A Scanner Darkly

By Brian Eggert

Source: Deep Focus Review

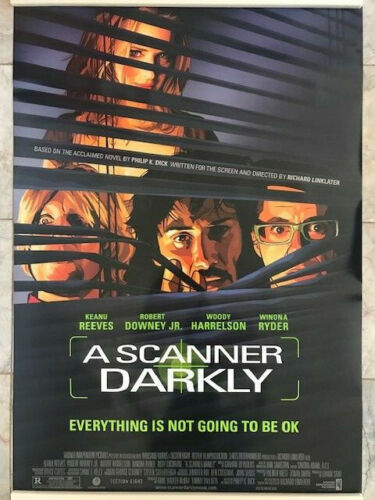

Based on the acclaimed novel by Philip K. Dick, Richard Linklater’s 2006 film of A Scanner Darkly presents a cautionary tale on drugs, surveillance, and perception in a unique formal arrangement. Set “seven years from now,” the film considers a tyrannical post-9/11 world oppressed by an ever-watchful government, widespread paranoia, corporate subjection, and pervasive pharmaceutical addiction—all elements further fuelled by the obsessive fear that governments, corporations, and even your friends conspire against you. Linklater’s decision to produce his film with rotoscoped animation turns his adaptation into one of the most visually and thematically original motion pictures in decades, and the most faithful of all Dick adaptations. The film’s world contains several Dickian existential and metaphysical dilemmas and paradoxes, from the notion of spying on oneself to becoming willing participants in one’s drug addiction. This unsettling and tragic world becomes deliciously skewed from the excessive filtering of surveillance technology and a crazed dystopian culture, so much so that it remains impossible to see anyone for who or what they really are. A Scanner Darkly beautifully, and chillingly, considers Dick’s persistent theme that our culture has destroyed its own ability to perceive objective reality.

