The Manifold Crises Threatening Higher Education

By Vince Chernak and Henry A. Giroux

Source: Counterpunch

When Western University president Amit Chakma’s jaw-dropping income was posted recently on the Sunshine list, it put a spotlight on the inequities and conflicts that exist in the contemporary university between the administration and faculty, contract instructors and students. The corporatization of the university means the administrators are well off, while those responsible for actual education, doing the teaching, are struggling to survive.

But that may just be the tip of iceberg in this scandal. Prof. Henry Giroux, a renowned and formative thinker in critical pedagogy notes that the role of the university president has diminished into a fundraising machine and is just part of the disturbing decline in the university. “What we need to do is reimagine that the university is a place to think,” he says, “a place for peace, a place that has something to say about critical thought, about educating people to being engaged citizens. I think the public nature of the university is under siege.”

The McMaster University Professor for Scholarship in the Public Interest is the author of over 60 books, including the recent Zombie Politics and Culture in the Age of Casino Capitalism, Dangerous Thinking in the Age of the New Authoritarianism, Neoliberalism’s War on Higher Education, and The Violence of Organized Forgetting. Giroux discusses how we might retake agency in our universities and in the zombie culture at large.

Vince Chernak: Is it fair to say this situation of discord between administration and faculty is not unique to Western?

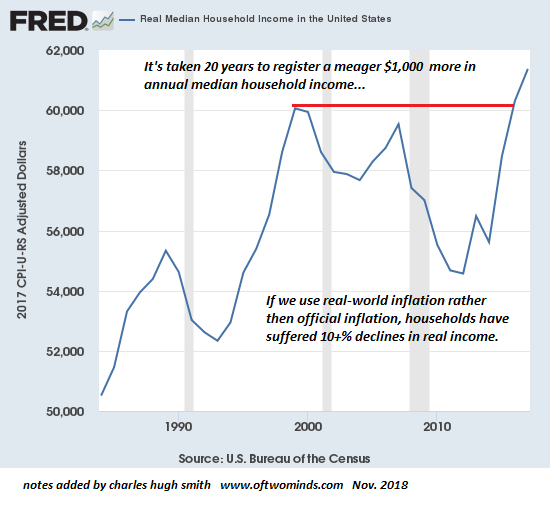

Henry A. Giroux: No, it’s a trend that’s highlighted both in the United States and the United Kingdom, but also increasingly true in Canada. What we basically see is a business model taking over the universities in which power is being concentrated more and more in the hands of administrators and faculty are basically becoming more powerless. I think the real issue here is as Noam Chomsky points out is what you have is a model in which labour costs are being reduced and what’s being increased at the same time is labour servility. I think this increasing casualization of faculty is horrendous in terms of its implications; not only are faculty powerless, their incomes are increasingly being reduced. Now, that’s not as bad in Canada as it is in the U.S. In the U.S. 70 percent of faculty are either part-time or non-tenure track. That’s horrendous. That basically is about the death of the university in my estimation as a critical institution.

So you have a neo-liberal model at work there and increasingly now under the Conservative government in the U.K. that really is destroying education as a public good. It’s no longer seen as a public good, it’s seen as a training centre for corporate interests.

VC: You’ve said 10 years ago that the university president has become a technocratic fund-raising machine. That wouldn’t have been the case a few decades ago?

HG: If you look at the university presidents of the ’60s and ’70s what you see are a number of people who are well known for producing big ideas. People who wrote books about the university, who saw it as a public good. Or at least were struggling with what it meant to maintain it as a public good in an economy that was increasingly coming into the power of financial interests. But I think what we increasingly see now is presidents being reduced to fund raisers. Of course fund raising is important but what you want to see is presidents who have some sense of vision, that can provide a model of what it means to talk about the university in ways that suggest it’s connected to public life, that address important social problems, that it’s a public good, a public trust. This is not what the Harper administration wants from universities, he wants to turn them basically into car factories. I think you have a lot of university presidents in Canada who are caught in the middle of that, who don’t buy that assessment. Certainly not the president of McMaster University. But at the same time I think the pressures are so overwhelming to instrumentalize the university, to turn it into a business culture and at the same time, produce a faculty that’s practically powerless is an ongoing problem that has to be addressed.

