By Colin Todhunter

Source: Dissident Voice

The UK government’s Behavioural Insights Team helped to push the public towards accepting the COVID narrative, restrictions and lockdowns. It is now working on ‘nudging’ people towards further possible restrictions or at least big changes in their behaviour in the name of ‘climate emergency’. From frequent news stories and advertisements to soap opera storylines and government announcements, the message about impending climate catastrophe is almost relentless.

Part of the messaging includes blaming the public’s consumption habits for a perceived ‘climate emergency’. At the same time, young people are being told that we only have a decade or so (depending on who is saying it) to ‘save the planet’.

Setting the agenda are powerful corporations that helped degrade much of the environment in the first place. But ordinary people, not the multi-billionaires pushing this agenda, will pay the price for this as living more frugally seems to be part of the programme (‘own nothing and be happy’). Could we at some future point see ‘climate emergency’ lockdowns, not to ‘save the NHS’ but to ‘save the planet’?

A tendency to focus on individual behaviour and not ‘the system’ exists.

But let us not forget this is a system that deliberately sought to eradicate a culture of self-reliance that prevailed among the working class in the 19th century (self-education, recycling products, a culture of thrift, etc) via advertising and a formal school education that ensured conformity and set in motion a lifetime of wage labour and dependency on the products manufactured by an environmentally destructive capitalism.

A system that has its roots in inflicting massive violence across the globe to exert control over land and resources elsewhere.

In his 2018 book The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequalities and its solutions, Jason Hickel describes the processes involved in Europe’s wealth accumulation over a 150-year period of colonialism that resulted in tens of millions of deaths.

By using other countries’ land, Britain effectively doubled the size of arable land in its control. This made it more practical to then reassign the rural population at home (by stripping people of their means of production) to industrial labour. This too was underpinned by massive violence (burning villages, destroying houses, razing crops).

Hickel argues that none of this was inevitable but was rooted in the fear of being left behind by other countries because of Europe’s relative lack of land resources to produce commodities.

This is worth bearing in mind as we currently witness a fundamental shift in our relationship to the state resulting from authoritarian COVID-related policies and the rapidly emerging corporate-led green agenda. We should never underestimate the ruthlessness involved in the quest for preserving wealth and power and the propensity for wrecking lives and nature to achieve this.

Commodification of nature

Current green agenda ‘solutions’ are based on a notion of ‘stakeholder’ capitalism or private-public partnerships whereby vested interests are accorded greater weight, with governments and public money merely facilitating the priorities of private capital.

A key component of this strategy involves the ‘financialisation of nature’ and the production of new ‘green’ markets to deal with capitalism’s crisis of over accumulation and weak consumer demand caused by decades of neoliberal policies and the declining purchasing power of working people. The banking sector is especially set to make a killing via ‘green profiling’ and ‘green bonds’.

According to Friends of the Earth (FoE), corporations and states will use the financialisation of nature discourse to weaken laws and regulations designed to protect the environment with the aim of facilitating the goals of extractive industries, while allowing mega-infrastructure projects in protected areas and other contested places.

Global corporations will be able to ‘offset’ (greenwash) their activities by, for example, protecting or planting a forest elsewhere (on indigenous people’s land) or perhaps even investing in (imposing) industrial agriculture which grows herbicide-resistant GMO commodity crop monocultures that are misleadingly portrayed as ‘climate friendly’.

Offsetting schemes allow companies to exceed legally defined limits of destruction at a particular location, or destroy protected habitat, on the promise of compensation elsewhere; and allow banks to finance such destruction on the same premise.

This agenda could result in the weakening of current environmental protection legislation or its eradication in some regions under the pretext of compensating for the effects elsewhere. How ecoservice ‘assets’ (for example, a forest that performs a service to the ecosystem by acting as a carbon sink) are to be evaluated in a monetary sense is very likely to be done on terms that are highly favourable to the corporations involved, meaning that environmental protection will play second fiddle to corporate and finance sector return-on-investment interests.

As FoE argues, business wants this system to be implemented on its terms, which means the bottom line will be more important than stringent rules that prohibit environmental destruction.

Saving capitalism

The envisaged commodification of nature will ensure massive profit-seeking opportunities through the opening up of new markets and the creation of fresh investment instruments.