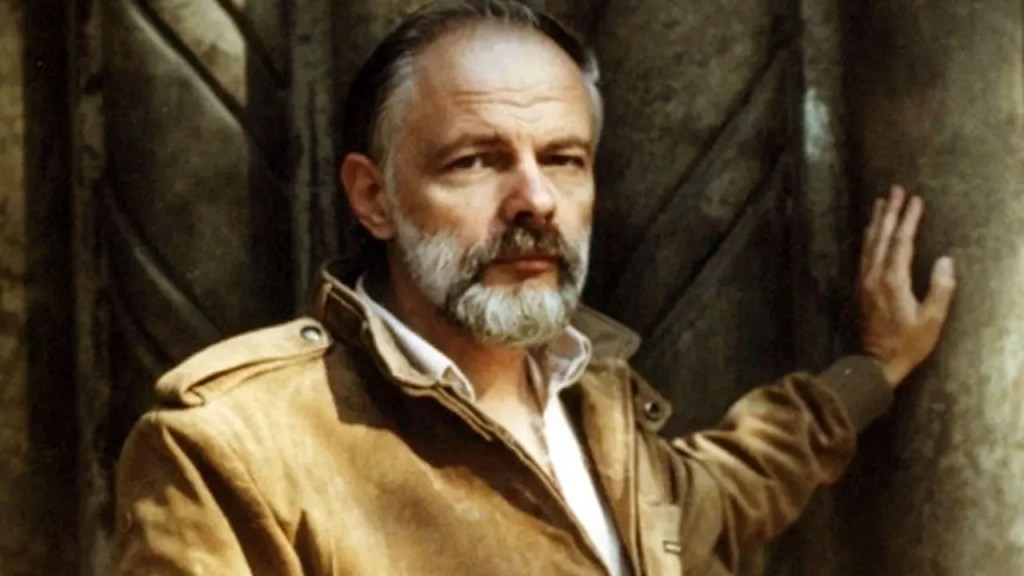

Philip K. Dick was born in 1928 and became interested in science fiction at an early age. He attended the Berkeley, California, high school and graduated in 1947, alongside another future science fiction author, Ursula K. Le Guin, and briefly attended the University of California, Berkeley. He published his first science fiction story in 1951. From there on out, he would become one of the most prolific authors in his genre, publishing some 44 novels and more than 100 short stories until his death in 1982, just before the release of his first book-to-film adaptation, Blade Runner, based on his 1966 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Though science fiction was typically considered unsophisticated and a lower form of fiction, Dick’s caustic wit and social satires elevated sci-fi to the level of art. His self-proclaimed title was not that of an author but rather a truth-teller. He wrote his truth, and it consisted of a vast fictionalized philosophy, which some might argue was—and is—not necessarily fiction. His most enthusiastic followers might say his work is visionary, if not prophetic. Dick claimed his work spoke, and still speaks, to disturbed, troubled, and “off” members of society. His writing is for those who cannot rationalize society or reality: for those who need a satire, base, or frame of reference to rely on as coping mechanisms. Science fiction creates the desired satirical reality for readers, just as his characters in A Scanner Darkly see drugs as the only sane choice to escape the insane world.

Written in 1977, A Scanner Darkly stands as an ode to the drug counter-culture of Dick’s own Berkeley underground. But it’s also a thoughtful exploration of the metaphysical existence of drug users, as well as a mournful commentary on the government’s involvement in drug culture. Standing against the blatantly autocratic Nixon administration, marked by a reputation for undue suspicion and conspicuous surveillance, his Berkeley group purveyed conspiracy theories and widespread mistrust. And yet, this counter-culture also included a vast set of respected thinkers, unafraid to speak out—not just mindless stoners. According to an interview with French TV, Dick claims the group’s paranoia was not unjustified. During the interview, Dick speaks of secret CIA and FBI files on him, covert operations to get at his personal documents, and rampant spying led by the heads of various government organizations. To Nixon and his administration, the Berkeley group was an unknown element—a misunderstood collection of hippies seen through a distorted set of the administration’s famously paranoid views and political mechanisms. Fuelling this conflict between the two factions of Nixon’s administration and the Berkeley group, the author had a lifetime’s worth of experience with drugs, psychosis, and a slight case of schizophrenia. But in no way should those characteristics hinder the author’s message. Instead, Dick’s distinctiveness within the Berkeley group should reinforce that A Scanner Darkly may be more autobiographical than his other novels.

The story’s main character is Bob Arctor (Keanu Reeves), an addict of a drug called Substance D, also known as Slow Death. But Bob is also Fred, an undercover narc spying on Arctor’s group of Substance D-using friends. Arctor has lost sight of his identity because of Substance D, which chemically separates brain functions in the hemispheres; after prolonged use, the left and right sides of his brain are unaware of each other. Furthermore, the Fred portion of the main character must conceal his identity from his supervisors for his own safety. No one knows who Fred is; no one knows who Bob is—including himself. The sole man representing both the narc and the addict does not realize he is spying on himself, and in a way, informing on himself. This self-betrayal is tantamount to suicide, rendering him prey to both Substance D and the totalitarian police state that employs him. According to the novel, the drug is made from a flower called “mors ontological”—Latin for ontological death. To be sure, Dick saw first-hand the damage substance abuse caused his friends. He was not entirely unaffected himself; he relied on methamphetamines and psychedelics for much of his early career. But he weaned himself off drugs before writing this book. And at the very end of his novel, Dick dedicates his fiction to several friends who died or retained permanent physical and mental dysfunction due to excessive drug use (a dedication abbreviated at the end of Linklater’s film). He writes that users are punished excessively and even unknowingly for attempting to “play” with something dangerous.

So often, society deems drug users worthless or mindless junkies for their habits, but A Scanner Darkly—the story and the title itself—asks that we do not pass judgment until we can see, in its entirety, the role of users. However, because of the elaborate system of filters between our eyes and that which we wish to see, how can we ever trust that we see reality and not some malformed version of reality skewed through surveillance tools? These filters exist in the form of monitoring equipment such as cameras and scanners, but also the mind-altering Substance D. Drugs are the obscuring mechanism by which the narrative challenges audiences to accept and ultimately forgive the characters within. Throughout the film, viewers must accept drug use as a fact of the story rather than a downfall of the characters. The book’s title refers to a verse from the bible, namely 1 Corinthians 13: 11-12, a verse that is paradoxically read both at weddings and funerals:

For we know in part, and we prophesy in part. But when that which is perfect is come, then that which is in part shall be done away. When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now, we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.

A pattern of dualism exists in this passage, particularly after its application to popular culture. Both in the novel and the film of A Scanner Darkly (not to mention Swedish director Ingmar Bergman’s film Through a Glass Darkly), the idea of childhood versus adulthood, known and knowing, and parts versus the whole, are circumscribed so that the reader or audience cannot reconcile metonym from metaphor.

