The depth of anti-humanist sentiment related by Douglas Rushkoff in his latest book, Survival of the Richest, is harrowing and illuminating.

By Chris Barsanti

Source: PopMatters

Some things can be horrifying even if unsurprising. One such moment is the opening anecdote in Douglas Rushkoff’s Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires. In 2017, Rushkoff was paid an exorbitant fee to travel to a remote high-end resort where (he thought) he would do his usual thing: Talk about the future to investment bankers looking for a way to game the next trend.

What happened was far stranger. Rather than give a speech, Rushkoff sat at a conference room table with five fantastically rich guys from “the upper echelon of the tech investing and hedge fund world” and tried to answer their questions about how they could survive the impending apocalypse.

The scene is comical, in a Dr. Strangelove way. Assuming the world is racing toward an inevitable societal collapse they called “the Event”, the men thought it best to talk survival tactics with a self-described “Marxist media theorist” and professor at Queens/CUNY. Rather than acting like masters of the universe, they were nervous about being caught out when the Event came. They worried whether New Zealand or Alaska was the right location for their doomsday bunker; could their security guards keep the hungry mobs at bay; if an all-robot staff could be better. Rushkoff explains what seemed to lie behind these unnamed One Percenter preppers’ anxieties:

Taking their cue from Tesla founder Elon Musk colonizing Mars, Palantir’s Peter Thiel reversing the aging process, or artificial intelligence developers Sam Altman and Ray Kurzweil uploading their minds into supercomputers, they were preparing for a digital future that had less to do with making the world a better place than it did with transcending the human condition altogether. Their extreme wealth and privilege served only to make them obsessed with insulating themselves from the very real and present danger of climate change, rising sea levels, mass migrations, global pandemics, nativist panic, and resource depletion. For them, the future of technology is about only one thing: escape from the rest of us.– Douglass Rushkoff

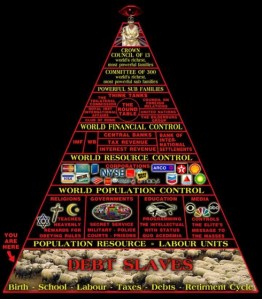

Rushkoff calls this thinking “the Mindset”. He defines it as an “atheistic and materialistic scientism” that launders a desire for control and conquest through quasi-religious adherence to digital code and the power of the market. Expanding on his original article from 2018 (Medium)—which ironically led to his being swamped by requests from disaster-related industries to get in touch with the anonymous five they thought needed their services—Rushkoff spends the rest of Survival of the Richest explaining where the Mindset came from, how dangerous it is, and what he thinks should replace it.

Nothing that Rushkoff writes in this clipped, angry book should surprise most readers. Nobody who has spent any time tracking the pronouncements and feuds of the more futurist-minded tech elites would think many had a high opinion of or interest in improving the daily lot of carbon-based life forms. Though predictable and at times a bit too broadly defined, the depth of anti-humanist sentiment related by Rushkoff is still harrowing and illuminating.

The phenomenon of powerful men thinking themselves separate from the great unwashed and unbound by common morality is as old as human history. Although this of-the-moment book contains little context dating back more than three decades, Rushkoff does not try to claim everything about the Mindset is new. He points instead to how illogical power fantasies have merged with an Ayn Randian cult of the solitary hero and been nurtured by the Web’s seductive capacity for self-aggrandizing mythmaking. Given how much he may have contributed to those seductions, he is the right messenger.

Among the first public intellectuals to grapple seriously with the digital revolution as it washed over society in the 1990s, Rushkoff remains a go-to expert for Internet prognostication. Unlike many tech evangelizers, though, he later had second thoughts. Some of the more revealing sections in Survival of the Richest come from when the author turns his focus on himself.

Readers of a mindset will likely feel a certain wistfulness as Rushkoff writes about the early punk years of cyberspace. Just as underground music was bursting into the mainstream and indie bands were making real money, outlaw hackers were suddenly at the forefront of a technological revolution. In 1994, Rushkoff published two books: The GenX Reader, a heady anthology of alt-cultural tropes (part of the Slacker screenplay, Dan Clowes and Peter Bagge comics) that could already see the commodification of generational rebellion to come; and Cyberia, a quasi-utopian paean about the psychedelia-inspired confluence of programmers, Deadheads, libertarians, Wiccans, and ravers who seemed to be leading the nascent Web towards a consciousness- and freedom-expanding future. The 1996 “Declaration of Independence of Cyberspace,” announced ironically enough at the first ever World Economic Forum in Davos, proclaimed a borderless world where governments had no sovereignty.

Rushkoff looks back now with clearer eyes:

Deregulation sounded good at the time. We were just ravers and cyberpunks, paranoid about the government arresting us for drugs … We didn’t realize that banishing the government from the internet would create a free zone for corporate colonization. We hadn’t yet discovered that government and business balance each other out—a bit like fungus and bacteria. Get rid of one, and the other runs rampant.

In Rushkoff’s cultural history, the experimental tribal ethos of the Web’s heady early days was co-opted by business interests who saw a new frontier to monetize; less Mondo 2000, more AOL CD-ROMs. Online libertarianism seemed to evolve from a confederacy of rule-breaking rebels and pioneers to anger-prone grumps so dissatisfied with their fellow man that they started planning unintentionally funny “seasteading” ocean communities, taking their toys and leaving. Wealthy futurists imagine uploading themselves onto a cloud server, revealing a depressingly simplistic view of human consciousness and a grand view of themselves as transcendent immortals. As technology and behavioral science became more finely tooled at predicting consumer behavior, it also exacerbates hate and loneliness, assisting the all-too-easy COVID-19 pandemic pivot to increasingly tech-mediated relationships.

For the Mindset’s “tech titans and billionaire inventors”, per Rushkoff, there is no problem that technology cannot solve. And the problems are often human in form. Suppose that were true, and the world was spiraling towards a collapse (which the online tools superpowered by elites could be accelerating). In that case, the believers might wonder, why not use technology to scarper off to their Bond villain bunkers?

Rushkoff’s critique expands from what he calls this amoral “sociopathic” attitude toward the state of capitalism. Combining the digital-communitarian ethos of Cory Doctorow with the acerbic skepticism of Naomi Klein, Rushkoff does not trust that a more enlightened kind of capitalism can save the world. His argument against eternal economic growth has merit. But Rushkoff is on firmer ground when defining technological-sociological phenomena like the Mindset. That is not to say there is no case for a more sustainable economy, but Rushkoff breezes too quickly past the challenges resulting from that massive transition. Being necessary does not make a thing easy.

As with many jeremiads of this kind, Survival of the Richest loses some of its impact when delivering suggestions for how to push back (don’t give in to the inevitability of doom, buy local, fight for anti-monopoly laws). That is partly because it is difficult for them to seem equal to the magnitude of the problem. But for Rushkoff, the smallness of the solutions is part of the point: “We can still be individuals; we just need to define our sense of self a bit differently than the algorithms do.”