By Paul Levy

Source: Reality Sandwich

Almost a hundred years ago, as if peering into a crystal ball and predicting the future, spiritual teacher and clairvoyant Rudolf Steiner[1] prophesied that the most momentous event of modern times was what he referred to as the incarnation of the etheric[2] Christ. By the “etheric Christ,”[3] Steiner is referring to a modern-day version of Christ’s resurrection body, which can be conceived of as being a creative, holy and whole-making spirit that is inspiring human evolution as it operates upon the body of humanity through the collective unconscious of our species. Involving a radically new understanding of a timeless spiritual event, the etheric Christ, instead of incarnating in full-bodied physical form, is approaching via the realm of spirit—as close as this immaterial spirit can get to the threshold of the third-dimensional physical world without incarnating in materialized form. To quote Steiner, “Christ’s life will be felt in the souls of men more and more as a direct personal experience from the twentieth century onwards.”[4]

A spiritual event of the highest order, Steiner felt that the incarnation of the etheric Christ is “the most sublime human experience possible”[5] and “the greatest turning point in human evolution.”[6] In his talks, Steiner refers to the etheric Christ as “Christ in the form of an Angel.”[7] Christ himself can be seen as the primordial revelation of the archetype of the Angel (who, after all, are messengers), what is known as the “Angel Christos.” The Angel Christos is a nonlocal, atemporal spirit, existing outside of space and time, that is simultaneously immersed in, infused with—and expressing itself through—events in our world. Christ as an angel reveals itself for those who have eyes to see and ears to hear as it weaves itself, not only through the warp and woof of the flow of events comprising history, but through our souls as well.

To quote Steiner, “in the future we are not to look on the physical plane for the most important events but outside it, just as we shall have to look for Christ on His return as etheric form in the spiritual world.”[8] The most important spiritual events of any age often remain hidden from the eyes of those who are entranced in a materialistic conception of the world. It greatly behooves us to not sleep through, but rather, to consciously bear witness to what has been up until now taking place mostly unconsciously, subtly hidden beneath the mundane consciousness of our species. If this epochal spiritual event, to quote Steiner, “were to pass unnoticed, humanity would forfeit its most important possibility for evolution, thus sinking into darkness and eventual death.”[9]If the deeper spiritual process of the incarnation of the etheric Christ—“Christ in the form of an Angel”—is not understood, this potentially liberating process transforms into its opposite (into the demonic).

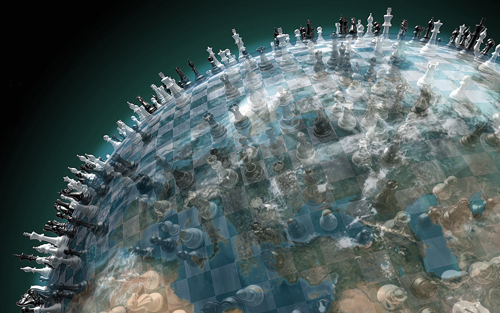

Steiner felt that the advent of the etheric Christ—the Parousia (the Second Coming)—was the greatest mystery of our time. He was of the opinion that the incarnation of the etheric Christ was the deeper spiritual process that is in-forming and giving shape to the current multi-faceted crises (and opportunities) that humanity presently faces. This is to say that the seemingly never-ending wars and conflicts that are taking place all over the globe are the shadows cast by spiritual events from a higher-dimension that are animating earthly happenings. One of the main reasons that these multiple crises are so dangerous is because their deeper spiritual source remains unrecognized.

The veil that formerly concealed the spiritual world from what we call “the real world” has fallen away, now making it possible to bear witness to how physical events are an outer, external reflection of a parallel archetypal process taking place on a spiritual plane. It is as if a spiritual dimension envelops, contains and is expressing itself through material reality. The seemingly mundane physical world and the spiritual world are revealing themselves to be indistinguishable, which is to say that life itself is resuming its revelatory function. More and more of us are beginning to recognize this; our realization is not separate from the increasing emergence of the etheric Christ. Consciousness of the restored unity between matter and spirit is not merely an awareness of this original unity, but is the very act that completes and perfects this unity.

