By Pattern Theory

Source: Modern Mythology

Cyberpunk broke science fiction. Creeping in alongside the commercialization of the internet, it extrapolated the corruption and dysfunction of its present into a brutal and interconnected future that remained just a heartbeat away. Cyberpunk had an attitude that refused to be tamed, dressed in a style without comparison. Its resurgence shows that little has changed since its inception, and that’s left cyberpunk incapable of discussing our future.

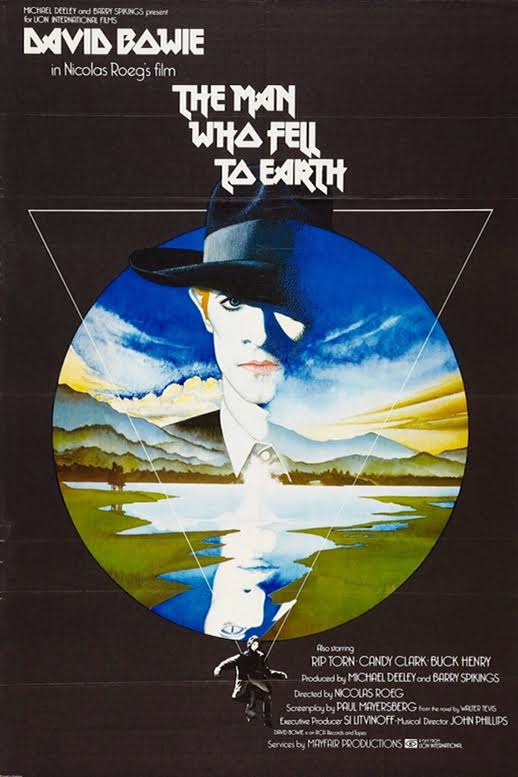

Ghost in the Shell got the live-action treatment in 2017, a problematic remakeof the 1995 adaptation. Some praised its art direction for increasing the visual fidelity of retrofuture anime cityscapes, but the general consensus was that the story failed to apply care and consideration towards human brains and synthetic bodies like Mamoru Oshii had more than two decades before. A few months later came Blade Runner 2049, a sequel to the cyberpunk classic. Critics and fans praised it for high production values, sincere artistic effort, and meticulous direction. Yet something had gone wrong. Director Denis Villeneuve couldn’t shake the feeling that he was making a period movie, not one about the future.

Enough has changed since the 1980s that cyberpunk needs reinvention. New aesthetics. An expanded vocabulary. Code 46 managed this years ago. It rejects a fetish for all things Japanese and embraces China’s economic dominance. Conversations being in English and are soon peppered with Mandarin and Spanish. Life takes place at night to avoid dangerous, unfiltered sunlight. Corporations guide government decisions. Genetics determine freedom of movement and interaction. Climate refugees beg to leave their freeway pastures for the safety of cities.

Code 46 is cyberpunk as seen from 2003, a logical future that is now also outdated.

If Blade Runner established the look, Neuromancer defined cyberpunk’s voice. William Gibson’s debut novel was ahead of the curve by acknowledging the personal computer as a disruptive force when the Cold War was at its most threatening. “Lowlife and high tech” meant the Magnetic Dog Sisters headlining some creep joint across the street from a capsule hotel where console cowboys rip off zaibatsus with their Ono Sendai Cyberdeck. But Gibson’s view of the future would be incomplete without an absolute distrust of Reaganism:

“If I were to put together a truly essential thank-you list for the people who most made it possible for me to write my first six novels, I’d have to owe as much to Ronald Reagan as to Bill Gates or Lou Reed. Reagan’s presidency put the grit in my dystopia. His presidency was the fresh kitty litter I spread for utterly crucial traction on the icey driveway of uncharted futurity. His smile was the nightmare in my back pocket.” — William Gibson

“Fragments of a Hologram Rose” to Mona Lisa Overdrive is a decade of creative labor that was “tired of America-as-the-future, the world as a white monoculture.” The Sprawl is a cyberpunk trilogy where military superpowers failed and technology gave Japan leadership of the global village. Then Gibson wrote Virtual Light and readers witnessed extreme inequality shove the middle class into the gig economy as corporations schemed to profit off natural disasters with proprietary technology.

