By Michael Grasso

Source: We Are the Mutants

k-punk

By Mark Fisher

Foreword by Simon Reynolds, Edited by Darren Ambrose

Repeater Books, 2018

A little over two years ago, theorist and cultural critic Mark Fisher took his own life at the age of 48. I remember feeling numb at hearing the news; not out of sadness but more a sense of deja vu, of familiarity. I’d been through something similar already with David Foster Wallace’s suicide back in 2008; his Infinite Jest (1996) was one of the single most searing, searching moral indictments of the post-Cold War social and political order in the West, and a tremendously important work to me personally. Fisher toiled in very much the same fields in his writings. Both men had used their own struggles with depression (and in Wallace’s case, addiction) to fuel their insights into a world order that had run out of promise, of hope for the future. Wallace died two months before Barack Obama was elected, in the midst of the 2008 financial crisis; Fisher immediately after the election of Donald Trump. One American election offered (misplaced) hope, the other, a terminal kind of despair.

Over the past year or so I’ve also had the opportunity, while finishing my Master’s degree, to delve deeply into the work of cultural critic Walter Benjamin, who came to intellectual maturity in the Weimar Republic and found himself an exile with the rise of the Nazis in 1933. Like Wallace and Fisher, Benjamin used the cultural environment around him to help explain the world, to make sense of the turmoil that was roiling the once-orderly social order around him. Benjamin also killed himself, as he fled from the Nazi invasion of France in 1940 at the age of 48, just like Fisher. The parallels between all three men, to my mind, were uncanny. In the end, I feel the same thing got all three of these men: the encroaching feeling of dread at observing a world that had spun off its axis, beyond their ability to explain it.

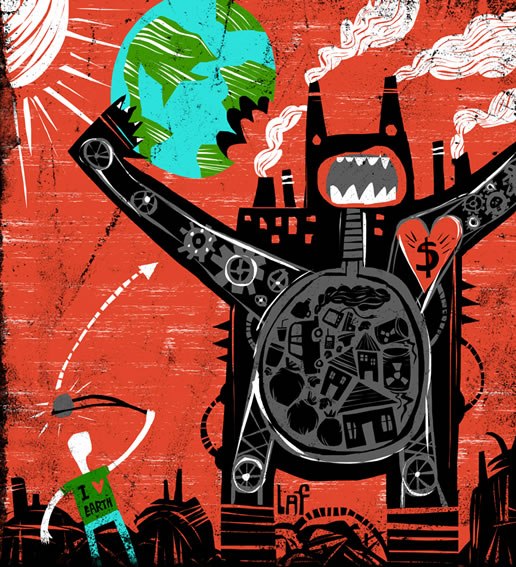

I offer all this as a preface to my review of Mark Fisher’s collected online and unpublished writings, k-punk (Repeater Books, 2018), because I find myself thinking more often these days about the void of Fisher’s loss rather than the wealth of writings that he gave us while he was alive. And I feel like my despair essentially misunderstands what Mark Fisher was all about. The overwhelming feeling of most of the writings collected in k-punk is one of utter joy, whether it’s in celebrating a lost piece of media that Fisher wants us to know about, or his just and righteous delight in explaining exactly what late capitalism is doing to all of us.

A couple of years ago, my podcast partner Rob MacDougall and I had occasion to talk about the intellectual history of defining and preventing sexual harassment in the workplace for our podcast about WKRP in Cincinnati. And I’ll never forget the way he explained how clearly and uncompromisingly that defining a social problem can be the most important first step in combating it. He said, “Language is technology. Until you can name [something], you can’t get at it.” And I think that’s the legacy of Mark Fisher in a lot of ways. He gave us new terms—“pulp modernism,” “the precariat,” “hauntology,” “capitalist realism,” “acid communism”—that helped define not only our problems but our collective dreams for a better world. Like Benjamin before him, Fisher used his precise and profoundly moral observations of the world around him to give us a vocabulary to understand and express what is being done to us and how we can find our way out of it.

