Economists believe in full employment. Americans think that work builds character. But what if jobs aren’t working anymore?

By James Livingston

Source: aeon

Work means everything to us Americans. For centuries – since, say, 1650 – we’ve believed that it builds character (punctuality, initiative, honesty, self-discipline, and so forth). We’ve also believed that the market in labour, where we go to find work, has been relatively efficient in allocating opportunities and incomes. And we’ve believed that, even if it sucks, a job gives meaning, purpose and structure to our everyday lives – at any rate, we’re pretty sure that it gets us out of bed, pays the bills, makes us feel responsible, and keeps us away from daytime TV.

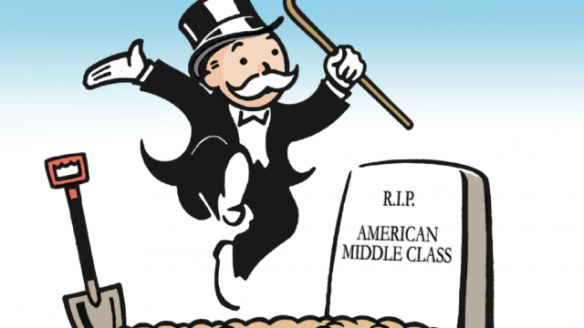

These beliefs are no longer plausible. In fact, they’ve become ridiculous, because there’s not enough work to go around, and what there is of it won’t pay the bills – unless of course you’ve landed a job as a drug dealer or a Wall Street banker, becoming a gangster either way.

These days, everybody from Left to Right – from the economist Dean Baker to the social scientist Arthur C Brooks, from Bernie Sanders to Donald Trump – addresses this breakdown of the labour market by advocating ‘full employment’, as if having a job is self-evidently a good thing, no matter how dangerous, demanding or demeaning it is. But ‘full employment’ is not the way to restore our faith in hard work, or in playing by the rules, or in whatever else sounds good. The official unemployment rate in the United States is already below 6 per cent, which is pretty close to what economists used to call ‘full employment’, but income inequality hasn’t changed a bit. Shitty jobs for everyone won’t solve any social problems we now face.

Don’t take my word for it, look at the numbers. Already a fourth of the adults actually employed in the US are paid wages lower than would lift them above the official poverty line – and so a fifth of American children live in poverty. Almost half of employed adults in this country are eligible for food stamps (most of those who are eligible don’t apply). The market in labour has broken down, along with most others.

Those jobs that disappeared in the Great Recession just aren’t coming back, regardless of what the unemployment rate tells you – the net gain in jobs since 2000 still stands at zero – and if they do return from the dead, they’ll be zombies, those contingent, part-time or minimum-wage jobs where the bosses shuffle your shift from week to week: welcome to Wal-Mart, where food stamps are a benefit.

And don’t tell me that raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour solves the problem. No one can doubt the moral significance of the movement. But at this rate of pay, you pass the official poverty line only after working 29 hours a week. The current federal minimum wage is $7.25. Working a 40-hour week, you would have to make $10 an hour to reach the official poverty line. What, exactly, is the point of earning a paycheck that isn’t a living wage, except to prove that you have a work ethic?

But, wait, isn’t our present dilemma just a passing phase of the business cycle? What about the job market of the future? Haven’t the doomsayers, those damn Malthusians, always been proved wrong by rising productivity, new fields of enterprise, new economic opportunities? Well, yeah – until now, these times. The measurable trends of the past half-century, and the plausible projections for the next half-century, are just too empirically grounded to dismiss as dismal science or ideological hokum. They look like the data on climate change – you can deny them if you like, but you’ll sound like a moron when you do.

For example, the Oxford economists who study employment trends tell us that almost half of existing jobs, including those involving ‘non-routine cognitive tasks’ – you know, like thinking – are at risk of death by computerisation within 20 years. They’re elaborating on conclusions reached by two MIT economists in the book Race Against the Machine (2011). Meanwhile, the Silicon Valley types who give TED talks have started speaking of ‘surplus humans’ as a result of the same process – cybernated production. Rise of the Robots, a new book that cites these very sources, is social science, not science fiction.

So this Great Recession of ours – don’t kid yourself, it ain’t over – is a moral crisis as well as an economic catastrophe. You might even say it’s a spiritual impasse, because it makes us ask what social scaffolding other than work will permit the construction of character – or whether character itself is something we must aspire to. But that is why it’s also an intellectual opportunity: it forces us to imagine a world in which the job no longer builds our character, determines our incomes or dominates our daily lives.

In short, it lets us say: enough already. Fuck work.

Certainly this crisis makes us ask: what comes after work? What would you do without your job as the external discipline that organises your waking life – as the social imperative that gets you up and on your way to the factory, the office, the store, the warehouse, the restaurant, wherever you work and, no matter how much you hate it, keeps you coming back? What would you do if you didn’t have to work to receive an income?

