By Dr. Nicholas Partyka

Source: The Hampton Institute

When politicians talk, one of the recurring themes about which they spew platitudes is the economy. It would be the subject of another essay to unpack what is meant by “the economy” when politicians and other capitalist elements use that term. This aside, in discussing the economy there is a phrase that politicians use with such alacrity that it has become trite. This phrase is, “middle class”. Politicians, pundits, and social commentators deploy this term in many contexts, but almost always appealing to its ubiquity of membership, critical role in democracy, and moral virtue in their speeches. These constant references to the middle class in the popular political discourse have rendered this term impenetrably vague. If we listen to politicians then one would be led to believe that most Americans are members of this middle class, whose health and prosperity the politicians never tire of proclaiming as their highest priority. Speeches are one thing, reality another. Let us interrogate this concept of the “middle class”, and see what to make of this notion that plays such a prominent role in American political discourse on the economy.

With an election year looming, and a Presidential election at that, with their seemingly always lengthening election cycle, the phrase “middle class” will only be heard more and more frequently from now until after November 2016. The President’s recent invocation of the phrase “middle class economics” is only the latest salvo between the two dominant capitalist political parties, as they try to position themselves in the public’s mind as the true defender of – the almost apotheosized- middle class. Candidates and their supporters will be arguing more and more vigorously about which party, or which policies, will do more to help this middle class. About the only thing that candidates from both parties will agree on is that the middle class is in trouble, and that economic policies should be designed which maximally promote the welfare of this class. The two major political parties in this country have divergent views about what kinds of policies best aid this alleged middle class. However, both parties are attempting to win votes by claiming to be champions of the middle class, a class with which a great many Americans still continue to identify themselves.

We’re going to explore two distinct, but interrelated questions in what follows. First, we’ll want to know, Who and how many, people are middle class? Second, we’ll want to ask, What does it mean to be middle class? The answers to these questions will likely have to be made relative to particular societies at particular times; though some generalization is possible. To begin we’ll look at what it has meant historically to be middle class. Then we’ll look more in depth into the meaning of being middle class in the contemporary American context. What we will find is a great deal more confusion and ambiguity about this notion of a “middle class”. So much so that we should start to wonder if this notion retains any usefulness.

The Middle Classes, Historically

For most of history being middle class simply meant occupying, however tenuously, a social status that was between that of a slave and that of a noble. Basically, the middle class was composed of everyone who was not technically a chattel slave, and lacking the noble pedigree of a true aristocrat. In most societies of the ancient world this simple definition would indeed make most people middle class. However, this understanding glosses over the highly variegated nature of socio-economic positions possible between technical chattel slavery and blue-blooded nobility. For instance, debt bondage and serfdom, both forms of un-free labour, would not cause one to be dropped from the middle class on this accounting. For example, in the ancient world slaves were often employed as overseers, that is in a management capacity. It would not have been uncommon for slave overseers to sometimes direct the labour of technically free men.

We can see in certain socio-political cleavages that splits have occurred in many contexts between the lower ranks of these middle classes and the higher elements of this class. Middle classes have struggled against entrenched aristocracy and nobility at many points in history for social advancement and political inclusion. However, almost always, in the critical moment, the higher elements of these middle classes would betray the interests of the lower elements, whose bodies, blood and ballots had been used to gain them inclusion. Marx would come to call these “higher elements” of the middle classes petit-bourgeoisie, signifying the much greater material, and indeed much more importantly, aspirational affinity with the bourgeoisie than the proletariat.

Two examples will suffice here. In ancient Greece we see the demos, or “the people” engaging in political struggle for inclusion in the political life of the polis. But who is this demos? First, Greeks used the word demos in two distinct ways. In one sense, we might call the wide sense, it meant the whole citizen body of city-state in general. In the narrow sense, on the other hand, the demos meant the ‘common people’, the ‘lower classes’, the aporoi, the propertyless. This group included a very wide range of socio-economic and political situations, and certainly contained an upper and lower group. The main cleavage within the ranks of the demos is between the better off elements and those struggling to get by. It goes without saying that slaves would not be counted among the demos. Those who are struggling are more, or in worst case entirely, dependent on others for their livelihood. The Greeks called Thetes and Banausoi. The former we might call day-labourers or wage earners, the latter we could translate loosely as artisans. These were the lowest two of Solon’s five social classes, and while not slaves, were subject to various kinds of forced labour. Though some artisans and merchants could be quite wealthy, most were not. Most merchants, as opposed to retailers, though were likely to be foreigners, and thus not eligible for citizenship.