First things first: k-punk is a monster. Repeater Books has collected Fisher’s blog posts and unpublished writings in a massive 800-page tome. Given that the average length of one of these essays is about 3-4 pages, what you end up with is a bewilderingly encyclopedic collection of Fisher’s thoughts on seemingly everything. The conversion of once-hyperlink-laden web text to paper is sometimes jarring—the editor Darren Ambrose has done yeoman work in providing footnotes to mark where links to other bloggers and commenters once lay—but the reader almost never feels lost in figuring out what Fisher was trying to say. The foreword is by Fisher’s contemporary and friend, the music critic Simon Reynolds, whose seminal 2005 work on post-punk, Rip It Up and Start Again, is a favorite of mine. The same author’s 2011 Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past was, like Fisher’s work, a major inspiration for my own Master’s capstone project on nostalgia and its use in museums. Reynolds’ foreword is not only a heartfelt and deeply touching tribute to Fisher’s life and work, it also illustrates well the cultural milieu in which both men worked in the early part of this century. Getting to know someone better by reading their blog everyday is a deeply familiar mode to me and many members of my generation, and here Reynolds nails the somewhat uncanny feeling of getting to be best friends with someone you’ve only hung out with a few times in person. Probably it will be less strange for the generations who come after us. I do admit stifling a chuckle as one of the first essays in this paperback collection is a “tag five friends” meme; seeing such an essentially “online” phenomenon in print, in an esteemed cultural critic’s essay collection no less, would probably be considered “weird” in the Fisherian “weird/eerie” schema: an intruder from Outside whose alien presence inflects its surroundings.

In his foreword, Reynolds dubs Fisher a member of a disappearing breed: “the music critic as prophet.” Both Reynolds and Fisher came of age in the golden era of British publications like the NME, which treated its readers with a modicum of sophistication and intellectual respect. British music critics in the 1980s were never afraid to throw in references to contemporary political philosophers and cultural critics from the world of academia, nor were they reluctant to blur the lines between artist and critic. Fisher himself offers tribute to one of these writer-artists in “Choose Your Weapons,” an essay focusing on NME writer and Art of Noise member/ZTT Records co-founder Paul Morley, as well as his fellow NME writer Ian Penman. Reynolds sees Fisher as the clear heir to this type of rock journalist; Fisher even had his own musical group in the early 1990s, D-Generation, which peppered press releases and music with references to cultural theory.

As mentioned above and in my earlier piece on him, Fisher was never afraid to unearth a piece of forgotten media from his childhood or adolescence for examination in the cold light of our present late capitalism. His mourning for the loss of risk-taking on the part of the gatekeepers at public broadcasters such as the BBC is well-known. (I highly recommend the essay “Precarity and Paternalism” in k-punk for Fisher’s breathtaking rhetorical link between the blandness of pop culture today and the burning down of the public sphere under neoliberalism.) But what k-punk puts forth clearly (and Reynolds makes clear in his foreword) is that Fisher was never solely a backwards-looking critic. In these essays you can see him fully engaged in the contemporary cultural scene in a way that can sometimes get lost in his reputation as “the hauntology guy.” I found Fisher’s recuperation of Donnie Darko director Richard Kelly’s odd little Twilight Zone riff from 2009, The Box, to be downright essential in explaining why I liked it so much but couldn’t articulate why at the time. Ironically, Fisher avers that it is a rare piece of American hauntology (an aesthetic I’ve been desperately trying to quantify here at We Are the Mutants), with Kelly exploring the legacy of his NASA employee dad during NASA’s own final years of glory as a public agency (the late ’70s era of the Viking and Voyager probes) before the ultimately doomed Shuttle program. As someone who only gave the k-punk blog a cursory look prior to Fisher’s death, being far more familiar with his published writings, reading Fisher on the Christopher Nolan Batman trilogy or on contemporary television series that I watched from the beginning, like Breaking Bad and The Americans, hit me in that same Fisherian-weird way.

