By Erik Lindberg

Source: Resilience

To have lost the godlike conceit that we may do what we will, and not to have acquired a homely zest for doing what we can, shows a grandeur of temper which cannot be objected to in the abstract, for it denotes a mind that, though disappointed, foreswears compromise. But, if congenial to philosophy, it is apt to be dangerous to the commonwealth. –Thomas Hardy

We have the choice of three paths into the future. But choice is probably not the right word, for historical change is, at its most orderly, the result of action and reaction and reaction to that. The word paths may in the same way be too tidy, for we are more likely to go crashing into the thickets than to follow the marked and warn paths that inhabit our imagination.

But here, in this brief exercise, I’m thinking about moral and cognitive maps and the way we might direct our ideals. Perhaps, then, I may be forgiven these simplifications. I am not making predictions about how the future might actually unfold; rather, I’m imagining the directions towards which we might cast our highest aspirations.

1) The Arc of History Bends towards Progress

Path 1 might be called the Liberal[i] Choice. It follows the idea that a just and secure global order requires basic equality among all humans and all nations. But equality is only a half of it: as important as the ideal of equality to the Liberal vision is the way equality might be achieved—namely by way of economic growth and increased overall wealth, which (the Liberal half-assumes and half-hopes) will be spread more equitably in the coming decades, allowing the impoverished to increase their standard of living faster than the already-prosperous will. The Liberal vision imagines that Western and industrialized standards of living might be spread across the globe so that all people might enjoy electricity, paved roads, internet connection, urban anonymity, and (almost as human right) relief from the most difficult aspects of manual labor or subsistence farming, with the opportunity to become educated and free from the limiting prejudices of traditional societies. It sees mobility, individualism, and choice as the hallmarks of this just and equitable society[ii], and imagines humanity becoming more cosmopolitan, tolerant, and secular, while earning its daily bread through endeavors deemed creative according to middle class values.[iii]

Liberals sometimes appreciate the link between economic growth or growing overall prosperity, on the one hand, and a tolerant and cosmopolitan global order, on the other. This link is more implied than discussed (though it is also sometimes difficult to find policy makers discussing anything but economic growth). But Liberals are mistaken to assume, as they often do, that education, mobility, and secular tolerance (along with the embrace of “free markets” and the cultivation of an entrepreneurial spirit) have themselves created economic growth and growing prosperity, and are wrong to imagine (as they do in a vague and image-filled sort of way) that Africa, Asia, and South America might join the Euro-American prosperous middle class once they free themselves from the train of ancient and venerable prejudices[iv] that stunt their progress. Western prosperity, after all, is not a pretty thing if you look into it too much.

Liberals are likewise mistaken to believe that tolerance or peacefulness is a simple state of mind, or that they might be projected effectively with bumper-stickers, protest signs, and earth-tone sweaters, or that a Clinton regime would have somehow been less bloody than a Trump one, or, cum Sanders, that our unparalleled levels of consumption (i.e. prosperity) does not in fact require a menacing global military presence in addition to the manipulations of a multi-billion dollar marketing industry. Peace does not come from virtuous mental states; it is instead the product of a delicate sociological balance that is absent in many parts of the world and that is disappearing in traditionally Liberal nations—and often for reasons that Liberals are hard-pressed to explain except by declaring that we need more Liberalism and its states of mind, backed by vague and increasingly incoherent policy objectives. The tepid enthusiasm for the center left (in the U.S. last autumn or in France today[v]) may be a symptom of its incoherent and increasingly implausible vision.

