Tag Archives: Precariat

The Economic Cataclysm Ahead

By Charles Hugh Smith

Source: Of Two Minds

The economic storm hasn’t passed; the false calm is only the eye of the financial hurricane.

To understand the economic cataclysm ahead, do the math. Those expecting the Covid-19 pandemic to leave the U.S. economy untouched are implicitly making these preposterously unlikely claims:

1. China will resume full pre-pandemic production and shipping within the next two weeks.

2. Chinese consumers will resume borrowing and spending at pre-pandemic rates in a few weeks.

3. Every factory and every worker in China will resume full pre-pandemic production without any permanent closures or disruptions.

4. Corporate America’s just-in-time inventories will magically expand to cover weeks or months of supply chain disruption.

5. Not a single one of the thousands of people who flew direct from Wuhan to the U.S. in January is an asymptomatic carrier of the coronavirus who escaped detection at the airport.

6. Not a single one of the thousands of people who flew from China to the U.S. in February is an asymptomatic carrier of the coronavirus.

7. Not a single one of the thousands of people who are in self-quarantine broke the quarantine to go to Safeway for milk and eggs.

8. Not a single person who came down with Covid-19 after arriving in the U.S. feared being deported so they did not go to a hospital and are therefore unknown to authorities.

9. Even though U.S. officials have only tested a relative handful of the thousands of people who came from Covid-19 hotspots in China, they caught every single asymptomatic carrier.

10. Not a single asymptomatic carrier caught a flight from China to Southeast Asia and then promptly boarded a flight for the U.S.

I could go on but you get the picture: an extremely contagious pathogen that is spread by carriers who don’t know they have the virus to people who then infect others in a rapidly expanding circle has been completely controlled by U.S. authorities who haven’t tested or even tracked tens of thousands of potential carriers in the U.S.

These same authorities are quick to claim the risk of Covid-19 spreading in the U.S. is low even as the 14 infected people they put on a plane ended up infecting 25 passengers on the flight. These same authorities tried to transfer quarantined people to a rundown facility in Costa Mesa CA that was not suitable for quarantine, forcing the city to file a lawsuit to stop the transfer.

Do these actions instill unwavering confidence in the official U.S. response? You must be joking.

Do the math, people. The coronavirus is already in the U.S. but authorities have no way to track it due to its spread by asymptomatic carriers. People who don’t even know they have the virus are flying to intermediate airports outside China and then catching flights to the U.S.

None of the known characteristics of the virus support the confidence being projected by authorities. The tests are not reliable, few are being tested, carriers can’t be detected because they don’t have any symptoms, the virus is highly contagious, thousands of potential carriers continue to arrive in the U.S., etc. etc. etc.

The network of global travel remains intact. Removing a few nodes (Wuhan, etc.) does not reduce the entire network’s connectedness that enables the rapid and invisible spread of the virus.

Second, what authorities call over-reaction is simply prudent risk management. As I noted yesterday in How Many Cases of Covid-19 Will It Take For You to Decide Not to Frequent Public Places?, when an abstract pandemic becomes real, shelves are emptied and streets are deserted.

It doesn’t take thousands of cases to trigger a dramatic reduction in the willingness to mix with crowds of strangers. A relative handful of cases is enough to be consequential.

Many of the new jobs created in the U.S. economy over the past decade are in the food and beverage services sector, the sector that is immediately impacted when people decide to lower their risk by staying home rather than going out to crowded restaurants, theaters, bars, etc.

Many of these establishments are hanging on by a thread due to soaring rents, taxes, fees, healthcare and wages. Many of the employees are also hanging on by a thread, only making rent if they collect big tips.

Central banks can borrow money into existence but they can’t replace lost income. A significant percentage of America’s food and beverage establishments are financially precarious, and their exhausted owners are burned out by the stresses of keeping their business afloat as costs continue rising. The initial financial hit as people reduce their public exposure will be more than enough to cause many to close their doors forever.

As small businesses fold, local tax revenues crater, triggering fiscal crises in local government budgets dependent on ever-higher tax and fee revenues.

A significant percentage of America’s borrowers are financially precarious, one paycheck or unexpected expense away from defaulting on student loans, subprime auto loans, credit card payments, etc.

A significant percentage of America’s corporations are financially precarious, dependent on expanding debt and rising cash flow to service their expanding debt load. Any hit to their revenues will trigger defaults that will then unleash second-order effects in the global financial system.

The global economy is so dependent on speculative euphoria, leverage and debt that any external shock will tip it over the cliff. The U.S. economy is far more precarious than advertised as well.

The economic storm hasn’t passed; the false calm is only the eye of the financial hurricane.

The Unraveling Quickens

By Charles Hugh Smith

Source: Of Two Minds

Even if we don’t measure the erosion of intangible capital, the social and political consequences of this impoverishment are manifesting in all sorts of ways.

The central thesis of my new book Will You Be Richer or Poorer? is the financial “wealth” we’ve supposedly gained (or at least a few of us have gained) in the past 20 years has masked the unraveling of our intangible capital: the resilience of our economy, our social capital, i.e. our ability to find common ground and solve real-world problems, our sense that the playing field, while not entirely level, is not two-tiered, and our sense of economic security–have all been shredded.

The unraveling of everything that actually matters is quickening. While every “news” outlet cheerleads the stock market (“The Dow soared today as investor optimism rose… blah blah blah”), our “leadership” and our media don’t even attempt to measure what’s unraveling, much less address the underlying causes.

The hope is that if we ignore what’s unraveling, it will magically go away. But that’s not how reality works.

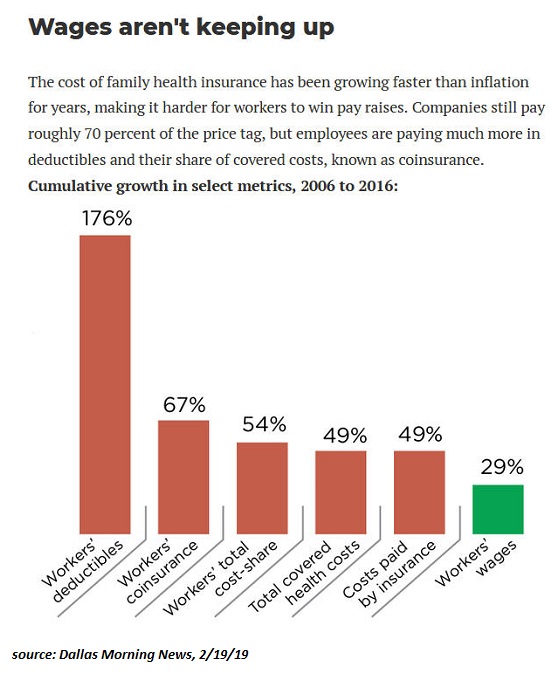

The unraveling is gathering momentum because prices have been pushing higher while wages lag, feeding the rising precariousness and inequality of our economy. The connection between people losing ground and social disorder/disunity has been well established by historians such as Peter Turchin Ages of Discord and David Hackett Fischer The Great Wave: Price Revolutions and the Rhythm of History.

In our era, trust in the legitimacy of our institutions is unraveling because the statistics presented as “facts” are so clearly designed to support the status quo narrative that everything’s getting better every day in every way rather than the politically unwelcome reality that the bottom 95% are losing ground and whatever they do earn and own is increasingly at risk from forces outside their control.