VC: It might be that the vociferous outrage here in London isn’t so much about Chakma bringing in a half-million or a million a year in salary, but that his job mostly entails just such fundraising and that he and the board of governors supporting him are out of touch with the real issues on campus. Before a non-confidence vote Chakma even admitted that. But when government support has been in decline, is that such a bad thing—to hire the guy who’s going to bring in revenues? What are the alternatives?

HG: The faculty have to mobilize, along with the students, like they did in the’60s and take the university back. The university is a site of struggle. I think those people who are most affected, the faculty and students, have got to find ways to link up with social movements outside of the university to be able to educate the public, mobilize, do everything they can to say, ‘Look, sorry, the model that we have now defining the university is a model that is not healthy for democracy, and it’s not healthy for students and faculty. Faculty are more than casual labour, students are more than customers and the university is more than simply a training centre for big business.’

We can’t become like Margaret Thatcher, we can’t fall into the argument that there’s no alternative. What we need to do is reimagine that the university is a place to think, a place for peace, a place that has something to say about critical thought, about educating people to being engaged citizens. I think the public nature of the university is under siege.

VC: Faculty and students are agitating to get the board of governors to see that they have lost sight of the purpose of the university. And while Chakma has said he will work diligently to understand the complaints, he recently declined a meeting with the faculty of Media and Information Studies because the faculty allowed media to observe. He’s in damage control mode and his advisors are clearly trying to protect “the brand.” It looks like administration isn’t just suppressing critical and creative thinking from the faculty, they’re almost at war with faculty.

HG: It’s sad to say that when the administrators shut down any possibility for dialogue, when administrations withdraw into cocoon-like gated communities in which they’re always on the defensive, I think that it’s probably not unreasonable to say that this is not just about an assault, this looks like a war strategy. It looks like power is functioning in such a way as to both stamp out dissent and at the same time concentrate itself in ways in which it’s not held accountable.

HG: You’ve noted the branding extends down to the student body: “the school looks like a mall.” The students are branded, and the curriculum is written by corporations. “Where are the public spaces for young people to learn a discourse that’s not commodified?” you ask. “To think about non-commodifiable values like trust, justice, honesty, integrity, caring for others, compassion. There’s no room for the imagination, for creativity.”

VC: That’s an enormously important issue. If the university is going to be a space that takes seriously what it means to educate young people to be critically engaged citizens it can’t construct the university around a set of structures and spaces and organizing principles that seem to suggest the opposite of that — that basically they’re just consumers. The reason that that’s so deadly is that when you instrumentalize and commodify the university like that and you just see students as clients who have to make choices for the marketplace, you’re really talking about the death of a formative culture that is essential for educating people to live in a real democracy. So the issue is not just that branding is becoming an organizing principle of the universities, the real issue is, at what cost? What price is paid for that? What kind of disservice do we do to students? For instance, I was reading today that between 2001 and 2013 the Koch Foundation provided $70 million to 400 campuses — they’re buying faculty, they’re buying courses — in some cases, some of these major corporations have suggested that they’ll give a donation but everyone in the freshman class has to read Atlas Shrugged. What happens when a university is so susceptible that corporate interests step in and decide who is going to be hired, what’s going to be taught? That’s truly the death of the university.

VC: One thing that’s come up under scrutiny through this Western scandal is the prioritizing of STEM (science, technology, engineering, medicine) faculty funding. I believe German post-secondary education may involve such a split between humanities and the technical or professional streams. Do we have an outmoded idea of the university, one that needs a fundamental restructuring?

HG: I think it’s outmoded, entirely. I’ll give you an example. People often talk about health faculties as simply being instrumentalized faculties, professional faculties that are really bogged down in doing practical things. If you look at health faculties today like at McMaster, they’re involved in community work, public services, interdisciplinary work…so I think that when administrators begin to separate these faculties out in ways in which they say things like, ‘Well, the humanities and liberal arts are concerned about things that are non-instrumental, non-functional, we need to diminish their power in the university… the real work is being done by professionals,’ I think that’s a joke and it’s a misrepresentation. The organizing principles in the liberal arts are so entrenched now in the professional faculties that you can’t separate them anymore. It doesn’t make any sense: nuclear scientists are obviously going to have to take in ethical considerations, right? Professional people don’t work in an ethical void. The liberal arts, people can’t simply live in gated communities and write in languages that nobody can understand. There’s going to be a melding, a bleeding into each other in these faculties in ways in which we say, okay, how do we merge questions of public values and professional skills.