Dick’s writing often tells of worlds that are not what they seem. With A Scanner Darkly, the world remains undefined, distorted through a complicated filtration process. Linklater magnificently captures that undercurrent through his use of rotoscoped animation. Throughout the narrative, we remain unsure about Reeves’ character’s identity—in part due to the setting’s massive use of surveillance technology. The protagonist is not altogether Bob, nor is he altogether Fred; he comprises several constructs that never assemble into a single, understandable symbol. Agent Fred watches Bob on numerous holo-scanners, located everywhere; scanners see every moment of every day in every location. Someone is always watching (or that is what they want you to think). Undoubtedly, there was a time when Fred realized he was Bob, but Substance D has destroyed his understanding of his dual roles. Now, Fred cannot fully understand or see Bob. Who is this mysterious figure? Fred wonders. Is he the mastermind behind the whole thing? When Fred looks, he watches through a filter: the scanner. He cannot see clearly because his mind has been altered. At the same time, Bob has an unsettling sensation that he’s being watched. Though Bob and Fred are the same person, they cannot fully understand themselves. Meanwhile, the overwhelming network of observational devices only puts the truth at a greater distance.

The main character questions his culture’s scoptophilia-driven ways of looking and its authenticity: “What does a scanner see?” he asks himself. “Into the head? Down into the heart? Does it see into me? Into us? Clearly or darkly? I hope it sees clearly because I can’t any longer see into myself. I see only murk. I hope for everyone’s sake the scanners do better, because if the scanner sees only darkly the way I do, then I’m cursed and cursed again, too.” The protagonist’s hopes are in vain, as scanners prevent authorities from seeing their suspects clearly. Drugs debatably prevent the film’s main characters from seeing reality clearly, just as Linklater’s innovative use of animation in the film prevents audiences from seeing clearly. All these devices—scanners, drugs, animation—are filtering devices within the film. They distance the viewer or the subject from the truth, for which knowledge thereof is impossible, thus brilliantly placing us on the same disjointed plane of existence as the protagonist. We see through these filters as if a sfumato haze lingered between our eyes, and what we see is a distortion that impedes an accurate understanding.

With the film’s animation, the distortion does not take away from the audience’s understanding of the story’s message. It adds to it. The rotoscoping technique postponed the film’s scheduled release yet made the lengthy, nearly two-year production worth every moment to waiting audiences. A Scanner Darkly’s journey to the screen actually struggled for well over a decade with interested directors and forgotten scripts. In the 1990s, filmmakers ranging from Terry Gilliam to David Cronenberg attempted but failed to get their proposed adaptation before cameras. Charlie Kaufman, the writer of Being John Malkovich and the very Philip K. Dick-esque Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, also wrote a screenplay for Dick’s much-praised drug novel, although the script was never produced. Eventually, writer and director Richard Linklater wrote an adaptation. He had previously wanted to adapt Dick’s fast-paced Ubik, but settled on A Scanner Darkly for its metaphysical pondering and sense of paranoia, both themes which Linklater had explored before. George Clooney and Steven Soderbergh’s production company Section Eight agreed to produce. And eventually, the film was sanctioned by the Philip K. Dick Trust.

Based in Austin, Texas, Linklater helped launch a movement in American independent cinema with his 1991 debut, Slacker, an ultra-low-budget film that follows a group of college-age thinkers and vagabonds in loosely connected conversational vignettes. Before that, Linklater demonstrated his love of cinema when he founded The Austin Film Society in 1985, a non-profit group devoted to rare and important filmic works, which today has an Advisory Board consisting of filmmakers such as Steven Soderbergh, Quentin Tarantino, Robert Rodriguez, Tobe Hooper, and Les Blank. After Slacker, Linklater released Dazed and Confused (1993), a box-office flop that has since become a cult favorite, along with launching the careers of Ben Affleck, Matthew McConaughey, and Parker Posey. He continued with films rooted in thoughtful conversations, such as Before Sunrise (1995), the first chapter in the transcendent Before trilogy, and subUrbia (1997), adapted from Eric Bogosian’s acidic play. Eventually, Linklater experimented with commercial work, such as The Newton Boys (1998), an underwhelming Prohibition-era bank robber story, and the underrated Jack Black comedy School of Rock (2003). But the writer-director’s real talents flourish in artistic films with a sly commercial appeal—such as the highly praised sequels to Before Sunrise, 2004’s Before Sunset and 2013’s Before Midnight; his part-documentary, part-dramatized real-life murder story Bernie (2011); or his ambitious 12-year project Boyhood (2014).