Economic decay leads to social and political disorder / disunity. The sudden rise of vast homeless encampments is one manifestation of the social fabric unraveling. In the political realm, the insanity of accusing Democratic candidates of being “Russian agents” matches the hysterical destructiveness of the McCarthy era in the 1950s.

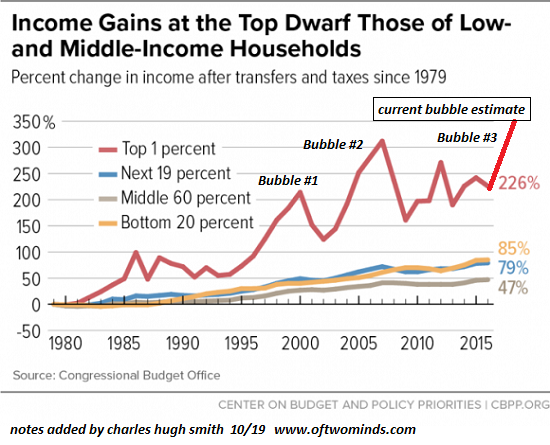

It all starts with economic decay, so let’s look at some charts. Here’s a chart of income inequality which helps drive wealth inequality.

Note that the only group that benefited from the past 20 years of speculative bubbles is the top 1%. The whole idea that inflating bubbles creates a “wealth effect” that “trickles down” is preposterous, as evidenced by the decline of the middle 60% of households while the speculators and owners of bubble-assets skimmed the vast majority of income gains.

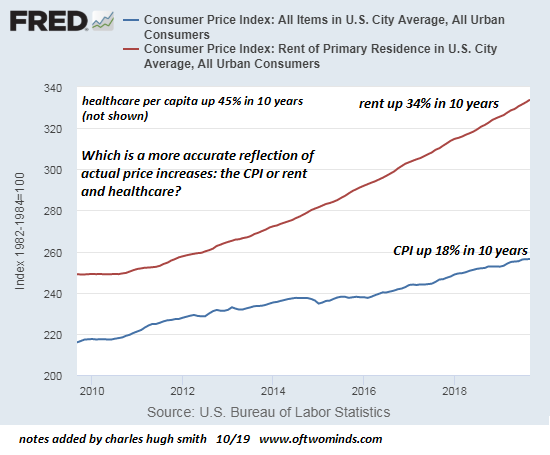

Meanwhile, we’re told inflation is less than 2% annually while rising costs have outpaced meager wage increases. What’s a more realistic measure of real-world inflation–the official Consumer Price Index (CPI) at 18% over ten years or rent and healthcare at 34% and 45%?

According to the Chapwood Index, real-world inflation in urban America is running 9% to 13% annually. This is more in line with reality than the bogus CPI, as evidenced by this chart of wages and healthcare costs:

Even if we don’t measure the erosion of intangible capital, the social and political consequences of this impoverishment are manifesting in all sorts of ways: large-scale social disorder is breaking out around the globe, and the political middle ground has completely vanished: no matter which way an issue is decided, one camp will refuse to accept the outcome.

The only way forward with any chance of success is to start by acknowledging the decay of our economy due to rampant financialization, legalized looting, the pathologies of “winner take most” speculation and the realities of a two-tiered system in which entrenched elites are “more equal” than the rest of us, economically, socially and politically. We have to accept the limits of technology to reverse the unraveling and assess the damage that’s already been done to our shared capital.

Acting as if the system is working just fine and the problem is perception/optics is accelerating the unraveling.

Is the U.S. Becoming a Third World Nation?

By Charles Hugh Smith

Source: Of Two Minds

This is a chart of an informal kleptocracy which cloaks itself in the faux finery of democracy and a (rigged) “market” economy.

Back in the day, nations that didn’t qualify as either developed (First World) or developing (Second World) were by default Third World, impoverished, corrupt and what we now refer to as failed states–governments that were incapable of improving the lives of their people and the machinery of governance, generally as a result of corruption and self-serving elites, i.e. kleptocracies.

Is the U.S. slipping into Third World status? While many scoff at the very question, others citing the rise of homelessness, entrenched pockets of abject poverty and the decaying state of infrastructure might nod “yes.”

These are not uniquely Third World problems, they’re symptoms of a status quo that’s fast losing First World capabilities. What characterizes Third World/Failing States isn’t just poverty, crumbling infrastructure and endemic corruption; at a systems level these are the key dynamics in Third World/Failing States:

1. The status quo protects insiders at the expense of everyone else.

2. There is no real accountability; failure has no consequences, bureaucrats are never fired for incompetence, reforms are watered down or neutered by institutional sclerosis.

3. Pay-to-play is the most cost-effective way to influence policy or evade consequences.

4. The status quo is incapable of differentiating between complexity that serves the legitimate purposes of transparency and accountability and complexity that serves no purpose beyond guaranteeing insiders’ paper-shuffling jobs. As a consequence, complexity that adds no value chokes the economy and the government.

5. There are two sets of laws: one for insiders and the super-wealthy, and another harsher set for everyone else.

6. The super-wealthy fear nothing because the system functions to serve their interests.

7. The super-wealthy and state insiders control the media’s narratives and the machinery of governance to serve their interests. Reforms are in name only; the faces of elected officials change but nothing changes structurally.

8. Insiders, well-paid pundits and the technocrats serving the corporate and state elites believe the status quo is just fine because they’re doing fine; they are blind to the soaring inequality, systemic corruption, stupendous waste and the impossibility of real reform.

Does America’s status quo protect insiders at the expense of everyone else? Yes. As for the other seven characteristics: yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes and yes.

And lets’ not forget #9: the vast majority of the economic gains flow to the elite at the very top of the wealth-power pyramid: is this true in the U.S.? Definitively yes. Just look at this chart: this is a chart of an informal kleptocracy which cloaks itself in the faux finery of democracy and a (rigged) “market” economy.

That’s the very definition of a Third World failed state.

Related Video:

Jeff Bezos’s Corporate Takeover of Our Lives

Illustration by Mike Faille

How Amazon’s relentless pursuit of profit is squeezing us all—and what we can do about it

By David Dayen

Source: In These Times

AMAZON IS AN ONLINE RETAILER. It also runs a marketplace for other online retailers. It’s also a shipper for those sellers, and a lender to them, and a warehouse, an advertiser, a data manager and a search engine. It also runs brick-and-mortar bookstores. And grocery stores.

There are over 100 million Amazon Prime subscribers in the United States—more than half of all U.S. households. Amazon makes 45 percent of all e-commerce sales. Amazon is also a product manufacturer; its Alexa controls two-thirds of the digital assistant market, and the Kindle represents 84 percentof all e-readers. Amazon created its own holiday, Prime Day, and the surge in demand for Prime Day discounts, followed by a drop afterward, skewed the nation’s retail sales figures with a 1.8% bump in July 2017.

Oh, it’s also a major television and film studio. Its CEO owns a national newspaper. And it runs a streaming video game company called Twitch. And its cloud computing business, Amazon Web Services, runs an astonishing portion of the Internet and U.S. financial infrastructure. And it wants to be a logistics company. And a furniture seller. It’s angling to become one of the nation’s largest online fashion designers. It recently picked up an online pharmacy and partnered with JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon and Warren Buffett to create a healthcare company. And at the same time, it’s competing with JPMorgan, pushing Amazon Pay as a digital-based alternative to credit cards and Amazon Lending as a source of capital for its small business marketplace partners.