The higher order of light encoded within the etheric Christ is bringing to light the darkness which is seemingly opposed to it, which further helps its light nature to be seen. The true radiance of the light can only be seen and appreciated in contrast to the depth of darkness it illumines. It is as if the revelation of something is through its opposite—just as darkness is known through light, light is known through darkness. A fundamental spiritual principle of creation itself appears to be that when one force—e.g., light—begins to emerge in the universe a counterforce, opposed to the first, arises at that same moment.

Just as shadows belong to light, these light and dark powers are interrelated, reciprocally co-arising, inseparably contained within and expressions of a single deeper unifying process. These opposites belong together precisely insofar as they oppose each other; their seeming antagonism is an expression of their essential oneness. The brightest light and darkest shadow mysteriously evoke each other, as if—behind the scenes—they are secretly related. In essence, spirit is incarnating, and it is revealing itself through the very darkness that it is making visible.

Commenting on the other—and less recognized—half of the Second Coming, Steiner chillingly said, “before the Etheric Christ can be properly understood by people, humanity must have passed through the encounter with the Beast.”[10] By “the Beast” he means the apocalyptic beast,[11] the radically evil. The Beast is the guardian of the threshold through which we must pass in order to meet the lighter, celestial and heavenly part of our nature.

As soon as I read Steiner’s prophecy I felt the truth of his words. I recognized how what Steiner was saying mapped onto—and created context for—what is happening in our current world-gone-crazy. The ever-increasing darkness that has descended like a plague onto humanity and is compelling us to race towards our own self-destruction is hard to face, let alone fathom. The evil of our time has become so gigantic that it has virtually outstripped the symbol and become autonomous, un-representable, beyond comprehension, practically unspeakable.

I also recognized the truth of what Steiner was saying based on my own inner experience. I have noticed that as I get closer to connecting with the light within myself, the forces of darkness seem to become more active and threatening. It is as if there is something in me—and in everyone, which is to say this situation isn’t personal—that desperately doesn’t want us to recognize and step into our light. This internal process is taking place within the subjectivity of countless individual human psyches, which is then reflexively being collectively acted out—in my language, “dreamed up”—en masse in, as and through the outside world. The dialectical tensions of the cosmos (the macrocosm)—the conflict between the opposites of dark and light—are mirrored both in the external collective body politic as well as within the psyche of each individual (the microcosm). It greatly serves us to recognize this.

In his prophecy, Steiner is pointing out that our encounter with the Beast is initiatory, a portal that—potentially—introduces us to the Christ figure. To quote Steiner, “Through the experience of evil it will be possible for the Christ to appear again.”[12] It is noteworthy that the opposites are appearing together: coinciding with the peak of evil is an inner development which makes it possible for the etheric Christ—who is always present and available[13]—to be seen and felt as a guiding presence that can thereby become progressively more embodied in humans, both individually and collectively as a whole species. In the extreme of one of the opposites is the seed for the birth of the other.[14]

This is a Kabbalistic idea – for example, in the Zohar, the key Kabbalistic text, it says, “There is no light except that which issues forth from darkness…and no true good except it proceed from evil.”[15] As I deepen my familiarity with Steiner’s work, it definitely dovetails with the insights of the Kabbalah, which is considered to be one of the most profound spiritual and intellectual movements in human history. Evil, according to both Steiner and the Kabbalah, though by definition diametrically opposed to the good, is—paradoxically—a catalyst for bringing the power of goodness to the fore.

Steiner felt that because Christ was destined to appear in the etheric body, “a kind of mystery of Golgotha is to be experienced anew.”[16] What Steiner means by the “mystery of Golgotha” is Christ’s crucifixion, his descent into the underworld and subsequent resurrection. As a result of the first mystery of Golgotha over two thousand years ago—what Steiner considers an act of divine grace bestowed on humanity from above—Christ has been establishing himself in the unconscious dark depths of humanity’s soul. The “Christ-impulse,” in Steiner’s words, “was to penetrate to the dark depths of man’s inner being … to the deepest part of man’s nature.”[17]

Like an iteration of a deeper fractal, this archetypal, timeless mystery now “is to be experienced anew” in a modern-day version. In no other world than the physical world can we learn the true nature of the mystery of Golgotha. To quote Steiner, “Not in vain has man been placed in the physical world; for it is here we must acquire that which leads us to an understanding of the Christ-Impulse!”[18]

