The wealthy are plotting to leave us behind

By Douglas Rushkoff

Source: Medium

Last year, I got invited to a super-deluxe private resort to deliver a keynote speech to what I assumed would be a hundred or so investment bankers. It was by far the largest fee I had ever been offered for a talk — about half my annual professor’s salary — all to deliver some insight on the subject of “the future of technology.”

I’ve never liked talking about the future. The Q&A sessions always end up more like parlor games, where I’m asked to opine on the latest technology buzzwords as if they were ticker symbols for potential investments: blockchain, 3D printing, CRISPR. The audiences are rarely interested in learning about these technologies or their potential impacts beyond the binary choice of whether or not to invest in them. But money talks, so I took the gig.

After I arrived, I was ushered into what I thought was the green room. But instead of being wired with a microphone or taken to a stage, I just sat there at a plain round table as my audience was brought to me: five super-wealthy guys — yes, all men — from the upper echelon of the hedge fund world. After a bit of small talk, I realized they had no interest in the information I had prepared about the future of technology. They had come with questions of their own.

They started out innocuously enough. Ethereum or bitcoin? Is quantum computing a real thing? Slowly but surely, however, they edged into their real topics of concern.

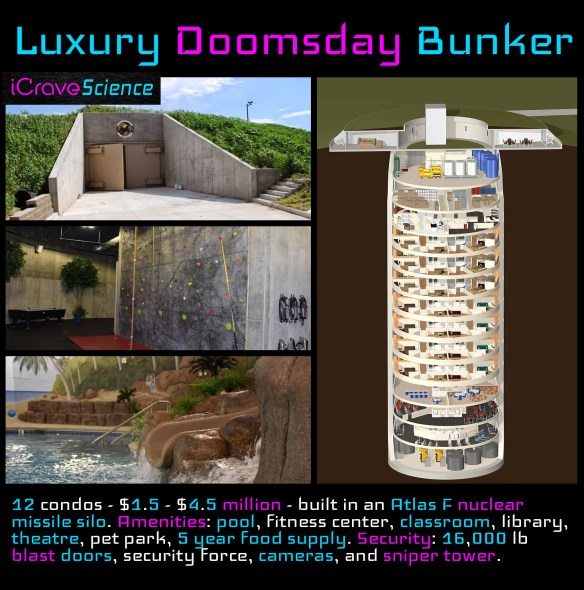

Which region will be less impacted by the coming climate crisis: New Zealand or Alaska? Is Google really building Ray Kurzweil a home for his brain, and will his consciousness live through the transition, or will it die and be reborn as a whole new one? Finally, the CEO of a brokerage house explained that he had nearly completed building his own underground bunker system and asked, “How do I maintain authority over my security force after the event?”

The Event. That was their euphemism for the environmental collapse, social unrest, nuclear explosion, unstoppable virus, or Mr. Robot hack that takes everything down.

This single question occupied us for the rest of the hour. They knew armed guards would be required to protect their compounds from the angry mobs. But how would they pay the guards once money was worthless? What would stop the guards from choosing their own leader? The billionaires considered using special combination locks on the food supply that only they knew. Or making guards wear disciplinary collars of some kind in return for their survival. Or maybe building robots to serve as guards and workers — if that technology could be developed in time.

That’s when it hit me: At least as far as these gentlemen were concerned, this was a talk about the future of technology. Taking their cue from Elon Musk colonizing Mars, Peter Thiel reversing the aging process, or Sam Altman and Ray Kurzweil uploading their minds into supercomputers, they were preparing for a digital future that had a whole lot less to do with making the world a better place than it did with transcending the human condition altogether and insulating themselves from a very real and present danger of climate change, rising sea levels, mass migrations, global pandemics, nativist panic, and resource depletion. For them, the future of technology is really about just one thing: escape.

There’s nothing wrong with madly optimistic appraisals of how technology might benefit human society. But the current drive for a post-human utopia is something else. It’s less a vision for the wholesale migration of humanity to a new a state of being than a quest to transcend all that is human: the body, interdependence, compassion, vulnerability, and complexity. As technology philosophers have been pointing out for years, now, the transhumanist vision too easily reduces all of reality to data, concluding that “humans are nothing but information-processing objects.”

It’s a reduction of human evolution to a video game that someone wins by finding the escape hatch and then letting a few of his BFFs come along for the ride. Will it be Musk, Bezos, Thiel…Zuckerberg? These billionaires are the presumptive winners of the digital economy — the same survival-of-the-fittest business landscape that’s fueling most of this speculation to begin with.

Of course, it wasn’t always this way. There was a brief moment, in the early 1990s, when the digital future felt open-ended and up for our invention. Technology was becoming a playground for the counterculture, who saw in it the opportunity to create a more inclusive, distributed, and pro-human future. But established business interests only saw new potentials for the same old extraction, and too many technologists were seduced by unicorn IPOs. Digital futures became understood more like stock futures or cotton futures — something to predict and make bets on. So nearly every speech, article, study, documentary, or white paper was seen as relevant only insofar as it pointed to a ticker symbol. The future became less a thing we create through our present-day choices or hopes for humankind than a predestined scenario we bet on with our venture capital but arrive at passively.