Outwardly, A Scanner Darkly remains most closely tied to Linklater’s 2001 release, Waking Life, a most meandering and philosophizing work that uses rotoscoped animation to follow an ongoing series of thought-provoking conversations. The process was originally used in 1914 by cartoonist Max Fleischer, and then next by Walt Disney, to help cartoonists simulate natural movement. By painting or inking on live-action footage, the characters in a film such as Sleeping Beauty (1959) were given more realistic bodily actions and facial expressions. But A Scanner Darkly would use the method for much more than merely painting over photography; the film uses animation to establish both reality and create hallucinatory images. As a result, the original plan scheduled nine months’ worth of post-production animation, but the process took eighteen months to allow for the detail and imagination Linklater wanted in his animation. The outcome, even in seemingly insignificant scenes, is breathtaking. The flawless animation appears to be a comic book with a pulse. Combine that with the bravado performances of the film’s actors, and the animation becomes just another piece of the apparatus that disappears in the glory of a great story. Some may hold reservations towards the technique, believing that the animation takes away from the actors’ performances or the narrative. Still, the approach helps rather than hinders the actors’ places in A Scanner Darkly’s bizarre, paranoid reality, aligning perfectly with Dick’s themes of reality distortion.

The most impressive piece of animation in the picture is Fred’s ever-shifting “scramble suit,” which prevents Fred’s supervisors from identifying him, maximizing the security of his cover. Fred’s boss wears a similar suit, and neither Fred nor his boss knows who is behind the other’s suit. The “scramble suit” projects false identities via constantly shifting characteristics so that no surveillance mechanism can pinpoint the wearer’s identity, therein eliminating any possibility of exposure. Animating the suit consists of creating hundreds, if not thousands, of facial and bodily fragments that dizzily rotate at random. But each momentary identity has to maintain an overall silhouette and still project the actor underneath. When Keanu Reeves’ Fred moves, even from under the continually changing scramble suit, the audience can still recognize Reeves’ movements and body language. The performances themselves were given by actors chosen not only for their sheer talent but, seemingly, for their off-screen reputation with drugs. Keanu Reeves, Robert Downey Jr., Woody Harrelson, Winona Ryder, and Rory Cochrane have all had or even lived similar roles to theirs in A Scanner Darkly. Somehow rotoscoping wipes away that stigma, compiling a new face literally painted over the actor’s old one. The performers are made whole again, permitting the audience to forget about Downey Jr.’s reoccurring drug problems or Harrelson’s history with pot. They are no longer actors but rather characters given free-range because of the innovative medium. Their off-screen reputations linger in our subconscious, to be remembered later upon reflecting on the film’s artistry.

The most notable performance of the group is Robert Downey Jr. as Barris—a suspicious character so burnt out from the drugs and constant onslaught of paranoia that he’s become sadistically mistrusting, if only internally, of his friends. Downey Jr. plays Barris as a fast-talking, often brilliant individual that can turn at any moment. Downey’s maniacal rapid-flow speech and brazen waving of the arms bring Barris—the most conniving, intelligent, humorous, sadistic, and strangely most likable character from the novel—to life. Reeves and Cochrane’s performances deserve acknowledgment as well, as each actor completely embodies their respective role. Reeves takes Bob (or is it Fred, or later Bruce?) to the ambiguous level demanded. While Reeves has taken his share of guff for his inexpressive acting, he seems at ease and perfectly cast here. Looking back, no other actor could have given Bob-Fred-Bruce the same ambivalence to the world and himself without making it appear too unintentional (or too intentional, for that matter). Cochrane plays Freck, an overdosing Substance D fiend and one of Arctor’s group of stoner friends. The first scenes in the film involve Freck attempting to wash and kill hallucinatory aphids from his body and out of his hair. Cochrane gives Freck the perfect helpless-yet-fearful twitch of a user who knows he has gone too far. Freck is pitiable in how prey is pitiable: although aware of his deteriorating state, he is too far gone to change the situation and helpless to prevent his eventual collapse.