Unlike the first mystery of Golgotha, however, in the culmination of this renewed mystery, humanity becomes engaged as active participants, playing a decisive role in the cosmic drama. This too is a Kabbalistic insight: humanity co-partners with the divine so as to complete the creative act of God’s Incarnation. Instead of the Incarnation being through one man, however, in our current day it is taking place through all of humanity. The modern-day coming of the Messiah is through the transformed and awakened consciousness of humanity as a whole. In a very real sense, we are the very Messiah we have been waiting for. “By a strange paradox,” according to Steiner, it is “through the forces of evil” that “mankind is led to a renewed experience of the Mystery of Golgotha.”[19]

The mystery and drama of the Christ event is now located and consummated in humanity, who become its living carrier. The events that were formulated in dogma are now brought within the range of direct psychological experience and become an essential aspect of the process of individuation. Whether we know it or not, we have become drafted and are being assimilated into a divinely-sponsored process. Not an effortful, intentional straining after imitation, this becomes an involuntary and spontaneous personal experience of the reality symbolized by the sacred legend.

The brightest, most radiant and luminous light simultaneously casts and calls forth the darkest shadows. Through this process of Christ manifesting in the etheric realm, humanity is exposed to evil in a way never before experienced, such that—in potential—we may be able to find the good and the holy in a more real and tangible way than was previously possible. Humanity’s highest virtues and potentialities are activated and called forth when confronted by evil.

It is an archetypal idea that ascending towards the light always necessitates a confrontation with and descent into the darkness; the Kabbalah calls this “a descent on behalf of the ascent.” There are certain points in time when humans—individually and/or collectively—are pulled down, submerged into darker powers, brought below a certain level against their will. This shamanic descent can be envisioned as a test for humanity, so that we may learn, through our own efforts, how to lift ourselves up. But we raise ourselves not without God’s help, however, who, paradoxically, is the very sponsor of our descent in the first place.

Seen symbolically, the process of descent—as universally exemplified in the myth of the hero—reveals that only in the region of danger can we find the alchemical “Treasure Hard to Attain.” Speaking of when someone goes through what he refers to as “the Descent into Hell,” Steiner says, “When this has been experienced, it is as though the black curtain has been rent asunder and he looks into the spiritual world.”[20]

The mystery of humanity’s higher nature is inseparable from the mystery of evil. No realization of the light would ever occur without first getting to know its opposite. Whoever wants to support the sacred must be able to protect it and we can only do so when we know the forces that oppose it. The question is not whether we believe in evil, but whether or not we are able to recognize and discern, in the actual events of life, that dimension of experience that the ancients called evil. Speaking about the evolutionary stage of modern humanity, Steiner said, “now we have to come to terms with evil.”[21] It is beyond debate that in our current age we are called to deal with evil—only those who choose to stay asleep, or are overly identified with the light (and hence, project out and dissociate from their own darkness) are blind to this.

It is of the utmost importance to recognize evil, which involves developing our capability to perceive differences, i.e., to cultivate discernment. Evil has an intense desire to remain incognito, below the radar, as its power to wreak havoc is dependent on not being recognized. If we don’t recognize evil, however, we will surely succumb to it, thereby unconsciously acting it out. We are offered a choice—to come to terms with evil or continue to avoid it (which ineluctably makes us complicit in it). Recognizing and confronting evil means getting to know its operations within ourselves without fully succumbing to it.

Recognizing the evil within us is a moment of great peril, as we don’t want to fall hopelessly into paralyzing despair at seeing the shocking depth of our own darkness. Another danger is to unconsciously identify with the evil we are seeing, thinking we are that. The key is to see these impersonal darker forces within us, recognize that we share them in common with all humanity, and then “distinguish ourselves” from them. This is to see these darker forces as paradoxically both belonging to ourselves while being other than who we are. Becoming conscious of these darker forces takes away their power (which is dependent on not being seen), liberating us from being under their thrall. It is a genuine spiritual event when we confront these darker forces in and through ourselves as if we are meeting a wholly other being.

