(Editor’s note: In commemoration of director David Cronenberg’s 75th birthday we present this compelling and socially relevant analysis of his filmography.)

By Michael Grasso

Source: We Are the Mutants

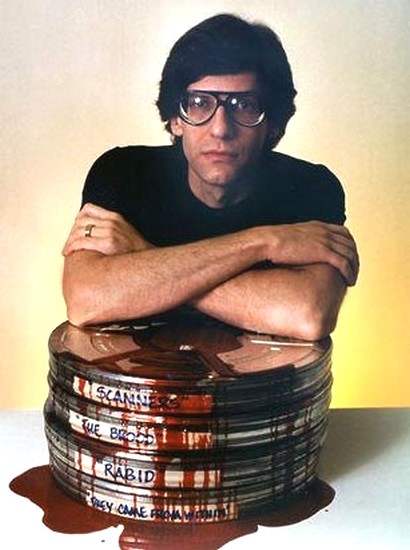

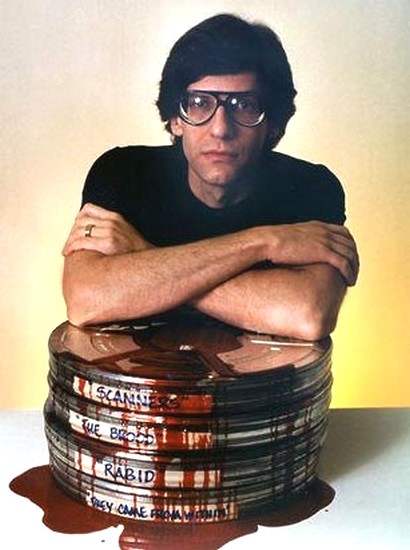

The cinematic corpus of David Cronenberg is probably best known for its expertly uncanny use of body horror, but looming almost as large in the writer-director’s various universes is the presence of faceless, all-powerful organizations. Like his rough contemporary Thomas Pynchon and the conspiracies that litter Pynchon’s early works—V. (1963), The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), and Gravity’s Rainbow (1973)—Cronenberg’s shadowy organizations offer fodder for paranoid conspiracy. These conspiracies operate under the cloak of beneficent academic institutes and, in his later work, corporations. The transition from institutes to corporations occurred during Cronenberg’s late ’70s and early ’80s output, specifically the trio of films The Brood (1979), Scanners (1981), and Videodrome (1983).

It is no coincidence that, at this particular time, international finance and prevailing political winds helped put the corporation in society’s driver’s seat. In Adam Curtis’s recent documentary film HyperNormalisation (2016), he notes how the default of the city of New York in 1975 opened the door for private investment and the finance industry to get their hands on municipal governance on a large scale for the first time, and how this creaked open the door for the Thatcher-Reagan privatization wave in the ’80s. These last few “hinge” years of the 1970s offered the last chance for a real alternative to the coming neoliberal revolution. Soon, all alternatives for governance in the name of the public good were destroyed. Corporatism tightened its grip on the Western polity.

Cronenberg’s early eerie organizations—the “Canadian Academy of Erotic Enquiry” from Stereo (1969) and the panoply of gruesome academic and cosmetic conspiracies in his Crimes of the Future (1970)—eventually yielded to corporations like Scanners‘ ConSec and Videodrome‘s Spectacular Optical. In these early works, Cronenberg’s mysterious organizations are headed by visionary (mad) geniuses. In 1975’s Shivers, experiments by a lone mad scientist infect an entire apartment building with parasites, which awaken dark impulses in the building’s residents and spread themselves through sexual violence. But as the decade went on, Cronenberg slowly backed away from utilizing the character of a singular scientific genius harboring a twisted vision of the future. Now, organizations sought to pull the strings from the shadows. The key transitional work in this chronology is the sometimes-underlooked The Brood from 1979.

In the film, Oliver Reed plays esteemed psychologist Dr. Hal Raglan, who has developed a method of exorcising deep-seated psychological issues using a technique called “psychoplasmics.” In intense one-on-one sessions reminiscent of psychodrama, Raglan is able to physically remove trauma from the human body in the form of ulcers, rashes, and, we eventually discover, cancer. In the ultimate reveal, it’s shown that Raglan has helped traumatized patient Nola Carveth (Samantha Eggar) to birth violent, deformed homunculi who go out into the world, psychically connected to her, in order to resolve her childhood abandonment issues and abuse with bloody murder. Raglan’s foundation, the Somafree Institute of Psychoplasmics (its name simultaneously evocative of Aldous Huxley’s perfect drug soma, and reminiscent of fringe psychological research like Wilhelm Reich’s orgone theory) inhabits a modernist chalet far outside the city of Toronto. Non-resident patients have to be bussed in. Raglan’s public reputation is that of an eccentric, but effective, therapist. At several points in the film we see the covers of Raglan’s presumably best-selling The Shape of Rage. (Curiously, a decade later, in 1990, a documentary titled Child of Rage would be released covering the controversial use of “attachment therapy.”)