Even though the essays in the k-punk collection are organized by content type—reviews of books, music, television/film, political writings, interviews—it’s easy to note Fisher’s evolution as a writer, with each content area organized chronologically within. Perhaps this is only my prejudice, but I notice in the early years of Fisher’s k-punk posts a distinct anxiety of influence with older writers and theoreticians, out of which he eventually matures. His early-’00s work centers writers and thinkers like J.G. Ballard, Franz Kafka, Dennis Potter, even Freud and Spinoza. Slavoj Žižek also looms very large, probably for no other reason than that he was (and still is) one of the only voices engaging intelligently with the political impact of the pop culture detritus of late capitalism. But it’s in this occasional early tension with Žižek that you start to see Fisher make his own conclusions, state his own thoughts. It’s not necessarily that Fisher ever makes an explicit break with Žižek; it’s just that you see him mentioned less and less and, finally, not at all.

It was in music that Fisher saw the greatest potential for social and cultural revolution. It’s become a thoroughly lazy trope among armchair cultural critics to keep quoting that bit from Plato’s Republic about how changing a society’s music will change the society, but Fisher actually convinces the reader of that idea, in a profoundly vital and contemporary context. For Fisher, mod, glam, and to a certain extent punk all offered the working classes a chance to grab the same aristocratic glamor and glory to which the bourgeoisie had always had access. (Reading Fisher on the unearthly magical “glamour” of pop stars gets me thinking about Kieron Gillen’s “gods come to earth as pop stars” comic The Wicked + the Divine; I’d be shocked if Gillen wasn’t a k-punk reader from way back.) I personally find Fisher far stronger on post-punk. His multi-part examination of The Fall and Mark E. Smith is downright essential; I thought often while reading how much I wish Fisher could have read Richard McKenna’s Sapphire And Steel-referencing encomium to Smith. A pure love of Green Gartside of Scritti Politti and his dance-floor theoretics, so beloved by that very same theory-soaked 1980s NME, shines through in several k-punk essays. Fisher’s multiple essays on the goth aesthetic (and adjunct aesthetic movements like steampunk) are insightful, even as he holds goth at a bit of a remove as compared to post-punk and dance music. His essays on the Cure, Nick Cave, and specifically Siouxsie Sioux’s visual aesthetic from early swastika-armband-wearing punk provocateur to glittering Klimt spectacle on A Kiss in the Dreamhouse are particularly good.

And it’s here in Fisher’s music writing that we see yet another evolution, this time in three phases roughly analogous to the Marxist-Fichtean dialectic. Fisher begins with an arguably essentialist, archetypal, borderline Paglian view of the aristocratic charisma inherent in pop music; moves to a canny and earnest recognition of the purely proletarian qualities of post-punk and dance music (and the paradoxically populist power of the “public information” aesthetic of hauntological music); and then shifts to an eventual synthesis of these very different conceptions of music-as-liberation.

That synthesis was to be the topic of his next book, Acid Communism, the preface for which is included at the end of k-punk: Fisher was going to look back at the origin point for neoliberalism in the 1970s and pinpoint exactly where the workers’ movement and the left had begun to lose the battle for power. Through a re-examination of the 1960s New Left under thinkers such as Herbert Marcuse, Fisher locates the real revolutionary promise and potential in the bewildering flowering of popular culture that occurred in the ’60s, as well as the profound societal change that this revolution in culture propelled. “Mass culture—and music culture in particular—was a terrain of struggle rather than a dominion of capital,” Fisher notes. The true conflict of workers’ leftism vs. neoliberalism, Fisher argued, happened nearly a decade before neoliberalism’s origin point, in the struggle between the liberal Cold War orthodoxies in the West and the profoundly psychedelic movement of the youth rebelling against these staid establishment cultural tendencies. In America, of course, this series of youth movements became inexorably intertwined with resistance to the Vietnam War, perhaps to its detriment. Fisher posits instead a youth movement that worked against the assumptions of Cold War-era society on a much more elemental level. He finds much more interesting the movements where the left chafed against the High Cold War hegemony of labor-leftism in the West and indeed the very idea of work, and sees glimmers of his “acid communism” in social milieus as disparate as Paris in 1968, the British miners’ strike (aided by students) in 1972, the GM strike in Lordstown Ohio in 1972, and Bologna in 1977. The essential question asked in all these times and places: what if the revolution happens and we are in thrall to just another set of labor bureaucrats? One might answer that this actually happened with the ascension of the Baby Boomers to places of authority in the supposedly kinder, gentler, more “diverse” digital capitalism we live with today.

