By John & Nisha Whitehead

Source: The Rutherford Institute

“Crush! Kill! Destroy!”—The Robot, Lost in Space

The purpose of a good government is to protect the lives and liberties of its people.

Unfortunately, we have gone so far in the opposite direction from the ideals of a good government that it’s hard to see how this trainwreck can be redeemed.

It gets worse by the day.

For instance, despite an outcry by civil liberties groups and concerned citizens alike, in an 8-3 vote on Nov. 29, 2022, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors approved a proposal to allow police to arm robots with deadly weapons for use in emergency situations.

This is how the slippery slope begins.

According to the San Francisco Police Department’s draft policy, “Robots will only be used as a deadly force option when risk of loss of life to members of the public or officers is imminent and outweighs any other force option available to SFPD.”

Yet as investigative journalist Sam Biddle points out, this is “what nearly every security agency says when it asks the public to trust it with an alarming new power: We’ll only use it in emergencies—but we get to decide what’s an emergency.”

A last-minute amendment to the SFPD policy limits the decision-making authority for deploying robots as a deadly force option to high-ranking officers, and only after using alternative force or de-escalation tactics, or concluding they would not be able to subdue the suspect through those alternative means.

In other words, police now have the power to kill with immunity using remote-controlled robots.

These robots, often acquired by local police departments through federal grants and military surplus programs, signal a tipping point in the final shift from a Mayberry style of community policing to a technologically-driven version of law enforcement dominated by artificial intelligence, surveillance, and militarization.

It’s only a matter of time before these killer robots intended for use as a last resort become as common as SWAT teams.

Frequently justified as vital tools necessary to combat terrorism and deal with rare but extremely dangerous criminal situations, such as those involving hostages, SWAT teams—which first appeared on the scene in California in the 1960s—have now become intrinsic parts of local law enforcement operations, thanks in large part to substantial federal assistance and the Pentagon’s military surplus recycling program, which allows the transfer of military equipment, weapons and training to local police for free or at sharp discounts.

Consider this: In 1980, there were roughly 3,000 SWAT team-style raids in the U.S. By 2014, that number had grown to more than 80,000 SWAT team raids per year.

Given the widespread use of these SWAT teams and the eagerness with which police agencies have embraced them, it’s likely those raids number upwards of 120,000 by now.

There are few communities without a SWAT team today.

No longer reserved exclusively for deadly situations, SWAT teams are now increasingly deployed for relatively routine police matters, with some SWAT teams being sent out as much as five times a day. In the state of Maryland alone, 92 percent of 8200 SWAT missions were used to execute search or arrest warrants.

For example, police in both Baltimore and Dallas have used SWAT teams to bust up poker games. A Connecticut SWAT team swarmed a bar suspected of serving alcohol to underage individuals. In Arizona, a SWAT team was used to break up an alleged cockfighting ring. An Atlanta SWAT team raided a music studio, allegedly out of a concern that it might have been involved in illegal music piracy.

A Minnesota SWAT team raided the wrong house in the middle of the night, handcuffed the three young children, held the mother on the floor at gunpoint, shot the family dog, and then “forced the handcuffed children to sit next to the carcass of their dead pet and bloody pet for more than an hour” while they searched the home.

A California SWAT team drove an armored Lenco Bearcat into Roger Serrato’s yard, surrounded his home with paramilitary troops wearing face masks, threw a fire-starting flashbang grenade into the house, then when Serrato appeared at a window, unarmed and wearing only his shorts, held him at bay with rifles. Serrato died of asphyxiation from being trapped in the flame-filled house. Incredibly, the father of four had done nothing wrong. The SWAT team had misidentified him as someone involved in a shooting.

These incidents are just the tip of the iceberg.

Nationwide, SWAT teams have been employed to address an astonishingly trivial array of nonviolent criminal activity or mere community nuisances: angry dogs, domestic disputes, improper paperwork filed by an orchid farmer, and misdemeanor marijuana possession, to give a brief sampling.

If these raids are becoming increasingly common and widespread, you can chalk it up to the “make-work” philosophy, by which police justify the acquisition of sophisticated military equipment and weapons and then rationalize their frequent use.

Mind you, SWAT teams originated as specialized units that were supposed to be dedicated to defusing extremely sensitive, dangerous situations (that language is almost identical to the language being used to rationalize adding armed robots to local police agencies). They were never meant to be used for routine police work such as serving a warrant.

As the role of paramilitary forces has expanded, however, to include involvement in nondescript police work targeting nonviolent suspects, the mere presence of SWAT units has actually injected a level of danger and violence into police-citizen interactions that was not present as long as these interactions were handled by traditional civilian officers.

Indeed, a study by Princeton University concludes that militarizing police and SWAT teams “provide no detectable benefits in terms of officer safety or violent crime reduction.” The study, the first systematic analysis on the use and consequences of militarized force, reveals that “police militarization neither reduces rates of violent crime nor changes the number of officers assaulted or killed.”

In other words, warrior cops aren’t making us or themselves any safer.

Americans are now eight times more likely to die in a police confrontation than they are to be killed by a terrorist.

The problem, as one reporter rightly concluded, is “not that life has gotten that much more dangerous, it’s that authorities have chosen to respond to even innocent situations as if they were in a warzone.”

Now add killer robots into that scenario.

How long before these armed, militarized robots, authorized to use lethal force against American citizens, become as commonplace as SWAT teams and just as deadly?