When we focus on the internal political conflicts of the Greek polis of the Classical period (roughly the 5th and 4th centuries BC), what we see is a struggle over citizenship, that is over access to political participation in government. While the socio-economic and political realities of the ancient world are complex, in the main the conflicts were between an urban middle class of mainly artisans and middling farmers on the one hand, and the traditional land-owning oligarchy which monopolized political power on the other.[1] The political struggles over demokratia in this period revolved mainly around whether or not the banausoi and thetes should be given citizenship rights. Chiefly important among the rights of citizens were the right to vote in the Assembly, to hold public office, the serve as a juror in the dikasteria, to bring matters before the courts; at Athens in particular, citizens would be entitled to receive a share in any disbursement of the polis‘s dividends from the proceeds of the Laurium silver mines.

The demos was the main agent of social change in the ancient Greek polis, the traditional aristocracy certainly saw it this way. They saw “middle class” elements as being too politically ambitious, which is in part why they deploy the term pejoratively. By “middle class elements” the traditional aristocracy would have lumped together both very wealthy artisans, and much more humble enterprises, all of whom were united in not being aristocrats by blood lineage. Wealthy merchants and artisans might themselves employ slaves both for carrying out production, as well as the overseeing of this work, but they lacked the “best” kind of background. This made them unsuitable for political participation in the eyes of established elites. Smaller artisans and merchants, who didn’t have exorbitant wealth to recommend them, would have been thought only the more unsuited to political life.

All of the main institutions of Classical Greek demokratia were devices designed to help poor and working-class free men defend themselves from the depredations of their richer counterparts. Rule by majority vote in an Assembly, ekklesia, open to all citizens; freedom of speech, parrhesia, in the assembly; large popular courts of law, dikasteria, composed of fellow citizens; rule of law, isonomia, as passed by the Assembly and administered in the courts; the belief that political power should be scrutinized, subject to euthyna, are all practices that helped the aporoi defend their highly precarious social position from the predatory behavior of wealthy citizens. As one eminent scholar describes, “Since the majority of citizens everywhere owned little or no property, the propertied class complained that demokratia was the rule of demos in the narrower sense and in effect the domination of the poor over the rich.”[2]

In the ancient Greek polis political participation was usually restricted to those native adult men who could meet a certain property qualification. In the main, in order to be a citizen one had to possess enough wealth to afford to outfit themselves with the hoplite panopoly. This was the complete set of armaments associated with the heavy armed infantry. If one could afford to buy one’s own armor, and afford the leisure time to learn to fight as part of a phalanx formation, then one was considered worthy to participate in the political life of the polis. The idea being that if one was wealthy enough to afford the hoplite panopoly then one had enough of a stake in the success and survival of the polis to be entitled to a role in the government of the city-state. Those “old money” and nouveau riche aristocrats who were wealthy enough could afford to outfit themselves with horses as well as more ornate armor and weapons, and thus the traditional prestige associated with the cavalry. The question of democracy in the ancient Greek world, was thus a struggle over the inclusion of those who could not afford the traditional citizenship qualification based on the connection of wealth and military service, and who because they were not slaves could make legitimate claims to be entitled to such inclusion.

Renaissance Italy serves as another great example. In the rise of the classic northern Italian city-state podestaral form of communal government there was employed in the popular political discourse a term, the popolo. Loosely translated, it means the people. However, once again we’ll see that this notion of the people actually covers over a major divergence within between well-off members and working-class members. As one scholar claims, “When, therefore, the long and venomous struggle broke out between the popolo (the “people”) and the nobility, the popular movement drew its force and numbers from the middle classes, not from the poor, the day labourers, or the unskilled”.[3]