Without being exposed to and challenged by evil we remain helpless to overcome it. The Beast is a higher-dimensional and supersensible being (beyond our five senses) that reveals itself in and through historical events in our world as well as within the inner landscapes of our psyche. A human body and soul can unwittingly (or consciously) become the vessel for acting out these powerful, darker, destructive archetypal powers in ways that further extend these forces into the world at large. In modern times the centralized, power-based state is the incorporated agency of these darker forces on a collective scale. Any of us, often with the best intentions, can unwittingly become an instrument of evil through our acting out of these darker unconscious impulses.

Encountering, recognizing and experiencing the depth of evil within ourselves helps us to develop the inner capacity to stand free of it, and in so doing, become acquainted with the part of ourselves that is beyond evil’s reach, thus enabling us to establish ourselves as free, sovereign and independent beings. Realizing this, we thereby become inoculated from being one of its carriers. Paradoxically, it is only by knowing the Beast in ourselves that we become truly human. It is to our advantage to know that our worst adversary resides in our own heart, rather than falling for the all-to-common delusion of thinking that our enemy is outside of ourselves.

Withdrawing our shadow projections from the outside world enables us to not only own and come to terms with the darkness within ourselves, but also enables us to withdraw our projections from an outward historical figure and instead discover the living Christ within. This is to recognize that Christ—symbolic of the wholeness of our true nature—has always lived in us, rather than being an external figure separate and different from ourselves. We ourselves bear Christ—the most precious treasure, “The Pearl of Great Price”—within us.

Seeing the etheric Christ necessitates the human acquisition of a newly awakened faculty of perception which enables us to recognize that a spiritual realm permeates—and is revealing itself—through the seemingly mundane physical world. The etheric Christ has an infinitude of ways, a multiplicity of guises in which it can appear. Just like a symbol in a dream, the form of the vision is custom-tailored for each soul, dependent on our state of evolution. As we each see the etheric Christ in the unique form appropriate to our soul, we rise up, lift ourselves—grow and ascend upwards, evolutionarily speaking—towards Christ in his etheric body. To quote Steiner, “those who raise themselves—with Full ego-consciousness—to the etheric vision of Christ in His etheric body, will be ‘God-filled’ or blessed. For this, however, the materialistic mind must be thoroughly overcome.”[22]

Speaking of the power of the etheric Christ, Steiner said, “When this power has permeated the soul, it drives away the soul’s darkness.”[23] As we stabilize our vision of the etheric Christ, we recognize that, as if looking in a mirror, we are seeing our own reflection. Christ himself (in his etheric form) says in the apocryphal Acts of John, “A mirror am I to thee that perceivest me … behold thyself in me who speak.”[24] On the one hand this mirror reflects back our own temporal, limited and subjective consciousness, while on the other hand simultaneously reflecting back the transcendental aspect of ourselves that is already whole, healed and awake. These co-joined reflections invite us to cultivate the ability to differentiate them, and in so doing effects the requisite transformation of consciousness that feeds our individuation.

In these encounters with the etheric Christ, we are not witness to an external, material, objective event that comes from outside of ourselves, but our soul is itself the medium in which the engagement takes place. In its subjective experience of the etheric Christ, it is its own image of itself that the soul rediscovers and meets in its act of reflection. The soul is itself reflected through and reciprocally affected by the vision of the etheric Christ. Inseparable parts of one quantum system, the etheric Christ’s radiance doesn’t shine separate from humanity; its luminous clarity is our own. Humanity invariably becomes transformed when it encounters the etheric Christ, due to our consciousness becoming aware of an essential aspect of itself that was heretofore hidden and relegated to the unconscious.

The part of Steiner that was envisioning the operations of the etheric Christ was the etheric Christ himself seeing through Steiner’s eyes; the same is true for us. When we see the etheric Christ, we begin to assimilate and become the thing we are seeing. In our apperception, the etheric Christ inside of us recognizes itself, which enables us to step into who we’ve always been. Humanity is the vessel through which the etheric Christ—the spirit of Christ—takes on human form and incarnates itself.

We find ourselves playing a key role in a cosmic drama. We are not just passive witnesses, but active participants in a momentous, world-transforming spiritual event. In Steiner’s words, “The human being is not a mere spectator that stands over against the world … he is the active co-creator of the world process.”[25] Steiner’s statement is completely in alignment with the realizations of quantum physics, which points out that we are participating—whether we know it or not—in the creation of our experience of both the world and ourselves. What Steiner is describing in terms of the incarnation of the etheric Christ and the emergence of the apocalyptic Beast is in some mysterious way related to—and reflecting—the current stage of our collective psycho-spiritual development.