To quote Liberty Media chair John Malone, himself a billionaire titan of industry, Amazon is a “Death Star” moving its super-laser “into striking range of every industry on the planet.” If you are engaging in any economic activity, Amazon wants in, and its position in the market can distort and shape you in vital ways.

Elizabeth Warren’s proposal to break up Amazon, along with the FTC’s new oversight and investigation, has spurred a conversation on the Left about its overwhelming power. No entity has held the potential for this kind of dominance since the railroad tycoons of the first Gilded Age were brought to heel. Whether you share concerns about Amazon’s economic and political power or you just like getting free shipping on cheap toilet paper, you should at least know the implications of living in Amazon’s world—so you can assess whether it’s the world you want, and how it could be different.

BOOKSELLERS WERE THE FIRST TO FIND THEMSELVES AT THE TIP OF AMAZON’S SPEAR, at the company’s founding in 1994. Years of Amazon peddling books below cost shuttered thousands of bookstores. Today, Amazon sells 42 percent of all books in America.

With such a large share of the market, Amazon determines what ideas reach readers. It ruthlessly squeezes publishers on wholesale costs; in 2014, it deliberately slowed down deliveries of books published by Hachette during a pricing dispute. By stocking best-sellers over independents and backlist copies, and giving publishers less money to work with, Amazon homogenizes the market. Publishers can’t afford to take a chance on a book that Amazon won’t keep in its inventory. “The core belief of bookselling is that we need to have the ideas out there so we can discuss them,” says Seattle independent bookseller Robert Sindelar. “You don’t want one company deciding, only based on profitability, what choice we have.”

These issues in just the book sector are a microcosm of Amazon’s effect on commerce.

The term “retail apocalypse” took hold in 2017 amid bankruptcies of established chains like The Limited, RadioShack, Payless ShoeSource and Toys “R” Us. According to frequent Amazon critic Stacy Mitchell, “more people lost jobs in general-merchandise stores than the total number of workers in the coal industry” in 2017.

Amazon isn’t the only cause; private equity looting must share much of the blame, and a shift to e-commerce was always going to hurt brick-and-mortar stores. But Amazon transformed a diverse collection of website sales into one mammoth business with the logistical power to perform rapid delivery of millions of products and a strategy to underprice everyone. That transformation accelerated a decline going back to the Great Recession (and much earlier for booksellers). Analysts at Swiss bank UBS estimate that every percentage point e-commerce takes from brick-and-mortar translates into 8,000 store closures, and right now e-commerce only has a 16 percent market share.

Take Harry Copeland (or, as he calls himself, “Crazy Harry”) of Harry’s Famous Flowers in Orlando, Fla., at one time a 40-employee retail/wholesale business. Revenue at his operation has shrunk by half since 2008, equal to millions of dollars in gross sales. “The internet … killed us,” Harry says. “I was in a Kroger, this guy walks up and says, ‘I want to apologize. It’s so easy to go on the internet.’ I said, ‘I did your wedding, I did flowers for your babies, and you’re buying [flowers] on the internet?’ ” Even Harry’s own employees receive Amazon packages at the shop every day. In January, tired of the fight, Harry sold his shop after 36 years in business.

Amazon was particularly deadly to the original “everything stores,” the department stores like Sears and J.C. Penney that anchor malls. When the anchor stores shut down, foot traffic slows and smaller shops struggle. Retailers are planning to close more than 4,000 stores in 2019; the 41,201 retail job losses in the first two months of this year were the highest since the Great Recession.

Dead malls trigger not only blight but also property tax losses. The broader shift to online shopping also transfers economic activity from local businesses to corporate coffers, like Amazon’s headquarters in Seattle.

Some of these failed retail spaces have been scooped up, ironically, by Amazon’s suite of physical stores, such as Whole Foods. Amazon also skillfully pits cities against one another and wins tax breaks for its warehouse and data center facilities, starving local budgets even more.

Amazon, of course, argues it is the best friend small business ever had. Jeff Bezos’ 2019 annual letter indicated that 58% of all sales on the website are made by over 2 million independent third-party sellers, who are mostly small in size. In this rendering, Amazon is just a mall, opening its doors for the little guy to access billions of potential customers. “Third-party sellers are kicking our first-party butt,” Bezos exclaimed.

It was a line I repeated to several merchants, mostly to snickers. Take Crazy Harry. In late 2017, Amazon reached out with the opportunity for Harry’s Famous Flowers to sell through its website. Sales representatives promised instant success. “We went live in November,” he says. “I made three transactions, [including] one on Valentine’s Day and one on Christmas.” The closest delivery to his shop was 34 miles away. By the time Harry paid his $39.99 monthly subscription fee for selling on Amazon and a 15% cut of sales, his check came to $6.92. “The gas was $50,” he says.

It wasn’t hard to find the source of the trouble: When Harry searched on Amazon under “flowers in Orlando,” his shop didn’t come up. Without including his name in the search, there was no way for customers to find him. Before long, Harry closed his Amazon account.

Crazy Harry’s troubles could be a function of Amazon running a platform that’s too big to manage. Two million Americans, close to 1% of the U.S. population, sell goods on Amazon. “There’s so much at stake for these sellers,” says Chris McCabe, a former Amazon employee who now runs the consulting site eCommerceChris.com. “They’ve left jobs [to sell on Amazon]. They are supporting themselves and their families.”

Third-party sellers have been a great deal for Amazon—unsurprisingly, since Amazon sets the terms. Sellers pay a flat subscription fee and a percentage of sales, and an extra fee for “Fulfillment by Amazon,” for which Amazon handles customer service, storage and shipping through its vast logistics network. Fee revenue grew to nearly $43 billion in 2018, equal to more than one out of every four dollars that third-party sellers earned.

In other words, Amazon is collecting rent on every sale on its website. This strategy increases selection and convenience for customers, but the sellers, who have nowhere else to go, can get squeezed in the process. Once on the website, sellers are at the mercy of Amazon’s algorithmic placement in search results. They must also navigate rivals’ dirty tricks (like fake one-star reviews that sink sellers in search results) and counterfeit products. And if you get past all that, you must fight the boss level: Amazon, which has 138 house brands. Armed with all the data on sellers’ businesses, Amazon can easily figure out what’s hot and what can be cheaply produced, and then out-compete its own sellers with lower prices and prioritized search results.

Any failure to follow Amazon’s always-changing rules of the road can get a seller suspended, and in that case, Amazon not only stops all future sales, but refuses to release funds from prior sales. And all sellers must sign mandatory arbitration agreements that prevent them from suing Amazon. Several consultants I interviewed talked of sellers crying on the phone, finding themselves trapped after upending their lives to sell on Amazon.

WHILE RETAIL WORKERS LOSE JOBS, AMAZON PICKS UP SOME OF THE UNEMPLOYMENT SLACK, hiring personnel to assemble its packages, make its electronics, and deliver its goods, with a U.S. workforce of more than 200,000, and another 100,000 seasonal workers—though 2018 research from the Conference Board confirmed the jobs created by e-commerce companies like Amazon do not make up for the loss of millions of retail jobs.