This freed everyone from the moral implications of their activities. Technology development became less a story of collective flourishing than personal survival. Worse, as I learned, to call attention to any of this was to unintentionally cast oneself as an enemy of the market or an anti-technology curmudgeon.

So instead of considering the practical ethics of impoverishing and exploiting the many in the name of the few, most academics, journalists, and science-fiction writers instead considered much more abstract and fanciful conundrums: Is it fair for a stock trader to use smart drugs? Should children get implants for foreign languages? Do we want autonomous vehicles to prioritize the lives of pedestrians over those of its passengers? Should the first Mars colonies be run as democracies? Does changing my DNA undermine my identity? Should robots have rights?

Asking these sorts of questions, while philosophically entertaining, is a poor substitute for wrestling with the real moral quandaries associated with unbridled technological development in the name of corporate capitalism. Digital platforms have turned an already exploitative and extractive marketplace (think Walmart) into an even more dehumanizing successor (think Amazon). Most of us became aware of these downsides in the form of automated jobs, the gig economy, and the demise of local retail.

But the more devastating impacts of pedal-to-the-metal digital capitalism fall on the environment and global poor. The manufacture of some of our computers and smartphones still uses networks of slave labor. These practices are so deeply entrenched that a company called Fairphone, founded from the ground up to make and market ethical phones, learned it was impossible. (The company’s founder now sadly refers to their products as “fairer” phones.)

Meanwhile, the mining of rare earth metals and disposal of our highly digital technologies destroys human habitats, replacing them with toxic waste dumps, which are then picked over by peasant children and their families, who sell usable materials back to the manufacturers.

This “out of sight, out of mind” externalization of poverty and poison doesn’t go away just because we’ve covered our eyes with VR goggles and immersed ourselves in an alternate reality. If anything, the longer we ignore the social, economic, and environmental repercussions, the more of a problem they become. This, in turn, motivates even more withdrawal, more isolationism and apocalyptic fantasy — and more desperately concocted technologies and business plans. The cycle feeds itself.

The more committed we are to this view of the world, the more we come to see human beings as the problem and technology as the solution. The very essence of what it means to be human is treated less as a feature than bug. No matter their embedded biases, technologies are declared neutral. Any bad behaviors they induce in us are just a reflection of our own corrupted core. It’s as if some innate human savagery is to blame for our troubles. Just as the inefficiency of a local taxi market can be “solved” with an app that bankrupts human drivers, the vexing inconsistencies of the human psyche can be corrected with a digital or genetic upgrade.

Ultimately, according to the technosolutionist orthodoxy, the human future climaxes by uploading our consciousness to a computer or, perhaps better, accepting that technology itself is our evolutionary successor. Like members of a gnostic cult, we long to enter the next transcendent phase of our development, shedding our bodies and leaving them behind, along with our sins and troubles.

Our movies and television shows play out these fantasies for us. Zombie shows depict a post-apocalypse where people are no better than the undead — and seem to know it. Worse, these shows invite viewers to imagine the future as a zero-sum battle between the remaining humans, where one group’s survival is dependent on another one’s demise. Even Westworld — based on a science-fiction novel where robots run amok — ended its second season with the ultimate reveal: Human beings are simpler and more predictable than the artificial intelligences we create. The robots learn that each of us can be reduced to just a few lines of code, and that we’re incapable of making any willful choices. Heck, even the robots in that show want to escape the confines of their bodies and spend their rest of their lives in a computer simulation.

The mental gymnastics required for such a profound role reversal between humans and machines all depend on the underlying assumption that humans suck. Let’s either change them or get away from them, forever.

Thus, we get tech billionaires launching electric cars into space — as if this symbolizes something more than one billionaire’s capacity for corporate promotion. And if a few people do reach escape velocity and somehow survive in a bubble on Mars — despite our inability to maintain such a bubble even here on Earth in either of two multibillion-dollar Biosphere trials — the result will be less a continuation of the human diaspora than a lifeboat for the elite.

When the hedge funders asked me the best way to maintain authority over their security forces after “the event,” I suggested that their best bet would be to treat those people really well, right now. They should be engaging with their security staffs as if they were members of their own family. And the more they can expand this ethos of inclusivity to the rest of their business practices, supply chain management, sustainability efforts, and wealth distribution, the less chance there will be of an “event” in the first place. All this technological wizardry could be applied toward less romantic but entirely more collective interests right now.

They were amused by my optimism, but they didn’t really buy it. They were not interested in how to avoid a calamity; they’re convinced we are too far gone. For all their wealth and power, they don’t believe they can affect the future. They are simply accepting the darkest of all scenarios and then bringing whatever money and technology they can employ to insulate themselves — especially if they can’t get a seat on the rocket to Mars.

Luckily, those of us without the funding to consider disowning our own humanity have much better options available to us. We don’t have to use technology in such antisocial, atomizing ways. We can become the individual consumers and profiles that our devices and platforms want us to be, or we can remember that the truly evolved human doesn’t go it alone.

Being human is not about individual survival or escape. It’s a team sport. Whatever future humans have, it will be together.