2. Power Realism[vi]

As I write these words, geo-political analysts are envisioning Russia and the United States on the verge of a new cold war. Perhaps. Regardless of how heated it becomes, the nature of this new East-West opposition, especially when compared to the previous one, is well worth noting. Not only has the past ideological divide mainly disappeared, we might instead be struck by the way these global rivals are coming to resemble each other. Never mind the possible scandals and whatever is at their root, the arrival of Trump represents what might hyperbolically be called Russianization of the U.S. Like Putin, after all, Trump does not operate according to a myth of emancipation, but only according to the pursuit of national power. Trump may not share Putin’s understanding that the source of power lies in resources (but perhaps he does), but his actions and his economic assumptions seem to concur with this view, as does the operating outlook that statecraft should work to corner as many remaining resources as possible.[vii]

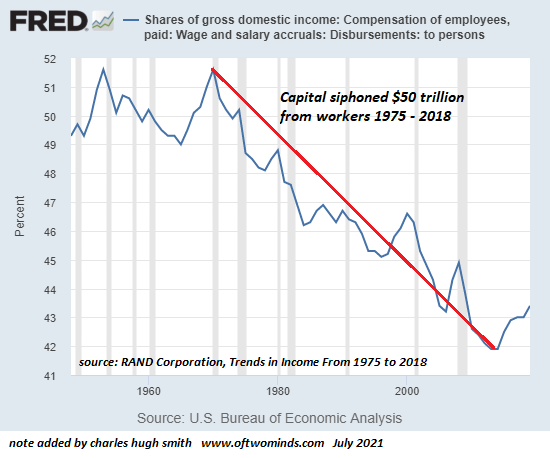

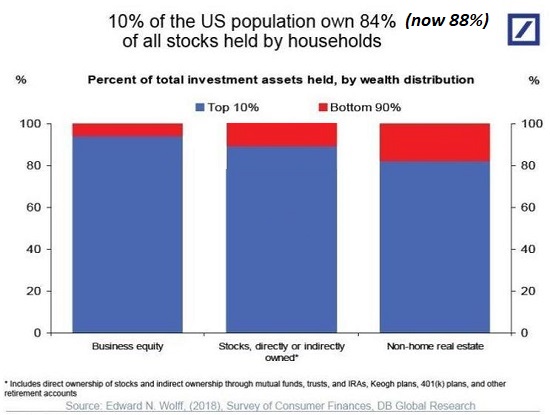

Meanwhile, the rise of Trump and Trumpism in the U.S., as well as similar movements and sentiments in Western Europe, should in fact be attributed to the failure of the Liberal path and the decline of global economic growth—the end of one version of the “delicate sociological balance,” and the only version most of us can imagine (that gap in imagination is why I write). Long term stagnation and the end of expansive bourgeois hope have worked to weaponize the “me first” attitude: under a neo-Liberal world order, self-interest was supposed to lead to a rising tide, but Power Realists have little need for any such benevolent apologia. Now harnessed by belligerent nationalists, this attitude of economic competition is more and more likely to accept wide-scale inequality and is instead concerned to be on the winning side of a winner-take-all competition over the world’s remaining resources and comparative advantages.[viii]

To put this last point in another way, relatively few people have, at least until very recently, been willing to openly and consciously embrace the me-first belief-system of Power Realism, absent any accompanying narrative of emancipation. But most of the West’s middle-class has long wanted, expected, and demanded in a way that effectively “chooses” a path of Power Realism and the international bullying it requires–far sooner, at least, than it would veer towards a lowering of any such demand and expectations.

Dead Ends

Liberals and Power Realists equally see the dead-end that the opposing path leads to. But both are equally blind to, or at least resignedly sanguine about, the dead-end that their own path leads to. Liberals correctly understand that the widespread global inequality that Power Realists appear ready to tolerate will lead to permanent war and conflict and perpetual assaults on national security by those left behind.

Meanwhile, Power Realists seem to understand[ix] or sense (though they don’t openly articulate it in public) that the Liberal vision of 3% economic growth into perpetuity is a farce and a fantasy, and that the whole world will never live like we in Europe or America do.[x] Our way of life may in fact depend, in the end, on the walls and borders that Liberals decry on “moral” grounds. Insularity and defensiveness may be the required dispensation, as we choose our way of life over global equality. Power Realists also intuit that most Liberals can be turned into Power Realists under increasingly common economic conditions. The mere loss of expansive prospects is enough to turn many an Obama supporter into a Trump supporter. Minor economic decline, even the absence of economic expansion, was all that it took. Except for those prepared to blaze a new trail into uninhabited ideological wilds, Path 1 usually leads to Path 2 with the onset of only moderate duress. Liberals mistakenly believe that hate is a prime driver[xi] of inequality or discrimination, and that it might be purged from the heart with an enlightened dose of Liberal hope. This may occasionally be true, but hate is more the symptom and might inflict itself on anyone who has suffered repeated humiliations or degradation—or even the mere loss of unquestioned privilege.