The political conflict in 13th century northern Italian city-states was, much like in the ancient Greek world, fundamentally about participation. Beginning in the 12th century, a political conflict between church and secular authorities saw the rise of communal governments in all the major Renaissance city-states in northern Italy. At the time, this form of government was identified with the self-government of local magnates and aristocrats instead of more alien authorities imposed by church leaders in Rome. In this early phase of commune government, “The nobility dominated the consulate, manipulated the general assembly, and ruled the city, except where the emperor successfully intervened, as at Vicenza, Siena, and Volterra, or where the political power of the Bishop persisted.”[4]

It was against this restricted form of government that the political forces of the popolo were arrayed in the 13th century. By organizing for combat against the military forces of the nobility, the popolo was able to seize power in the commune and change the structure of commune government, in that it was able to secure more participation for those in its ranks; or more correctly, some of those in its ranks. The popolo, much like the demos, was a class composed of better off artisans, tradesman, merchants, et cetera. It was a class of persons who had to work for a living, that is they had to do physical labour themselves to achieve their subsistence. These people were free, in that they were not slaves or serfs, but were not aristocrats, they did not possess the right kind of lineage. Political participation was at this time still restricted to those who did have the proper kind of aristocratic genealogy.

Much as in the case of the ancient Greek world, the main political cleavage in the Renaissance northern Italian city-state between the popolo and nobilitas largely concerned the way individuals made a living. Nobles owned large landed estates, and derived their wealth and status from being able to control the labour of others, i.e. vassals and serfs. Those who were not aristocrats could be wealthy, could own land, but typically had to work themselves. That is, the typical member of the popolo could not control the labour of others to the same extent that a noble could. The political conflicts of the 13th century were not simplistic conflicts between land owners and merchants, the reality was much more complicated than that.

Both popolo and nobilitas would be distinguished from a day-labourer in that they would be considered independent in the right sort of way, they would be considered the people who had real freedom. What distinguishes the position of the poorest classes is that they are dependent on others for their livelihood. Thus, for example, the serf is dependent on the lord, the tenant farmer on the land-owner, and the day-labourer on the employer who pays him. These kinds of people would have been considered not really free in the right way, especially politically. Though all God’s children would have been understood to be free, some were not considered free enough to be worthy of inclusion in government.

In what would become an unfortunate recurring tendency, once the leading – i.e. the wealthiest- elements in the “middle class”, the popolo, achieved inclusion in communal government, they allied with the old aristocracy and turned against the lower, more ‘middling’ elements in the popolo to suppress their continued agitations for further liberalization of political participation. Thus, as one scholar puts it,

“Up to about the middle of the thirteenth century, it was in the interest of bankers and -long-distance traders to batter the entrenched communal oligarchy with an eye to loosening the political monopoly of the old consular families, mostly of noble lineage… But after about 1250 or 1260, having fully achieved their aims and in fact now menaced by the political ambitions of the middle classes, they broke with the popolo, thereby dividing and undermining the popular movement”.[5]

With the erosion of nobility and its traditional privileges across Europe and North America from the 17th century onward, as well as the formal abolition of chattel slavery in these societies, this traditional understanding of middle classes is not sufficient for the world we inhabit. Being neither a slave nor a noble will not help many locate their social position in contemporary societies, when these societies do not formally legally recognize slavery or nobility. As capitalism remade societies across western Europe and North America in this same period, it reshaped the nature of the classes that composed those societies. Thus, a new way to understand what the middle-class is will be needed.

The Idea of the Middle Class in Post-WWII America

There are some who are reluctant to define the middle class using income measurements. The alternative proposed by many of these critics is a more aspirational definition based on consumption. This definition is based on both the level and the kind of consumption desired by individuals who aspire to be middle-class, ie. who desire to live what is deemed a middle-class lifestyle. Most of the essential features of this conception of the middle class are derived from the experience of Americans post WWII. The vast pool of purchasing power accumulated by US citizens during the war led in the post-war period to rising standards of living for a wide swath of the population. The patterns of consumption, the norms and values, of what we today consider definitional of the middle class in America were originated to a large extent in this period.

