Source: The Hipcrime Vocab

It’s Time for Some Anti-Science Fiction

Why must positive depictions of the future always be dependent upon some sort of new technology?

Neal Stephenson is a very successful and well-known science fiction writer. He’s also very upset that the pace of technological innovation has seemingly slowed down and we seem to be unable to come up with truly transformative “big ideas” anymore. He believes this is the reason why we are so glum and pessimistic nowadays. Indeed, the science fiction genre, once identified with space exploration and utopias of post-scarcity and abundant leisure time, has come to be dominated by depictions of the future as a hellhole of extreme inequality, toxic environmental pollution, overcrowded cities, oppressive totalitarian governments, and overall political and social breakdown. Think of movies like The Hunger Games, Elysium, The Giver, and Snowpiercer.

This pessimism is destructive and corrosive, believes Stephenson. According to the BBC:

Acclaimed science-fiction writer Neal Stephenson saw this bleak trend in his own work, but didn’t give it much thought until he attended a conference on the future a couple years ago. At the time, Stephenson said that science fiction guides innovation because young readers later grow up to be scientists and engineers.

But fellow attendee Michael Crow, president of Arizona State University (ASU), “took a more sort of provocative stance, that science fiction actually needed to supply ideas that scientists and engineers could actually implement”, Stephenson says. “[He] basically told me that I needed to get off my duff and start writing science fiction in a more constructive and optimistic vein.”

“We want to create a more open, optimistic, ambitious and engaged conversation about the future,” project director Ed Finn says. According to his argument, negative visions of the future as perpetuated in pop culture are limiting people’s abilities to dream big or think outside the box. Science fiction, he says, should do more. “A good science fiction story can be very powerful,” Finn says. “It can inspire hundreds, thousands, millions of people to rally around something that they want to do.”

Basically, Stephenson wants to bring back the kind of science fiction that made us actually long for the future rather than dread it. Stephenson means to counter this techno-pessimism by inviting a number of well-known science fiction writers to come up with more positive, even utopian, visions of the future, where we once again come up with “big ideas” that inspire the scientists and engineers in their white labcoats. He apparently believes that it is the duty of science fiction authors to act as, in the words of one commentator, “the first draft of the future. ” Indeed, much of modern technology and space exploration was presaged by authors like H.G. Wells and Jules Verne. From the BBC article above, here are some of the positive future scenarios depicted in the book:

- Environmentalists fight to stop entrepreneurs from building the first extreme tourism destination hotel in Antarctica.

- People vie for citizenship on a near-zero-gravity moon of Mars, which has become a hub for innovation.

- Animal activists use drones to track elephant poachers.

- A crew crowd-funds a mission to the Moon to set up an autonomous 3D printing robot to create new building materials.

- A 20km tall tower spurs the US steel industry, sparks new methods of generating renewable energy and houses The First Bar in Space.

The whole idea behind Project Hieroglyph, as I understand it, is to depict more positive futures than the ones being depicted in current science fiction and media. That seems like a good idea. But my question is – why must these positive futures always involve more intensive application of technology? Why are we unable to envision a better future in any other way besides more technology, more machines, more inventions, more people, more economic growth, etc. Haven’t we already been down that road?

Or to put it another way, why must science fiction writers assume that more technological innovation will produce a better society when our modern society is the result of previous technological innovations, and is seen by many people as a dystopia (with many non-scientifically-minded people actually longing for a collapse of some sort)? Perhaps, to paraphrase former president Reagan, in the context of our current crisis, technology is not the solution to the problem, technology is the problem.

***

It’s worth pointing out that many of the increasingly dystopian elements of our present circumstances have been brought about by the application of technology.

