By Adam Mastroianni

Source: Experimental History

You may have noticed that every popular movie these days is a remake, reboot, sequel, spinoff, or cinematic universe expansion. In 2021, only one of the ten top-grossing films––the Ryan Reynolds vehicle Free Guy––was an original. There were only two originals in 2020’s top 10, and none at all in 2019.

People blame this trend on greedy movie studios or dumb moviegoers or competition from Netflix or humanity running out of ideas. Some say it’s a sign of the end of movies. Others claim there’s nothing new about this at all.

Some of these explanations are flat-out wrong; others may contain a nugget of truth. But all of them are incomplete, because this isn’t just happening in movies. In every corner of pop culture––movies, TV, music, books, and video games––a smaller and smaller cartel of superstars is claiming a larger and larger share of the market. What used to be winners-take-some has grown into winners-take-most and is now verging on winners-take-all. The (very silly) word for this oligopoly, like a monopoly but with a few players instead of just one.

I’m inherently skeptical of big claims about historical shifts. I recently published a paper showing that people overestimate how much public opinion has changed over the past 50 years, so naturally I’m on the lookout for similar biases here. But this shift is not an illusion. It’s big, it’s been going on for decades, and it’s happening everywhere you look. So let’s get to the bottom of it.

(Data and code available here.)

Movies

At the top of the box office charts, original films have gone extinct.

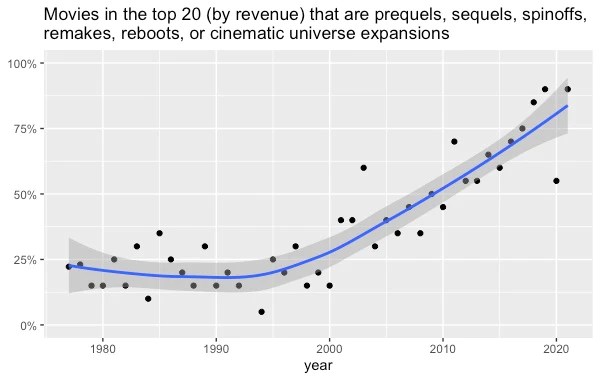

I looked at the 20 top-grossing movies going all the way back to 1977 (source), and I coded whether each was part of what film scholars call a “multiplicity”—sequels, prequels, franchises, spin-offs, cinematic universe expansions, etc. This required some judgment calls. Lots of movies are based on books and TV shows, but I only counted them as multiplicities if they were related to a previous movie. So 1990’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles doesn’t get coded as a multiplicity, but 1991’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze does, and so does the 2014 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles remake. I also probably missed a few multiplicities, especially in earlier decades, since sometimes it’s not obvious that a movie has some connection to an earlier movie.

Regardless, the shift is gigantic. Until the year 2000, about 25% of top-grossing movies were prequels, sequels, spinoffs, remakes, reboots, or cinematic universe expansions. Since 2010, it’s been over 50% ever year. In recent years, it’s been close to 100%.

Original movies just aren’t popular anymore, if they even get made in the first place.

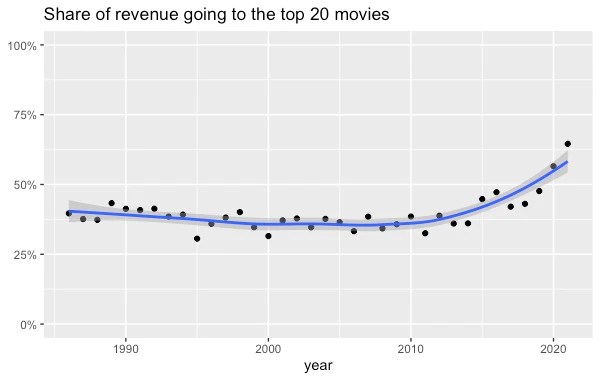

Top movies have also recently started taking a larger chunk of the market. I extracted the revenue of the top 20 movies and divided it by the total revenue of the top 200 movies, going all the way back to 1986 (source). The top 20 movies captured about 40% of all revenue until 2015, when they started gobbling up even more.