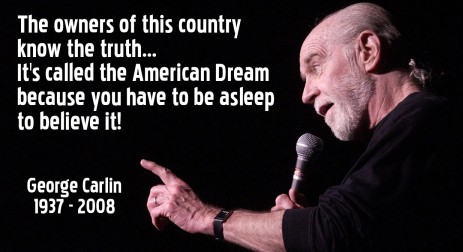

It was in this period that the idea of the “American Dream”, as it is currently understood, originates. This post-war vision of increasingly wealthy Americans achieving higher material standards of living is the well-spring of many of the elements of middle-class-ness that we take for granted. The conception of middle-class-ness as consisting of things like widespread home ownership, ownership of a motor vehicle or vehicles, stable long-term employment, ability to send children to college, take a family vacation, et cetera, was born during this era.

If we try to understand the middle class this way, we should investigate what the patterns of consumption for a middle-class individual, or family, today requires in terms of income, and how many Americans actually possess the financial means to afford this lifestyle. According to one recent report, it was estimated that a middle-class “American dream” lifestyle would cost $130,000 a year for a family of four.[6] The median income for individual income-earners in the US in 2013 was around $52,000, not even half of that estimated cost. According to a 2010 study by the Commerce Department only a family with two income-earners in the 75th percentile or above could afford the middle-class lifestyle described in the previous report. [7] According to data from a 2014 report by the Congressional Research Service only around 20% of American household could afford this price tag of a “middle-class” lifestyle.

If one takes only the items listed as “essential” in the report cited in the previous paragraph the total cost of a middle-class lifestyle, which is still above the current median income. This accounting clearly leaves out other important expenses, like taxes, that one will incur, as well as makes impossible any expenditure on important items like savings, and recreation. Now, of course food prices change, and fuel prices change, and these effect how wealthy consumers feel, as decreases in food and fuel costs can be transferred to increase consumption of “extras” like college savings for children, or family vacations. One should also note that this report categorized cell phone and internet expenditure as an “extra”. In today’s world these things are properly considered more akin to utilities, they are essentials for living.

Clearly, the level of income needed for achievement of a characteristically middle-class, or “American dream”, lifestyle is out of reach for a great many individuals and families. This is likely part of why the percentage of those identifying themselves as lower-class, or lower-middle class in recent surveys has increased.[8] Indeed, even a family with two income-earners, in the 25th percentile only has an income about equivalent to the median. Meanwhile, as of 2010, an individual income-earner in the 50th percentile only made around $25,000. The rising costs of college, the continued stagnation of wages – especially at the lowest ends of the labour market – as well as the reductions in employer-based pension and benefit programs for most workers have a contributed to making the mid-twentieth century American vision of middle-class existence more and more out of reach for large swaths of Americans.

The post-war American experience, if put in proper context, is the product of a historically unprecedented epoch. According to the research presented by Thomas Piketty in his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the middle part of the twentieth century was the only time in the last 300 years that his law of capital (r>g) was reversed.[9] This was a special period in which the growth rate exceeded the return to capital, and thus workers received increasing wages, and increasing purchasing power. It was in this historically unique period that the main expectations, norms, values, and status symbols of modern American “middle-class” lifestyle were born.

If we look the heyday of the American middle class in the 1950s and 1960s what we see is a transformation of American society born of a historical accident. Piketty’s research demonstrates that income inequality in the US basically plateaued over these decades, after decreasing sharply during the period from 1913-1945, that is the period of the World Wars and the Great Depression. What the French call “les trente glorieuses”, and others have called a pax Americana, was the direct result of the tumult of the wars and economic crises of the first half of the twentieth century. Workers in the western world generally experienced a boom, in that they experienced rising living standards, wages, and benefits. In Europe these benefits often took the form of national programs, while in America they were largely employer-based; healthcare and retirement are good examples. It was in this environment of rising levels of access to material consumption that the dominant aspects of the outlook of the middle class in America took shape.

Without the devastating effects of two world wars and an economic depression of immense scale, governments, especially in the US, would not have made the concessions that they did to workers, to organized labour in particular. The need to secure consistent, reliable production of vital war supplies, which might be disrupted by labour agitation, inclined the US government to enter the fray of industrial warfare on the side of workers during the First World War; at least to the extent required to ensure production for war. The Great Depression was an important cause of the establishment of the main pillars of the American welfare system in the 1930s. Labour unions achieved even greater privileges during the Second World War, as the leadership of organized labour organizations were increasingly co-opted by the corporate interests they were supposed to oppose. As a result of the need to take sometimes drastic measures to fight two wars and a titanic economic depression the US government enacted policies which resulted in a reduction in income inequality. This reduction in inequality combined with rising levels of material consumption, due to workers increased ability to bargain collectively with the support of the legal apparatus of the state, define this unprecedented period in economic history.