And what would society and civilisation be like if we didn’t have to ‘earn’ a living – if leisure was not our choice but our lot? Would we hang out at the local Starbucks, laptops open? Or volunteer to teach children in less-developed places, such as Mississippi? Or smoke weed and watch reality TV all day?

I’m not proposing a fancy thought experiment here. By now these are practical questions because there aren’t enough jobs. So it’s time we asked even more practical questions. How do you make a living without a job – can you receive income without working for it? Is it possible, to begin with and then, the hard part, is it ethical? If you were raised to believe that work is the index of your value to society – as most of us were – would it feel like cheating to get something for nothing?

We already have some provisional answers because we’re all on the dole, more or less. The fastest growing component of household income since 1959 has been ‘transfer payments’ from government. By the turn of the 21st century, 20 per cent of all household income came from this source – from what is otherwise known as welfare or ‘entitlements’. Without this income supplement, half of the adults with full-time jobs would live below the poverty line, and most working Americans would be eligible for food stamps.

But are these transfer payments and ‘entitlements’ affordable, in either economic or moral terms? By continuing and enlarging them, do we subsidise sloth, or do we enrich a debate on the rudiments of the good life?

Transfer payments or ‘entitlements’, not to mention Wall Street bonuses (talk about getting something for nothing) have taught us how to detach the receipt of income from the production of goods, but now, in plain view of the end of work, the lesson needs rethinking. No matter how you calculate the federal budget, we can afford to be our brother’s keeper. The real question is not whether but how we choose to be.

I know what you’re thinking – we can’t afford this! But yeah, we can, very easily. We raise the arbitrary lid on the Social Security contribution, which now stands at $127,200, and we raise taxes on corporate income, reversing the Reagan Revolution. These two steps solve a fake fiscal problem and create an economic surplus where we now can measure a moral deficit.

Of course, you will say – along with every economist from Dean Baker to Greg Mankiw, Left to Right – that raising taxes on corporate income is a disincentive to investment and thus job creation. Or that it will drive corporations overseas, where taxes are lower.

But in fact raising taxes on corporate income can’t have these effects.

Let’s work backward. Corporations have been ‘multinational’ for quite some time. In the 1970s and ’80s, before Ronald Reagan’s signature tax cuts took effect, approximately 60 per cent of manufactured imported goods were produced offshore, overseas, by US companies. That percentage has risen since then, but not by much.

Chinese workers aren’t the problem – the homeless, aimless idiocy of corporate accounting is. That is why the Citizens United decision of 2010 applying freedom of speech regulations to campaign spending is hilarious. Money isn’t speech, any more than noise is. The Supreme Court has conjured a living being, a new person, from the remains of the common law, creating a real world more frightening than its cinematic equivalent: say, Frankenstein, Blade Runner or, more recently, Transformers.

But the bottom line is this. Most jobs aren’t created by private, corporate investment, so raising taxes on corporate income won’t affect employment. You heard me right. Since the 1920s, economic growth has happened even though net private investment has atrophied. What does that mean? It means that profits are pointless except as a way of announcing to your stockholders (and hostile takeover specialists) that your company is a going concern, a thriving business. You don’t need profits to ‘reinvest’, to finance the expansion of your company’s workforce or output, as the recent history of Apple and most other corporations has amply demonstrated.

So investment decisions by CEOs have only a marginal effect on employment. Taxing the profits of corporations to finance a welfare state that permits us to love our neighbours and to be our brothers’ keeper is not an economic problem. It’s something else – it’s an intellectual issue, a moral conundrum.

When we place our faith in hard work, we’re wishing for the creation of character; but we’re also hoping, or expecting, that the labour market will allocate incomes fairly and rationally. And there’s the rub, they do go together. Character can be created on the job only when we can see that there’s an intelligible, justifiable relation between past effort, learned skills and present reward. When I see that your income is completely out of proportion to your production of real value, of durable goods the rest of us can use and appreciate (and by ‘durable’ I don’t mean just material things), I begin to doubt that character is a consequence of hard work.

When I see, for example, that you’re making millions by laundering drug-cartel money (HSBC), or pushing bad paper on mutual fund managers (AIG, Bear Stearns, Morgan Stanley, Citibank), or preying on low-income borrowers (Bank of America), or buying votes in Congress (all of the above) – just business as usual on Wall Street – while I’m barely making ends meet from the earnings of my full-time job, I realise that my participation in the labour market is irrational. I know that building my character through work is stupid because crime pays. I might as well become a gangster like you.

That’s why an economic crisis such as the Great Recession is also a moral problem, a spiritual impasse – and an intellectual opportunity. We’ve placed so many bets on the social, cultural and ethical import of work that when the labour market fails, as it so spectacularly has, we’re at a loss to explain what happened, or to orient ourselves to a different set of meanings for work and for markets.