Capitalism needs to keep expanding into or creating new markets to ensure the accumulation of capital to offset the tendency for the general rate of profit to fall (according to writer Ted Reese, it has trended downwards from an estimated 43% in the 1870s to 17% in the 2000s). The system suffers from a rising overaccumulation (surplus) of capital.Reese notes that, although wages and corporate taxes have been slashed, the exploitability of labour continued to become increasingly insufficient to meet the demands of capital accumulation. By late 2019, the world economy was suffocating under a mountain of debt. Many companies could not generate enough profit and falling turnover, squeezed margins, limited cashflows and highly leveraged balance sheets were prevalent. In effect, economic growth was already grinding to a halt prior to the massive stock market crash in February 2020.

In the form of COVID ‘relief’, there has been a multi-trillion bailout for capitalism as well as the driving of smaller enterprises to bankruptcy. Or they have being swallowed up by global interests. Either way, the likes of Amazon and other predatory global corporations have been the winners.

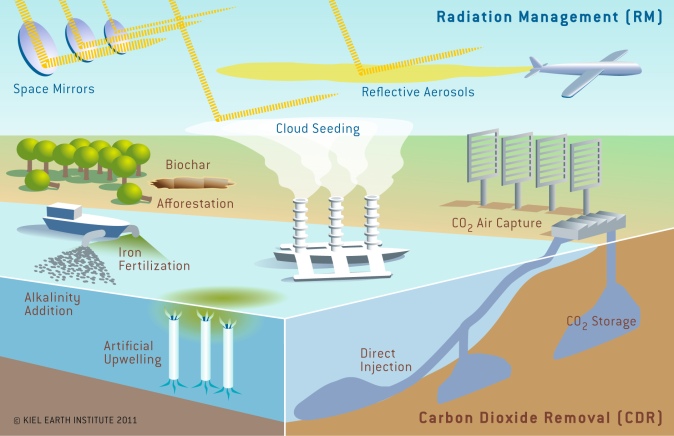

New ‘green’ Ponzi trading schemes to offset carbon emissions and commodify ‘ecoservices’ along with electric vehicles and an ‘energy transition’ represent a further restructuring of the capitalist economy, resulting in a shift away from a consumer oriented demand-led system.

It essentially leaves those responsible for environmental degradation at the wheel, imposing their will and their narrative on the rest of us.

Global agribusiness

Between 2000 and 2009, Indonesia supplied more than half of the global palm oil market at an annual expense of some 340,000 hectares of Indonesian countryside. Consider too that Brazil and Indonesia have spent over 100 times more in subsidies to industries that cause deforestation than they received in international conservation aid from the UN to prevent it.

These two countries gave over $40bn in subsidies to the palm oil, timber, soy, beef and biofuels sectors between 2009 and 2012, some 126 times more than the $346m they received to preserve their rain forests.

India is the world’s leading importer of palm oil, accounting for around 15% of the global supply. It imports over two-thirds of its palm oil from Indonesia.

Until the mid-1990s, India was virtually self-sufficient in edible oils. Under pressure from the World Trade Organization (WTO), import tariffs were reduced, leading to an influx of cheap (subsidised) edible oil imports that domestic farmers could not compete with. This was a deliberate policy that effectively devastated the home-grown edible oils sector and served the interests of palm oil growers and US grain and agriculture commodity company Cargill, which helped write international trade rules to secure access to the Indian market on its terms.

Indonesia leads the world in global palm oil production, but palm oil plantations have too often replaced tropical forests, leading to the killing of endangered species and the uprooting of local communities as well as contributing to the release of potential environment-damaging gases. Indonesia emits more of these gases than any country besides China and the US, largely due to the production of palm oil.

The issue of palm oil is one example from the many that could be provided to highlight how the drive to facilitate corporate need and profit trumps any notion of environmental protection or addressing any ‘climate emergency’. Whether it is in Indonesia, Latin America or elsewhere, transnational agribusiness – and the system of globalised industrial commodity crop agriculture it promotes – fuels much of the destruction we see today.

Even if the mass production of lab-created food, under the guise of ‘saving the planet’ and ‘sustainability’, becomes logistically possible (which despite all the hype is not at this stage), it may still need biomass and huge amounts of energy. Whose land will be used to grow these biomass commodities and which food crops will they replace? And will it involve that now-famous Gates’ euphemism ‘land mobility’ (farmers losing their land)?

Microsoft is already mapping Indian farmers’ lands and capturing agriculture datasets such as crop yields, weather data, farmers’ personal details, profile of land held (cadastral maps, farm size, land titles, local climatic and geographical conditions), production details (crops grown, production history, input history, quality of output, machinery in possession) and financial details (input costs, average return, credit history).

