream white entertainment, to task. In 1980, during his first year at New York University film school, Lee made a short film called “The Answer,” about a struggling African American screenwriter who takes on a fifty-million-dollar remake of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915). However, the writer soon comes to his senses and backs out of the project, only to have crosses burned on his lawn by the Klu Klux Klan. Lee’s 20-minute film contains clips from The Birth of a Nation and generally calls out Griffith’s work for its racism. The faculty at NYU was not amused or impressed by Lee’s first effort, and some of them sought to have Lee removed from the program for his aggressive rejection of the film canon—as The Birth of a Nation is studied by some film historians and filmmakers as a monument of formal breakthroughs and techniques that other directors have learned from and borrowed. In an interview for The New Yorker, Lee told journalist John Colpatino, “They taught that D.W. Griffith is the father of cinema […] They talk about all the ‘innovations’—which he did. But they never really talked about the implications of Birth of a Nation, never really talked about how that film was used as a recruiting tool for the KKK.” Lee would later call out this fact in his thrilling 2018 procedural, BlacKkKlansman.

In a similar setup to “The Answer,” Bamboozled follows Pierre Delacroix (Damon Wayans), a Harvard graduate with a forced, inflected accent of superiority with which, in traditional film noir fashion (specifically Sunset Boulevard, 1950), he narrates the tale of his own demise. The sole Black television writer for cable network CNS, Delacroix has been reprimanded—by his white boss Dunwitty (Michael Rapaport), who says “I’m blacker than you”—for writing material that is “too white.” Delacroix is tasked with creating a new show that represents the racier side of race. In retaliation, Delacroix dreams up Mantan: The New Millennium Minstrel Show. Along with his assistant Sloan (Jada Pinkett Smith), he hires two homeless street performers, Manray (Savion Glover, from Bring in ‘Da Noise, Bring in ‘Da Funk) and Womack (Tommy Davidson), as his stars. Delacroix renames them “Mantan” and “Sleep-and-Eat,” after Black vaudevillian actors Mantan Moreland and Willie Best, and insists that the show’s all-Black cast perform in burnt cork blackface—the method used by original minstrel performers. Aside from Manray’s tap dancing, Delacroix arranges for Mantan to feature a litany of racist images and caricatures, including pickaninnies, Aunt Jemimas, Sambos, mammies, coons, and watermelon patches. After a lengthy and amusing audition process, Delacroix declares, “I don’t want to have anything to do with anything black for at least a week”—a remark that stands as a testament to his self-abasement. Despite some initial objections, Manray and Womack just want to perform, content notwithstanding. And anyway, Delacroix feels assured that no one in their right mind would approve such an over-the-top racist and politically incorrect program.

But in hoping to make a point about how the white public only wants to see Black people portrayed as buffoons and racist stereotypes, and by extension continue the dehumanizing process of slavery in another form of commodification, Delacroix’s hypothesis ironically proves true when, instead of rejecting Mantan, CNS executives, critics, and audiences soon embrace the show. When it’s picked up, Delacroix can say nothing except, “There must be some mistake.” In fact, Dunwitty, along with his blond-haired, Swedish-born director Jukka Laks (Jani Blom), insists on injecting “funnier” material—comedy even more offensive than Delacroix conceived. A gaggle of white writers who embrace Black stereotypes all too much carry the material even further. Before long, Mantan has top ratings and race-unspecific live audiences who show their affection for their favorite show by wearing blackface. As the creator of “the newest sensation across the nation,” Delacroix’s fame is boundless, yet he cannot control his “Frankenstein’s monster” creation. Not unlike Max Bialystock in The Producers (1967)—the Jewish stage producer whose intended failure, the Nazi-themed musical Springtime for Hitler, becomes a sensation—Delacroix’s guaranteed failure becomes a hit at considerable personal expense. However, after visiting his father, a standup comedian named Junebug (Paul Mooney), who drinks too much and lives from paycheck to paycheck, Delacroix resolves to embrace the success of his show over his father’s alternative example. He even enjoys the spoils of his efforts most opportunistically, accepting awards for his writing and becoming what he calls “Hollywood’s favorite Negro.”