Television

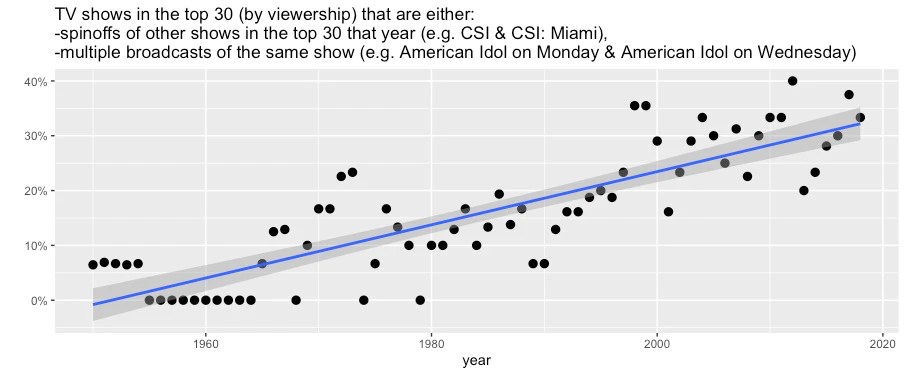

Thanks to cable and streaming, there’s way more stuff on TV today than there was 50 years ago. So it would make sense if a few shows ruled the early decades of TV, and now new shows constantly displace each other at the top of the viewership charts.

Instead, the opposite has happened. I pulled the top 30 most-viewed TV shows from 1950 to 2019 (source) and found that fewer and fewer franchises rule a larger and larger share of the airwaves. In fact, since 2000, about a third of the top 30 most-viewed shows are either spinoffs of other shows in the top 30 (e.g., CSI and CSI: Miami) or multiple broadcasts of the same show (e.g., American Idol on Monday and American Idol on Wednesday).

Two caveats to this data. First, I’m probably slightly undercounting multiplicities from earlier decades, where the connections between shows might be harder for a modern viewer like me to understand––maybe one guy hosted multiple different shows, for example. And second, the Nielsen ratings I’m using only recently started accurately measuring viewership on streaming platforms. But even in 2019, only 14% of viewing time was spent on streaming, so this data isn’t missing much.

Music

It used to be that a few hitmakers ruled the charts––The Beatles, The Eagles, Michael Jackson––while today it’s a free-for-all, right?

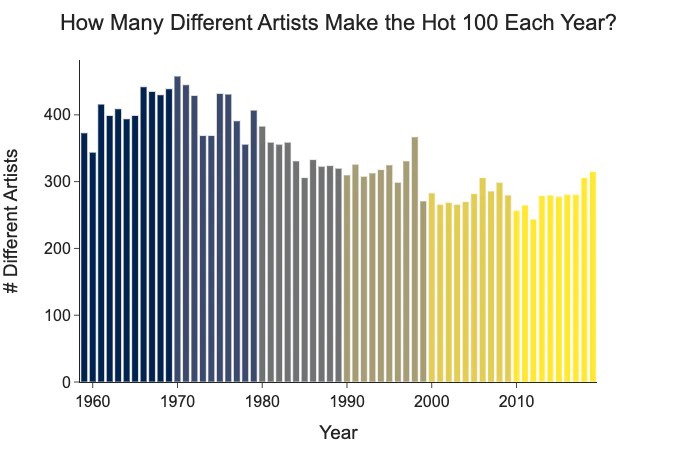

Nope. A data scientist named Azhad Syed has done the analysis, and he finds that the number of artists on the Billboard Hot 100 has been decreasing for decades.

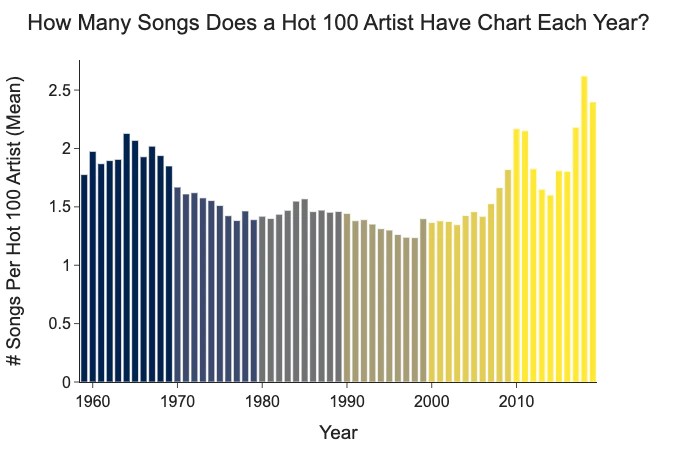

And since 2000, the number of hits per artist on the Hot 100 has been increasing.

(Azhad says he’s looking for a job––you should hire him!)

A smaller group of artists tops the charts, and they produce more of the chart-toppers. Music, too, has become an oligopoly.

Books

Literature feels like a different world than movies, TV, and music, and yet the trend is the same.