The worst illness is the one which goes unrecognized, as it therefore cannot be treated. According to Steiner, awareness of the covert operations of these darker forces is the only means whereby their aims may be counteracted.[26] The etheric Christ’s light can help us to break through our massive inner resistance against seeing to what an overwhelming extent the forces of illness and death have insinuated themselves into our organism and corrupted our soul. The same light that kindles consciousness—i.e., the etheric Christ—also illuminates the deadening and rigidifying forces in humanity’s being. If we can consciously experience the powerlessness that has become allied with the deadening forces in our soul, this sense of our powerlessness—like hitting bottom—can lead us to an experience of the etheric Christ, which itself is the revivifying light of awareness which enabled us to become aware of our powerlessness in the first place. Consciously seeing the withered soul of our time—intellectualized and materialized to death—is a crucial step which initiates the process of resuscitating—and resurrecting—the soul, bringing it to life again.

As if pouring the very essence of his being into the existential abyss, Christ concealed his light by incorporating himself in humanity’s deadened life forces, as if the higher self clothed itself in the evil qualities of humanity. To quote a student of Steiner, Jesaiah Ben-Aharon, “The Christ is seen through the metamorphosed forces of death, and is experienced through the mystery of man’s evil.”[27] The life-enhancing etheric Christ is made out of the devitalizing forces of death that have seemingly imprisoned and obscured the eternal Christ within us. Christ’s “resurrection body” is created and forged through the descent into hell. The very fabric of the darkness are the celestial threads out of which the etheric Christ is woven.[28]

Through his descent into the depths of the underworld, Christ merged and united himself completely with the core of humanity’s evil—becoming one with it—thereby initiating an alchemical process of transformation deep within the universe itself. Steiner’s description of the incarnation of the etheric Christ implies a progressive transmutation of the underlying etheric substructure of our world, i.e., a change in the energetic fabric of space-time itself.[29] In dying livinglyinto the abyss, Christ freely offered his life-giving heart to darkness’s infinite void. The result of Christ’s sacrifice is that his eternal being germinates and grows for humanity from within the core of all evil.

Through his descent into the hell realms, a mutual interpenetration between the lower and higher selves of the universe has taken place. Light has taken on darkness, which has a double meaning: to encounter darkness, as well as to become it. Light has transformed itself into darkness so as to know and illumine the darkness from the inside as well as to reveal itself. Evil—which on one level is obscuring the light—has encoded within itself its very opposite, i.e., it has become the revelation of the very light it seems to be concealing.[30]If we don’t recognize this, however, the darkness will continue to manifest destructively and eventually destroy us.

Being the most problematic element in the life of our species, evil demands our deepest sobriety and most earnest reflection. It behooves us to become conscious of the ways we are unknowingly colluding with darker forces. The etheric Christ illumines not only the existence of evil as a reality in the depth of the soul, but its light also reflects our complicity in this evil to the degree that we turn a blind-eye towards it. Individual self-reflection, which returns us to the deeper, darker ground of our light-filled nature, is the beginning of the cure for the blindness which reigns today. We tend to think of illumination as “seeing the light,” but seeing the darkness is also an important form of illumination.

We fervently avoid investigating whether God might have placed some unrecognized purpose in evil that is crucial for us to know. If we become conscious of the evil within us, in our expansion of consciousness, that evil is promoting our spiritual development. We have then, through our realization, alchemically transmuted evil into a catalyst for our evolution. To quote Steiner, “The task of evil is to promote the ascent of the human being.”[31] Once we realize our collusion with evil—making an unconscious part of us conscious, evil—with our co-operation—has fulfilled its mission of promoting our ascent.