With Delacroix’s love of success and gradual defense of his show, he begins to discount the power of negative African American stereotypes as modes of strengthening a white supremacist worldview. He adopts a “just go with it” attitude and concerns himself more with the humor and sensationalism of the show, detaching himself from the social implications. Sloan argues that he cannot afford to deceive himself into ignoring their history as if it doesn’t matter, as it’s a form of soul-crushing self-hatred. But Delacroix dismisses the significance of racialized slavery, which he claims ended “400 years ago,” as insignificant in the modern world. “We need to stop thinking that way, stop crying over ‘the white man this, the white man that.” He adds, “This is the new millennium, and we must join in.” Sloan refuses to forget, soberly reminding Delacroix, Manray, and Womack about the history of such imagery. Later in the film, after the show becomes a hit, Sloan gives Delacroix a toy from the turn of the twentieth century called a “Jolly Nigger Bank” to remind him “of a time in our history in this country when [people of color] were considered inferior, subhuman, and we should never forget that.” Sloan wants Delacroix—who is so filled with self-hatred, so disgusted with his own identity as a Black man that he has changed his name from Peerless Dothan to the more “white-sounding” name—to look at the toy and ask, “Whose puppet are you?”

Sloan is Delacroix’s conscience and, therefore, the moral center of Bamboozled. She’s suspicious of Mantan from the start, and she questions any representation that could become a form of minstrelsy or contain racist overtones. Lee’s greater argument in the film is how blackness itself has become a pop-culture gimmick and warns of the dangers of falling prey to this sales pitch. Consider Sloan’s critical attitude toward her brother (Mos Def), a rapper nicknamed Big Blak Afrika, and his Black-obsessed radical outfit called the Mau Maus, named after the anticolonial uprising in Kenya that lasted from 1952 to 1960. The group dons entirely black clothing and produces a new album called “The Black Album,” but they also support detrimental stereotypes by drinking 64 oz. malt liquor called “Da Bomb” and wearing “Timmy Hillnigger” fashions—two products which Lee’s film presents in faux commercials that demonstrate a modern form of stereotyping evident in advertising and media. Lee argues that the popularization of African Americans in culture has resulted in “blackness” having a new set of cultural signifiers, which is another, somehow socially acceptable form of racism. Saying “I’m black” no longer refers to race or color for characters in the film; blackness becomes less a cultural identity than a pop-culture phenomenon. When the Mau Maus are shot down by the police in the third act of the film, the sole white member remains standing, shouting in desperation, “Why didn’t you shoot me too? I’m black!” Elsewhere, Dunwitty claims to have more experience with blackness than Delacroix: “I got a Black wife and three bi-racial children,” he asserts, defending his overt cultural appropriation. As for Dunwitty’s liberal use of the N-word, he will not apologize, in spite of “what that prick Spike Lee” said in his highly publicized debate over Quentin Tarantino’s use of the word in his films.

As a satire, Bamboozled exists in the same realm as Elia Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd (1957) and Sidney Lumet’s Network (1976), each about an unbelievable cultural phenomenon that sweeps through America like a plague. The ignorant masses embrace the sensation, whereas a few characters in each picture see the harmful extent of what they have done. In Bamboozled, Womack, who went along with Mantan to get off the street and earn some money, finally leaves the show: “It’s the same bullshit,” he says, “Just done over.” When Manray too realizes the extent of what he’s done by “This buck dancing, this blackface shit,” he makes his way to the stage free of blackface and announces, “Cousins, I want you to go to your window, yell out, scream with all the life you can muster up inside your bruised and battered and assaulted bodies, ‘I’m sick and tired of niggers and I’m not gonna take it anymore!’” This clear nod to Peter Finch’s pronouncement in Network, “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!” implies that minstrelsy allows the audience to take pleasure in white-comforting racial stereotypes, which by extension assumes the inferiority of another race of human beings and denies their equal share of humanity. But it’s also this moment where Bamboozled forgoes sending up these images and routines and transforms itself into a powerful melodrama.

Lee brings his film to a fitting, tragic conclusion. Could Bamboozled end any other way? Confronted by his part on the show and his role in its cultural degradation, Manray quits, only to be kidnapped by the Mau Maus and executed on the internet in retaliation. The authorities then corner the Mau Maus and kill, among the others, Big Blak Afrika. Shaken by Manray and her brother’s death, Sloan confronts Delacroix in his apartment, where she finds him at his lowest and most guilt-ridden, donning blackface in an act of shame and self-destruction. She accuses Delacroix and his show of causing all this death and cultural anarchy, and she shoots him in the stomach—an action for which he immediately forgives by telling her “It’s okay,” as if he now recognizes that he must die. Lee’s rather classical approach here, harkening back to film noir again, punishes the wicked for their misdeeds in perpetuating racist stereotypes. The ruthless violence with which he excises the film’s evildoers who have contributed to demeaning minstrel imagery is grandiose and arguably excessive, but nothing about Bamboozled is anything less than heightened, and in this context, the punishment fits the crime. As Delacroix dies, Sloan puts on a videotape with a procession of footage, racist images from American cultural history. In the punishing three-minute montage that follows, the videotape shows images from Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, The Jazz Singer (1927), Gone with the Wind (1939), Holiday Inn (1942), Ub Iwerks’ cartoon “Little Black Sambo” (1935), the Merrie Melodies short “All This and Rabbit Stew” (1941), and the sitcom Amos ‘n Andy (1951-1953). The list goes on and on, and Lee sets it against a nightmarish laugh track to accentuate its horror with appalling irony.