As depicted in the film, Somafree is not a corporation. But the thematic threads surrounding Raglan and his Institute are based on real-life trends in the 1970s. In its practices and in the person of Raglan, Somafree resembles psycho-intensive institutes like Esalen, self-improvement organizations like Lifespring, and personalities like Werner Erhard. Erhard’s est movement used primal abuse to ostensibly create psychological breakthroughs, helping the “patient” become more assertive, more powerful, less prone to obeying impulses caused by their early traumas. There is also the real-life analogue to the psychological method that Raglan employs: psychodrama. In the 1970s, new methods of conflict resolution pioneered in places like Esalen were beginning to seep into the mainstream of North American society. These methods soon spread into the corporate world as a purported means of defusing tensions at work and making an office more productive. The “encounter group” soon became a punchline, but the principles behind the Age of Aquarius’s more touchy-feely psychodynamic methods soon became part of the warp and weft of corporate culture in the ’80s and well beyond.

Nola’s estranged husband Frank interviews a former Raglan patient, Jan Hartog, in an attempt to discredit Somafree so Frank can regain custody of his daughter. This patient bears the scars of Raglan’s work on him: a lymphatic cancer sprouting from his neck (an eerie foreshadowing of the coming of another mysterious lymphatic disorder that would soon break out all over North America). Hartog plans to sue; not to achieve victory in a courtroom, but to destroy Raglan’s reputation. It doesn’t matter if they win, Hartog says, because “They’ll just remember the slogan. Psychoplasmics can cause cancer.” The 1970s was full of an increased awareness of the carcinogens that surrounded us in the late-industrial West—cigarettes, sweeteners, food dyes, and pesticides—thanks in large part to the nascent environmental and consumer rights movements, which faced off against corporations using weapons of negative publicity.

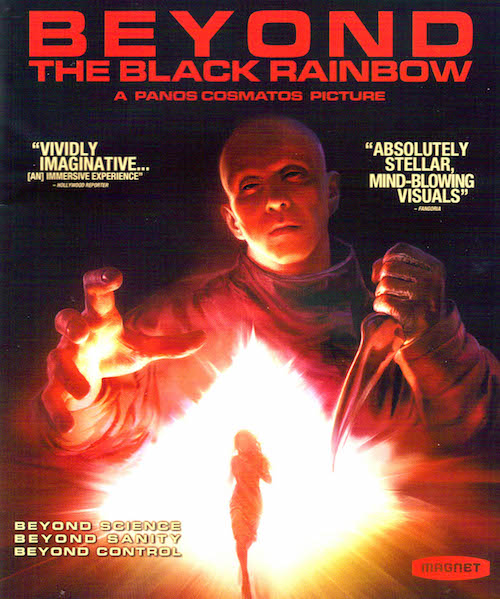

By the time we get to Scanners in 1981, we are fully invested in a world of shadowy corporate overlords. A huge multinational security firm, ConSec, tries to shepherd psychics called “scanners,” ostensibly to help them control their powers, but also to utilize and exploit their paranormal abilities. Protagonist Cameron Vale (Steven Lack) is apprehended off the streets, where, due to his psychic pain, he’s living as a derelict. We learn that scanners don’t “fit in” with society. When Vale is given the inhibitive drug ephemerol by ConSec’s head of scanner research, Dr. Paul Ruth (Patrick McGoohan), he is able to get himself together and is even given a new proto-yuppie wardrobe and mission by ConSec: eliminate rogue scanner Darryl Revok (Michael Ironside). But as Vale accepts his mission and new identity, he finds himself enlisted in ConSec’s private war against renegade scanners. When he runs into an emerging cell of scanners who are forming a powerful “group mind” in a New Age-like encounter session, assassins controlled by Revok murder most of the cell. “Everywhere you go, somebody dies,” one of the hive mind tells Vale, who is complicit with ConSec’s need to exert corporate control over scanners, including the use of violence as part of the corporate mission. Meanwhile, ConSec itself is riddled with moles working with Revok. Indeed, a chemical and pharmaceutical company called “Biocarbon Amalgamate,” founded by Dr. Ruth but now infiltrated by Revok, manufactures ephemerol in massive quantities. Scanners recontexualizes the Cold War espionage “wilderness of mirrors” in terms of corporate espionage for a new age of corporate domination. (It’s no coincidence that Cronenberg cast McGoohan, one of the Cold War’s most famous fictional spies, in the role of Dr. Ruth.)

