By Steven Stoll

Source: Orion Magazine

A chainlink fence topped with razor wire surrounds fourteen acres of thistle and grass at East Forty-First Street between Long Beach Avenue and South Alameda Street in Los Angeles. These two city blocks occupy a transitional environment of sorts. In one direction the sight of small houses stretches for miles toward the Pacific Ocean, but turn around and the neighborhood becomes industrial, consisting of a textile factory, a scrap metal recycling company, trucking terminals, and warehouses. The tracks of the Southern Pacific Railroad run parallel to Long Beach Avenue. There are few trees or anything green and growing but the drought-resistant thistle.

In 1986, the City of Los Angeles acquired the land from a group of owners through eminent domain, but then folded plans to build a waste incinerator when the community resisted. The land ended up in the holdings of the Harbor Department. It had been two years since the uprising that followed the acquittal of four Los Angeles police officers, tried for beating Rodney King. Perhaps looking to make a gesture and lacking its own use for the site, the Harbor Department invited members of a local food bank to plant a community garden.

They did. Between 1994 and 2006 hundreds of families grew a profusion of food plants on what had been a blighted lot just a few years before. One visitor identified a hundred species, most of them native to Mexico and South America— chayote, guava, tomatillo, sapodilla, and sugarcane, in addition to maize, beans, avocados, bananas, and squashes. The South Central Farm was not misnamed: photographs show the land in robust cultivation, producing a wealth of food.

But in 2001, one of the prior owners filed a lawsuit against the city. The property had never been used to build the incinerator, and so, he argued, Los Angeles had no reason to seize it. The city settled the case in 2003 by selling the fourteen acres back to the prior owner.

In the ensuing confrontation a single absentee negated the sustained labor and improvements of 350 families, representing around a thousand people, now accused of squatting. They refused to leave. Lawyers filed briefs. Gardeners swore resistance. (One said, “Just think if we assemble, two from every family, and you know we’ll each grab a hoe, and no one will get past us.”) Movie stars showed up with camera crews. A foundation offered millions of dollars as a purchase price, which the owner rejected. A date was set for the forced removal of the stalwarts. On June 13, 2006, Los Angeles County Sheriffs arrested forty people. Bulldozers destroyed the farm. A decade later, the land remains vacant.

In the case of the South Central Farm, ownership for profit triumphed over use for subsistence, which, of course, is the way of the world. Nothing could be more ordinary than a landowner asserting his rights. And yet, just five centuries ago, what happened on those fourteen acres in south Los Angeles wouldn’t have made sense to anyone.

In 1500, no one sold land because no one owned it. People in the past did, however, claim and control territory in a variety of ways. Groups of hunters and later villages of herders or farmers found means of taking what they needed while leaving the larger landscape for others to glean from. They certainly fought over the richest hunting grounds and most fertile valleys, but they justified their right by their active use. In other words, they asserted rights of appropriation. We appropriate all the time. We conquer parking spaces at the grocery store, for example, and hold them until we are ready to give them up. The parking spaces do not become ours to keep; the basis of our right to occupy them is that we occupy them. Only until very recently, humans inhabited the niches and environments of Earth somewhat like parking spaces.

Ownership is different from appropriation. It confers exclusive rights derived from and enforced by the state. These rights do not come from active use or occupancy. Property owners can neglect land for years, waiting for the best time to sell it, even if others would put it to better use. And in the absence of laws protecting landscapes, the holders of legal title can mow down a rainforest or drain a wetland without regard to social and ecological cost. Not all owners are destructive or irresponsible, but the imperative to seek maximum profit is built into the assumptions within private property. Land that costs money must make money.

Champions of capitalism don’t see private property as a social practice with a history but as a universal desire—a nearly physical law—that amounts to the very expression of freedom. The economist Friedrich Hayek called it “the most important guarantee of freedom, not only for those who own property, but scarcely less for those who do not.” But Hayek never explained how buyers and sellers of real estate spread a blanket of liberty over their tenants. And he never mentioned the fact that the concept, far from being natural law, was created by nation-states—the notion that someone could claim a bit of the planet all to himself is relatively new.

Every social system falls into contradictions, opposing or inconsistent aspects within its assumptions that have no clear resolution. These can be managed or put off, but some of them are serious enough to undermine the entire system. In the case of private property, there are at least two—and they may throw the very essence of capitalism into illegitimacy.