This is once again in alignment with the Kabbalah, which conceives of evil as an essential component of the deity, woven into the very fabric of creation. Evil, according to both Steiner and the Kabbalah, co-emerges with the possibility of humanity’s freedom, as if God could not create true freedom for humanity without providing a choice for evil. To quote Steiner, “In order for human beings to attain to full use of their powers of freedom, it is absolutely necessary that they descend to the low levels in their world conception as well as in their life.”[32] From both Steiner’s and the Kabbalistic point of view, evil is created by and for freedom, and it is only through the conscious exercise of freedom of choice—which evil itself challenges us to develop—by which it can be overcome. To quote Steiner, “This is the great question of the dividing of the ways: either to go down or to go up.”[33]

The question naturally arises: if, as Steiner and the Kabbalah profess, freedom is actualized only through the existence of evil, is evil an expression of a higher intelligence, an aspect of the divine plan designed to bring about a higher form of good that couldn’t be actualized without its existence? In other words, is evil against God, or on a deeper level, serving God?

Answering this question involves a new way of translating our experience to ourselves. This way of seeing can only be attained if we are not stuck in a fixed, polarized viewpoint, caught in binary, dualistic thinking. The price of admission to this new perspective is being open to how the opposites—e.g., good and evil—are not opposed to each other in the way that we’ve been imagining if we’ve been imagining them as being separate. Seeing this involves a deeper integration within ourselves in which we are able to carry—and hold together without splitting—the seeming opposites in a new way. This expansion of our consciousness not only supports the incarnation of the etheric Christ, it is the incarnation itself.

How are we to live in such close proximity to evil? Steiner’s prophecy—expressed in the language of Christianity—is suggesting that a complete spiritual renewal is urgently needed. And as Steiner indicates, no spiritual transformation is possible without coming to terms with the Beast, i.e., with the inescapable factor of evil encountered both within ourselves and in the outside world. No old formulas or techniques can fit the bill; the answer of how to deal with such darkness is only to be found in the depths of the individual human heart.

The main aim of the Beast is to close, harden and seal the human heart with its negative energies. There is no greater protection against the Beast—as well as no better way to invite the approach of the etheric Christ—than to assiduously strive to cultivate a good heart over-flowingly filled with compassion. Genuine compassion is unconditioned; by its nature it is meant to be shared with all beings throughout the whole universe, most especially with the Beast within ourselves. Compassion is the only thing in the world that can vanquish the seemingly infinite black hole of evil, as compassion—due to its boundless nature—has no limits, which means the more we give compassion, the more we have to give. The etheric Christ is all about compassion, which is its true name.

~

A pioneer in the field of spiritual emergence, Paul Levy is a wounded healer in private practice, assisting others who are also awakening to the dreamlike nature of reality. He is the author of The Quantum Revelation: A Radical Synthesis of Science and Spirituality (SelectBooks, May 2018), Awakened by Darkness: When Evil Becomes Your Father (Awaken in the Dream Publishing, 2015), Dispelling Wetiko: Breaking the Curse of Evil (North Atlantic Books, 2013) and The Madness of George W. Bush: A Reflection of Our Collective Psychosis (Authorhouse, 2006). He is the founder of the “Awakening in the Dream Community” in Portland, Oregon. An artist, he is deeply steeped in the work of C. G. Jung, and has been a Tibetan Buddhist practitioner for over thirty years. He was the coordinator for the Portland PadmaSambhava Buddhist Center for over twenty years. Please visit Paul’s website www.awakeninthedream.com. You can contact Paul at paul@awakeninthedream.com; he looks forward to your reflections.

[1] Steiner lived from 1861–1925. This prediction was made in 1924, but wasn’t made known till 1991. The word clairvoyantliterally means “clear-seeing;” a clairvoyant is a “clear-seer.”

[2] The word “etheric” derives from the word “ether,” which is a word that was once widely used in physics (during Steiner’s lifetime) to refer to the medium of space itself. The word etheric thus implied a presence co-extensive with space and is thus something that completely pervades and is fully present in and as the material forms of the world. There is nowhere where space is not, which is to say it is omnipresent and everywhere. As if a higher-dimensional substance-less substance, space is the one element in which all of the other elements in the universe exist and take on their being. The ether’s presence was therefore conceived of as not being explicit like that of material forms, but like space is more hidden and implicit, in that it doesn’t assume any specific form but instead provides the underlying basis and nonphysical context for physical form to arise in the first place.

[3] Other noteworthy examples of the manifestation of the etheric Christ are Paul’s encounter with Christ in his etheric form on the way to Damascus, and the Gnostic document Pistis Sophia (in which Christ appeared to some of his disciples, including Mary Magdalene, in his transfigured, resurrection body, giving them teachings for eleven years).