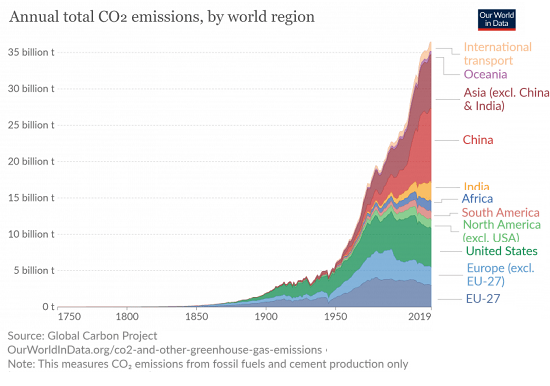

Our current political conflicts, both domestic and international, can therefore be largely attributed to our adherence to these two merging paths—especially if we take into account our destabilized climate and resulting droughts in places like Syria and Somalia, in addition to all the other ways nations and peoples jostle for power and advantage. Climate chaos and the resulting political chaos will be the most notable legacy of Liberal growth and the Power Realism that has begun to cruelly manage it.[xii]

Political conflicts are almost always presented as a battle of ideals (as with the American choice of freedom over tyranny during WWII[xiii]) with the implied presumption that we might choose peace and equality as discrete policies or national values, unconnected from our economic and consumptive being- in-the-world. According to this battle of ideals, then, one side sees the world divided between a coalition of enlightenment, empathy, tolerance, and inclusion, opposed to uninformed bigotry and short-sighted selfishness. As a bumper sticker I saw the other day smugly put it, “I think, therefore I’m Liberal.” The other side sees a line dividing steadfast, uncompromising faithfulness and resolve from naïve and undiscerning acceptance and compromise, a line between strength and weakness, between realism and soft-headed idealism.

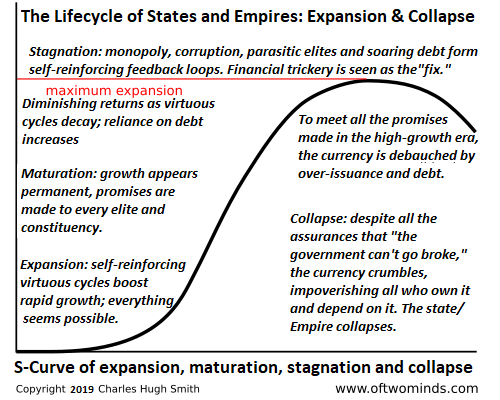

But our current global change and conflicts are better understood with concepts drawn from sociology or anthropology than from self-reassuring talking-points. A stable social order requires what we might refer to as consent or “buy in,” perhaps a lessening of the inevitable tension between civilization and its discontents into a stable détente. During the short Pax Americana, this consent has been purchased with the promise of expanding prospects for all, fueled by an economy that devoured its own resource base in a way that renders its continuation impossible. The Liberal order replaced social bonds with growing possibility,[xiv] and required for its maintenance the fulfilled promise that every year would provide more and that every generation could expect distinct material improvements. [xv] This order had no plan for material contraction or the onset of limits, other than to declare in the face of reality that there are no limits to growth.

This lack of a plan for stasis, let alone degrowth, might explain the demise of what so many Liberals believed to be the arc of history. We maintain our acquisitive and competitive values and the primacy of individual liberty. But in the absence of the growth and opportunity that purchased consent, trust horizons shrink and we see a turn towards group identity (as an alternative to participation in some imaginary global civilization) and begin an openly hostile scramble for remaining pockets of wealth and privilege (in the absence of the promise that everyone might have more forever). Globalist buy-in has no dependable currency.

