By Lisa Fazio

Source: Resilience

Hierarchy

Power structures establish various systems to ensure the organisation of interrelationships and the distribution of resources throughout a group, community, or ecosystem. In human terms, these systems become our tribes, societies, and civilisations. The dominant power structure in the Western world at this time is capitalist, colonial, and hierarchical, with resources being distributed (or, more accurately, hoarded) from the top down.

Before capitalism, many of us who have descended from the nations of Europe have a cultural history of feudalism or some other social-ranking hierarchy. Feudal society is the rootstock of capitalism. One of the primary differences subsumed from this medieval power structure by early capitalism was the waged exchange of labour. The feudal peasants were non-waged, that is, not paid in monetary currency for their labour. Instead, they were paid by an exchange of resources such as land, shelter, and farming rights. Both capitalist and feudal hierarchies were architected to direct and control the circulation of currency from those at the top, who are the elite and few, down to those at the bottom, who are the poor and many.

Capitalism depends on unrestrained growth and production, the manufacturing of material goods, and the extraction of resources to meet these ends. Colonisation, the imperious expansion of geographic, cultural, and political boundaries becomes requisite — with all its cruelty and overconsumption — as a result of this excessive and continuous reach to sustain the unsustainable.

When contemplating the quagmire of obstacles and institutions within our capitalist society that interfere with the equitable and just interchange of currency and access to resources, I find myself motivated to explore less oppressive economic, social, and political human relationships.

In doing so, I have become aligned with that ever-gallant and hopeful group of folks dismissed as unrealistic dreamers. We ‘dreamers’ always hold fast to the truth that the wilful designation of creation and power can be delineated into a network of horizontal or lateral functions that make greed, conquest, and competition unnecessary and invalid, except in extreme conditions.

In the words of Larry Wall, creator of Perl, the open-sourced computer programming language: ‘There is more than one way to do it.’ Perl, and Wall’s band of merry hackers, revolutionised the internet with a coding script that encourages other programmers to interject or hack, as they say in the business, their own design style and innovations that contribute to improvements and success for everyone using the network.¹ These internet wizards built the bridge between those of us who simply want to use the internet and those who actually understand it.

I personally am not remotely skilled in the exotic language of programming or the strange tongue of capitalist economics. As one called to the path along the hedges, in the woods, the fields, the gardens, and all the green, untamed and untrailed places, I have found another way to do things in learning the ways of the world beneath the dark shadows of treetops and in the soils with the rooted ones.

As a folk herbalist practising in the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains of New York State, I live remotely, keeping a distant participation to some degree (perhaps never enough?), in the mainstream rush and panic of daily life in the ‘real’ world of productivity, competition and corporate time sheets. My work with others, however, brings me into direct contact with the consequent ills, both physical and emotional, of life within the overworked, overstimulated and ‘red in tooth and claw’ system. My long hours and days gathering and growing the herbs to share with my clients, family, neighbours and friends feels like a different world or alternate reality in contrast to the interface I must make with the civilised world of offices, fluorescent lights and concrete. While I truly love all parts of my work, this polar interchange always clearly elucidates for me the distinct difference between the world of unruly winds and wild waters, and the tame and burning filaments of electricity enslaved within the lightbulb.

Much of my herbal work is spent with a shovel, basket and clippers as I dig and gather roots, leaves, flowers, bark and berries that are prepared into teas and other herbal formulations. I make every practical effort to harvest from local sources. This requires me to be tuned into to the seasonal cycles and growing patterns of wild plants. I also grow a variety of herbs in my own garden, and have become acutely tuned into conservation and ethical harvesting techniques that ensure the long-term survival and proliferation of our wild medicine plants.

This art and practice of traditional herbalism has deep roots into the history of every culture on earth. These roots have twisted, turned and intertwined throughout thousands of years of human civilisation, often being lost and forgotten as the quality of our communal engagements and our narrative with the world has placed humans on top of a hierarchy that centralises power into an above-ground, rootless, disembodied, hegemony.

That said, I think it’s important here to acknowledge that hierarchies occur naturally in wild communities, especially in herd animals, and that hierarchy is not always played out as an oppressive power structure. It can be an excellent tool for ensuring survival, protection and the health of a herd or community when based on consensus, synergy and cooperative principles.