This could be said for any of the characters in the film. Each floats like a moth on a calm pond—having landed on the water, they are now helpless to escape. They wait for some hideous predator from the murky bottom to float up and gulp them down. Both the film and Dick’s novel share a potent message—particularly in the story’s climax, which reveals that the foundation set up to cure people of Substance D addiction is the very organization creating it, a corporation called New Path. This turn speaks against the type of suspicious world where people have no choice but to escape. Neither the film nor the book condones drug use, but they understand it. They do not blame users for attempting to distract themselves from the ever-encroaching watchful eye of society and the government looming in. Or as Dick writes in his Author’s Note at the end of his novel:

Like children playing in the street; they could see one after another of them being killed—run over, maimed, destroyed—but they continued to play anyway. We really all were very happy for a while, sitting around not toiling but just bullshitting and playing, but it was for such a terrible brief time, and then the punishment was beyond belief; even when we could see it, we could not believe it.

Indeed, through A Scanner Darkly, Dick seems to indirectly remark on the allegations that the CIA participated in the Secret War in Laos, which in turn moved commercial opiates, including heroin, into the United States. Those who wished to “play” could do so thanks to their government, and in turn, they were destroyed for it. Surely Dick’s story would anticipate accusations of CIA cocaine trafficking, specifically during the Reagan and Clinton administrations: there are questions about how closely the government has worked alongside the Mexican Cartels; how the CIA has allowed drop points at the Mena Intermountain Municipal Airport; if the CIA collaborated to import cocaine and marijuana as part of the Contra war in Nicaragua; or how the CIA targeted certain Black neighborhoods during the 1980s crack epidemic. But, as with Freck and eventually Bob, we do not judge the users in A Scanner Darkly; instead, we see them as the product of ignorance, corruption, and an irresponsible government. Dick and his Berkeley group, which one can imagine were not dissimilar from Arctor’s group, were neither victims nor criminals for their usage.

Even today, several decades after his death, Dick’s work remains futurist and visionary, yet also reflective of our society. Since Blade Runner‘s release in 1982, Dick has become one of the most adapted-to-film authors, from Paul Verhoeven’s ruthless actioner Total Recall (1990, based on Dick’s short story “We Can Remember It For You Wholesale”) to Steven Spielberg’s breathless thriller Minority Report (2002, based on the short story of the same name). More recently, Amazon has turned Dick’s Hugo Award-winning book The Man in the High Castle into a triumphant series. But where other adaptations often abandon the author’s insights on the nature and illusion of existence in favor of sci-fi genre fun, Linklater’s A Scanner Darkly fully embraces Dick’s penchant for damaged souls and their metaphysical line of questioning. Linklater’s film has been praised, even by Philip K. Dick’s daughter Isa, as an accurate, generous, and artistic adaptation. Unfortunately, Dick’s work has a notorious reputation for being slaughtered by screenwriters, as viewers of Paycheck (2003) and Next (2007) can attest. The few good adaptations out there still stray from the writer’s original text, though in spirit, they remain faithful. But Linklater captured the plot, spirit, and most importantly, the questions of Dick’s original work. Instead of losing himself in science-fiction, he used the book to emphasize further the story’s focus on a particular subculture and what races through their minds.

Wondrous and curious sights are shown in this film—so wondrous that, quite intentionally, we begin to mistrust our eyes. When we cannot trust what we see and how we feel, when we suspect our senses, and when a world like the one depicted in A Scanner Darkly succeeds so well in drawing us in and making us as paranoid as its characters, we find ourselves involved in the story more so than we realized. Therein lies the subtle genius of A Scanner Darkly. Like the characters in the film, we’re involved in the long, drug-fueled conversations and skewed perceptions of reality, forgetting about the inherent dangers until all at once, we realize that Freck, Arctor, and eventually the rest, will succumb to a slow death. The film’s last shots are at once melancholy and hopeful. They find Arctor inside one of New Path’s many farms that produce the flower behind Substance D, though his brain has been fried beyond help. Perhaps, somehow, his presence and police work will lead to New Path’s end. Or perhaps not. Linklater superbly captures the sobering theme of Dick’s novel—how people are forced to rely on escape, either from their own psychosis or the world around them. Ultimately, they become willing casualties of their own addiction and complicit in their own demise; through their attempt to escape, they turn themselves into slaves of the very system they hoped to avoid.

____________________