By Michael Grasso

Source: We Are the Mutants

Splatter Capital: The Political Economy of Gore Films

By Mark Steven

Repeater Books, 2017

“Splatter confirms and redoubles our very worst fears. It reminds us of what capital is doing to all of us, all of the time—of how predators are consuming our life-substances; of how we are gravely vulnerable against the machinery of production and the matrices of exchange; and of how, as participants of an internecine conflict, our lives are always already precarious.”

—from the Introduction to Splatter Capital

Political readings or interpretations of horror films are nothing new. But in Mark Steven’s 2017 study, Splatter Capital, an explicit connection is made between the bloody gore of what Steven terms “splatter” horror films and the dehumanizing, mutilative forces of global capitalism. Moreover, Steven posits the artistic motivation behind splatter horror as an explicit repudiation of this system: “It is politically committed and its commitment tends toward the anti-capitalist left.” In splatter films, Steven tells us, the images of gory dismemberment do double duty. They both offer a clear metaphor for capitalism’s cruelty, and act as a cathartic revenge in which the bloody legacy of capitalist exploitation is often visited upon its perpetrators and profiteers among the bourgeoisie.

Some definitions are in order here, given that Steven’s schema of genres—“splatter,” “slasher,” “extreme horror”—draws distinctions that might not be apparent even to horror fans. Splatter horror, according to Steven, is all about the violence that can be visited upon the human body and all the abjection that follows. It is machinery tearing apart flesh, blood, and guts: the moment a human body becomes meat. It differs from the personalized and often sexualized “hunt” of the slasher flick. The protagonist in a slasher movie is an individual (often female) resisting violent death at the hands of another individual (often male). In victory against Jason, Freddy, or Michael Myers, this protagonist, in Steven’s words, “restores a social order, which is all too regularly white, middle-class, and suburban.” Splatter horror not only expands the horizons of mutilation and violence allowable in a horror film but systematizes it. The splatter enemy is an implacable, impersonal force, full of shock and awe; its grudge is not personal, but instead overwhelming, inescapable, and, most importantly, class-based.

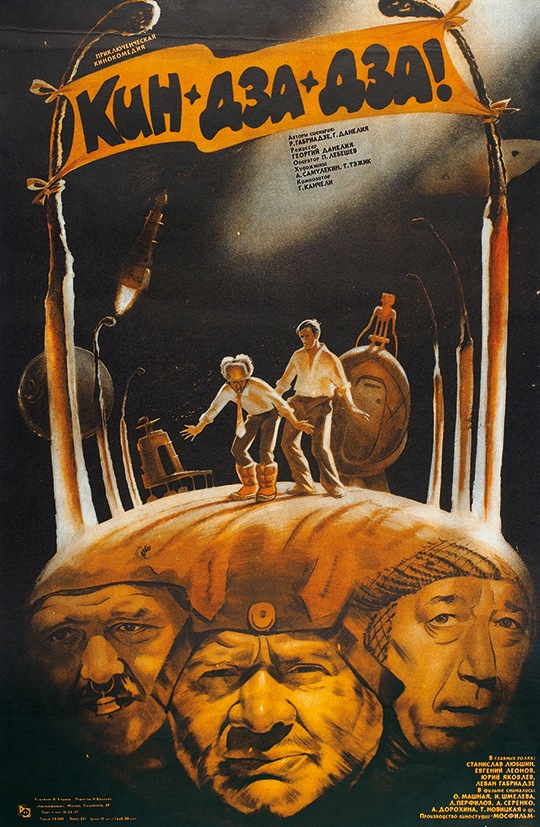

The language of violence and horror has been with Marxist thought from the beginning. Steven gives us a good précis of Marx’s use of explicitly Gothic (along with bloody and cannibalistic) imagery throughout his works, as well as a splatter-tastic explanation of the exploitation behind surplus value, using an imaginary case study in the manufacturing of chainsaws and knives. The October Revolution in Russia is viewed as a reaction to the inhuman mechanized slaughter of the first World War; Eisenstein’s early filmic paeans to the necessity of revolution such as Strike (1925) demonstrate, thanks to Eisenstein’s pioneering use of montage, capitalism’s role as butcher. Steven also discusses avowed leftist filmmakers from outside the Soviet Union such as Godard, Makavejev, and Pasolini—specifically their use of gore to embody the cruelty of the ruling classes.

