By Scott Campbell

Source: Institute for Anarchist Studies

Back when I first began selling my labor for a wage in the wasteland of suburbia’s strip malls, I can recall the tedium of stocking shelves, summoning up insincere courtesy in the face of entitled customers and obnoxious bosses, comparing the stacks of money counted at the end of the day with the totals on our paychecks, and feigning adherence to whatever motivational façade management cooked up to mask the reality of our exploitation.

Yet I also remember, much more vividly and fondly, the latent and occasionally eruptive defiance among my co-workers. This included the constant collective complaining about the job, taking more and longer-than-approved breaks, working as little as possible, fudging time sheets, stealing, and the intermittent screaming matches with the boss in the middle of the store. Underpinning all these actions was an unspoken but broadly understood code of silence when it came to such transgressions and, when appropriate, expressions of support for them.

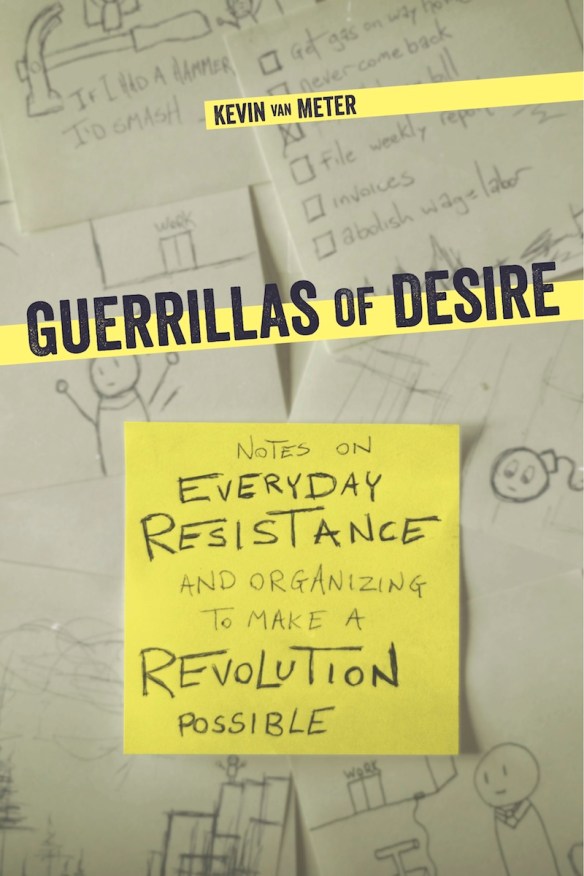

At the time, I didn’t think much about this, it was just how things happened and I’ve encountered similar experiences to varying degrees in every workplace since. Our actions weren’t guided by a political framework nor was there any attempt to organize them in a directed manner. It was more a spontaneous, innate reaction to experiencing the coercion of capitalism. I had cause to reflect upon this anew while reading Kevin Van Meter’s new book, Guerrillas of Desire: Notes on Everyday Resistance and Organizing to Make a Revolution Possible, published by AK Press and the Institute for Anarchist Studies.

In the preface, Van Meter observes that the question motivating him is not “What is to be done?” but “How do people become what they are?” Throughout the course of the book he seeks to provide an answer by locating power in the resistance of workers, apart from any political ideology or organization. Whether and how that inherently anti-capitalist refusal of work develops into revolt or rebellion are the questions he compellingly urges us to reflect and act upon.

To reach that point, Guerrillas of Desire ambitiously takes on multiple tasks that feed into and build on one another. Van Meter initiates a dialogue between anarchism and Autonomist Marxism that leads to a reconceptualization of the working class, bolstered in part by a historical accounting of workplace actions such as the ones I recounted. He labels these “everyday resistance,” committed by “guerrillas of desire,” and proposes a focus on those deeds as the entry point for organizing revolutionary resistance to capitalism. The impetus for this initiative, concisely carried out in under 160 pages, is his proposal that the current approach to organizing is conceptually flawed and therefore destined to fail. “Guerrillas of Desire offers a contentious hypothesis: the fundamental assumption underlying Left and radical organizing, including many strains of anarchism, is wrong. I do not mean organizationally dishonest, ideologically inappropriate, or immoral. I mean empirically incorrect” (13). The incorrect basis for current organizing is the assumption that the poor and working classes are unorganized and passive and that it therefore rests upon activists and organizations to educate and mobilize them for their own sakes. Van Meter instead proposes that there is in fact informal organization and resistance occurring, it is just of a sort that does not fit within the Left’s organizing vision and therefore goes unseen, unrecognized, and unincorporated into political theories, analysis, and action.

To provide a political frame for understanding the “everyday resistance” of the working class, Van Meter draws upon anarchism’s mutual aid – the material and emotional cooperation and reciprocal support that exists in societies – with Autonomist Marxism’s self-valorization – autonomous working class action that counters the state and capitalism, primarily the refusal of work in its myriad forms. Combined together and reinforcing one another, mutual aid and the refusal of work comprise the “everyday resistance” of the working class.