Plus, the experience of being a cog in Amazon’s great machine is, shall we say, unhealthy. We know much about the horrors of being an Amazon warehouse worker in the United States. These workplaces are aggressively anti-union. Amazon sets quotas for how many orders are fulfilled, monitoring a worker’s every move. Poor performers may be fired, typically over email. The daily monotony and pressure to perform has pushed workers to suicidal despair. A Daily Beast investigation found 189 instances between October 2013 and October 2018 of 911 calls summoning assistance to deal with suicide attempts or other mental-health emergencies at Amazon warehouses. And even these grunt jobs are insecure; Amazon had to reassure people this year that it wouldn’t turn over all warehouse jobs to robots, even as it rolled out machines that box orders.

Amazon’s other jobs, while less scrutinized than the warehouse workers, can be just as brutal. Thousands of delivery drivers wear Amazon uniforms, use Amazon equipment and work out of Amazon facilities. But they are not technically Amazon employees; they work for outside contractors called delivery service partners. These workers do not qualify for the guaranteed $15 minimum wage Bezos announced to much fanfare last year.

Contracting work out lets Amazon dodge liability for poor labor practices, a trick used by many corporations. At one such contractor in the mid-Atlantic, TL Transportation, one former employee (who requested anonymity) described the work as “running, running, running, rushing. There was no break time.” According to pay stubs, TL built two hours of overtime into its base rate, which is illegal under U.S. labor law. Other workers reported they always worked longer than the time on their pay stubs. Driver Tyhee Hickman of Pennsylvania testified to having to urinate into bottles to maintain the schedule.

Amazon runs plenty of air freight these days as well, through an “Amazon Air” fleet of planes branded with the Amazon logo—but these are also contracted out. At Atlas Air, one of three cargo carriers with Amazon business, pilots have been working without a new union contract since 2011. Atlas pays pilots 30% to 60% below the industry standard, according to Captain Daniel Wells, an Atlas Air pilot and president of the Airline Professionals Association Teamsters Local 1224. Planes are understaffed. “We’ve been critically short of crews,” Wells says. “Everyone is scrambling to keep operations going.”

The go-go-go schedule leaves little time for mechanics; planes go out with stickers indicating deferred maintenance. One Atlas Air flight carrying Amazon packages crashed in Texas in February, killing three workers.

EVEN WHILE DRIVING WORKERS AT A FRENETIC PACE, Amazon doesn’t always deliver on its promise of convenience and efficiency. Many products no longer arrive in 48 hours under Prime’s guaranteed two-day shipping. It’s so challenging to reach customer service that Amazon sells a book on its website about how to do that. Whole Foods shoppers who have groceries delivered get bizarre food substitutions without warning.

Even as two-day shipping is creaking, Amazon has announced a move to one-day shipping, which will strain its systems even further while forcing competitors to adjust. Amazon’s one-day shipping announcement alone caused retail stocks to plummet on April 26, before any changes were implemented.

This feedback effect reveals how Amazon is not merely riding the wave of online retail’s convenience; only a company with ambitions as vast as Amazon’s could influence Fortune 500 business models across America.

Some retailers have given in. Walmart quickly announced its own next-day shipping. Kohl’s sells Amazon Echo devices. Target has bought up competitors to compete with Amazon on a larger scale. Call it concentration creep; one giant business triggers the need for others to get big, too. Corporate America is at once terrified of Amazon and reshaping itself to imitate it.

Take Amazon’s ever more sophisticated ploys to modify consumer behavior. With “personalized pricing,” Amazon uses the data of what someone has paid in the past to test what that person is willing to pay. The price of an item featured in the “buy” box on Amazon’s website may change multiple times per day, and can be tailored to individual shoppers. Amazon has charged more for Kindles based on a buyer’s location, and has steered people to higher-priced products where it makes a greater profit, rather than cheaper versions from outside sellers.

Now, even big-box stores have electronic price tags that retailers can “surge price” when demand increases. Amazon’s Whole Foods stores have become a testing ground for advancing this technique. Prices shown on electronic tags are tested, combined with discounts for Prime members, and relentlessly tweaked.

The potential damage to society from personalized pricing is significant, notes Maurice Stucke, a professor at the University of Tennessee. “It’s not just price discrimination, but also behavioral discrimination,” he says. “Getting people to buy things they might not have otherwise purchased, at the highest price they’re willing to pay.”

Amazon has plenty of options for this behavioral nudging, from listing a fake higher price and crossing it out to make it look like the customer is getting a deal, to its work on a facial recognition system using phone or computer cameras to authenticate purchases. With this tool, Amazon could theoretically read faces and increase prices when someone shows excitement about a product. Amazon has already licensed facial recognition software to local police units for criminal investigations, to outcry from privacy groups.

Then there’s Alexa, Amazon’s digital assistant, a powerful tool for manipulation. Alexa was designed to “be like the Star Trek computer,” said Paul Cutsinger, Amazon’s head of voice design education, at a developer conference earlier this year. Users can ask Alexa to play music and podcasts, answer questions, run health and wellness programs, set appointments, make purchases, even raise the temperature in the shower.

Psychologist Robert Epstein, who has pioneered research into search engine manipulation, has done preliminary studies on Alexa. “It looks like you can very easily impact the thinking and decision-making and purchases of people who are undecided,” Epstein says. “That unfortunately gives a small number of companies tremendous power to influence people without them being aware.” For example, Alexa can suggest a wine to go with the pizza you just ordered. It can also encourage you to set up a recurring purchase, the price of which may then go up based on Amazon’s list price.

The influence only increases as Alexa takes in more data. We know that Alexa is constantly watching and listening to users, transcribing what it hears and even transmitting some of that data back to a team of human listeners at Amazon, who “refine” the machine’s comprehension. The surveillance doesn’t only happen on Alexa, but in the smart home devices it integrates with, and on the website where Amazon tracks search and purchase activity. Amazon even has a Ring doorbell and in-home monitor, which sends information back to Amazon. There is no escape. “Devices all around us are watching everything we do, talking to each other, sharing data,” Epstein says. “We’re embedded in a surveillance network.”

EVEN AS IT’S INFLUENCING OUR BEHAVIOR, Amazon is transforming our physical world. José Holguín-Veras, a logistics and urban freight expert at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, estimates that in 2009, there was one daily internet-derived delivery for every 25 people. By 2017, he calculates, this had tripled. “The number of deliveries to households is now larger than the number of deliveries to commercial establishments,” Holguín-Veras says. “In skyscrapers in New York City where 5,000 people live, it’s 750 deliveries a day.”

Think of the difference between one trip to the grocery store for the week, and five or ten trips from the warehouse to your house. Our streets are too narrow and our traffic too plentiful to handle that additional traffic without crippling congestion. Plus, every idling car, and every extra delivery truck on the road, spews more carbon into the atmosphere. Our cities are not designed for the level of freight that instant delivery demands.

More deliveries also means more people staying indoors. “One thing I think about is how much we overlook the community and democracy value of running errands,” says Stacy Mitchell of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. “These exchanges—chatting with someone in line, bumping into a neighbor on the street, talking with the store owner—may not be all that significant personally. But this kind of interaction pays off for us collectively in ways we don’t think about or measure or account for in policy-making.”

In These Times asked Frank McAndrew of Knox College, who has researched social isolation, whether Amazon’s perfect efficiency could be alienating. He wasn’t ready to make a definitive statement but did see some red flags. “I do think we’re sort of wired to interact with real people in face-to-face situations,” McAndrew says. “When most of our interactions take place virtually, or with Alexa, it’s not going to be satisfying.”