Picture global conflict not as the fight between liberals and conservatives, between the enlightened and the ignorant, between moderates and fundamentalists. Picture, instead, penniless children with their noses pressed against the candy store window, while entitled brats stuff their pockets full of unearned loot.[xvi] Forget ideals and instead imagine repeated humiliation, envy, and frustration, broken promises and abortive ideals. It is not some obscure “ideology of hate” or an unexplained failure of moderate pro-Western policies according to which the explosive vest is strapped on. Nor can we explain as simple sexism the way Donald Trump’s gropings (and so much else) were so widely forgiven. Far stronger than we tend to accept is the desire for purpose and belonging, and the desperate (and sometimes violent) search for renewed social bonds when the limitless world of boundless and bondless expansion flounders on the shoals of a finite planet. We once lived in a world when there was little disbelief in face of the comforting contradiction that we might all somehow “get ahead.” Now it is clear that only a few can actually do so. It is this realization that creates nationalism, Brexit, right wing populism, hatred of immigrants, or “America First.”

3. A Third Way

The Liberal Dream is dying because the planet was never infinite and our potential never limitless–not because some bad-guy ignoramuses somehow got the upper hand. A social order could never be maintained for long by the promise of more every year, while the tide can only rise so high before it washes all good fortune away. The most direct and facile, yet brutal and likely, antithesis of Liberal Growthism is personified by Trump, Putin, or Le Pen today, Hitler, Mussolini and Franco in years past,[xvii] and can only lead to war and repression.[xviii] Such rulers are what arise at the onset of Liberalism’s decline. But they offer no real solution, only a quick reordering of hope and expectation into anger and hate—an ordering nonetheless. Intoxicated by the thrill of an arms race, Power Realists ignore the fact that the oppression and forceful repression of at least half the world’s population is unsustainable, and that the immiseration it spreads will eventually inflict us all. Liberals know this and are aghast at the rise of these values. But they, in turn, are all too ready to ignore the fact that Liberal hope requires unsustainable growth and insulate themselves from the realization that our global climate crisis was not caused by nationalism or the greed of someone else. It was caused by this same growth, which continues to demand levels of goods and services that are bringing our ecological systems to the point of collapse.

There is of course a third choice—one that is simple yet mainly unthinkable. It sees with heart stopping clarity the dead-end towards which the other two paths lead and has math, science, and even hard-headed economic analysis[xix] on its side, not to mention a pretty solid interpretation of most of the world’s major religions. But it is a choice that few appear prepared to adopt, even entertain. It accepts the view that a secure and stable global order must be a relatively egalitarian one—that, according to one idiom, all God’s children deserve a fair share of the Earth’s bounty. It understands that the 5% of the global population that the United States accounts for cannot continue to use a quarter or a fifth of the world’s energy and natural resources while emitting a similar proportion of carbon dioxide.

And here is where this path parts ways from any of the views normally deemed fit for polite company: for it does not believe that the rest of the world should be brought to our level; that would be ecological suicide. For if the whole world were to live like Americans we would need an additional four to six Earth’s to supply the required energy and natural resources, and to absorb our terrible waste. A transition to wind and solar power does not substantially change this equation, nor do all the most far-flung efficiencies that anyone might realistically imagine.

The path according upon which humanity has a chance to find a just and sustainable world requires what is unthinkable yet mathematically impeachable and morally imperative: that we in America and Europe live more like African villagers, Indian subsistence farmers, and South American peasants.[xx] They must become our models for the triumph of human dignity and justice, not to mention sustainability. We, who have the appearance, at least, of a choice, must choose this sort of radical simplicity, embrace the hard work and the community interdependence, and abandon dreams that we might live without limits and be or do anything we can imagine (that godlike conceit was forged under the illusion that we have an infinite universe at our disposal[xxi]).