Is this an example of stakeholder-partnership capitalism, whereby a government facilitates the gathering of such information by a private player which can then use the data for developing a land market (courtesy of land law changes that the government enacts) for institutional investors at the expense of smallholder farmers who find themselves ‘land mobile’? This is a major concern among farmers and civil society in India.

Back in 2017, agribusiness giant Monsanto was judged to have engaged in practices that impinged on the basic human right to a healthy environment, the right to food and the right to health. Judges at the ‘Monsanto Tribunal’, held in The Hague, concluded that if ecocide were to be formally recognised as a crime in international criminal law, Monsanto could be found guilty.

The tribunal called for the need to assert the primacy of international human and environmental rights law. However, it was also careful to note that an existing set of legal rules serves to protect investors’ rights in the framework of the WTO and in bilateral investment treaties and in clauses in free trade agreements. These investor trade rights provisions undermine the capacity of nations to maintain policies, laws and practices protecting human rights and the environment and represent a disturbing shift in power.

The tribunal denounced the severe disparity between the rights of multinational corporations and their obligations.

While the Monsanto Tribunal judged that company to be guilty of human rights violations, including crimes against the environment, in a sense we also witnessed global capitalism on trial.

Global conglomerates can only operate as they do because of a framework designed to allow them to capture or co-opt governments and regulatory bodies and to use the WTO and bilateral trade deals to lever influence. As Jason Hickel notes in his book (previously referred to), old-style colonialism may have gone but governments in the Global North and its corporations have found new ways to assert dominance via leveraging aid, market access and ‘philanthropic’ interventions to force lower income countries to do what they want.

The World Bank’s ‘Enabling the Business of Agriculture’ and its ongoing commitment to an unjust model of globalisation is an example of this and a recipe for further plunder and the concentration of power and wealth in the hands of the few.

Brazil and Indonesia have subsidised private corporations to effectively destroy the environment through their practices. Canada and the UK are working with the GMO biotech sector to facilitate its needs. And India is facilitating the destruction of its agrarian base according to World Bank directives for the benefit of the likes of Corteva and Cargill.

The TRIPS Agreement, written by Monsanto, and the WTO Agreement on Agriculture, written by Cargill, was key to a new era of corporate imperialism. It came as little surprise that in 2013 India’s then Agriculture Minister Sharad Pawar accused US companies of derailing the nation’s oil seeds production programme.

Powerful corporations continue to regard themselves as the owners of people, the planet and the environment and as having the right – enshrined in laws and agreements they wrote – to exploit and devastate for commercial gain.

Partnership or co-option?

It was noticeable during a debate on food and agriculture at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow that there was much talk about transforming the food system through partnerships and agreements. Fine-sounding stuff, especially when the role of agroecology and regenerative farming was mentioned.

However, if, for instance, the interests you hope to form partnerships with are coercing countries to eradicate their essential buffer food stocks then bid for such food on the global market with US dollars (as in India) or are lobbying for the enclosure of seeds through patents (as in Africa and elsewhere), then surely this deliberate deepening of dependency should be challenged; otherwise ‘partnership’ really means co-option.

Similarly, the UN Food Systems Summit (UNFSS) that took place during September in New York was little more than an enabler of corporate needs. The UNFSS was founded on a partnership between the UN and the World Economic Forum and was disproportionately influenced by corporate actors.

Those granted a pivotal role at the UNFSS support industrial food systems that promote ultra-processed foods, deforestation, industrial livestock production, intensive pesticide use and commodity crop monocultures, all of which cause soil deterioration, water contamination and irreversible impacts on biodiversity and human health. And this will continue as long as the environmental effects can be ‘offset’ or these practices can be twisted on the basis of them somehow being ‘climate-friendly’.

Critics of the UNFSS offer genuine alternatives to the prevailing food system. In doing so, they also provide genuine solutions to climate-related issues and food injustice based on notions of food sovereignty, localisation and a system of food cultivation deriving from agroecological principles and practices. Something which people who organised the climate summit in Glasgow would do well to bear in mind.

Current greenwashed policies are being sold by tugging at the emotional heartstrings of the public. This green agenda, with its lexicon of ‘sustainability’, ‘carbon neutrality’, ‘net-zero’ and doom-laden forecasts, is part of a programme that seeks to restructure capitalism, to create new investment markets and instruments and to return the system to viable levels of profitability.