But let me go back to your question. You’re right in the sense that increasingly what we see administrations doing are favouring STEM faculties as an excuse to diminish and eliminate the liberal arts and humanities. I’ll give you one example that is unbelievable. In the States you have a governor that’s instituted a policy in which he said that if you take a course that’s in the field of business, that has a direct application to the business world, we will lower your tuition. If you take courses in the liberal arts then you’re going to pay a higher tuition. Can you believe this?

VC: A lot of kids might be avoiding university these days for more practical trade school or college training that’ll lead to employment. Distinguish the value of education versus training.

HG: When I claim that education is simply a form of training I think that what I’m arguing is that you get people sort of educated to learn very specific skills in ways that completely remove from larger socio- political and economic conditions or questions or disciplines, so that people are learning how to be plumbers but they’re not learning about the nature of work and what it means to have meaningful work in a society. I think that when you place the emphasis on simply a kind of instrumental rationality and you refuse to deal with larger questions, conceptual questions about what it means to be well-rounded educationally and what it means to get a general education and what it means to be able to cross disciplines, what it means to learn how to govern and not simply be governed, I think something terrible happens and that distinction is very important. Education is not simply about an immediate fix, i.e., getting a job. Education is about preparing people for life, it’s about preparing people for the future. And I’ll tell you something else, even the rationale that education is training is not good because often the skills people get in five years, those skills are obsolete. Who wants a doctor who can’t think? I mean we don’t want to turn out Joseph Mengele. You want to have people who have some sense of compassion, who understand the world in terms of power relations, who understand that their work is always enmeshed in political relations and relations of power and never can escape from questions of ethical and social responsibility. When we cut that element of education out, I don’t know what you have. You basically have training schools. I don’t want to create mechanics, I want to create people who can think but also can fix your car.

VC: In his book, Shop Class as Soulcraft: an Inquiry into the Value of Work, Matthew Crawford notes that much of work today is mere training in following rote procedures, conceived by a systems engineer and perhaps better done by robots than humans. He argues that there can be more human excellence in working with your hands, in practical work that involves actual thinking and coming up with creative solutions.

HG: John Dewey said the same thing, he said in true experience people learn how to think. Multiple things happen when you have to solve problems and you put things together and you apply them to the real world. We do see a lot of that in the university but I think those economic, political and religious fundamentalists who really see the university as a threat… you know, look, the kind of discussion that we’re having in some ways has to have a historical context and I think that what we often forget is that in the ’60s something happened that blew the lid off the conservative mentality. All of a sudden the ’60s were an era of enormous turbulence, people were struggling over the meaning and the purpose of the university, they were arguing for more ethnic and racial representation, they wanted to broaden courses in what was available in terms of academic disciplines in ways that had something to do with the real world, and all of a sudden the university opened up in a way in which all kinds of people were now coming to the university, in the past they were excluded, ethnic groups, religious groups, minorities.

The right never got over this. I mean they never got over this. That’s why you have the Powell Memo of the 1970s saying that the right has to get together and do something about these cultural apparatuses including schools so that we indoctrinate people for capitalism, we don’t let this happen again. I think that much of what we see all over North America and increasingly in Europe is the legacy of that backlash. This is really a counter-revolution. When you talk about doubling up the salaries, all that, I get it, yeah it’s offensive morally and politically but there’s a larger issue here. When you put the context together what’s happening all over North America you have to say two things, you have to say, one, the university as a site for creating the formative cultures that make a democracy possible is a) under siege, that’s for sure. Democracy is dangerous, and the institutions that produce people who engage in it basically are dangerous. Secondly, neoliberalism as we know it is not just about the governing of the market, it’s about the governing of all social life.