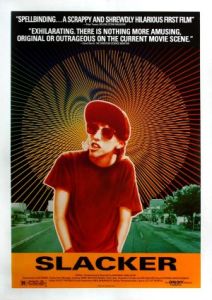

As we enter the world of Hollywood film in Chapter Three, Steven examines splatter film as a specifically American reaction to the constant churning crisis of capitalism. Specifically, Steven looks at the two peaks of gore-flecked horror—the mid ’60s through the early ’80s, and the post-Cold War “torture porn” trend of the early ’00s—as expressions of two very important economic and political shifts. The first splatter peak in the ’70s is seen as a clear reaction to the slow, inexorable widening of neoliberal and globalist postindustrial economics and its impact on the American industrial worker. (The aftermath of this trend continues into the 1980s with the evaporation of industry and the establishment of a new information-and-finance-based economy.) The splatter/torture porn trend of the ’00s and beyond is a reaction to the crises of capitalism under a new world order of neocolonialist conflict: the War on Terror, the final disestablishment of the Western industrial base in favor of cheap labor in the developing world, and the new interconnected, networked world’s rulership by speculative capital in the form of the finance sector.

Steven cites too many splatter movies to cover in this review, but central to his thesis is the seminal 1974 Tobe Hooper film, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. The death of local industry leads Leatherface and family to keep their slaughterhouse traditions alive by carving up and eating young people. These young people, Steven is quick to point out, are only here at all because they were unable to get gas for their car (thanks to the first of two 1970s oil crises). American decline is everywhere; betrayal by global economic forces are central to the trap that’s being laid by the cannibals. (Of course, the carnage of the Vietnam War can’t be overlooked here either, given the visual language of ambush, capture, and torture; Hooper himself has cited this in subsequent interviews.) Steven notes that the victims in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre are representative of a bourgeoisie who don’t know how the sausage is made. It’s important and vital, Steven says, that the cannibalistic side of splatter involves the bourgeoisie being forced to eat members of their own class. It’s Burroughs’s famous “naked lunch“: “the frozen moment when everyone sees what is at the end of every fork.”

As the neoliberal takeover of the world economy begins in earnest in the 1980s, as complex and largely ephemeral systems of mass media and finance take the place of the visceral, grinding monomania of industrial capitalism, splatter horror follows suit. Steven’s analysis of David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983) is especially sharp, examining the links between the body horror of the film and the Deleuzian body without organs. Max Renn’s body becomes an endlessly modular media node, able to accommodate video cassettes, to generate and fuse with phallic weapons (used to assassinate and destroy the media forces who’ve made him this way), to mesh and mold and mix with the hard plastic edges of media technology. By the end of the film, Renn is a weapon reprogrammed and re-trained on the very media-industrial complex that made him. More body horror: the cult classic Society (1989) and its shocking conclusion posits the ruling class as a cancerous monster, an amorphous leviathan straight out of a Gilded Age political cartoon, eating and fucking and vomiting, red in tooth and claw and pseudopod. Barriers between bodies break down; the system begins swallowing up all alternate possibilities.

By the time the Cold War is finished, the era of post-9/11 eternal war, of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo, led to the popular new splatter sub-genre of “torture porn.” Steven identifies the genre’s distinguishing aesthetic feature: the indisputable, systematic, and worldwide victory of capitalism and the hypnotic Spectacle that accompanies it. In this era, there are no longer any alternatives. Everyone, rich and poor, is trapped in the system, and the system reintegrates torture into a worldwide video spectacle. This is embodied in both the global conspiracies of the wealthy in Roth’s Hostel series and in the Jigsaw Killer’s industrially-themed Rube Goldberg devices in the Saw franchise—devices of dismemberment explicitly linked to moral quandaries reminiscent of capitalism’s impossible everyday Hobson’s choices for the working class. The system will go on consuming you, whether you’re unlucky enough to be a splatter film’s victim, or “lucky” enough to wield the power to splatter (for example, Hostel: Part II‘s reversal of fate on the ultra-wealthy hunters, or the Jigsaw Killer’s death from cancer in Saw III—ultimately due to… a lack of health insurance).

Possibly the most intriguing aspect of this already very good book is Steven’s interspersing of personal anecdotes on when and where he discovered some of his favorite horror and genre films. By placing his personal and psychological experience of splatter films front and center, and linking it to his personal growth and increasing political maturity, he demonstrates the personal impact of the political, and the necessity of personal epiphany, mediated by culture, to achieve political awareness. Splatter Capital ultimately is not a book for the already-convinced and committed leftist, the Marxian thinker already well-versed in theory. (Another of Splatter Capital‘s very strong points is how Steven largely eschews jargon and obscurantism for an approachable tone and topic that laypeople can dive into easily.) It is for the fans of these films who’ve always wondered about the ineluctable appeal of visceral, shocking violence on screen, and perhaps why it all feels so strangely familiar.