As the montage comes to a close, Lee returns to Delacroix’s noirish voiceover for a final, oblique statement that underlines the persistence of Black performers conforming to negative racial stereotypes in American entertainment: “As I bled to death, as my very life oozed out of me, all I could think of was something that the great Negro James Baldwin had written: ‘People pay for what they do, and still more for what they have allowed themselves to become, and they pay for it very simply by the lives they lead.’ Maybe Baldwin was right, maybe he was wrong. But as my father often told me, always keep ‘em laughing.” With that, Lee returns to an image of Manray in his Mantan garb, an unsettling close-up of his face, dappled with beads of sweat atop the corked-up blackface makeup, holding an exaggerated through-the-pain smile. Manray takes one pose after another as an off-screen crowd cheers, and Lee holds the shot for an unbearably long time. And in doing so, he asks the viewer to think about the roles people of color, such as Hattie McDaniel or Eddie Anderson, were forced to play historically, whereas today, Black entertainers have more choice in the matter. Lee told Allison Samuels in Newsweek, “Nowadays we don’t have to do this stuff.” But Lee’s argument with Bamboozled is that such stereotypes remain prevalent in American entertainment because, in part, too few Black performers have learned from past examples, but worse, the trends in entertainment remain a mere sample of the larger problems within American society.

By conforming to pop-culture demands, Delacroix convinces himself to carry on harmful traditions by distancing himself from his own race and refusing to acknowledge the power of the imagery he resolved to employ, even for satirical and comic purposes. It’s the very thing that has sparked Lee’s criticism of similar real-life television shows, including Keenen Ivory Wayans’ Emmy-winning In Living Color, a sketch-comedy and variety show that aired on Fox between 1990 and 1994. The show gave a start to comedians and performers like Jamie Foxx, David Alan Grier, Jim Carrey, and Jennifer Lopez, but it also employed negative stereotypes for the sake of comedy, sometimes using motifs that originated in minstrelsy. Lee has been vocal about his critiques of In Living Color, a show he references in Bamboozled. He also hired the program’s former cast members, Wayans and Davidson, in conspicuous roles that at once atone for and magnify the show’s occasionally problematic representations. Wayans, in particular, has had a complex if bankable career playing sometimes troubling stereotypes, evidenced in the feature films Mo’ Money (1992), Blankman (1994), and Major Payne (1995). The connections between In Living Color and Mantan may not be one-to-one, but they have a similar effect on their viewers, encouraging a racially diverse mainstream audience to laugh at harmful imagery. Lee’s film incites his audience to question our willingness to laugh at such material and, instead, think about the cultural consequences of that laughter.

Lee’s commentary would prove not only reflective but prescient. A more recent example that follows In Living Color’s legacy was the oft-scandalous Chappelle’s Show (2003-2006), Comedy Central’s sketch-comedy hit whose journey through American pop-culture mirrored Bamboozled. The show famously ended at its height after star Dave Chappelle left the production, questioning if his show was making fun of stereotypes or reinforcing them. The catalyst for Chappelle leaving the show came as he filmed a sketch for the third season in November 2004, about “magic pixies that embody stereotypes about the races.” In the sketch, Chappelle plays a Black pixie and wears blackface, and he tries to convince people of color to behave in a stereotypical manner. But as Chappelle told Time magazine interviewer Christopher John Farley, when a white crew member laughed, he began to question whether he started reinforcing stereotypes instead of lampooning them, and his crisis of conscience led to Chappelle leaving the show. In the cases of both Delacroix and Chappelle, when they embrace their respective shows’ racist material, they forget that such damaging imagery of African Americans exists and conveniently ignore that fact for the sake of humor and entertainment. Anything to “feed the idiot box,” as Delacroix reminds himself. Harsher critics of Bamboozled might argue that Lee engages in the same irresponsible form of representation in his film; however, Bamboozled is not a pure comedy for the masses. It recycles what is appealing about minstrel shows—such as the talent required to carry out “coon” routines, as they’re referred to—and through them represents and opens up a discussion about their dangers in the film’s violent third act.