FOR MOST OF OUR HISTORY, Americans didn’t require a personal digital assistant to answer our every whim. Why are we now reordering our social and economic lives, so one man can accumulate more money than anyone in the history of the planet?

One answer is that Amazon has paid as much attention to capturing government as it has to captivating customers. Amazon’s lobbying spending is among the highest of any company in America. After winning a nationwide procurement contract, over 1,500 cities and states can buy office items through the Amazon Business portal; a federal procurement platform is on the way. Amazon Web Services has the inside track on a $10 billion cloud contract to manage sensitive data for the Pentagon, something it already does for the CIA. That’s part of the reason why Amazon moved its second headquarters (after an absurd, game show-style bidding war that gave the company access to valuable data on hundreds of cities’ planning decisions) to a suburb of Washington, D.C., the seat of national power.

Making the directors of the regulatory state dependent on your services is a genius move. What political figure would dare crack down on the behavior of a trusted partner like Amazon?

In fact, Amazon has relied on government largesse since day one. No sales taxes for online purchases gave it a pricing advantage over other sellers (while a 2018 Supreme Court ruling changed that, the damage had been done). No carbon taxes helped Amazon build energy-intensive businesses dependent on fossil fuels for transportation and server farms. A lack of antitrust enforcement created a path for Amazon to super-size into an e-commerce monopoly. Weak federal labor rules let Amazon stamp out collective bargaining and rely on independent contractors. Mandatory arbitration locked third-party sellers inside Amazon’s private appeals process. Favorable tax law allowed Amazon to apply annual losses in previous years to its past two tax returns, paying no federal taxes on billions in income.

Of course, these rules helped all corporate giants and made executives filthy rich, often at the expense of workers. But Amazon tests the laissez-faire system in unique ways. In a future where Amazon broadens its control over our lives such that citizens have nowhere else to shop, businesses have nowhere else to sell, workers have nowhere else to toil, and governments have no other way to function, then who actually holds the power in our society? Avoiding that dark future requires leaders with the political will to stop it.

Elizabeth Warren’s plan to break up Amazon would rein in what she sees as unfair competition by preventing Amazon from selling products while hosting a website platform for other sellers. Warren also suggests splitting off Whole Foods and the online retailer Zappos, which Amazon bought in 2017 and 2009, respectively.

Fostering competition is a good start, but regulation must also prevent Amazon from bullying suppliers and partners. Lawmakers must force Amazon to pay for the externalities associated with its carbon-intensive delivery network. The company must pay a living wage to its workers, including its so-called independent contractors. It must be accountable to the legal system rather than a corporate-friendly arbitration process. It must not profit from spying on its customers.

If Amazon has caused this much upheaval today, when online shopping is still only 16 percent of retail sales, the future is limitless and grim. We have time to reverse this transfer of power and make it our world instead of Amazon’s. It’s an opportunity we cannot afford to squander.

Unrealistically Great Expectations

By Charles Hugh Smith

Source: Of Two Minds

Our expectations have continued ever higher even as the pie is shrinking..

Let’s see if we can tie together four social dynamics: the elite college admissions scandal, the decline in social mobility, the rising sense of entitlement and the unrealistically ‘great expectations’ of many Americans.

As many have noted, the nation’s financial and status rewards are increasingly flowing to the top 5%, what many call a winner-take-all or winner-take-most economy.

This is the primary source of widening wealth and income inequality: wealth and income are disproportionately accruing to the top slice of earners and owners of productive capital.

This concentration manifests in a broad-based decline in social mobility: it’s getting harder and harder to break into the narrow band (top 5%) who collects the lion’s share of the economy’s gains.

Historian Peter Turchin has identified the increasing burden of parasitic elites as one core cause of social and economic collapse. In Turchin’s reading, economies that can support a modest-sized class of parasitic elites buckle when the class of elites expecting a free pass to wealth and power expands faster than what the economy can support.

The same dynamic applies to productive elites: as I have often mentioned, graduating 1 millions STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) PhDs doesn’t magically guarantee 1 million jobs will be created for the graduates.

Such a costly and specialized education was once scarce, but now it’s relatively common, and this manifests in the tens of thousands of what I call academic ronin, i.e. PhDs without academic tenure or stable jobs in industry.

This glut is a global: I’ve known many people with PhDs from top universities in the developed world who have struggled to find a tenured professorship or a high-level research position anywhere in the world.

In other words, what was once a surefire ticket to status, security and superior pay is no longer surefire.

No wonder wealthy parents are so anxious to fast-track their non-superstar offspring by hook or by crook.

There is an even larger dynamic in play. As I explained here recently, the economic pie is shrinking, not just the pie of gains that can be distributed but the pie of opportunity.

Would parents and students be so anxious about their prospects if opportunities abounded for average students? The narrowing of opportunities to secure a stable career and livelihood is driving the frenzy to get into an elite university.

As everyone seeks an advantage, there’s a vast expansion of people with advanced diplomas: what was once relatively scarce (and thus valuable) is no longer scarce and therefore no longer very valuable.

The soaring cost of the middle-class membership basics–home ownership, healthcare and access to college–has drastically reduced the number of households who can afford these basics.

Two generations ago, just about any frugal working-class household with two wage-earners could save up a down payment for a modest home and later, save enough to put their children through the local state college.

Now, even two relatively well-paid wage earners in Left and Right Coast urban areas cannot afford to buy a house or put their kids through college. They are lucky to afford the rent, never mind buying a house.

As the number of upper-middle class slots declines, expectations have risen.This manifests in two ways: a rising sense of entitlement, which broadly speaking is the belief that the material security of middle class life should be available without great sacrifice.

The second manifestation is is higher expectations of material life in general: not only should we all have access to healthcare, college and home ownership, we also “deserve” to eat out every day, own luxury brand items, take resort vacations, and so on.

In a recent pre-recording conversation with a podcast host, we were talking about the number of average workers who think very little (apparently) of buying a $15 breakfast and/or a $20 lunch for themselves every day, plus an expensive coffee or beverage. This contrasts with the “old school” expectations which reserved lunches in restaurants for executives with expense accounts or The Boss. Everyone else filled a thermos with coffee at home and packed a brown bag lunch (or kau-kau tin in Hawaii).

From this perspective, $25 a day is $125 a week or $6,250 annually (a 50-week year). That’s $12,500 annually for a two wage-earner household. Five years of foregoing this luxury yields a nest egg of $62,500, a down payment for a $300,000 house, or the full cost of a four-year university education for two students who attend the local state university and who live at home.

(Sidebar note: a kind person gave us a $50 gift certificate to a popular casual-dining breakfast-lunch cafe. I reckoned we’d get a nice chunk of change after ordering two basic sandwiches and one beer. The $50 didn’t cover the three items, much less the tip. I nearly fell out of my chair. Over $50 for two sandwiches and a beer? And yet the place is jammed with people young and old, and I wondered: is everyone here earning $200,000+ annually, i.e. a top 5% income? If not, how can they afford such a costly luxury?)

As I noted earlier this month in the blog, the Federal Reserve’s obsession with generating a “wealth effect” by inflating bubbles in stocks and housing have enriched owners of capital at the expense of the young.