This will never happen you say. It is unrealistic. People will never give up privilege unless they have to.[xxii] Congratulations: you have just chosen Path 2. But true enough, I can’t disagree, this skepticism is probably warranted, especially if the limits of human aspiration are to be pragmatic and strategic, if you can’t hope beyond the current political parties and already established life-paths for middle class people. For there is no clear path from where we are to a world of radically simple sustainability, except the one paved with cataclysmic violence and bloodshed, in which we will eventually be forcefully taken to our knees.[xxiii]

But we might still stand up and declare, “this is the right path, this is what I support, this is where I will throw my energy.” There is no reason why we must continue to choose Path 1 or Path 2, or accept it–no reason why we must continue to pretend that our way of life or our side of the ideological divide (give or take a few ideological tweaks) is just and sustainable. There is no reason why we should continue to give our consent to the maintenance of either growth or inequality. Let us openly and loudly declare our commitment to our own eventual material poverty, and in this declaration find moral and spiritual wealth. Let us begin to proclaim the unthinkable and think it every day.

[i] By Liberals I mean philosophical Liberals, which has generally included many who are considered political conservatives. Ronald Reagan was as much a Liberal as Bernie Sanders. Donald Trump, however, may not be a Liberal.

[ii] To borrow Chris Smaje’s term, Liberals are “solutionist” when it comes to freedom and choice, unable to see that there are in it advantages and disadvantages, payoffs and collateral damage.

[iii] Where apps are “creative” but managing erosion on a hardscrabble farm is not.

[iv] And accept that loan from the IMF along with the accompanying “restructuring” and “reforms.

[v] Does anyone really embrace the vision of a Clinton or a Macron? Or is it just a safe alternative to the alternative?

[vi] I am not suggesting that “Power Realists” are across the board more “realistic.”

[vii]http://www.resilience.org/stories/2017-01-24/donald-trump-and-economic-growth-a-brief-interregnum-on-growthism/

[viii] http://www.resilience.org/stories/2017-01-24/donald-trump-and-economic-growth-a-brief-interregnum-on-growthism/

[ix] I’m completely not sure about this. Power Realists may be as Growthist as neo-liberals and certainly trumpet the ideals of economic growth. But their rise, I would assert without much qualification, has been made possible by the ending of growth and their policies are suited to the end of a Growthist order.

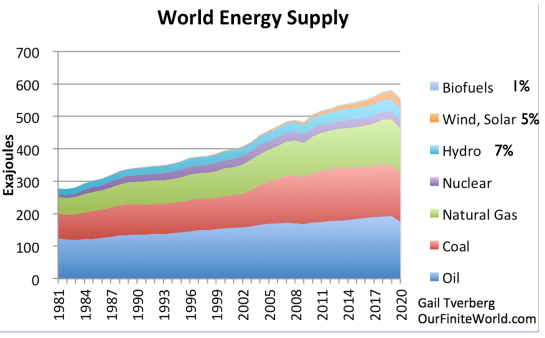

[x] It is with some weariness that I feel compelled to provide evidence for this conclusion. Either the idea that the Earth can provide enough resources for the rest of the world to live like us, or the idea that exponential growth remains a viable plan for the future, on their own, belie any mathematical conclusions. But the Liberal vision requires both. A true Liberal paradise would require that we maintain 3% or so economic growth in the industrialized world, while the “developing” world grows even faster to catch up. The main reason that this can’t work is, simply, that growth is tantamount to mass genocide followed by mass suicide. For despite ballyhooed efficiencies and alleged “decoupling” no one has figured out to create more stuff for more people without using more natural resources. There is no way to lift a 400 ton passenger airplane off the ground with a small ecological footprint or provide everyone with one-hundred horsepower personal transportation without making the planet unlivable. If everyone were to live like Americans, we would require about 6 times the current amount of things like rubber, oil, timber, concrete, and iron ore. Meanwhile 3% economic growth—the amount most Liberal economists believe is necessary to maintain our delicate sociological balance—means that the size of the economy (and the amount of natural resources it requires) will double every 23 years. That means in 56 years, the natural resource requirements would be quadruple the current level. This is not a viable path into the future. These resources simply don’t exist, and attempting to squeeze them out of our planet would make it unlivable. Past and current attempts may already have. No wonder so many pro-growth technophiles look to outer space as the solution to humanity’s alleged need for growth—which begs the very basic existential question of why so many humans see this as a better plan than the unthinkable one I suggest below. I review some of the fundamental problems of economic growth in http://www.resilience.org/stories/2017-02-22/economic-growth-a-primer/

[xi] What Jacques Derrida would have referred to as a “transcendental signifier,” a thing-in-itself, something that just is, which, like “evil,” not only needs no further explanation, but in fact shuns it.