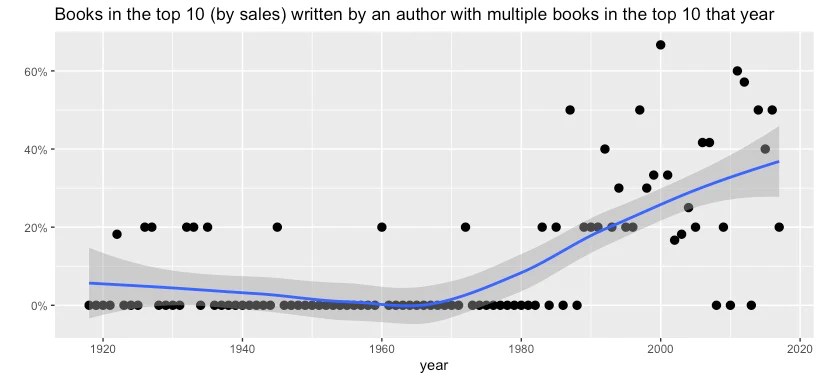

Using LiteraryHub’s list of the top 10 bestselling books for every year from 1919 to 2017, I found that the oligopoly has come to book publishing as well. There are a couple ways we can look at this. First, we can look at the percentage of repeat authors in the top 10––that is, the number of books in the top 10 that were written by an author with another book in the top 10.

It used to be pretty rare for one author to have multiple books in the top 10 in the same year. Since 1990, it’s happened almost every year. No author ever had three top 10 books in one year until Danielle Steel did it 1998. In 2011, John Grisham, Kathryn Stockett, and Stieg Larsson all had two chart-topping books each.

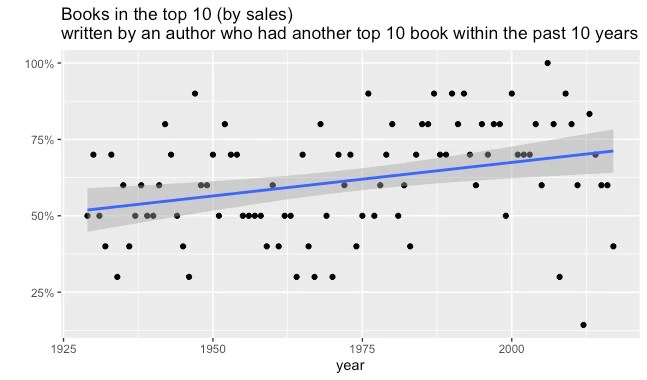

We can also look at the percentage of authors in the top 10 were already famous––say, they had a top 10 book within the past 10 years. That has increased over time, too.

In the 1950s, a little over half of the authors in the top 10 had been there before. These days, it’s closer to 75%.

Video games

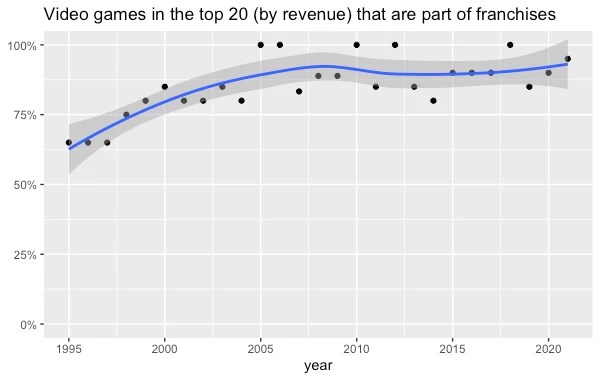

I tracked down the top 20 bestselling video games for each year from 1995 to 2021 (sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7) and coded whether each belongs to a preexisting video game franchise. (Some games, like Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, belong to franchises outside of video games. For these, I coded the first installment as originals and any subsequent installments as franchise games.)

The oligopoly rules video games too:

In the late 1990s, 75% or less of bestselling video games were franchise installments. Since 2005, it’s been above 75% every year, and sometimes it’s 100%. At the top of the charts, it’s all Mario, Zelda, Call of Duty, and Grand Theft Auto.

Why is this happening?

Any explanation for the rise of the pop oligopoly has to answer two questions: why have producers started producing more of the same thing, and why are consumers consuming it? I think the answers to the first question are invasion, consolidation, and innovation. I think the answer to the second question is proliferation.

Invasion

Software and the internet have made it easier than ever to create and publish content. Most of the stuff that random amateurs make is crap and nobody looks at it, but a tiny proportion gets really successful. This might make media giants choose to produce and promote stuff that independent weirdos never could, like an Avengers movie. This can’t explain why oligopolization started decades ago––YouTube only launched in 2005, for example, and most Americans didn’t have broadband until 2007––but it might explain why it’s accelerated and stuck around.

Consolidation

Big things like to eat, defeat, and outcompete smaller things. So over time, big things should get bigger and small things should die off. Indeed, movie studios, music labels, TV stations, and publishers of books and video games have all consolidated. Maybe it’s inevitable that major producers of culture will suck up or destroy everybody else, leaving nothing but superstars and blockbusters. Indeed, maybe cultural oligopoly is merely a transition state before we reach cultural monopoly.