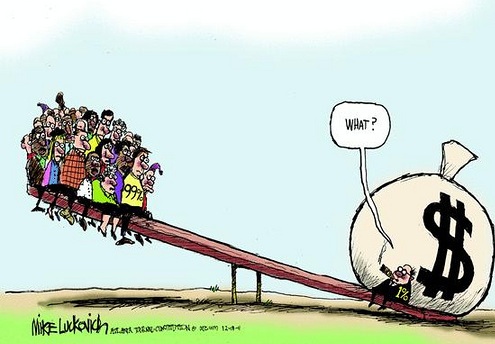

Economists have pinpointed technology as a key driver of inequality thanks to the hollowing out of the middle class due to the automation of routine tasks that underpinned the industrial/service economy leaving only high-end and low-end jobs remaining, as well as the “superstar effect” where a few well-paid superstars capture all the gains because technology allows them to everywhere at once. Fast supercomputers have allowed the rich to game the stock market casino where the average stock is now held for just fractions of a second, while global telecommunications has led to reassigning jobs anywhere in the world where the very cheapest workers can be found. America’s manufacturing jobs are now done by Chinese workers and its service jobs by Indian workers half a world away even as the old Industrial heartland looks suspiciously like what is depicted in The Hunger Games. Rather than a world of abundant leisure, stressed out workers take their laptops to the beach, fearful of losing their jobs if they don’t, while millions have given up even looking for work anymore. A permanently underemployed underclass distracts itself with Netflix, smartphones and computer games, and takes expensive drugs promoted by pharmaceutical companies to deal with their depression.

Global supply chains, supertankers, the “warehouse and wheels,” and online shopping have hollowed out local main street economies and led to monopolies in every industry across the board. Small family farmers have been kicked off the land worldwide and replaced by gargantuan, fossil-fuel powered agricultural factories owned by agribusinesses churning out bland processed food based around wheat, corn and soy causing soaring obesity rates worldwide and runaway population growth.

Banks have merged into just a handful of entities that are “too-big-to-fail” and send trillions around the world at the speed of light. Gains are privatized while loses and risk are socialized, and the public sphere is sold off to profiteers at fire sale prices. A small financial aristocracy controls the system and hamstrings the world with debt. Just eighty people control as much wealth as half of the planet’s population, and in the world’s biggest economy just three people gain as much income as half the workforce. There are now more prisoners in America than farmers.

A now global trans-national elite of owner-oligarchs criss-crosses the world in Gulfsteam jets and million-dollar yachts and hides their money in offshore accounts beyond the reach of increasingly impotent national governments, while smaller local governments can’t keep potholes filled, streets plowed and streetlights on for ordinary citizens. Many of the world’s great cities have become “elite citadels” making it impossible for regular citizens to live there. This elite controls bond markets, funds political campaigns and owns and controls a monopolized media that normalizes this state of affairs using sophisticated propaganda tools enhanced by cutting-edge psychological research enabled by MRI scanners. The media is controlled by a small handful of corporations and panders to the lowest common demonstrator while keeping people in a constant state of fear and panic. Advertising preys on our insecurities and desire for status to make us buy more, enabled by abundant credit. The Internet, once the hope for a more democratic future, has ended up as shopping mall, entertainment delivery system and spying/tracking system rather than a force for democracy and revolution.

Security cameras peer at us from every streetcorner and store counter and shocking revelations about the power and reach of the national security state that are as fantastic as anything dreamed up by dystopian science fiction writers have become so commonplace that people hardly notice anymore. Anonymous people in gridded glass office towers read our every email, listen to our every phone call and track our every move using our cell phones. New technology promises “facial recognition” and “smart” technology promoted by corporations promises to track and permanently record literally every move you make.

Remote-control drones patrol the skies of global conflict zones and vaporize people half a world away without their pilots ever seeing their faces. High-tech fighter jets allow us to “cleanly” drop bombs without the messiness of a real war. Private mercenaries are a burgeoning industry and global arms sales continue to increase even in a stagnant global economy with arms companies often selling to both sides. By some accounts one in ten Americans is employed in some sort of “guard labor,” that is, keeping their fellow citizens in line. The number of failed states continues to increase in the Middle East and Africa and citizens in democracies are marching in the streets.

Not that there’s nothing for the national security state to fear after all – technology has enabled individual terrorists and non-state actors to produce devastating weapons capable of destroying economies and killing thousands as 9-11 demonstrated. A single “superempowered” individual can kill millions with a nuclear bomb the size of a suitcase or an engineered virus or other bioterrorism weapon. The latest concern is “cyberwarfare” which could destroy the technological infrastructure we are now utterly dependent upon and kill millions. “Non-state actors” can wreak as much havoc as armies thanks to modern technology, and there are a lot of disgruntled people out there.