[xii] As Michael Klare has recently noted more people are on the brink of starvation now than at any time since WWII. http://www.resilience.org/stories/2017-04-21/climate-change-genocide/

[xiii] This “choice” is far better described with that word, and with the notion of “ideals,” than anything we encounter today. However, the clean narrative of good vs evil has nevertheless been simplified, with the relation of national interests to resources and empire being erased from the picture, or perhaps overshadowed by the atrocities.

[xiv] http://www.resilience.org/stories/2017-01-17/the-growthist-self-growthism-part-3/

[xv] http://www.resilience.org/stories/2016-01-11/a-geo-physis-of-freedom/

[xvi] And then picture these same entitled brats with their noses pressed up against another window on some other day.

[xvii] As the US Joint Forces Command concluded in 2010, “A severe energy crunch is inevitable without a massive expansion of production and refining capacity. While it is difficult to predict precisely what economic, political, and strategic effects such a shortfall might produce, it surely would reduce the prospects for growth in both the developing and developed worlds. Such an economic slowdown would exacerbate other unresolved tensions, push fragile and failing states further down the path toward collapse, and perhaps have serious economic impact on both China and India. At best, it would lead to periods of harsh economic adjustment. To what extent conservation measures, investments in alternative energy production, and efforts to expand petroleum production from tar sands and shale would mitigate such a period of adjustment is difficult to predict. One should not forget that the Great Depression spawned a number of totalitarian regimes that sought economic prosperity for their nations by ruthless conquest.” https://fas.org/man/eprint/joe2010.pdf, p.22 (emphasis added).

[xviii] Someone like Reagan is of great historical interest, what with his attempt to create a synthesis of the two, reflected in his soaring rhetoric, but paid for with massive debt and the strategic use of populist hate.

[xix] I am not, of course, referring to most mainstream economic analysis. Economics as a discipline has been charged mainly with the task of figuring out how to grow the economy regardless of the consequences or the possibility. By “hard-headed” I am thinking of the few economists who have escaped this Growthist ideology and follow what Charles Hall and Kent Klitgaard refer to as “biophysical economics.”

[xx] This point has been made most poignantly by Chris Smaje. If you haven’t been reading his work, start now. It’s among the most interesting in the “deep sustainability” world. I need to further note that this current essay was motivated by Chris’s “Article 51” where he writes: “I’ve been accused before of irresponsibly wishing to lower the standard of living in the wealthier countries to the level of common misery experienced by humankind in general in relation to my remarks on immigration. On reflection, I’m happy to embrace that accusation, if I’m allowed a few extra lines of defence. I embrace it because, well, what’s the alternative? Historically, capitalist ideology has justified itself with aqueous metaphors of downward trickling and upwardly rising tides that benefit all. It’s become clear that these are mirages. So the argument against a fair global spread of economic resources then boils down essentially to the devil take the hindmost. I can’t justify that to myself ethically, and in any case I think that road leads to a still deeper mire of global misery.” http://www.resilience.org/stories/2017-03-28/article-51/

Smaje consistently condenses complicated issues into digestible form without sacrificing the complexity. I’m trying to recondense some of his thoughts—or my take on them—into my own idiom and may be justly accused of adding little to what he has already said.

[xxi] It’s a nice sentiment, and it’s everywhere. The prevailing “moral” of 90% of the movies currently made for 5 year olds is that they can be who or whatever they want, if they only follow their dreams and “be themselves.” I get where this is coming from, and can glimpse the cost of abandoning this fiction. But we need to start considering the fact that it just isn’t true, and certainly can’t be, at least as currently understood, for 6 or 7 or 8 billion people. It might be possible, for a while, for half a billion or so. And then they are likely to kick and scream and pout when the promise turns out to have been false.

[xxii] And the ecological limits of the world will never appear to us as a “have to,” even though they most certainly are.

[xxiii] There are of course brave pioneers who have beaten a track in this direction—ones like Jim Merkel. But the problem of a whole-society or whole-system transition has yet to be solved.