By John & Nisha Whitehead

Source: The Rutherford Institute

“If all that Americans want is security, they can go to prison. They’ll have enough to eat, a bed and a roof over their heads. But if an American wants to preserve his dignity and his equality as a human being, he must not bow his neck to any dictatorial government.”— President Dwight D. Eisenhower

The government wants us to bow down to its dictates.

It wants us to buy into the fantasy that we are living the dream, when in fact, we are trapped in an endless nightmare of servitude and oppression.

Indeed, with every passing day, life in the American Police State increasingly resembles life in the dystopian television series The Prisoner.

First broadcast 55 years ago in the U.S., The Prisoner—described as “James Bond meets George Orwell filtered through Franz Kafka”—confronted societal themes that are still relevant today: the rise of a police state, the loss of freedom, round-the-clock surveillance, the corruption of government, totalitarianism, weaponization, group think, mass marketing, and the tendency of human beings to meekly accept their lot in life as prisoners in a prison of their own making.

Perhaps the best visual debate ever on individuality and freedom, The Prisoner centers around a British secret agent who abruptly resigns only to find himself imprisoned in a virtual prison disguised as a seaside paradise with parks and green fields, recreational activities and even a butler.

While luxurious, the Village’s inhabitants have no true freedom, they cannot leave the Village, they are under constant surveillance, all of their movements tracked by militarized drones, and stripped of their individuality so that they are identified only by numbers.

“I am not a number. I am a free man,” is the mantra chanted in each episode of The Prisoner, which was largely written and directed by Patrick McGoohan, who also played the title role of Number Six, the imprisoned government agent.

Throughout the series, Number Six is subjected to interrogation tactics, torture, hallucinogenic drugs, identity theft, mind control, dream manipulation, and various forms of social indoctrination and physical coercion in order to “persuade” him to comply, give up, give in and subjugate himself to the will of the powers-that-be.

Number Six refuses to comply.

In every episode, Number Six resists the Village’s indoctrination methods, struggles to maintain his own identity, and attempts to escape his captors. “I will not make any deals with you,” he pointedly remarks to Number Two, the Village administrator a.k.a. prison warden. “I’ve resigned. I will not be pushed, filed, stamped, indexed, debriefed or numbered. My life is my own.”

Yet no matter how far Number Six manages to get in his efforts to escape, it’s never far enough.

Watched by surveillance cameras and other devices, Number Six’s attempts to escape are continuously thwarted by ominous white balloon-like spheres known as “rovers.”

Still, he refuses to give up.

“Unlike me,” he says to his fellow prisoners, “many of you have accepted the situation of your imprisonment, and will die here like rotten cabbages.”

Number Six’s escapes become a surreal exercise in futility, each episode an unfunny, unsettling Groundhog’s Day that builds to the same frustrating denouement: there is no escape.

As journalist Scott Thill concludes for Wired, “Rebellion always comes at a price. During the acclaimed run of The Prisoner, Number Six is tortured, battered and even body-snatched: In the episode ‘Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling,’ his mind is transplanted to another man’s body. Number Six repeatedly escapes The Village only to be returned to it in the end, trapped like an animal, overcome by a restless energy he cannot expend, and betrayed by nearly everyone around him.”

The series is a chilling lesson about how difficult it is to gain one’s freedom in a society in which prison walls are disguised within the seemingly benevolent trappings of technological and scientific progress, national security and the need to guard against terrorists, pandemics, civil unrest, etc.

As Thill noted, “The Prisoner was an allegory of the individual, aiming to find peace and freedom in a dystopia masquerading as a utopia.”

The Prisoner’s Village is also an apt allegory for the American Police State, which is rapidly transitioning into a full-fledged Surveillance State: it gives the illusion of freedom while functioning all the while like a prison: controlled, watchful, inflexible, punitive, deadly and inescapable.

The American Surveillance State, much like The Prisoner’s Village, is a metaphorical panopticon, a circular prison in which the inmates are monitored by a single watchman situated in a central tower. Because the inmates cannot see the watchman, they are unable to tell whether or not they are being watched at any given time and must proceed under the assumption that they are always being watched.

Eighteenth century social theorist Jeremy Bentham envisioned the panopticon prison to be a cheaper and more effective means of “obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example.”

Bentham’s panopticon, in which the prisoners are used as a source of cheap, menial labor, has become a model for the modern surveillance state in which the populace is constantly being watched, controlled and managed by the powers-that-be while funding its existence.

Nowhere to run and nowhere to hide: this is the mantra of the architects of the Surveillance State and their corporate collaborators.

Government eyes are watching you.

They see your every move: what you read, how much you spend, where you go, with whom you interact, when you wake up in the morning, what you’re watching on television and reading on the internet.

Every move you make is being monitored, mined for data, crunched, and tabulated in order to amass a profile of who you are, what makes you tick, and how best to control you when and if it becomes necessary to bring you in line.

When the government sees all and knows all and has an abundance of laws to render even the most seemingly upstanding citizen a criminal and lawbreaker, then the old adage that you’ve got nothing to worry about if you’ve got nothing to hide no longer applies.

Apart from the obvious dangers posed by a government that feels justified and empowered to spy on its people and use its ever-expanding arsenal of weapons and technology to monitor and control them, we’re approaching a time in which we will be forced to choose between bowing down in obedience to the dictates of the government—i.e., the law, or whatever a government official deems the law to be—and maintaining our individuality, integrity and independence.