But even if we set aside the perverse and destructive impact of this disastrous policy, the economy is changing in structural ways. Scarcity value is becoming, well, scarcer. Global competition has reduced the scarcity value of education, ordinary labor and capital, and so the gains flowing to these has declined accordingly.

Yet our expectations have continued ever higher even as the pie is shrinking. Common sense suggests realigning expectations with a realistic appraisal of what’s possible and what sacrifices are necessary is a good first step.

Inventing the Future: The Collective Joy of Mark Fisher’s ‘k-punk’

By Michael Grasso

Source: We Are the Mutants

k-punk

By Mark Fisher

Foreword by Simon Reynolds, Edited by Darren Ambrose

Repeater Books, 2018

A little over two years ago, theorist and cultural critic Mark Fisher took his own life at the age of 48. I remember feeling numb at hearing the news; not out of sadness but more a sense of deja vu, of familiarity. I’d been through something similar already with David Foster Wallace’s suicide back in 2008; his Infinite Jest (1996) was one of the single most searing, searching moral indictments of the post-Cold War social and political order in the West, and a tremendously important work to me personally. Fisher toiled in very much the same fields in his writings. Both men had used their own struggles with depression (and in Wallace’s case, addiction) to fuel their insights into a world order that had run out of promise, of hope for the future. Wallace died two months before Barack Obama was elected, in the midst of the 2008 financial crisis; Fisher immediately after the election of Donald Trump. One American election offered (misplaced) hope, the other, a terminal kind of despair.

Over the past year or so I’ve also had the opportunity, while finishing my Master’s degree, to delve deeply into the work of cultural critic Walter Benjamin, who came to intellectual maturity in the Weimar Republic and found himself an exile with the rise of the Nazis in 1933. Like Wallace and Fisher, Benjamin used the cultural environment around him to help explain the world, to make sense of the turmoil that was roiling the once-orderly social order around him. Benjamin also killed himself, as he fled from the Nazi invasion of France in 1940 at the age of 48, just like Fisher. The parallels between all three men, to my mind, were uncanny. In the end, I feel the same thing got all three of these men: the encroaching feeling of dread at observing a world that had spun off its axis, beyond their ability to explain it.

I offer all this as a preface to my review of Mark Fisher’s collected online and unpublished writings, k-punk (Repeater Books, 2018), because I find myself thinking more often these days about the void of Fisher’s loss rather than the wealth of writings that he gave us while he was alive. And I feel like my despair essentially misunderstands what Mark Fisher was all about. The overwhelming feeling of most of the writings collected in k-punk is one of utter joy, whether it’s in celebrating a lost piece of media that Fisher wants us to know about, or his just and righteous delight in explaining exactly what late capitalism is doing to all of us.

A couple of years ago, my podcast partner Rob MacDougall and I had occasion to talk about the intellectual history of defining and preventing sexual harassment in the workplace for our podcast about WKRP in Cincinnati. And I’ll never forget the way he explained how clearly and uncompromisingly that defining a social problem can be the most important first step in combating it. He said, “Language is technology. Until you can name [something], you can’t get at it.” And I think that’s the legacy of Mark Fisher in a lot of ways. He gave us new terms—“pulp modernism,” “the precariat,” “hauntology,” “capitalist realism,” “acid communism”—that helped define not only our problems but our collective dreams for a better world. Like Benjamin before him, Fisher used his precise and profoundly moral observations of the world around him to give us a vocabulary to understand and express what is being done to us and how we can find our way out of it.

First things first: k-punk is a monster. Repeater Books has collected Fisher’s blog posts and unpublished writings in a massive 800-page tome. Given that the average length of one of these essays is about 3-4 pages, what you end up with is a bewilderingly encyclopedic collection of Fisher’s thoughts on seemingly everything. The conversion of once-hyperlink-laden web text to paper is sometimes jarring—the editor Darren Ambrose has done yeoman work in providing footnotes to mark where links to other bloggers and commenters once lay—but the reader almost never feels lost in figuring out what Fisher was trying to say. The foreword is by Fisher’s contemporary and friend, the music critic Simon Reynolds, whose seminal 2005 work on post-punk, Rip It Up and Start Again, is a favorite of mine. The same author’s 2011 Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past was, like Fisher’s work, a major inspiration for my own Master’s capstone project on nostalgia and its use in museums. Reynolds’ foreword is not only a heartfelt and deeply touching tribute to Fisher’s life and work, it also illustrates well the cultural milieu in which both men worked in the early part of this century. Getting to know someone better by reading their blog everyday is a deeply familiar mode to me and many members of my generation, and here Reynolds nails the somewhat uncanny feeling of getting to be best friends with someone you’ve only hung out with a few times in person. Probably it will be less strange for the generations who come after us. I do admit stifling a chuckle as one of the first essays in this paperback collection is a “tag five friends” meme; seeing such an essentially “online” phenomenon in print, in an esteemed cultural critic’s essay collection no less, would probably be considered “weird” in the Fisherian “weird/eerie” schema: an intruder from Outside whose alien presence inflects its surroundings.

In his foreword, Reynolds dubs Fisher a member of a disappearing breed: “the music critic as prophet.” Both Reynolds and Fisher came of age in the golden era of British publications like the NME, which treated its readers with a modicum of sophistication and intellectual respect. British music critics in the 1980s were never afraid to throw in references to contemporary political philosophers and cultural critics from the world of academia, nor were they reluctant to blur the lines between artist and critic. Fisher himself offers tribute to one of these writer-artists in “Choose Your Weapons,” an essay focusing on NME writer and Art of Noise member/ZTT Records co-founder Paul Morley, as well as his fellow NME writer Ian Penman. Reynolds sees Fisher as the clear heir to this type of rock journalist; Fisher even had his own musical group in the early 1990s, D-Generation, which peppered press releases and music with references to cultural theory.

As mentioned above and in my earlier piece on him, Fisher was never afraid to unearth a piece of forgotten media from his childhood or adolescence for examination in the cold light of our present late capitalism. His mourning for the loss of risk-taking on the part of the gatekeepers at public broadcasters such as the BBC is well-known. (I highly recommend the essay “Precarity and Paternalism” in k-punk for Fisher’s breathtaking rhetorical link between the blandness of pop culture today and the burning down of the public sphere under neoliberalism.) But what k-punk puts forth clearly (and Reynolds makes clear in his foreword) is that Fisher was never solely a backwards-looking critic. In these essays you can see him fully engaged in the contemporary cultural scene in a way that can sometimes get lost in his reputation as “the hauntology guy.” I found Fisher’s recuperation of Donnie Darko director Richard Kelly’s odd little Twilight Zone riff from 2009, The Box, to be downright essential in explaining why I liked it so much but couldn’t articulate why at the time. Ironically, Fisher avers that it is a rare piece of American hauntology (an aesthetic I’ve been desperately trying to quantify here at We Are the Mutants), with Kelly exploring the legacy of his NASA employee dad during NASA’s own final years of glory as a public agency (the late ’70s era of the Viking and Voyager probes) before the ultimately doomed Shuttle program. As someone who only gave the k-punk blog a cursory look prior to Fisher’s death, being far more familiar with his published writings, reading Fisher on the Christopher Nolan Batman trilogy or on contemporary television series that I watched from the beginning, like Breaking Bad and The Americans, hit me in that same Fisherian-weird way.