[4] Rudolf Steiner. Christ at the time of the Mystery of Golgotha and Christ in the twentieth century. 2 May 1913, London. GA 152. In: Occult Science & Occult Development. Rudolf Steiner Press, London 1966.

[5] Rudolf Steiner, The Reappearance of Christ in the Etheric, 43.

[6] Ibid, 91.

[7] Rudolf Steiner. Christ at the time of the Mystery of Golgotha and Christ in the twentieth century. 2 May 1913, London. GA 152. In: Occult Science & Occult Development.

[8] Lecture at Stuttgart on 6 March 1910. In: The Reappearance of Christ in the Etheric.

[9] Rudolf Steiner, The Reappearance of Christ in the Etheric, 45.

[10] From a lecture to the priests of the Christian Community, September 1924, cited by Harold Giersch: Rudolf Steiner uber die Wiederkunft Christi [Concerning the reappearance of Christ], Dornach 1991, p. 110.

[11] Steiner said that an incarnation of the Beast will first arise in 1933, which is when Hitler came to power.

[12] Rudolf Steiner: From Symptom to Reality in Modern History, lecture 4, Rudolf Steiner Press 1976, p. 112.

[13] Speaking about what Paul saw during his Damascus Experience (where Paul had a conversion experience after seeing the etheric Christ), Steiner said, “that Christ is in the Earth-atmosphere and that he is always there!” Rudolf Steiner, The Christ Impulse and Development of the Ego-Consciousness (London: Anthroposophical Publishing Co., 1926, reprinted by Kessinger), 48. In this statement Steiner is making an equivalence between the etheric Christ and the element space.

[14] The yin/yang symbol represents this pictorially.

[15] Zohar II, 184a; Sperling and Simon, The Zohar, Vol. IV, p. 125.

[16] Rudolf Steiner: From Symptom to Reality in Modern History, lecture 4, Rudolf Steiner Press 1976, p. 112.

[17] Steiner, The Christ Impulse and Development of the Ego-Consciousness, 42.

[18] Ibid., 50.

[19] Rudolf Steiner: From Symptom to Reality in Modern History, lecture 4, Rudolf Steiner Press 1976, p. 112.

[20] Quoted from The Essential Steiner, Robert A. McDermott, ed. (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1984), 264.

[21] GA (which stands for Gesamtausgabe, the collected edition of Rudolf Steiner’s work in the original German), 178, 18/11/17.

[22] Steiner, The Christ Impulse and Development of the Ego-Consciousness, 48.

[23] GA 118, 27/01/10.

[24] M. R. James, ed., The New Testament Apocrypha(Berkeley, CA: Apocryphile Press, 2004), 253-254.

[25] From Steiner’s doctoral dissertation Truth and Science(1892).

[26] GA 178, 13/11/17.

[27] Jesaiah Ben-Aharon, The New Experience of the Supersensible (East Sussex, UK: Temple Lodge Publishing, 2007), 46.

[28] The darkening death forces within us continually persecutes the Christ in us, continually creating opaqueness, deadening and ossification. This process is symbolized in Paul’s Damascus experience when he encountered the etheric Christ and had a conversion experience (symbolized by changing his name from Saul to Paul). To quote from Acts 8:4, “Saul, Saul, why persecutest me?”

[29] Steiner’s notion of the coming of the etheric Christ has striking similarities to V. I. Vernadsky and Teilhard de Chadin’s concept of the noosphere (the mental-etheric envelope that embraces and pervades the living biosphere of our planet, the growth of which supports and catalyzes the evolution of human consciousness).

[30] In medical terminology, evil can be conceived of as being a “cosmic carcinoma.” If seen as a disease, encoded within evil is its own medicine (what I call “participatory medicine,” in that, in true quantum style, how the seeming pathology actually manifests depends upon how we engage with it). Containing not just its own cure, this malevolent disease actually bears hidden within it life-enhancing gifts beyond measure. How this disease manifests—in its cursed or blessed aspect—depends upon if we recognize what it is revealing to us.

[31] GA 95, 29/08/06.

[32] GA 204, 02/04/21.

[33] Steiner, The Christ Impulse and Development of the Ego-Consciousness, 63.