These phenomena also give definition to what is meant by “working class,” which Van Meter defines as “autonomous from both capitalism and the official organization of the Left, broadly including all those who work under capitalism, based in relationships between workers rather than as a structural component of the economy or sociological category” (32). Rather than being premised on income, occupation, or union membership, the working class under Van Meter’s formulation is made up of all those who must perform work under capitalism – be it waged or unwaged, in the factory, home, office, bedroom, affective, or social spheres. However, when they are not taking action in response to their subjugation under capitalism, these people are just workers. They become a class through the process of struggling against the conditions imposed upon them by capitalism. This struggle initially takes the form of everyday resistance based on mutual aid and the refusal of work. It is everyday resistance that unites individual workers as a class because such resistance, even when performed by one person, requires at a bare minimum the tacit complicity of co-workers and preferably their active collaboration.These acts and the social relationships they create and depend on lay the groundwork for the broader and overt organizing against capitalism more commonly interpreted as working class struggle. Using this framework as offered by Van Meter, we can understand the working class as composed of the relationships forged among workers actively in resistance against capitalism.Without anti-capitalist struggle, the working class does not exist.

After laying this theoretical groundwork, the bulk of the book traces the various forms of resistance by slaves, peasants, and workers in the industrial and social factories (the expansion of capitalist logic from the factory into society at large, in particular in service, immaterial, and reproductive work), creating a lineage and legacy of working class resistance against the various formations of capitalism that spans centuries. “Viewing the working class broadly to include slaves and peasants as well as students, homemakers, immigrants, and factory and office workers reveals the breadth of struggle and generalized revolt against work that continues to be imposed” (128). In doing so, Van Meter further builds the framework of the working class as being formed through its self-activity against the demands and deprivations of capitalism.

The historical survey brings the discussion into the present, where Van Meter offers a proposal to address his initial hypothesis that the Left is carrying out its organizing work in an incorrect way. His suggestion is for the organizers of today and in the future to begin their work by “reading the struggles” already underway in the form of everyday resistance. Through investigation and documentation by organizers, new relationships may be fostered with guerillas of desire that allow everyday resistance to expand into larger and more overt forms of autonomous anti-capitalist struggle. He proposes that the seeds of the new, liberatory worlds sought by anarchism and Autonomist Marxism are to be found in the everyday resistances that are already occurring rather than in the latest organizing manual or official Left strategy document..

While impressed after reading through this formulation, I was left with lingering questions. It remained unclear how, for instance, everyday resistance morphed into more overt, organized resistance and the part organizers positioning themselves as readers of struggle played in such a development. The personal anecdotes he provided on stepping back from ideological assumptions and reorienting towards the collective experiences of communities during his work in Long Island were helpful. It brought to mind the story of Marxist-Leninist intellectuals heading off to the Chiapan jungle with grand plans of starting a peasant guerrilla force. Only when they arrived, they found the population had no time or interest in their grandiose ideology. It was only when they dropped their assumptions and worked within the community to understand its needs, concerns and own history of resistance that the Zapatistas emerged. That, however, is a rather specific and exceptional example. I feel Van Meter’s proposal to begin organizing from within everyday resistance based on the notion that it will lead to more overt resistance could benefit from further articulation and direction.

Similarly, the focus on work as existing solely within the capitalist sphere left me curious as to his vision of the place of non-leisure activity under capitalism or even after capitalism. The refusal of the work that maintains capitalism is indispensable. Yet I would not advocate the refusal of work that maintains communal and personal well-being or builds autonomous organization, or writes books reviews in spare time, for example. Certainly, Van Meter would not advocate that either, but it remains a matter necessitating clarification and one that I believe extends beyond an issue of semantics.

Despite those questions, Guerrillas of Desire is aspirational in its scope and contains ideas and proposals worthy of consideration by radicals reflecting on how to engage in the current moment. In a time when mobilizing and organizing around class has fallen off the radar of many, it is a welcome reminder of the importance of paying attention to the working class and the integral role working class struggle plays in resistance to capitalism, alongside the currently more prevalent resistances to capitalist white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, colonization, environmental destruction and more.

Van Meter assists in this advocacy by accessibly presenting an updated Autonomist Marxist perspective of the working class, expanding it, breathing life into, and imbuing it with its own power, separate from both capitalism and the official Left. As such, he allows readers who may toil in a variety of ways under capitalism to see themselves within the working class, conceptualize their activities as part of a broader resistance with a rich history, and inspire them to build on that legacy.

Scott Campbell is a radical writer and translator based in California. He is part of the collectives that publish the websites El Enemigo Común and It’s Going Down. His personal site is fallingintoincandescence.com

Guerrillas of Desire is available here!