Innovation

You may think there’s nothing left to discover in art forms as old as literature and music, and that they simply iterate as fashions change. But it took humans thousands of years to figure out how to create the illusion of depth in paintings. Novelists used to think that sentences had to be long and complicated until Hemingway came along, wrote some snappy prose, and changed everything. Even very old art forms, then, may have secrets left to discover. Maybe the biggest players in culture discovered some innovations that won them a permanent, first-mover chunk of market share. I can think of a few:

- In books: lightning-quick plots and chapter-ending cliffhangers. Nobody thinks The Da Vinci Code is high literature, but it’s a book that really really wants you to read it. And a lot of people did!

- In music: sampling. Musicians seem to sample more often these days. Now we not only remake songs; we franchise them too.

- In movies, TV, and video games: cinematic universes. Studios have finally figured out that once audiences fall in love with fictional worlds, they want to spend lots of time in them. Marvel, DC, and Star Wars are the most famous, but there are also smaller universe expansions like Better Call Saul and El Camino from Breaking Bad and The Many Saints of Newark from The Sopranos. Video game developers have understood this for even longer, which is why Mario does everything from playing tennis to driving go-karts to, you know, being a piece of paper.

Proliferation

Invasion, consolidation, and innovation can, I think, explain the pop oligopoly from the supply side. But all three require a willing audience. So why might people be more open to experiencing the same thing over and over again?

As options multiply, choosing gets harder. You can’t possibly evaluate everything, so you start relying on cues like “this movie has Tom Hanks in it” or “I liked Red Dead Redemption, so I’ll probably like Red Dead Redemption II,” which makes you less and less likely to pick something unfamiliar.

Another way to think about it: more opportunities means higher opportunity costs, which could lead to lower risk tolerance. When the only way to watch a movie is to go pick one of the seven playing at your local AMC, you might take a chance on something new. But when you’ve got a million movies to pick from, picking a safe, familiar option seems more sensible than gambling on an original.

This could be happening across all of culture at once. Movies don’t just compete with other movies. They compete with every other way of spending your time, and those ways are both infinite and increasing. There are now 60,000 free books on Project Gutenberg, Spotify says it has 78 million songs and 4 million podcast episodes, and humanity uploads 500 hours of video to YouTube every minute. So uh, yeah, the Tom Hanks movie sounds good.

What do we do about it?

Some may think that the rise of the pop oligopoly means the decline of quality. But the oligopoly can still make art: Red Dead Redemption II is a terrific game, “Blinding Lights” is a great song, and Toy Story 4 is a pretty good movie. And when you look back at popular stuff from a generation ago, there was plenty of dreck. We’ve forgotten the pulpy Westerns and insipid romances that made the bestseller lists while books like The Great Gatsby, Brave New World, and Animal Farm did not. American Idol is not so different from the televised talent shows of the 1950s. Popular culture has always been a mix of the brilliant and the banal, and nothing I’ve shown you suggests that the ratio has changed.

The problem isn’t that the mean has decreased. It’s that the variance has shrunk. Movies, TV, music, books, and video games should expand our consciousness, jumpstart our imaginations, and introduce us to new worlds and stories and feelings. They should alienate us sometimes, or make us mad, or make us think. But they can’t do any of that if they only feed us sequels and spinoffs. It’s like eating macaroni and cheese every single night forever: it may be comfortable, but eventually you’re going to get scurvy.

We haven’t fully reckoned with what the cultural oligopoly might be doing to us. How much does it stunt our imaginations to play the same video games we were playing 30 years ago? What message does it send that one of the most popular songs in the 2010s was about how a 1970s rock star was really cool? How much does it dull our ambitions to watch 2021’s The Matrix: Resurrections, where the most interesting scene is just Neo watching the original Matrix from 1999? How inspiring is it to watch tiny variations on the same police procedurals and reality shows year after year? My parents grew up with the first Star Wars movie, which had the audacity to create an entire universe. My niece and nephews are growing up with the ninth Star Wars movie, which aspires to move merchandise. Subsisting entirely on cultural comfort food cannot make us thoughtful, creative, or courageous.

Fortunately, there’s a cure for our cultural anemia. While the top of the charts has been oligopolized, the bottom remains a vibrant anarchy. There are weird books and funky movies and bangers from across the sea. Two of the most interesting video games of the past decade put you in the role of an immigration officer and an insurance claims adjuster. Every strange thing, wonderful and terrible, is available to you, but they’ll die out if you don’t nourish them with your attention. Finding them takes some foraging and digging, and then you’ll have to stomach some very odd, unfamiliar flavors. That’s good. Learning to like unfamiliar things is one of the noblest human pursuits; it builds our empathy for unfamiliar people. And it kindles that delicate, precious fire inside us––without it, we might as well be algorithms. Humankind does not live on bread alone, nor can our spirits long survive on a diet of reruns.