Middle Class Confusion

Clarification about the meaning of “middle class” is especially important because Americans seem to be confused about this notion of “middle class”, about who is in it, and what it means to be in it. It is a well-know and, much commented on, phenomenon in American political culture that almost everyone tends to perceive themselves as “middle-class”. What makes this fact interesting, and thus worthy of the decades of commentary and analysis it has received, is the startling economic inequality that coexists with this perception.

Though the rates of self-identification with being middle-class have varied over time, a healthy portion of Americans still identify as being middle class. Even now, after decades of erosion in the position of workers due to stagnating wages, reductions in benefits, cuts to social programs and education, increasing international competition, and the shifting of various kinds of work to the global south and other peripheral economies, as well as more recently the effects of the 2008 financial crisis, 44% of people surveyed in one recent survey self-identified as being middle-class. [10] Indeed this figure has fallen over the years of the Great Recession, self-identification as middle-class fell from 53% in 2008, to 49% in 2012, and then to 44% in 2014. Thus, even in bad times, as a great many people are still struggling, a great many people continue to perceive themselves as middle-class.

There is no one universally accepted way to define the middle-class. Perhaps this is part of the reason why politicians are able to make so much political hay with it. This is also part of how it is possible for a great many rather wealthy see themselves as middle-class at the same time as many of the working poor. It is also part of how many super-wealthy individuals come to perceive others less wealthy than themselves, though still obscenely wealthy, as ‘merely’ middle-class.[11] This lack of a consensus about a definition is certainly one of the reasons there is so much confusion about the middle-class, and who belongs to it, and how one belongs to it.

Conventionally, the middle is understood as everyone in the second, third, and fourth income quintiles. Basically, everyone who is not in the top-fifth or the bottom-fifth of income earners is defined as middle-class. In America today this definition of middle-class is roughly equivalent to those earning between $30,000 and $80,000 a year.[12] This is quite a large middle-class. One might think that it is rather too large. Indeed, how can one assimilate the experiences of an individual, or even more a family, living on $30,000 to one making $80,000? One could, I think quite properly, say that these two sets of experiences are so incommensurable materially as to make them awkward members of a common middle-class. Let us note in this connection that the federal government defines the poverty threshold for a family of four as a bit less than $24,000 a year. So, it would seem hard to think the experiences of family living on about 25% more than the poverty level would be anything like those of a family making more than two and a half times that amount.

That this conception is too wide to be very useful, and for the reasons I alluded to, is admitted by the fact that, at least colloquially, we have adopted the distinctions between ‘upper’ and ‘lower’ middle class. This distinction testifies to the difference in material position of individuals, or families, in the upper and lower ends of the middle. The lifestyle, the patterns of consumption, level of access to opportunity, and much else, varies so much between these groups that the distinction suggests itself, and is so patently apparent that no one questions its propriety.

Perhaps then we should narrow our definition of middle-class to only the third income quintile. This understanding of middle-class would include those making roughly $40,000 to $65,000. Even the top end of this range would still be half of what one estimate suggests a middle-class lifestyle would cost. Moreover, only about 15% of income earners would count as middle-class on this way of understanding the middle class. [13] This fact would certainly seem inconsistent with the widespread perception that the middle-class is the numerically largest class. Even if we expand back to our original range of $30-80,000, only about 40% of income earners would be middle-class. While this figure has the virtue of appearing to match up quite closely with the level of self-reported identification as being middle-class, it suffers from the vagueness we noted above. The upper limit of the 4th income quintile is north of $100,000. I do not think it is a stretch to say the material circumstances of a “middle-class” family making anywhere from the median to the upper limit has much in common with those families earning closer to the lower threshold of “middle class”.