Obviously, virtually every bit of cultural writing that Fisher published was viewed through the prism of a leftist politics, but in the Politics and Interviews sections of k-punk, we get those politics unfiltered through any particular piece of pop culture. Here is where you see Fisher at his most passionate, his most personal, his most vital. Most important, in my mind, is his relentless insistence that capitalism kills both body and soul. While a Marxist theory of alienation is certainly nothing new, Fisher’s own personal experiences with being a member of the “precariat,” dealing with the peculiar doublethink of the purported “freedom” of the gig economy, demonstrates how the market hands us all slavery in the guise of self-actualization. And here is where Fisher’s writing intersects with his profound personal interest in public health, specifically mental health. Digital technology allows the gig worker to be relentlessly surveilled and ruthlessly “reviewed”; the disappearance of the old forms of authority and hierarchy in the workplace are distributed among one’s fellow consumers to create a web of virtual bureaucracy that creates constant cognitive dissonance and the distinct feeling that one is truly never off the job. From the ancient dream of never working to the modern reality of constantly working: Fisher thus asks us over and over if it’s any wonder we are all anxious and depressed?

It’s glaringly obvious stuff to most of us living in 2019, but again: Fisher’s moral clarity shines through and illuminates the darker corners of a world to which we’ve all slowly acquiesced. And yes, Mark Fisher did suffer from severe depression himself. One of the editorial decisions that I disagree with most is the stated decision to not include Fisher’s more “pessimistic” work from earlier in his career. Here is k-punk‘s editor Ambrose on this decision:

A very small number of early k-punk posts, e.g. on antinatalism, are excluded by virtue of the fact that they seemed wildly out of step with Mark’s overall theoretical and political development, and because they seemed to reflect a temporary enthusiasm for a dogmatic theoretical misanthropy he repudiated in his later writing and life.

You still see glimpses of this pessimism and near-nihilism in a few of the essays; a startlingly good review of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ where Fisher sees its neo-Gnostic underpinnings, or a deep intrigue with the antinatalist works of horror writer and philosopher Thomas Ligotti (who would find unexpected mass popularity with Nic Pizzolatto’s use of Ligotti in the first season of True Detective). But speaking as someone who suffers with mental illness and profound depression, let me make clear: it is absolutely reasonable to expect someone even as optimistic and positive as Fisher to occasionally look at the world with abject despair. Moreover, I believe it is more than merely reasonable, it’s necessary. To dispute or deny that anyone with a modicum of political awareness would not be occasionally nihilistically fucking depressed with the world as it is today seems a massive mistake to me.