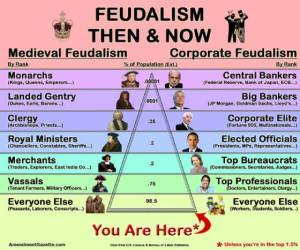

The first of the system’s contradictions points to its origins. Land in the English countryside during the sixteenth century was regulated by feudal obligations so obscure and so thick that few people today can make sense of them. An English peasant could use a run of soil for a term of years or for her entire life, but it did not belong to her. Village elders, representatives of the local lord, and even the deacon of the church might have claimed an interest in how this or that field was planted. Everyone from monarch to serf received a different slice of the realm. These use rights could be exchanged only in very limited ways: a lord occupied his ancestral house and manor for as long as he lived, but he could not sell them.

All sorts of events caused the demise of feudalism. The Black Death of the fourteenth century killed so many millions that the labor market tipped in favor of those who survived. The spread of money gave things exchange value and made buying and selling easier. Food production increased during the sixteenth century, creating more calories for work and more commodities for trade. And an international wool market inspired lords to change common fields into sheep walks.

The problem was that lords could not put sheep where they wanted. They lived within the feudal assemblage of obligations and rights attached to social orders and scraps of landscape. Faced with declining returns and proliferating opportunities, they began to curse the old rules—they wanted land for themselves.

Enclosure is just what it sounds like: the physical and legal bounding of an area. In practice it meant the seizure of villages, common fields, and outlying forests and marshes. It allowed lords to evict former residents so that they could do new things with land. Sometimes it happened by agreement, with peasants giving in to demands they feared to contest; other times there was violence. In 1607 at least one thousand peasants tore up hedges in Northamptonshire and filled in ditches that demarcated property lines. The rebels made a statement: “Wee, as members of the whole, doe feele the smarte of these incroaching Tirants, which would grind our flesh upon the whetstone of poverty.” King James didn’t flinch from the whetstone. His forces killed forty insurgents and hanged their leader.

The king’s involvement tells us that grasping lords did not do this dirty work by themselves. Parliament legalized their land grab by granting them something that had never before existed in human history: ownership. Lords could now act without regard to tradition or the needs of residents. Some demolished whole communities. The word pauper dates from the seventeenth century to describe poor people who wandered the roads homeless, eating anything they could scavenge and turning up cold and wet at church doors. Peasants became workers as their only option for survival. Some stooped for a wage on the very land they once tilled as members of villages.

Enclosure created two things at once: private property and wage labor, the essential preconditions for capitalism. Like all social practices, private property has a degree of flexibility. Some of its advantages can and should be diffused among as many people as possible. By eliminating messy titles to land and its embeddedness in tradition, enclosure made possible a new measure of innovation and abundance. But that’s also the first of its contradictions. It generates wealth and unprecedented social power for some by making others poor and dependent.

All of this matters because enclosure never came to an end. It jumped continents and kept on going. The colonial wars for North America, in which Britain and then the United States seized land from hundreds of tribes, can be understood as a rolling dispossession—by purchase, treaty, and ejectment. Enclosure also took place in Australia and South Africa. Wherever nation-states became landowners they turned the commons into private property. The epicenter of enclosure today is Africa. A resident of the village of Dialakoroba, in Mali, which has lost thousands of acres to foreign investors, recently said this: “I do not know, in ten to twenty years, how people will live in our villages because there will be no land to till. . . . Everything has been sold to rich people in very opaque conditions.”

Private property’s second contradiction comes from the odd notion that land is a commodity, which is anything produced by human labor and intended for exchange. Land violates the first category, but what about the second? As the historian Karl Polanyi wrote, land is just another name for nature. It’s the essence of human survival. To regard it as an item for exchange “means to subordinate the substance of society itself to the laws of the market.”

Clearly, though, we regard land as a commodity and this seems natural to us. Yet it represents an astonishing revolution in human perception. Real estate is a legal abstraction that we project over ecological space. It allows us to pretend that a thousand acres for sale off some freeway is not part of the breathing, slithering lattice of nonhuman stakeholders. Extending the surveyor’s grid over North America transformed mountain hollows and desert valleys into exchangeable units that became farms, factories, and suburbs. The grid has entered our brains, too: thinking, dealing, and making a living on real estate habituates us to seeing the biosphere as little more than a series of opportunities for moneymaking. Private property isn’t just a legal idea; it’s the basis of a social system that constructs environments and identities in its image.

Advocates of private property usually fail to point out all the ways it does not serve the greater good. Adam Smith famously believed that self-interested market exchange improves everything, but he really offered little more than that hope. He could not have imagined mountains bulldozed and dumped into creeks. He could not have imagined Camden, New Jersey, and other urban sacrifice zones, established by corporations and then abandoned by them. Maximum profit is the singular, monolithic interest at the heart of private property. Only the public can represent all the other human and nonhuman interests.