By several ways of trying to understand the middle class we come up with results that fall short of matching our expectations and common perceptions. We seem to end up with either an unhelpfully expansive notion of the middle-class that encompasses individuals and families with greatly divergent material circumstances. Or, one ends up with a more precise statistical conception of the middle class, but wherein fewer persons are understood to be middle-class than commonly report being so in surveys. Part of explaining this confusion about the middle-class is the fact that Americans are either unaware or deeply confused about the nature of the distribution of wealth in this country. Many people report feeling like they are middle-class, but only as a result of ignorance or confusion about the nature of wealth inequality in America. Indeed, it would be crazy to deny that part of one’s perception of class position is the relative position of others. Were more Americans aware of the real nature of the distribution of wealth they would likely feel less middle-class, and more lower-class. According to the results of one recent research study, a representative sample of Americans reported thinking that the share of total income possessed by the middle class in America, i.e. the second through fourth income quintiles, was just north of 40%. Respondents also reported thinking the third income quintile alone possesses over 10% of total national wealth. In fact, the real share possessed by the first through fourth income quintiles combined is less than 20%, and the third quintile alone possesses closer to 5% than greater than the 10% that was reported.[14]

Another important aspect of the explanation for why there is so much confusion about the middle class is the confusion individuals face given their precarious position in the socio-economic hierarchy. Given how much inequality has risen over the last few decades there has been an increase in the perception that the post-war American middle-class lifestyle is out of reach for a great many hard-working people. Rising inequality combined with the effects of a calamitous financial crises, followed by years of recession, caused many to report falling in social class. The youngest cohort especially was hard hit, with now 49% reporting being in the lower or lower-middle class. It also caused many who identify as middle-class to feel this status increasingly precarious. Indeed, according to a Pew Research study from 2014 almost as many Americans reported being lower-class as middle-class, and the spread between the two was a mere 4%.[15]

The Working Class

We have seen now that this notion of the “middle class” is highly problematic. When we attempt a rational accounting of it, what we find is that our social reality confounds many of the expectations that most Americans have when they talk about the middle class. We find that though many Americans report in surveys that they are middle-class, the middle class is small, and shrinking. Once we distinguish upper from lower in the middle class, the true middle is really a small part of the income spectrum. One cannot get too far below the median income for one to be more lower class than middle class, nor can one get too far above without becoming upper-middle, or even elite. For instance, $100,000 in income would put one at the upper limit of the fourth income quintile, while an income at or above $150,000 would place one among the top 10% of income-earners. One cannot thus get too far beyond the $80,000 average income of the fourth income quintile without ending up less middle class than upper class.

If we judge belonging to the middle class as a function of ability to consume, then again we find that the traditional middle-class lifestyle ideal is increasingly out of reach for large swaths of the American population. What we see now is that we need a new way to think about class, about the socio-economic positions that people occupy and how these are best described. Getting a handle on what class one belongs to is important, especially in these election cycles, as appeals for votes are made to members of the various social classes that compose the electorate. How is one to know which kind of candidate or policy to vote for if one does not know what candidates or policies will advance their interests? And how is one to know what will advance one’s interests if one does know have an accurate understanding of their own socio-economic reality?

Rather than muddle on with this vague notion of a middle class, we should substitute a new understanding of class and class relations. This understanding of class should emphasize the role that working conditions play in determining socio-economic position, or class. This understanding will of course have much overlap with the dominant income-based understanding. For indeed, working conditions and wage rates are often highly correlated in market economies, that is, typically the lower the pay the worse the working conditions (in one form or another) and vice versa. When we take the kinds of jobs people work into account, the picture that emerges is one which demonstrates the importance of thinking in terms of a working class rather than a middle class. When we start putting working conditions in the forefront of our conception of social class we gain a much accurate, and explanatory conception of class.

One example that helps demonstrate this need for an understanding of class based on working conditions is the practice of “flex-time”. In the upper end of the labour market this concept is instantiated by programs that allow workers to do their work on their own schedule, freeing workers of the need to always be in the office during the traditional working day. This allows workers to achieve a better work-life balance, by having more flexibility with the time they need to devote to work. On the lower end of the labour market flex-time typically takes the form of on-call forms of scheduling. This is an extension of the logic of the “just-in-time” inventory management systems that have come to dominate manufacturing industries, and applied to the labour force of a variety of businesses, but especially retail firms. The idea, in both cases, is to only have as much as it needed of both on hand at any one time, so as to free up capital from unnecessary investment in extra stock or extra labour.