Even though the essays in the k-punk collection are organized by content type—reviews of books, music, television/film, political writings, interviews—it’s easy to note Fisher’s evolution as a writer, with each content area organized chronologically within. Perhaps this is only my prejudice, but I notice in the early years of Fisher’s k-punk posts a distinct anxiety of influence with older writers and theoreticians, out of which he eventually matures. His early-’00s work centers writers and thinkers like J.G. Ballard, Franz Kafka, Dennis Potter, even Freud and Spinoza. Slavoj Žižek also looms very large, probably for no other reason than that he was (and still is) one of the only voices engaging intelligently with the political impact of the pop culture detritus of late capitalism. But it’s in this occasional early tension with Žižek that you start to see Fisher make his own conclusions, state his own thoughts. It’s not necessarily that Fisher ever makes an explicit break with Žižek; it’s just that you see him mentioned less and less and, finally, not at all.

It was in music that Fisher saw the greatest potential for social and cultural revolution. It’s become a thoroughly lazy trope among armchair cultural critics to keep quoting that bit from Plato’s Republic about how changing a society’s music will change the society, but Fisher actually convinces the reader of that idea, in a profoundly vital and contemporary context. For Fisher, mod, glam, and to a certain extent punk all offered the working classes a chance to grab the same aristocratic glamor and glory to which the bourgeoisie had always had access. (Reading Fisher on the unearthly magical “glamour” of pop stars gets me thinking about Kieron Gillen’s “gods come to earth as pop stars” comic The Wicked + the Divine; I’d be shocked if Gillen wasn’t a k-punk reader from way back.) I personally find Fisher far stronger on post-punk. His multi-part examination of The Fall and Mark E. Smith is downright essential; I thought often while reading how much I wish Fisher could have read Richard McKenna’s Sapphire And Steel-referencing encomium to Smith. A pure love of Green Gartside of Scritti Politti and his dance-floor theoretics, so beloved by that very same theory-soaked 1980s NME, shines through in several k-punk essays. Fisher’s multiple essays on the goth aesthetic (and adjunct aesthetic movements like steampunk) are insightful, even as he holds goth at a bit of a remove as compared to post-punk and dance music. His essays on the Cure, Nick Cave, and specifically Siouxsie Sioux’s visual aesthetic from early swastika-armband-wearing punk provocateur to glittering Klimt spectacle on A Kiss in the Dreamhouse are particularly good.

And it’s here in Fisher’s music writing that we see yet another evolution, this time in three phases roughly analogous to the Marxist-Fichtean dialectic. Fisher begins with an arguably essentialist, archetypal, borderline Paglian view of the aristocratic charisma inherent in pop music; moves to a canny and earnest recognition of the purely proletarian qualities of post-punk and dance music (and the paradoxically populist power of the “public information” aesthetic of hauntological music); and then shifts to an eventual synthesis of these very different conceptions of music-as-liberation.

That synthesis was to be the topic of his next book, Acid Communism, the preface for which is included at the end of k-punk: Fisher was going to look back at the origin point for neoliberalism in the 1970s and pinpoint exactly where the workers’ movement and the left had begun to lose the battle for power. Through a re-examination of the 1960s New Left under thinkers such as Herbert Marcuse, Fisher locates the real revolutionary promise and potential in the bewildering flowering of popular culture that occurred in the ’60s, as well as the profound societal change that this revolution in culture propelled. “Mass culture—and music culture in particular—was a terrain of struggle rather than a dominion of capital,” Fisher notes. The true conflict of workers’ leftism vs. neoliberalism, Fisher argued, happened nearly a decade before neoliberalism’s origin point, in the struggle between the liberal Cold War orthodoxies in the West and the profoundly psychedelic movement of the youth rebelling against these staid establishment cultural tendencies. In America, of course, this series of youth movements became inexorably intertwined with resistance to the Vietnam War, perhaps to its detriment. Fisher posits instead a youth movement that worked against the assumptions of Cold War-era society on a much more elemental level. He finds much more interesting the movements where the left chafed against the High Cold War hegemony of labor-leftism in the West and indeed the very idea of work, and sees glimmers of his “acid communism” in social milieus as disparate as Paris in 1968, the British miners’ strike (aided by students) in 1972, the GM strike in Lordstown Ohio in 1972, and Bologna in 1977. The essential question asked in all these times and places: what if the revolution happens and we are in thrall to just another set of labor bureaucrats? One might answer that this actually happened with the ascension of the Baby Boomers to places of authority in the supposedly kinder, gentler, more “diverse” digital capitalism we live with today.

Obviously, virtually every bit of cultural writing that Fisher published was viewed through the prism of a leftist politics, but in the Politics and Interviews sections of k-punk, we get those politics unfiltered through any particular piece of pop culture. Here is where you see Fisher at his most passionate, his most personal, his most vital. Most important, in my mind, is his relentless insistence that capitalism kills both body and soul. While a Marxist theory of alienation is certainly nothing new, Fisher’s own personal experiences with being a member of the “precariat,” dealing with the peculiar doublethink of the purported “freedom” of the gig economy, demonstrates how the market hands us all slavery in the guise of self-actualization. And here is where Fisher’s writing intersects with his profound personal interest in public health, specifically mental health. Digital technology allows the gig worker to be relentlessly surveilled and ruthlessly “reviewed”; the disappearance of the old forms of authority and hierarchy in the workplace are distributed among one’s fellow consumers to create a web of virtual bureaucracy that creates constant cognitive dissonance and the distinct feeling that one is truly never off the job. From the ancient dream of never working to the modern reality of constantly working: Fisher thus asks us over and over if it’s any wonder we are all anxious and depressed?

It’s glaringly obvious stuff to most of us living in 2019, but again: Fisher’s moral clarity shines through and illuminates the darker corners of a world to which we’ve all slowly acquiesced. And yes, Mark Fisher did suffer from severe depression himself. One of the editorial decisions that I disagree with most is the stated decision to not include Fisher’s more “pessimistic” work from earlier in his career. Here is k-punk‘s editor Ambrose on this decision:

A very small number of early k-punk posts, e.g. on antinatalism, are excluded by virtue of the fact that they seemed wildly out of step with Mark’s overall theoretical and political development, and because they seemed to reflect a temporary enthusiasm for a dogmatic theoretical misanthropy he repudiated in his later writing and life.

You still see glimpses of this pessimism and near-nihilism in a few of the essays; a startlingly good review of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ where Fisher sees its neo-Gnostic underpinnings, or a deep intrigue with the antinatalist works of horror writer and philosopher Thomas Ligotti (who would find unexpected mass popularity with Nic Pizzolatto’s use of Ligotti in the first season of True Detective). But speaking as someone who suffers with mental illness and profound depression, let me make clear: it is absolutely reasonable to expect someone even as optimistic and positive as Fisher to occasionally look at the world with abject despair. Moreover, I believe it is more than merely reasonable, it’s necessary. To dispute or deny that anyone with a modicum of political awareness would not be occasionally nihilistically fucking depressed with the world as it is today seems a massive mistake to me.