And by ‘we’ I mean pretty much all of us, Left to Right, because everybody wants to put Americans back to work, one way or another – ‘full employment’ is the goal of Right-wing politicians no less than Left-wing economists. The differences between them are over means, not ends, and those ends include intangibles such as the acquisition of character.

Which is to say that everybody has doubled down on the benefits of work just as it reaches a vanishing point. Securing ‘full employment’ has become a bipartisan goal at the very moment it has become both impossible and unnecessary. Sort of like securing slavery in the 1850s or segregation in the 1950s.

Why?

Because work means everything to us inhabitants of modern market societies – regardless of whether it still produces solid character and allocates incomes rationally, and quite apart from the need to make a living. It’s been the medium of most of our thinking about the good life since Plato correlated craftsmanship and the possibility of ideas as such. It’s been our way of defying death, by making and repairing the durable things, the significant things we know will last beyond our allotted time on earth because they teach us, as we make or repair them, that the world beyond us – the world before and after us – has its own reality principles.

Think about the scope of this idea. Work has been a way of demonstrating differences between males and females, for example by merging the meanings of fatherhood and ‘breadwinner’, and then, more recently, prying them apart. Since the 17th century, masculinity and femininity have been defined – not necessarily achieved – by their places in a moral economy, as working men who got paid wages for their production of value on the job, or as working women who got paid nothing for their production and maintenance of families. Of course, these definitions are now changing, as the meaning of ‘family’ changes, along with profound and parallel changes in the labour market – the entry of women is just one of those – and in attitudes toward sexuality.

When work disappears, the genders produced by the labour market are blurred. When socially necessary labour declines, what we once called women’s work – education, healthcare, service – becomes our basic industry, not a ‘tertiary’ dimension of the measurable economy. The labour of love, caring for one another and learning how to be our brother’s keeper – socially beneficial labour – becomes not merely possible but eminently necessary, and not just within families, where affection is routinely available. No, I mean out there, in the wide, wide world.

Work has also been the American way of producing ‘racial capitalism’, as the historians now call it, by means of slave labour, convict labour, sharecropping, then segregated labour markets – in other words, a ‘free enterprise system’ built on the ruins of black bodies, an economic edifice animated, saturated and determined by racism. There never was a free market in labour in these united states. Like every other market, it was always hedged by lawful, systematic discrimination against black folk. You might even say that this hedged market produced the still-deployed stereotypes of African-American laziness, by excluding black workers from remunerative employment, confining them to the ghettos of the eight-hour day.

And yet, and yet. Though work has often entailed subjugation, obedience and hierarchy (see above), it’s also where many of us, probably most of us, have consistently expressed our deepest human desire, to be free of externally imposed authority or obligation, to be self-sufficient. We have defined ourselves for centuries by what we do, by what we produce.

But by now we must know that this definition of ourselves entails the principle of productivity – from each according to his abilities, to each according to his creation of real value through work – and commits us to the inane idea that we’re worth only as much as the labour market can register, as a price. By now we must also know that this principle plots a certain course to endless growth and its faithful attendant, environmental degradation.

Until now, the principle of productivity has functioned as the reality principle that made the American Dream seem plausible. ‘Work hard, play by the rules, get ahead’, or, ‘You get what you pay for, you make your own way, you rightly receive what you’ve honestly earned’ – such homilies and exhortations used to make sense of the world. At any rate they didn’t sound delusional. By now they do.

Adherence to the principle of productivity therefore threatens public health as well as the planet (actually, these are the same thing). By committing us to what is impossible, it makes for madness. The Nobel Prize-winning economist Angus Deaton said something like this when he explained anomalous mortality rates among white people in the Bible Belt by claiming that they’ve ‘lost the narrative of their lives’ – by suggesting that they’ve lost faith in the American Dream. For them, the work ethic is a death sentence because they can’t live by it.

So the impending end of work raises the most fundamental questions about what it means to be human. To begin with, what purposes could we choose if the job – economic necessity – didn’t consume most of our waking hours and creative energies? What evident yet unknown possibilities would then appear? How would human nature itself change as the ancient, aristocratic privilege of leisure becomes the birthright of human beings as such?

Sigmund Freud insisted that love and work were the essential ingredients of healthy human being. Of course he was right. But can love survive the end of work as the willing partner of the good life? Can we let people get something for nothing and still treat them as our brothers and sisters – as members of a beloved community? Can you imagine the moment when you’ve just met an attractive stranger at a party, or you’re online looking for someone, anyone, but you don’t ask: ‘So, what do you do?’

We won’t have any answers until we acknowledge that work now means everything to us – and that hereafter it can’t.