Gibson knew the sci-fi he didn’t care for would absorb cyberpunk and tame its “dissident influence”, so the genre could remain unchanged. “Punk” is the go-to suffix for emerging subgenres that want to appear subversive while posing a threat to nothing and no one. It’s how “hopepunk” becomes a thing. But to appreciate cyberpunk’s assimilation, look at how it’s presented sincerely.

CD Projekt Red (CDPR), known for the Witcher game series, has spent six years developing what’s arguably the most anticipated video game of the moment, Cyberpunk 2077. Like Gibson, Mike Pondsmith, creator the original “pen-n-paper” RPG, and collaborator on this adaptation of his work, has had his writing absorbed by mainstream sci-fi. CDPR could survive on that 31-year legacy, but they insist they’re taking their time with Cyberpunk 2077 to craft an experience with a distinct political identity that somehow allows players to remain apolitical. In a way this is reflective of CDPR’s reputation as a quality-driven business that’s pro-consumer, but has driven talent away by demanding they work excessive hours and promoting a hostile attitude towards unions. This crunch culture is a problem across the industry.

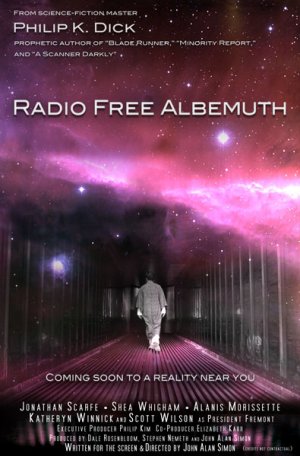

We’ll soon see how Cyberpunk 2077 developed. What we can infer from its design choices, like giving protagonist V a high-collar jacket seen on the cover of the 2nd edition game book from 1990, is that Cybperpunk 2077 will be familiar. Altered Carbon and Ready Player One share this problem. Altered Carbon is so derivative of first-wave cyberpunk it’s easy to forget its based on a novel from 2002. Ready Player One at least has the courtesy to be shameless in its love of pop culture, proud to proclaim that nothing is more celebrated today than our participation in media franchises without ever considering how that might be a problem.

What’s being suggested, intentionally or not, is that contemporary reality has avoided the machinations of the powerful at a time when technology is wondrous, amusing, and prolific. If only we were so lucky.

238 cities spent more than a year lobbying Amazon, one of two $1 trillion corporations in existence, for privilege of hosting their new office. In November it was announced that Amazon would expand to Crystal City, Virginia and Long Island City, Queens. Plenty of New Yorkers are incensedthat the world’s largest online marketplace will get $3 billion in subsidies, tax breaks, and grants to further disrupt a housing market that takes more from them than any city should allow. Some Amazon employees were so excited to relocate they made down payments on their new homes before the decision went public, telling real estate developers to get this corner of New York readyfor a few thousand transplants. But what of the people already there?

Long Island City is home to the Queensbridge Houses, the largest housing project in the US. Built in 1939, these two buildings are home to more then 6,000 people with an average income of $16,000. That’s far below the $54,000 for Queens residents overall. But neither group is anywhere near the average salary for the 25,000 employees Amazon will bring with them, which will exceed $150,000. How many of those positions will be filled by locals? How many will come from Queensbridge?

Over 800 languages are spoken in Queens, making it the most linguistically diverse place in the world. Those diverse speakers spend over 30% of their income on rent. They risk being priced out of their neighborhoods. Some will be forced out of the city. Has Governor Cuomo considered the threat this deal poses to people’s homes? Has Mayor de Blasio prepared for the inevitable drift to other boroughs once property values spike? Looking at Seattle and San Francisco, there’s no reason to expect local governments to be proactive. So New Yorkers have taken up the fight on their own.

Amazon boss Jeff Bezos toyed with these politicians. He floated the idea that any city could become the next Silicon Valley and they believed him. They begged for his recognition, handed over citizen data, and took part in the $100 billion ritual of subsidizing tech companies.

It was all for nothing. Crystal City is a 20-minute drive from Bezos’ house in Washington DC, where Amazon continues to increase its spending on lobbyists. That’ll seem like a long commute compared to the helicopter ride from Long Island City, the helipad for which is subsidized by the city, to Manhattan, the financial and advertising capital of the world, where Bezos owns four more houses.

The auction for Bezos’ favor was a farce. New York and Virginia give him regular access to people with decision-making power, invaluable data, and institutions that are are sure to expand his empire. These cities were always the only serious options.