Immediately before presenting the unfinished introduction to Acid Communism, we’re presented with two of Fisher’s most famous essays: his polemic against the contemporary left’s tendency towards ideological puritanism, “Exiting the Vampire Castle,” and his personal memoir of living (and working) with depression, “Good For Nothing.” No two pieces in this book depict the central contradictions and tensions of Fisher’s ethics and philosophy more clearly. “Vampire Castle” is, in my personal opinion, one of Fisher’s greatest missteps and the one piece of his writing where I most see a distressing tendency towards a lack of empathy for his comrades. In the essay, Fisher excoriates a certain faction of the left and its tendency to center “identity politics.” He further posits that these identity-based politics are a way in which the mechanisms of late capitalist control attempt to neuter and split the political left, a profoundly “individualistic” movement rather than one that builds cross-cultural solidarity. Fisher states that humorless scolds participating in “call-out culture” are preventing the left from building true power. Every time I go back to this essay, I initially find myself seeing some some modicum of logic in Fisher’s arguments. But then I remember how much of the modern capitalism that Fisher despised is literally built on the backs of genocide, racism, slavery, colonialism. I remember all of capitalism’s own constant essentializing and dividing of the proletariat, purely on the basis of identity, a superstructure that has systematically disenfranchised entire peoples on this globe, and ultimately I react with, “This is the kind of take that only a white guy from Britain could make.” It’s tone-deaf, destructive, and has given fuel to the worst strains of white exceptionalism and disdain for so-called “idpol” on the left in the past few years. I would argue that nothing good and quite a bit that is bad has come from it.

In fact, I wish someone would’ve told Mark how harmful this piece was. I have a feeling all it would have taken is one person—a woman, a person of color, an indigenous person, someone queer—to explain to him that while there should obviously be solidarity on the left, there are profound issues of historical materialism here that stretch back centuries, unfinished work that needs a profound upheaval and seizure of power from below (and yes, to some degree the anger and fury and the positive social knock-on effects of a “call-out culture”) to even begin to deal with restoratively. I want to believe he’d understand. It can be true that the capitalist powers-that-be love watching the left devour their own over issues that might seem personalized and “individual” to a white British man, but it can also be true that the profound historical injustices inflicted on colonized peoples the world over need to be centered in any revolutionary left solidarity. Both can be true.

And then you have “Good For Nothing,” an essay that I can say confidently has saved my life, maybe several times, since I first read it a few years ago. It is overflowing with empathy: for those of us hedged in by our class identities and made to feel inferior, uneducated, unworthy, a cog in a machine that only views us for how useful we can be to an employer or to the economy. It is a crisp distillation of every piece of personal writing Fisher ever wrote about the dehumanizing and alienating collective psychological effects of neoliberalism. Most importantly, it is a clarion call for solidarity:

For some time now, one of the most successful tactics of the ruling class has been responsibilisation. Each individual member of the subordinate class is encouraged into feeling that their poverty, lack of opportunities, or unemployment, is their fault and their fault alone. Individuals will blame themselves rather than social structures, which in any case they have been induced into believing do not really exist (they are just excuses, called upon by the weak)…

Collective depression is the result of the ruling class project of resubordination. For some time now, we have increasingly accepted the idea that we are not the kind of people who can act. This isn’t a failure of will any more than an individual depressed person can “snap themselves out of it” by “pulling their socks up.” The rebuilding of class consciousness is a formidable task indeed, one that cannot be achieved by calling upon ready-made solutions—but, in spite of what our collective depression tells us, it can be done. Inventing new forms of political involvement, reviving institutions that have become decadent, converting privatised disaffection into politicised anger: all of this can happen, and when it does, who knows what is possible?

This call for collective action on a political, economic, psychological, and even spiritual level is the voice of Mark Fisher’s that I remember and hold close to my heart every day. In every one of us there is a person worthy of respect and dignity, regardless of how “useful” we might be to a boss or a manager; in all of us a person who deserves not to live a life of misery, a person worthy of joy and music and glamour. That’s the Mark Fisher who throbs under the surfaces of nearly every one of these 800 pages. k-punk is a fitting tribute to a thinker who showed us the wonder in our past and the promise in our future, if we but remembered each other and not merely ourselves.

Michael Grasso is a Senior Editor at We Are the Mutants. He is a Bostonian, a museum professional, and a podcaster. You can read his thoughts on museums and more on Twitter at @MuseumMichael.