And then there is the environmental devastation, of which climate change is the most overwhelming, but includes everything from burned down Amazonian rainforest, to polluted mangroves in Thailand, to collapased fish stocks, dissolving coral reefs and oceans full of jellyfish. Half the world’s terrestrial biodiversity has been eliminated in the past fifty years and we’ve lost so much polar ice that earth’s gravity is measurably affected. In China, the world’s economic success story, the haze is so thick that people can’t see the tops of the skyscrapers they already have and there are “cancer villages.” The skies may be a bit clearer in America thanks to deindustrialization, but things like drought in the Southwest and increasinginly powerful hurricanes are reminders that no one is immune. Entire countries and major cities look to be submerged under rising oceans and the first climate refugees are already on the move from places like Africa and Southeast Asia leading to anti-immigrant backlash in developed countries.

This is not some future dystopia, by the way, this is where technology has us led right now. Today. Current headlines. Maybe the reason that dystopias are so popular is because that seems to be where technology had led us here in the first decade of the twenty-first century. I’m skeptical that Project Hieroglyph and it’s fostering of “big ideas” will do much to change that.

Thus my fundamental question is, given the above, why is it always assumed that the path to utopia goes through a widespread deployment of even more innovation and technology? Is it realistic to believe that colonies on Mars, drones, intelligent robots, skyscrapers and space elevators will solve any of this?

I’ve written before about the fact that the technology we already have in our possession today was expected to deliver a utopia by numerous writers and thinkers of the past. “The coming of the wireless era will make war impossible, because it will make war ridiculous,” declared Marconi in 1912. HG Wells, a committed socialist who lived during perhaps the greatest period of invention before or since (railroads, harnessing of electricity, radio communication, internal combustion engines, powered flight, antibiotics), very frequently depicted utopian societies brought about through the applications of greater technology. Science fiction authors still seem to conceive utopias as being exclusively brought about by “technological progress.” But given hindsight, is that realistic anymore?

Maybe it’s time for some anti-science fiction.

***

The classic example of this is William Morris’ utopian novel News From Nowhere.

Morris was a key figure in the Arts and Crafts movement, which was a reaction to the factory-based mass production and subsequent deskilling of the workforce. People no longer collectively made the world of goods and buildings around them, rather they were now made by a small amount of people using deskilled, alienated labor in giant factories with the profits accruing to a tiny handful of capitalist owners. Morris wanted another way.

In Morris’ future London there are very little in the way of centralized institutions. People work when they want to and do what they want to. Money is not used. Life is lived leisurely pace. Writing during the transformative changes of the Industrial Revolution, Morris’ London looks less like a World’s Fair and more like a lost bucolic pastoral London that had long since vanished under the smoke of factories. Technology plays a very small role yet people are much happier.

Morris’ work was written partially in response to a book entitled Looking Backward by Edward Bellamy, which was extraordinarily popular in the late nineteenth century, but almost forgotten today. Bellamy’s year 2000 utopia had the means of production brought under centralized control, with people serving time in an “industrial army” for twenty years and then retiring to a life of leisure and material abundance brought about by production for use rather than capitalist profit.

Morris still felt that this subordinated workers to machines rather than depicting a society for the maximization of human well-being, including work. Here is Morris in a speech:

“Before I leave this matter of the surroundings of life, I wish to meet a possible objection. I have spoken of machinery being used freely for releasing people from the more mechanical and repulsive part of necessary labour; it is the allowing of machines to be our masters and not our servants that so injures the beauty of life nowadays. And, again, that leads me to my last claim, which is that the material surroundings of my life should be pleasant, generous, and beautiful; that I know is a large claim, but this I will say about it, that if it cannot be satisfied, if every civilised community cannot provide such surroundings for all its members, I do not want the world to go on.”

Morris’ book shows that utopias need not be high-tech. It also shows that real utopias are brought about by the underlying philosophy of a society and its corresponding social relations. It seems to me like Stephenson’s utopias are all predicated on the continuation of the philosophy and social relations of our current society – more growth, more technology, faster innovation, more debt, corporate control, trickle-down economics, private property, absentee ownership, anarchic markets, autonomous utility-maximizing consumers, etc. It is yoked to our ideas of “progress” as simply an application of more and faster technology.

By contrast, Morris’ utopia has the technological level we would associate with a “dystopian” post collapse society, yet everyone seems a whole lot happier.