Likewise, how long before mistakes are made, technology gets hacked or goes haywire, robots are deployed based on false or erroneous information, and innocent individuals get killed in the line of fire?

And who will shoulder the blame and the liability for rogue killer robots? Given the government’s track record when it comes to sidestepping accountability for official misconduct through the use of qualified immunity, it’s completely feasible that they’d get a free pass here, too.

In the absence of any federal regulations or guidelines to protect Americans against what could eventually become autonomous robotic SWAT teams equipped with artificial intelligence, surveillance and lethal weapons, “we the people” are left defenseless.

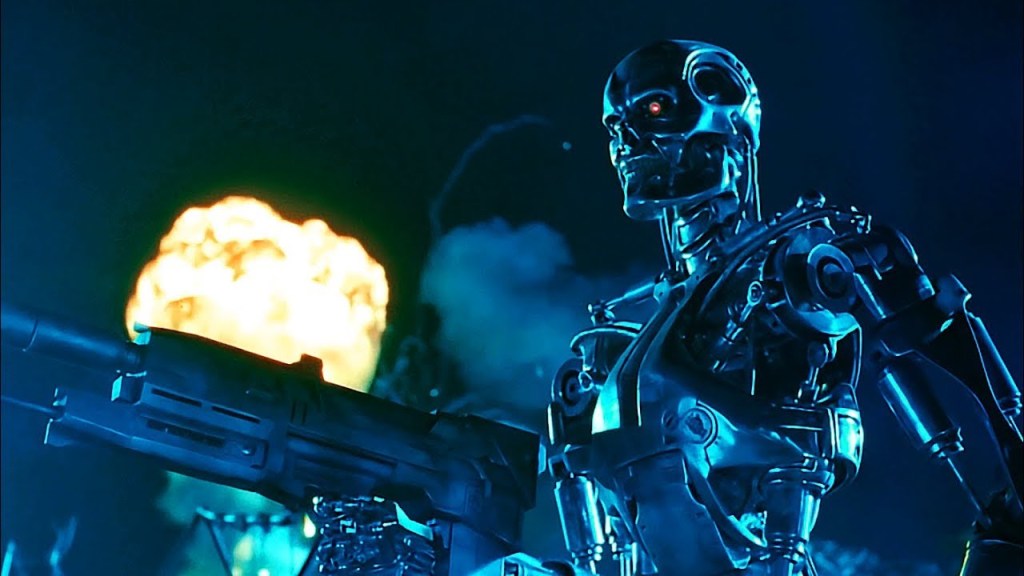

We’re gaining ground fast on the kind of autonomous, robotic assassins that Terminator envisioned would be deployed by 2029.

If these killer robots follow the same trajectory as militarized weapons, which, having been deployed to local police agencies as part of the Pentagon’s 1033 recycling program, are turning America into a battlefield, it’s just a matter of time before they become the first line of defense in interactions between police and members of the public.

Some within the robotics industry have warned against weaponizing general-purpose robots, which could be used “to invade civil rights or to threaten, harm, or intimidate others.”

Yet it may already be too late for that.

As Sam Biddle writes for The Intercept, “As with any high-tech toy, the temptation to use advanced technology may surpass whatever institutional guardrails the police have in place.”

There are thousands of police robots across the country, and those numbers are growing exponentially. It won’t take much in the way of weaponry and programming to convert these robots to killer robots, and it’s coming.

The first time police used a robot as a lethal weapon was in 2016, when it was deployed with an explosive device to kill a sniper who had shot and killed five police officers.

This scenario has been repeatedly trotted out by police forces eager to add killer robots to their arsenal of deadly weapons. Yet as Paul Scharre, author of Army Of None: Autonomous Weapons And The Future Of War, recognizes, presenting a scenario in which the only two options are to use a robot for deadly force or put law enforcement officers at risk sets up a false choice that rules out any consideration of non-lethal options.

As Biddle concludes:

“Once a technology is feasible and permitted, it tends to linger. Just as drones, mine-proof trucks, and Stingray devices drifted from Middle Eastern battlefields to American towns, critics of … police’s claims that lethal robots would only be used in one-in-a-million public emergencies isn’t borne out by history. The recent past is littered with instances of technologies originally intended for warfare mustered instead against, say, constitutionally protected speech, as happened frequently during the George Floyd protests.”

This gradual dismantling of cultural, legal and political resistance to what was once considered unthinkable is what Liz O’Sullivan, a member of the International Committee for Robot Arms Control, refers to as “a well-executed playbook to normalize militarization.”

It’s the boiling frog analogy all over again, and yet there’s more at play than just militarization or suppressing dissent.

There’s a philosophical underpinning to this debate over killer robots that we can’t afford to overlook, and that is the government’s expansion of its power to kill the citizenry.

Although the government was established to protect the inalienable rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness of the American people, the Deep State has been working hard to strip us of any claims to life and liberty, while trying to persuade us that happiness can be found in vapid pursuits, entertainment spectacles and political circuses.

Having claimed the power to kill through the use of militarized police who shoot first and ask questions later, SWAT team raids, no-knock raids, capital punishment, targeted drone attacks, grisly secret experiments on prisoners and unsuspecting communities, weapons of mass destruction, endless wars, etc., the government has come to view “we the people” as collateral damage in its pursuit of absolute power.

As I make clear in my book Battlefield America: The War on the American People and in its fictional counterpart The Erik Blair Diaries, we are at a dangerous crossroads.

Not only are our lives in danger. Our very humanity is at stake.