Immediately before presenting the unfinished introduction to Acid Communism, we’re presented with two of Fisher’s most famous essays: his polemic against the contemporary left’s tendency towards ideological puritanism, “Exiting the Vampire Castle,” and his personal memoir of living (and working) with depression, “Good For Nothing.” No two pieces in this book depict the central contradictions and tensions of Fisher’s ethics and philosophy more clearly. “Vampire Castle” is, in my personal opinion, one of Fisher’s greatest missteps and the one piece of his writing where I most see a distressing tendency towards a lack of empathy for his comrades. In the essay, Fisher excoriates a certain faction of the left and its tendency to center “identity politics.” He further posits that these identity-based politics are a way in which the mechanisms of late capitalist control attempt to neuter and split the political left, a profoundly “individualistic” movement rather than one that builds cross-cultural solidarity. Fisher states that humorless scolds participating in “call-out culture” are preventing the left from building true power. Every time I go back to this essay, I initially find myself seeing some some modicum of logic in Fisher’s arguments. But then I remember how much of the modern capitalism that Fisher despised is literally built on the backs of genocide, racism, slavery, colonialism. I remember all of capitalism’s own constant essentializing and dividing of the proletariat, purely on the basis of identity, a superstructure that has systematically disenfranchised entire peoples on this globe, and ultimately I react with, “This is the kind of take that only a white guy from Britain could make.” It’s tone-deaf, destructive, and has given fuel to the worst strains of white exceptionalism and disdain for so-called “idpol” on the left in the past few years. I would argue that nothing good and quite a bit that is bad has come from it.

In fact, I wish someone would’ve told Mark how harmful this piece was. I have a feeling all it would have taken is one person—a woman, a person of color, an indigenous person, someone queer—to explain to him that while there should obviously be solidarity on the left, there are profound issues of historical materialism here that stretch back centuries, unfinished work that needs a profound upheaval and seizure of power from below (and yes, to some degree the anger and fury and the positive social knock-on effects of a “call-out culture”) to even begin to deal with restoratively. I want to believe he’d understand. It can be true that the capitalist powers-that-be love watching the left devour their own over issues that might seem personalized and “individual” to a white British man, but it can also be true that the profound historical injustices inflicted on colonized peoples the world over need to be centered in any revolutionary left solidarity. Both can be true.

And then you have “Good For Nothing,” an essay that I can say confidently has saved my life, maybe several times, since I first read it a few years ago. It is overflowing with empathy: for those of us hedged in by our class identities and made to feel inferior, uneducated, unworthy, a cog in a machine that only views us for how useful we can be to an employer or to the economy. It is a crisp distillation of every piece of personal writing Fisher ever wrote about the dehumanizing and alienating collective psychological effects of neoliberalism. Most importantly, it is a clarion call for solidarity:

For some time now, one of the most successful tactics of the ruling class has been responsibilisation. Each individual member of the subordinate class is encouraged into feeling that their poverty, lack of opportunities, or unemployment, is their fault and their fault alone. Individuals will blame themselves rather than social structures, which in any case they have been induced into believing do not really exist (they are just excuses, called upon by the weak)…

Collective depression is the result of the ruling class project of resubordination. For some time now, we have increasingly accepted the idea that we are not the kind of people who can act. This isn’t a failure of will any more than an individual depressed person can “snap themselves out of it” by “pulling their socks up.” The rebuilding of class consciousness is a formidable task indeed, one that cannot be achieved by calling upon ready-made solutions—but, in spite of what our collective depression tells us, it can be done. Inventing new forms of political involvement, reviving institutions that have become decadent, converting privatised disaffection into politicised anger: all of this can happen, and when it does, who knows what is possible?

This call for collective action on a political, economic, psychological, and even spiritual level is the voice of Mark Fisher’s that I remember and hold close to my heart every day. In every one of us there is a person worthy of respect and dignity, regardless of how “useful” we might be to a boss or a manager; in all of us a person who deserves not to live a life of misery, a person worthy of joy and music and glamour. That’s the Mark Fisher who throbs under the surfaces of nearly every one of these 800 pages. k-punk is a fitting tribute to a thinker who showed us the wonder in our past and the promise in our future, if we but remembered each other and not merely ourselves.

Michael Grasso is a Senior Editor at We Are the Mutants. He is a Bostonian, a museum professional, and a podcaster. You can read his thoughts on museums and more on Twitter at @MuseumMichael.

Why Are so Few Americans Able to Get Ahead?

By Charles Hugh Smith

Source: Of Two Minds

Our entire economy is characterized by cartel rentier skims, central-bank goosed asset bubbles and stagnating earned income for the bottom 90%.

Despite the rah-rah about the “ownership society” and the best economy ever, the sobering reality is very few Americans are able to get ahead, i.e. build real financial security via meaningful, secure assets which can be passed on to their children.

As I’ve often discussed here, only the top 10% of American households are getting ahead in both income and wealth, and most of the gains of these 12 million households are concentrated in the top 1% (1.2 million households). (see wealth chart below).

Why are so few Americans able to get ahead? there are three core reasons:

1. Earnings (wages and salaries) have not kept up with the rising cost of living.

2. The gains have flowed to capital, which is mostly owned by the top 10%, rather than to labor ((wages and salaries).

3. Our financialized economy incentivizes cartels and other rentier skims, i.e. structures that raise costs but don’t provide any additional value for the additional costs.

It’s instructive to compare today’s household with households a few generations ago. As recently as the early 1970s, 45 years ago, it was still possible for a single fulltime-earner to support the household and buy a home, which in 1973 cost around $30,000 (median house price, as per the St. Louis FRED database).

As recently as 20 years ago, in 1998, the median house price in the U.S. was about $150,000— still within reach of many two-earner households, even those with average jobs.

As the chart below shows, real median household income has only recently exceeded the 1998 level— and only by a meager $1,000 annually. If we use real-world inflation rather than the under-estimated official inflation, real income has plummeted by 10% or more in the past 20 years.

This reality is reflected in a new study of wages in Silicon Valley, which we might assume would keep up due to the higher value of the region’s output. The study found the wages of the bottom 90% declined when adjusted for inflation by as much as 14% over the past 20 years:

“The just-released report showed that wages for 90 percent of Silicon Valley workers (all levels of workers except for the top 10 percent)are lower now than they were 20 years ago, after adjusting for inflation. That’s in stark contrast to the 74 percent increase in overall per capita economic output in the Valley from 2001 to 2017.”

source: Why Silicon Valley Income Inequality Is Just a Preview of What’s to Come for the Rest of the U.S.

Meanwhile, the median house price has more than doubled to $325,000 while median household income has stagnated. Please note this price is not adjusted for inflation, like the median income chart. But if we take nominal household income in 1998 (around $40,000 annually) and compare it to nominal household income now in 2018 (around $60,000), that’s a 50% increase–far below the more than doubling of house prices.

To raise stagnant incomes, the Federal Reserve and other central banks have attempted to generate a wealth effect by boosting the valuations of risk-on assets such as stocks, bonds and commercial real estate. But the Fed et al. overlooked the fact that the vast majority of these assets are owned by the top 10%–and as noted above, the ownership of the top 10% is concentrated in the top 1% and .1%.

As a result, the vast majority of the wealth effect capital gains have flowed to the top 1%:

Lastly, the cartel structure of the U.S. economy has raised costs while providing no additional value. One example is higher education, a cartel that issues diplomas with diminishing economic value that now cost a fortune, a reality reflected in this chart of student loan debt, which simply didn’t exist a generation ago:

Our entire economy is characterized by cartel rentier skims, central-bank goosed asset bubbles and stagnating earned income for the bottom 90%. Given these realities, the bottom 90% are left with few pathways to get ahead in terms of financial security and building secure family wealth.