Amazon’s plans read like the start of a corporate republic, a cyberpunk trope inspired by company towns. Employers were landlords, retailers, and even moral authorities to workforces too in debt to quit. Many had law enforcement and militias to call on in addition to the private security companies they hired to break labor strikes, investigate attempts at unionization, and maintain a sense of order that resulted in massacres like Ludlow, Colorado.

Amazon is known for labor abuses, monitoring, and tracking speed and efficiency in warehouses without bathroom breaks, where employees have collapsed from heat exhaustion. They sell unregulated facial recognition services to police departments, knowing it misidentifies subjects because of inherent design bias. Companies with a history of privacy abuses have unfettered access to their security devices. They control about half of all e-commerce in the US and, as Gizmodo’s Kashmir Hill found out, it is impossible to live our lives without encountering Amazon Web Services.

It doesn’t take a creative mind to imagine similar exposition being attributed to corporate villains like Cayman Global or Tai Yong Medical.

Rewarding corporations for their bad behavior is just one way the world resembles a fictive dystopia. We also have to face rapid ecological and institutional decay that fractionally adjusts our confidence in stability, feeding a persistent situational anxiety. That should make for broader and bolder conversations about the future, and a few artists have managed to do that.

Keiichi Matsuda is the designer and director behind Hyper-Reality, a short film that portrays augmented reality as a fever dream that influences consumption, and shows how freeing and frightening it is to be cut off from that network. Matsuda’s short film got him an invitation to the World Economic Forum in Davos to “speak truth to power.” What Matsuda witnessed were executives and billionaires pledging responsibility with t-shirts and sustainability, while simultaneously destroying the environment, as an audience of their peers and the press nodded and applauded “this brazen hypocrisy.” So Matsuda took a stanchion to his own installation.

Independence means Matsuda gets to decide how to talk about technology and capitalism, and how to separate his art and business. It also means smaller audiences and fewer productions.

Sam Esmail used a more visible platform to “bring cyberpunk to TV” with Mr. Robot. Like Gibson’s Pattern Recognition, it’s cyberpunk retooled for the present — post-cyberpunk. Esmail never hesitates to place our villains in Mr. Robot. Enron is an influence on logo designs and tactics of evil corps. Google, Verizon, and Facebook are called out for their complicity with the federal government in exposing customer data. AT&T’s Long Lines building, an NSA listening post since the 1970s, plays the role of a corporate data hub that reaches across the county. Even filming locations serve as commentary.

An anti-capitalist slant runs through Mr. Robot, exposing the American dream as a lie and our concept of meritocracy as a tool to protect the oligarchy, presenting hackers as in direct contact with a world of self-isolation and exploitation, those who dare to hope for a future affected by people rather than commerce. And Esmail somehow manages this without interference from NBC.

Blade Runner will get more life as an anime. Cowboy Bebop is joining Battle Angel Alita in live action. Altered Carbon is in the process of slipping into a new sleeve. There’s no shortage of revivals, remakes, and rehashing of cyberpunk’s past on the way. They’ll get bigger audiences than a short film about submitting to algorithms. More sites will discuss their pros and cons than a mobile tie-in that name-drops Peter Kropotkin and Maria Nikiforova. But in being descriptive and prescriptive, moving to the future and looking for sure footing in the accelerated present, Matsuda’s and Esmail’s work reminds us that cyberpunk needs to be more than just repeating what’s already been said about yuppies, Billy Idol, and the Apple IIc.

We live at a time where 3D printing is so accessible refugees can obtain prosthesis as part of basic aid. People forced to migrate because of an iceless arctic will rely on that assistance. Or we could lower temperatures and slow climate change by spraying the atmosphere with sulfate, an option that might disrupt advertising in low-orbit. Social credit systems are bringing oppressive governments together. Going cashless is altering our expectations of others. Young people earn so little they’re leveraging nude selfies to extend meager lines of credit. Productivity and constant notifications are enough to drive some into a locked room, away from anything with an internet connection. Deepfakes deny women privacy, compromise their identity, and obliterate any sense of safety in exchange for porn. Online communities are refining that same technology, making false video convincing, threatening our sense of reality. Researchers can keep our memories alive in chat bots distilled from social media, but the rich will outlive us all by transfusing bags of teenage blood purchased through PayPal.

In a world that increasingly feels like science fiction it’s important to remind ourselves that writing about the future is writing about the present. Artists worthy of an audience should be unable to look at the embarrassment of inspiration around them and refuse the chance to say something new.