VC: Let’s mention zombies for a bit: zombies are back in a big way in the cultural zeitgeist since at least the beginning of the recession in ’09. You referenced them in Zombie Politics and Culture in the Age of Casino Capitalism. I think originally George Romero cheekily used this metaphor for the numbed conspicuous consumer in the ‘60s and the age of the Cold War threat of nuclear annihilation. Tell us how the zombie is recast in your book in contemporary times.

HG: The zombies suggest two or three things. At one level, zombie becomes a metaphor for talking about the way in which life is being sucked out of a society by a financial elite who really represent the walking dead. They really have produced a death-saturated age, and in that sense the zombies, they’re unthinking, they’re unfeeling, they have no sense of the social and I think in that sense they’re reproducing both an enormous amount of misery and violence in the world and also against the planet itself. Secondly I talk about zombies in ways that suggest a kind of sleeplessness, people basically are so tied to simply surviving that in some ways they have no… time has become an utter deprivation rather than a luxury. They’re so focused on just simply staying alive as opposed to the ’50s and the ’60s when people talked about moving up, that they’ve become zombie-like in the kind of political comas that they find themselves in. They lose all sense of agency, at least a kind of agency that would be individual, collective and engaged towards addressing the world in which they live in. I think we don’t even need to use the word ‘zombie’, we can say this is a population marked by horrible precarity. I mean, we see it in students who are so burdened by debt now that their radical imagination has been eliminated. They’ve become zombies in a sense. They’ve become zombies as victims. And I think ‘zombies as victims’ because it becomes very difficult for them to think about anything else than simply paying back this debt and being able to survive. When you live in a world in which survival of the fittest is the only logic available to you, that’s a form of depoliticization.

VC: One could say we’re living in an age of mass psychopathy, madness. From the short-term thinking of governments, self-serving corporations and down to the wretched individual waiting to win the lottery, we seem to be in a very dark place culturally. Is this a terminal state of the human condition?

HG: No, no, no, it’s not terminal. I mean we see all kinds of movements that basically are fighting against this, and let me just say something about that, it’s an important question. I think first of all you can’t sort of universalize power as only a form of despair. Power is also a form of resistance and I think that what we see all over the world right now, we have seen movements fighting against this kind of neoliberal ‘juggernaut’, we see that with Podemos in Spain, Syriza in Greece, we see it with the Black Lives Matter movement, we see it all over the United States. I think young people are waking up. I’m actually more optimistic than I’ve been in a long time. I think the contradictions of neoliberal capitalism are now so severe, so unbelievable that nobody’s fooled anymore, it’s difficult to be fooled. You know when you don’t have food, you don’t have health care, you don’t have social provisions, people are chipping away at your life to make your life miserable, eliminating the conditions that would enable some sense of security, then it seems to me the space of politics opens up in a way like we haven’t seen before. Now, it doesn’t offer any guarantees, I mean, people could become Nazis, right? They could be like Golden Dawn in Greece, they could join right-wing movements. But I do think that space is opening up, that the alternative media is opening up, I think that a lot of youth movements are now all of a sudden mobilizing in ways to try addressing the most immediate problems they find themselves in, there’s an environmental movement. But the real issue here is not whether we have resistance. There’s resistance. It’s local, it’s invested, it’s serious, but it’s got to be unified. I think from the Occupy movement to the Quebec student movement, what we’ve seen is that these movements tend to fizzle out quickly. They need focus. There’s no long-term organization. The other side of this is that we don’t talk about power enough. There’s an enormous attempt to sort of talk about leaderless revolutions. I’ll be honest, I don’t know what that means. I don’t know what it means to claim that everybody is empowered, that we don’t need organizations to sort of address the issues that we find ourselves in. We’ve got to rethink something about horizontal power, to seize it in ways that suggest that power has to be seized. You have to fight for it. Do you really believe these ruling classes are going to sort of just step down? And that’s not a call for violence; that’s a call for non-violence. That’s a call for street actions, for mobilizations, people developing third parties, trying to imagine political systems outside of the traditional liberal notion of capitalism. Liberalism is dead. It’s dead. It’s simply a center-right movement now. It’s all about accommodation with Obama being the ultimate spectacle of that accommodation. And so the time does exist for reinventing the very meaning of politics and what that might mean.