***

Now I don’t mean to suggest that any utopia should necessarily be a place where we have reverted to some sort pre-industrial level of technology. We don’t need to depict utopias as living like the Amish (although that would be an interesting avenue of exploration). I merely wish to point out that a future utopia need not be exclusively the domain of science fiction authors, and need not be predicated by some sort of new wonder technology or space exploration. For example, in an article entitled Is It Possible to Imagine Utopia Anymore? the author writes:

Recently, though, we may have finally hit Peak Dystopia…All of which suggests there might be an opening for a return to Utopian novels — if such a thing as “Utopian novels” actually existed anymore…In college, as part of a history class, I read Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backwards, a Utopian science-fiction novel published in 1888. The book — an enormous success in its time, nearly as big as Uncle Tom’s Cabin — is interesting now less as literature than as a historical document, and it’s certainly telling that, in the midst of the industrial revolution, a novel promising a future socialist landscape of increased equality and reduced labor so gripped the popular imagination. We might compare Bellamy’s book to current visions of Utopia if I could recall even a single Utopian novel or film from the past five years. Or ten years. Or 20. Wikipedia lists dozens of contemporary dystopian films and novels, yet the most recent entry in its rather sparse “List of Utopian Novels” is Island by Aldous Huxley, published in 1962*. The closest thing to a recent Utopian film I can think of is Spike Jonze’s Her, though that vision of the future — one in which human attachment to sentient computers might become something close to meaningful — hardly seems like a fate we should collectively strive for, but rather one we might all be resigned to placidly accept

Many serious contemporary authors have tackled dystopia: David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, Gary Shteyngart’s Super Sad True Love Story, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and so on. But the closest thing we have to a contemporary Utopian novel is what we could call the retropia: books like Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue (about a funky throwback Oakland record store) or Jonathan Lethem’s Fortress of Solitude (about 1970s Brooklyn) that fondly recall a bygone era, by way of illustrating what we’ve lost since — “the lost glories of a vanished world,” as Chabon puts it. Lethem’s more recent Dissident Gardens is also concerned with utopia, but mostly in so far as it gently needles the revolutionaries of yesteryear.

Indeed, the closest things we have to utopias on TV today are shows like Mad Men which take place during the era when Star Trek was on TV rather than a utopia inspired by Star Trek itself. For many Americans, their version of utopia is not in the future but in the past – the 1950’s era of widespread prosperity, full employment, single-earner households, more leisure, guaranteed pensions, social mobility, inexpensive housing, wide open roads and spaces, and increasing living standards. As this article points out:

When I first heard about the project, my cynical heart responded skeptically. After all, much of the Golden Age science fiction Stephenson fondly remembers was written in an era when, for all its substantial problems, the U.S. enjoyed a greater degree of democratic consensus. Today, Congress can barely pass a budget, let alone agree on collective investments.

If someone asked me to depict a more positive future than the one we have, deploying more technology is just about the last thing I would do to bring it about. In fact, the future I would depict would almost certainly include less technology, or rather technology playing a smaller role in our lives. I would focus more on social relations that would make us be happy to be alive, where we eat good food, spend time doing what we want instead of what we’re forced to, and don’t have to be medicated just to make it through another day in our high-pressure classrooms and cubicles. I might even depict a future with no television inspired by Jerry Mander’s 1978 treatise Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television (hey, remember this is fiction after all!)

Rather it would depict different political, economic and social relations first, with new technology playing only a supporting, not a starring role. Organizing society around the needs of productive enterprise, growth and profits (and nothing else) is the reason, I believe, why we are feeling so depressed about the future that dystopias resonate more with a demoralized general public who rolls their collective eyes at the exhortations of science fiction writers with an agenda**. The problem of science fiction is it’s single-minded conflagration of technology with progress.

Personally my utopia would be something more like life on the Greek island of Ikaria*** according to this article from The New York Times (which reads an awful lot like News from Nowhere):

Seeking to learn more about the island’s reputation for long-lived residents, I called on Dr. Ilias Leriadis, one of Ikaria’s few physicians, in 2009. On an outdoor patio at his weekend house, he set a table with Kalamata olives, hummus, heavy Ikarian bread and wine. “People stay up late here,” Leriadis said. “We wake up late and always take naps. I don’t even open my office until 11 a.m. because no one comes before then.” He took a sip of his wine. “Have you noticed that no one wears a watch here? No clock is working correctly. When you invite someone to lunch, they might come at 10 a.m. or 6 p.m. We simply don’t care about the clock here.”