Unbelievably, perhaps, the United States Congress has done this. Consider one of its greatest achievements: the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973. The act nails the abstraction of real estate to the ground. When a conglomerate of California developers proposed a phalanx of suburbs across part of the Central Valley, they came face to face with their nemesis: the vernal pool fairy shrimp. In 2002, the Supreme Court upheld the shrimp’s status as endangered and blocked construction. It was a case in which the ESA diminished the sacred rights to property for the sake of tiny invertebrates, leaving critics of the law dumbfounded. But those who would repeal the ESA (and all the other environmental legislation of the 1970s) don’t appreciate the contradiction it helps a little to contain: the compulsion to derive endless wealth from a muddy, mossy planet.

Of course, in the era of climate change, those invaluable laws and the agencies they created now seem too limited in their scope and powers to take on the spectacular collision between Economy and Ecology now in motion. But maybe the most radical way we can treat the ownership of Earth—the single most subversive notion we can have about private property—is that it’s merely a social relationship, an agreement between people to behave in certain ways. It can be challenged, changed, and contained. Much of what holds failing social systems together is that those in power succeed in eliminating the mere thought that things could be otherwise.

Should private property itself be extinguished? It’s a legitimate question, but there is no clear pathway to a system that would take its place, which could amount to some kind of global commons. Instead I suggest land reform, not the extinguishing of property rights but their radical diffusion. Imagine a space in which people own small homes and gardens but share a larger area of fields and woods. Let’s call such legislation the American Commons Communities Act or the Agrarian Economy Act. A policy of this sort might offer education in sustainable agriculture keyed to acquiring a workable farm in a rural or urban landscape. The United States would further invest in any infrastructure necessary to move crops to markets.

Let’s give abandoned buildings, storefronts, and warehouses to those who would establish communities for the homeless. According to one estimate, there are ten vacant homes for every homeless person. Squatting in unused buildings carries certain social benefits that should be recognized. It prevents the homeless from seeking out the suburban fringe, far from transportation and jobs (though it’s no substitute for dignified public housing). Plenty of people are now planting seeds in derelict city lots. In Los Angeles, an activist named Ron Finley looks for weedy ground anywhere he can find it for what he calls “gangsta gardening,” often challenging absentee owners. In 2013, the California legislature responded to sustained pressure from urban gardeners like Finley and passed the Urban Agriculture Incentive Zones Act, which gives tax breaks to any owner who allows vacant land to be used for “sustainable urban farm enterprise.”

Squatting raises another, much larger question. To what extent should improvements to land qualify one for property rights? The suppression of traditional privileges of appropriation amounts to one of the most revolutionary changes in the last five hundred years. All through the centuries people who worked land they did not own (like squatters and slaves) insisted that their toil granted them title. The United States once endorsed this view. The Homestead Act of 1862 granted 160 acres to any farmer who improved it for five years. Western squatters’ clubs and local preemption laws also endorsed the idea that labor in the earth conferred ownership.

It’s worth remembering that there is nothing about private property that says it must be for private use. Conservation land trusts own vast areas as nonprofit corporations and invite the public to hike and bike. It’s not an erosion of the institution of property but an ingenious reversal of its beneficiaries. But don’t wait for a land trust to be established before you enjoy the fenced up beaches or forests near where you live. Declare the absentee owners trustees of the public good and trespass at will. As long as the land in question is not someone’s home or place of business, signs that say KEEP OUT can, in my view, be morally and ethically ignored. Cross over these boundaries while humming “This Land Is Your Land.” Pick wildflowers, watch sand crabs in the surf, linger on your estate. Violating absentee ownership is a long-held and honorable tradition.

The arrest of the South Central Farmers was deeply disturbing in Los Angeles. So much so that citizens began to call for other farms, in other locations throughout the city and county. Ten years later community gardens abound. More than a hundred of them are thriving, including the Stanford Avalon Community Garden, which was established by some of the very families evicted from the South Central Farm. It runs one mile long and 80 feet wide underneath power lines, on city property. There is space for 180 plots, each about 1,300 square feet. The farmers compete with each other for the greatest yields. They pay a small fee for a plot and absorb all the food into their households, to be eaten and sold.

Building this garden movement has not extinguished any of the rights of private or public landowners. But only sustained resistance and protest could have forced these entities to accommodate thousands of household farmers. Yet nothing could be more ordinary or more radical than the desire for autonomy from the tyranny of wages, a dream that persists in billions of humans striving in slums and factories, ready for their moment to reclaim the commons.

Steven Stoll is Professor of History at Fordham University, where he teaches environmental history and the history of capitalism and agrarian societies. He is the author of Larding the Lean Earth: Soil and Society in Nineteenth-Century America (2002) and The Great Delusion (2008), about the origins of economic growth in utopian science. His writing has appeared in Harper’s Magazine, Lapham’s Quarterly, and the New Haven Review. He is finishing a book about losing land and livelihood in Appalachia.