When people talk about privacy, they mistakenly assume it protects only that which is hidden behind a wall or under one’s clothing. The courts have fostered this misunderstanding with their constantly shifting delineation of what constitutes an “expectation of privacy.” And technology has furthered muddied the waters.

However, privacy is so much more than what you do or say behind locked doors. It is a way of living one’s life firm in the belief that you are the master of your life, and barring any immediate danger to another person (which is far different from the carefully crafted threats to national security the government uses to justify its actions), it’s no one’s business what you read, what you say, where you go, whom you spend your time with, and how you spend your money.

Unfortunately, George Orwell’s 1984—where “you had to live—did live, from habit that became instinct—in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinized”—has now become our reality.

We now find ourselves in the unenviable position of being monitored, managed, corralled and controlled by technologies that answer to government and corporate rulers.

Consider that on any given day, the average American going about his daily business will be monitored, surveilled, spied on and tracked in more than 20 different ways, by both government and corporate eyes and ears.

A byproduct of this new age in which we live, whether you’re walking through a store, driving your car, checking email, or talking to friends and family on the phone, you can be sure that some government agency is listening in and tracking your behavior.

This doesn’t even begin to touch on the corporate trackers that monitor your purchases, web browsing, Facebook posts and other activities taking place in the cyber sphere.

Stingray devices mounted on police cars to warrantlessly track cell phones, Doppler radar devices that can detect human breathing and movement within in a home, license plate readers that can record up to 1800 license plates per minute, sidewalk and “public space” cameras coupled with facial recognition and behavior-sensing technology that lay the groundwork for police “pre-crime” programs, police body cameras that turn police officers into roving surveillance cameras, the internet of things: all of these technologies (and more) add up to a society in which there’s little room for indiscretions, imperfections, or acts of independence—especially not when the government can listen in on your phone calls, read your emails, monitor your driving habits, track your movements, scrutinize your purchases and peer through the walls of your home.

As French philosopher Michel Foucault concluded in his 1975 book Discipline and Punish, “Visibility is a trap.”

This is the electronic concentration camp—the panopticon prison—the Village—in which we are now caged.

It is a prison from which there will be no escape. Certainly not if the government and its corporate allies have anything to say about it.

As Glenn Greenwald notes:

“The way things are supposed to work is that we’re supposed to know virtually everything about what [government officials] do: that’s why they’re called public servants. They’re supposed to know virtually nothing about what we do: that’s why we’re called private individuals. This dynamic – the hallmark of a healthy and free society – has been radically reversed. Now, they know everything about what we do, and are constantly building systems to know more. Meanwhile, we know less and less about what they do, as they build walls of secrecy behind which they function. That’s the imbalance that needs to come to an end. No democracy can be healthy and functional if the most consequential acts of those who wield political power are completely unknown to those to whom they are supposed to be accountable.”

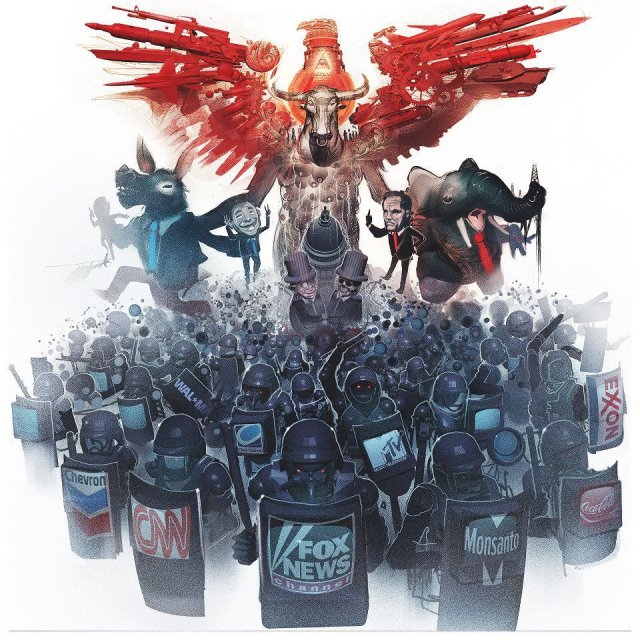

None of this will change, no matter which party controls Congress or the White House, because despite all of the work being done to help us buy into the fantasy that things will change if we just elect the right candidate, we’ll still be prisoners of the Village.

So how do you escape? For starters, resist the urge to conform to a group mind and the tyranny of mob-think as controlled by the Deep State.

Think for yourself. Be an individual.

As McGoohan commented in 1968, “At this moment individuals are being drained of their personalities and being brainwashed into slaves… As long as people feel something, that’s the great thing. It’s when they are walking around not thinking and not feeling, that’s tough. When you get a mob like that, you can turn them into the sort of gang that Hitler had.”

You want to be free? Remove the blindfold that blinds you to the Deep State’s con game, stop doping yourself with government propaganda, and break free of the political chokehold that has got you marching in lockstep with tyrants and dictators.

As I make clear in my book Battlefield America: The War on the American People and in its fictional counterpart The Erik Blair Diaries, until you come to terms with the fact that the government is the problem (no matter which party dominates), you’ll never stop being prisoners.