Lee’s maximalist aesthetic on the film—replete with jagged editing by Sam Pollard that switches freely amid cinematographer Ellen Kuras’ multiple cameras—aligns with his subject matter in its disorienting effect. Bamboozled was shot fast almost entirely on consumer-grade digital cameras, in a period before digital was the industry standard, and then later converted to 35mm for a grainy and dreary-looking outcome. The Mantan show sequences were filmed on Super-16mm film stock to contrast the gritty everyday scenes shot on digital and accentuate the performers’ cork-black and “fire engine red” makeup. Lee and Kuras steeped the film set with multiple cheap cameras for maximum coverage, which in turn reduced the production’s costs. The approach is most evident through Pollard’s kinetic editing, a style that often repeats a particular moment two or three times for emphasis. Extreme low angles, conversely muted and color-saturated palettes, and a pointedly digital look give the entire film the suspicious quality of home-movie reality. And yet, the exaggerated situations and performances (most expressly Wayans and Rapaport), present a juxtaposition that forces the viewer to think about Bamboozled as a reflection of how African Americans in entertainment and advertising are portrayed. All the while, the forlorn music by Terence Blanchard, in one of his very best scores for Lee, imbues the material with weighty implications far removed from satire alone.

However challenging and outlandish Bamboozled may have seemed in 2000, it’s not such a fantasy today—certainly not after life imitated Lee’s art to such an extreme with Chappelle’s Show. Perhaps this is why critics and scholars have kept returning to the film over the years and discovering, through its many layers, the brilliant complexity of Lee’s film. Admittedly, I was uncomfortable, exhausted, and skeptical about the film upon first seeing it, but gradually, I came to recognize how much of Bamboozled proved true in the ensuing years, and along with repeated viewings, I have recognized that much of what Lee discusses in the film continues to play out in our entertainment and society today. One need not look further than the Rachel Dolezal incident in 2015, when the NAACP leader at the Spokane branch turned out to be a white woman posing as African American. And critic Ashley Clark wrote in his book about the film, Facing Blackness, that Bamboozled was “effectively howling with hallows laughter at the utopian notion of a ‘post-racial society’ eight years before the concept gained traction with the election of President Barack Obama.” Whether it’s entertainment we consume or our response to public figures, Lee’s film leads to bigger questions about appropriation—and about what scholar Michael Rogin, writing in Cineaste, called minstrelsy’s “white form of appropriative access to imagined black experience”—which resonates in ways that many American audiences could not recognize in their society or predict for their future at the time of Bamboozled’s release.

Then again, maybe we should have anticipated that Lee was ahead of the curve. Lee’s approach had already been thoroughly demonstrated by the time Bamboozled was unleashed into theaters. With School Daze (1988), Do the Right Thing(1989), Malcolm X (1992), and other films, Lee draws historical parallels by using images from the past that relate to our present, reminding us that the roots of history are sometimes right under our feet. It’s a method he employed on BlacKkKlansmanas well—in a screenplay that finally earned Lee an Oscar—by drawing comparisons between the KKK in The Birth of a Nation, the KKK in Colorado Springs in the 1970s, and the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville. Similarly with Bamboozled, Lee investigates history to call out how television and cinema rarely have a place for African Americans outside of stereotypes, negative or otherwise—even in Oscar-winning roles for actors of color, from Octavia Spencer’s sassy maid in the white-savior feel-good drama The Help(2011) to Lupita Nyong’o’s role as a slave in Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave(2013). Nevertheless, Lee knows that the issues and dynamics concerning race in America are complex and multifaceted, that they demand investigation and debate. And he knew that his appropriately-named film would be met with confusion, anger, misunderstanding, and frustration—but that’s the point, evidenced by his use of a clip of Denzel Washington’s performance in Malcolm X and his line, “You’ve been hoodwinked. You’ve been had. You’ve been took. You’ve been led astray. Led amok. You’ve been bamboozled.”

Bamboozled’s passionate and provocative look at the stereotypes faced by African Americans has prompted responses ranging from outrage to laughter, empathy to sadness, anger to acknowledgment. Though a controversial choice, Lee allows his audience to experience first-hand the dangerously entertaining appeal and humor derived from minstrel acts, and through it, he demands that his audience reflects on the consequences of such representations. Just as Delacroix intended for Mantan, Lee wants to offend; he argues that if you aren’t offended or questioning the material, there’s something very wrong. Lee told Cineaste in a 2001 interview, “I want people to think about the power of images, not just in terms of race, but how imagery is used and what sort of social impact it has […] I want them to see how film and television have historically, from the birth of both mediums, produced and perpetuated distorted images. Film and television started out that way, and here we are, at the dawn of a new century and a lot of that madness is still with us.” Although no certainty or universality will ever be reached about what representations should be considered appropriate or how far is going too far, the discussion is crucial to understanding our feelings on the subject. Even if Lee’s only intent with Bamboozled was to ignite fiery discourse about race and representation in entertainment, his film remains a rousing achievement as both art and a social prompt.

____________________

Watch Bamboozled on Hoopla here: https://www.hoopladigital.com/title/16138885