ConSec’s corporate mission is revealed in a board meeting when the new head of security says, “We’re in the business of international security. We deal in weaponry and private armories.” This head of security also tells Dr. Ruth, “Let us leave the development of dolphins and freaks as weapons of espionage to others.” To the new breed of ConSec executive, fringe ’70s research is a thing of the past, despite its obvious power and relevance. The future is in fighting proxy wars, ensuring private security for the wealthy, and providing mercenary security forces. ConSec in this way is like many other private security firms that first emerged in the 1970s and ’80s. Begun as an outgrowth of post-colonial British military adventurism, the private military company soon became a way for ex-military officers to assure themselves a handsome post-service sinecure in a new era where hot wars were a thing of the past. “Brushfire wars” would continue to ensue, ensuring these companies an expanding portfolio, both in the waning years of the Cold War and in the 1990s and beyond. In fact, it’s interesting to note that many of the real-world military’s supposed psychic assets themselves got into private security after the U.S. Army shut down fringe science projects like Project STARGATE. Art imitates life imitates art.

Videodrome expands Cronenberg’s conspiratorial corporate, military, and espionage worldview into the rapidly exploding world of the media in the early ’80s. Leaps forward in technology, all of which are explicitly called out in Videodrome, litter the film’s visual landscape. Cable television, satellite transmissions (and the attendant hacking thereof), video cassette recorders, the rise of video pornography, virtual reality, postmodern media theory, and violence in entertainment all play essential roles in the film. Max Renn’s (James Woods) tiny Civic TV/Channel 83 (itself based on groundbreaking independent Toronto television station CityTV) is trying to survive as best it can in a world of massive international media players. Ever seeking the latest hit that will tap into the public’s unending hunger for sex and violence, his on-staff “satellite pirate” Harlan delivers the mysterious Videodrome transmission. Harlan is later revealed to be working with the Videodrome conspiracy, having intentionally exposed Max to the signal. In a memorable speech, Harlan nails Max’s amoral desire to sell sex and violence to his viewers: “This cesspool you call a television station, and your people who wallow around in it, and your viewers who watch you do it; you’re rotting us away from the inside.” When Renn is deep into his Videodrome-triggered hallucinations, he is offered corporate “help” much as Cameron Vale was. This time, his “savior” is Barry Convex, a representative of Spectacular Optical. In his video message to Max, he, like the ConSec executive before him, lays out Spectacular Optical’s corporate mission:

I’d like to invite you into the world of Spectacular Optical, an enthusiastic global corporate citizen. We make inexpensive glasses for the Third World… and missile guidance systems for NATO. We also make Videodrome, Max.

The final form of the military-industrial-entertainment complex is laid bare. Videodrome’s intent is to harden and make psychotic a North American television audience who’ve “become soft,” as Harlan puts it. Renn’s hallucinations are recorded, he is literally “reprogrammed” to kill Civic TV’s board (thanks to the memorable hallucinatory image of Convex sticking a VHS tape into Renn’s gut). Renn is then reprogrammed to retaliate and assassinate Convex by the much more ’70s-cult Cathode Ray Mission of “media prophet” Brian O’Blivion, whose postmodern, expressly McLuhanesque view of television’s place in the world allowed Videodrome to come into existence in the first place: “I had a brain tumor and I had visions. I believe the visions caused the tumor and not the reverse… when they removed the tumor, it was called Videodrome.” It’s also worth noting that O’Blivion tells us that Videodrome made him its first victim; postmodern criticism of the medium of television is no match for its violent, cancerous growth.

The deregulation of media in the U.S. in the Reagan years is common knowledge; rules around children’s television were especially eviscerated, which allowed for an explosion in violent, warlike cartoons based on popular toy lines, training a new generation for a lifetime of endless war. Combined with the aforementioned explosion of video technology, the laissez-faire environment shepherded by Reagan’s FCC allowed a new breed of cable television magnates to get rich and created a television and media landscape with a relatively friction-free relationship to government. By the time the first Gulf War broke out in 1991, war provided the cable news networks with surefire ratings and cable news provided the propaganda platform for the war effort, a mutually beneficial (and Cronenberg-esque) symbiosis that’s continued to metastasize through multiple subsequent wars in the Middle East. The world of Videodrome, the one Harlan evokes where America will no longer be soft in a world full of tough hombres, has finally come to fruition thanks in part to all of our enmeshment in the video arena—the video drome.

After Videodrome—in The Fly (1986), Dead Ringers (1988), and Crash (1996)—Cronenberg focuses less on sinister organizations and more on monomaniacal researchers, doctors, and fetishists who pursue their individual idiosyncratic agendas through the director’s trademark twisting mindscapes (and bodyscapes). With the exception of eXistenZ (1999), Cronenberg’s meditation on computer technology and gaming released amidst the first dot-com bubble, and his Occupy-influenced adaptation of Don DeLillo’s 2003 novel Cosmopolis (2012), he has retreated from a more overt suspicion of corporations and shadowy conspiracies. His warning about these invisible masters pulling the strings of society came during the time period when something could have been done about corporate hegemony. But now, the conspiracy operates in the open. We are now all of us the dumb, trusting Cronenberg protagonist, lulled into a false sense of security by a series of “enthusiastic corporate citizens.” Long live the new flesh.