Pointing across the Aegean toward the neighboring island of Samos, he said: “Just 15 kilometers over there is a completely different world. There they are much more developed. There are high-rises and resorts and homes worth a million euros. In Samos, they care about money. Here, we don’t. For the many religious and cultural holidays, people pool their money and buy food and wine. If there is money left over, they give it to the poor. It’s not a ‘me’ place. It’s an ‘us’ place.”

Ikaria’s unusual past may explain its communal inclinations. The strong winds that buffet the island — mentioned in the “Iliad” — and the lack of natural harbors kept it outside the main shipping lanes for most of its history. This forced Ikaria to be self-sufficient. Then in the late 1940s, after the Greek Civil War, the government exiled thousands of Communists and radicals to the island. Nearly 40 percent of adults, many of them disillusioned with the high unemployment rate and the dwindling trickle of resources from Athens, still vote for the local Communist Party. About 75 percent of the population on Ikaria is under 65. The youngest adults, many of whom come home after college, often live in their parents’ home. They typically have to cobble together a living through small jobs and family support.

Leriadis also talked about local “mountain tea,” made from dried herbs endemic to the island, which is enjoyed as an end-of-the-day cocktail. He mentioned wild marjoram, sage (flaskomilia), a type of mint tea (fliskouni), rosemary and a drink made from boiling dandelion leaves and adding a little lemon. “People here think they’re drinking a comforting beverage, but they all double as medicine,” Leriadis said. Honey, too, is treated as a panacea. “They have types of honey here you won’t see anyplace else in the world,” he said. “They use it for everything from treating wounds to curing hangovers, or for treating influenza. Old people here will start their day with a spoonful of honey. They take it like medicine.”

Over the span of the next three days, I met some of Leriadis’s patients. In the area known as Raches, I met 20 people over 90 and one who claimed to be 104. I spoke to a 95-year-old man who still played the violin and a 98-year-old woman who ran a small hotel and played poker for money on the weekend.

On a trip the year before, I visited a slate-roofed house built into the slope at the top of a hill. I had come here after hearing of a couple who had been married for more than 75 years. Thanasis and Eirini Karimalis both came to the door, clapped their hands at the thrill of having a visitor and waved me in. They each stood maybe five feet tall. He wore a shapeless cotton shirt and a battered baseball cap, and she wore a housedress with her hair in a bun. Inside, there was a table, a medieval-looking fireplace heating a blackened pot, a nook of a closet that held one woolen suit coat, and fading black-and-white photographs of forebears on a soot-stained wall. The place was warm and cozy. “Sit down,” Eirini commanded. She hadn’t even asked my name or business but was already setting out teacups and a plate of cookies. Meanwhile, Thanasis scooted back and forth across the house with nervous energy, tidying up.

The couple were born in a nearby village, they told me. They married in their early 20s and raised five children on Thanasis’s pay as a lumberjack. Like that of almost all of Ikaria’s traditional folk, their daily routine unfolded much the way Leriadis had described it: Wake naturally, work in the garden, have a late lunch, take a nap. At sunset, they either visited neighbors or neighbors visited them. Their diet was also typical: a breakfast of goat’s milk, wine, sage tea or coffee, honey and bread. Lunch was almost always beans (lentils, garbanzos), potatoes, greens (fennel, dandelion or a spinachlike green called horta) and whatever seasonal vegetables their garden produced; dinner was bread and goat’s milk. At Christmas and Easter, they would slaughter the family pig and enjoy small portions of larded pork for the next several months.

During a tour of their property, Thanasis and Eirini introduced their pigs to me by name. Just after sunset, after we returned to their home to have some tea, another old couple walked in, carrying a glass amphora of homemade wine. The four nonagenarians cheek-kissed one another heartily and settled in around the table. They gossiped, drank wine and occasionally erupted into laughter.

No robot babysitters or mile-high skyscrapers required.

* No mention of Ernest Callenbach’s Ecotopia published in 1975?

** ASU is steeped in Department of Defense funding and DARPA (The Defense Research Projects Agency) was present at a conference about the book entitled “Can We Imagine Our Way to a Better Future?” held in Washington D.C. I’m guessing the event did not take place in the more run-down parts of the city. Cui Bono?

***Ironically, Icaria was used as the name of a utopian science fiction novel, Voyage to Icaria, and inspired an actual utopian community.