VC: Do you think the digital revolution we’re going through is aiding that process?

HG: I think it has enormous potential, I really do. I think it has an enormous amount of potential. I think it has to be seized. I mean right now that revolution is in the hands of both the surveillance industry and people who in fact are wedded to privatization, putting everything up on the web, from if you wiped your baby today to when you went to the movies last night. I think that what people have to realize is that that site itself is not about entertainment, it’s not just about happiness, it’s not about instant pleasure, it’s also a site of struggle and that we know the cultural apparatuses that dominate neoliberal societies are really in the hands of financial elites. We need to educate a generation of young people who are not just cultural critics but are also cultural producers. They have to learn these technologies. They have to learn to create their own radio stations, they have to learn how to do alternative media, they have to learn how to open up alternative sites. I look at sites like TruthDig and TruthOut and Counterpunch. These sites are growing like you can’t imagine because there are very few sites that are offering up the kind of alternative languages and modes of understanding that young people really need. They need a new language. The alternative media offers enormous possibilities for that.

VC: You gave a talk at Fanshawe College last year, “A World Beyond Violence in Media.”

HG: What I was trying to say is that we need to really reclaim the radical imagination, we need to rethink the world in terms that don’t simply define it through exchange values, through privatization, commodification, deregulation. We need to invent new modes of solidarity, we need to reclaim public values, public trust, we need to reclaim a sense of the common good and we need to do it globally. We need a new understanding of politics, one that refuses to equate capitalism with democracy. I think that one of the great changes that marks the 21st century is that power is global and politics is local. The global elite, they’re not indebted to anybody, they don’t believe in political concessions anymore because they float. They’re not tied to nation states, and I think there’s an enormous need to really rethink democracy in global terms and not just simply local terms, that’s not going to work. And I think one of the greatest things we’re beginning to see is, if you look at the movements that are now developing against police brutality, I mean these kids are talking to people in Mexico, they’re talking to youth groups in France. What the internet has opened up is the possibility for creating global alliances and I think that that matters. The real crisis that we face is not simply about the crisis of economics, it’s about the crisis of ideas. The crisis of ideas does not match the crisis of economics. And I think that’s an educational and pedagogical issue. We need to make education central to politics. Central. And I don’t just simply mean that we need to recognize that education takes place outside of the schools, I think it means that we need to build those kind of sites, those kind of cultural apparatuses in which education is crucial in which it mobilizes people, it educates people, and it offers a sense of alternative and a space for agency that we haven’t seen before.

VC: You have a new book, Dangerous Thinking in the Age of the New Authoritarianism. There’s a quote, “There are no dangerous thoughts. Thinking itself is dangerous.”

HG: t comes from Hannah Arendt. One of the things that Arendt said that I love is, she said at the base of fascism was a kind of thoughtlessness. An inability to think. An inability to understand the world in terms that related different issues, that brought things together. I think what we have to recognize is, thinking is not simply a by-product of actions, it has to inform action, and thinking has to be central to how we talk about a whole range of things from education to a number of public spheres. Thinking is so crucial in that once you eliminate it or you place it under siege or you repress dissent, then what you do is you create the foundation for a kind of authoritarianism in which thinking is seen as dangerous. And I think we’re increasingly seeing that. I think that thinking is dangerous in many places, not only in the most authoritarian states like Iran and others that we can mention but increasingly in the West. When you have a Harper government that wants to censor what scientists are saying about climate change, who are criticizing it and saying it’s man-made, that’s thinking that’s dangerous. You have in the United States the head of the Senate committee on the environment who says that only God can change the environment — believe me, that’s not just an argument for religious fundamentalism, that’s an argument against critical thinking itself.

A Shorter Version of this interview appeared in the London Yodeller.

Vince Chernak writes for the London Yodeller.

Henry A. Giroux currently holds the McMaster University Chair for Scholarship in the Public Interest in the English and Cultural Studies Department and a Distinguished Visiting Professorship at Ryerson University. His most recent books are America’s Education Deficit and the War on Youth (Monthly Review Press, 2013) and Neoliberalism’s War on Higher Education (Haymarket Press, 2014). His web site is www.henryagiroux.com.