Conclusion

Have middle classes existed in history, yes. Did a middle class exist in the US during the middle part of the twentieth century, yes. However, in both cases these answers must be qualified, if the nuance of reality is not to be lost. Yet, in appending these qualifications we change the nature of the answers, and thus must come to see the original answer as importantly flawed. In both cases we find the reality of the middle class(es) does not match up with our modern expectations and perceptions about the middle class. In the first case, one might be subject to various forms of un-free labour despite still being technically not a slave, and thus free but by no means rich, or even independent. In the latter case, we find that this ideal of the middle class was quite restricted, and the alleged golden age of its reign was certainly not seen as such by the many marginalized groups of that era. We also see that its very existence occurs because of the confluence of historical circumstances that would be near impossible to re-create.

The idea of being “middle class” is also a source of confusion when compared to modern thinking about the middle class, and its role in society. Indeed, much of the meaning of being “middle class” has always involved poor people, those who work for wages for a living, aping the consumption trends of their ‘social betters’. Thus, even while during the classic 19th century hay-day of industrialization the middle class, ie. the petit bourgeoisie, was fairly small it nonetheless transmitted its social norms, consumption patterns, taste in art and décor, to those below them on the social ladder. It was not this middling class, but rather the working class, the proletariat, whose consumption, aping the middle class above them, drove the rise of a “middle class society”. This process of transmittal of social norms, values, and patterns of consumption is eloquently detailed by Thorsten Veblen in his Theory of the Leisure Class.

Today, this notion of the middle class, a remnant of the mid-century post-war Pax Americana, stands in the way of proper thinking about the role of class in society and the role of class in individuals’ lives. We need to be free of this notion if we’re going to able to correctly perceive how class works, and how it has changed. Remember that this notion of the middle class in post-war America was built on stable, long-term employment, with benefits, and pension plans, that paid enough to own a home, buy a car, household appliances, vacations, college educations, and more. In today’s economy these kinds of employment features of increasingly harder to come by for increasingly large segments of the labour market.

What one finds is that as automation increases, and as services increasingly dominate over production, more and more workers are forced into ever more precarious forms of employment. These tenuous relationships serve employers desire for flexibility, ie. ability to (re)move capital quickly, but increase burdens on working class people; especially on their time. Instead of thinking of themselves as “middle class”, these workers should more correctly perceive themselves to be part of what Guy Standing calls the Precariat[16]. The Precariat is already a class in-itself, but the ideology of the middle class in the US prevents it to a great extent from developing into a class for-itself. Opposed to this class is what Standing calls the Salariat, that is, the minority of a firms’ workers who are central to operations. These are core workers who typically earn a salary, have benefits, sick time, vacation days, and many of the other trappings of the fabled American middle class lifestyle.

Politicians will continue to talk in speeches, interviews, and the like about a middle class that supposedly exists in America, and how they will do the most to help it, typically by enacting the policies that will allow it to flourish. From what we have seen here working class people should no longer be duped into thinking that those politicians are addressing them. The rhetoric that dominates our politics simply does not match the reality of the contemporary economy, in particular the labour market. When we adopt a more appropriate view of class we see an economy characterized not by a broad-based and prosperous middle class, but rather by increasing inequality. We see a labour market where trends in job conditions and benefits very much resemble those in real wages. When we adopt a different view of class we see a very different answer to the question, Is there a middle class in America? No, not in a way that matches the mid-century American ideal.

Notes

[1] For a thorough analysis of the political and social conflict in the ancient Greek world see, G.E.M. de Ste. Croix’s The Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World. 1981. Cornell University Press, 1998.

[2] De Ste. Croix 1998, 284

[3] Martines, Lauro. Power and Imagination; City-States in Renaissance Italy. 1979. Vintage Books, 1980; 40.

[9] In Piketty’s equation (r) = after tax rate of return to capital, and (g) = the rate of growth of per capita income, a proxy for economic growth. For further information about Piketty’s research see my review of his book for The Hampton Institute.

[16] See his book, The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. Bloomsbury Academic; 2011.