Becoming radicle

Radicle: a rootlike subdivision, the portion of the embryo that gives rise to the root system of the plant

— biology-online.org

Radicle describes the first part of the seed to emerge after germination that subsequently becomes the primary root. Radicles and the roots they become are a most powerful natural force that, as every city sidewalk knows, will crack and divide concrete. The soil depends upon these mighty revolutionaries to deeply move, turn and aerate the surface of the planet so that life can ascend from it. Plants ‘know’ that in order for productive growth to be sustained, they must first set their roots and begin to make contact with the vast and nutritious field of minerals and essential microbes within the substratum.

Plant roots have many different and effective growing styles, but my favourite are those that are rhizomatic. A rhizome is actually an underground stem that is rootlike; it spreads horizontally, sending out shoots and creating a lateral chain of connection where new sprouts can emerge.

Rhizomes are non-hierarchical and extremely resilient because even if you dig up one part, the other sections will continue to grow and proliferate. Rhizomes have no top or bottom, any point can be connected to any other. They can be broken off at any point and will always be able to start up again. Their network can be entered at any point; there is no central origin. And because there is no central regulatory force, rhizomes function as open systems where connections can emerge regardless of similarities or differences. Freedom of expression exists within a rhizome.

Rhizomes, therefore, are heterogeneous and can create multiplicities, or many different roots, that are sovereign but still in contact and communication with all other parts of the system. This is in contrast to, for instance, a tree, which has a central origin or trunk from which all of its roots and branches emerge. Disconnected from that source, they are no longer in direct contact with their growing system.

As author and storyteller Martin Shaw writes about ‘the rhizomatic universe’ in his book A Branch From the Lightening Tree:

The rhizome is a plant root system that grows by accretion rather than by separate or oppositional means. There is no defined center to its structure, and it doesn’t relate to any generative model. Each part remains in contact with the other by way of roots that become shoots and underground stems. We see that the rhizome is de-territorial, that it stands apart from the tree structure that fixes an order, based on radiancy and binary opposition.

Learning methods and cultural philosophies have been inspired and developed from the patterns observed within rhizomatic root systems. One such concept was introduced by philosopher Guilles Deleuze and psychoanalyst Felix Guattari. From their book on the subject, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia:

As a model for culture, the rhizome resists the organizational structure of the root-tree system, which charts causality along chronological lines and looks for the original source of ‘things’ and looks towards the pinnacle or conclusion of those ‘things.’ A rhizome, on the other hand, is characterized by ‘ceaselessly established connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences, and social struggles.’ Rather than narrativize history and culture, the rhizome presents history and culture as a map or wide array of attractions and influences with no specific origin or genesis, for a ‘rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo.’ The planar movement of the rhizome resists chronology and organization, instead favoring a nomadic system of growth and propagation.

In this model, culture spreads like the surface of a body of water, spreading towards available spaces or trickling downwards towards new spaces through fissures and gaps, eroding what is in its way. The surface can be interrupted and moved, but these disturbances leave no trace, as the water is charged with pressure and potential to always seek its equilibrium, and thereby establish smooth space.

Examples of rhizomatic patterns exist throughout the living world and include plants such as ginger, crabgrass, violets and, my favourite, wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicalis). In human terms we can see many examples of rhizomatic systems, such as we discussed above about Larry Wall and the internet, even amid the context of complex societal hierarchy. New economic and environmental models of power such as permaculture, bioregionalism, and re-localisation are designed to work as horizontal, cooperative, synergistic, and non-competitive systems.

The Rhizomati

Rhizome: A continuously growing horizontal underground stem that puts out lateral shoots and adventitious roots at intervals.

— Oxford English Dictionary online

Herbal medicines are, and always have been, a rhizomatic source of the equitable and lateral distribution of basic needs that seeks not to hoard, commercialise, and capitalise on healthcare or to dole it out only to those with access to the necessary currency. Herbs themselves have not escaped the thralls of patriarchal conquest. All of our modern medicine was founded on the insight gained from the common people and their unwritten relationship with the medicine of the plants. Many of the early European physicians gathered their knowledge from village herbalists, often women who could not read or write (as the patriarchy forbade them). These women are rarely even mentioned in the published literature of medical history. An example can be found in the book written by Dr William Withering (1774-1799), the man who is said to have ‘discovered’ the medicinal use of foxglove. The very first page of his book makes a short mention of a village wise woman who used it in a formula for dropsy: ‘I was told that it had been a long-kept secret by an old woman in Shropshire, who had sometimes made cures after the more regular practitioners had failed.’

The village healers were not elite or favoured by the ruling classes, and in fact were historically perceived as a threat. Their healing work was focused on the direct and intimate needs of their local community, which they frequently sought to empower and support. Traditional herbal medicine was not motivated by profit nor was it sanctioned by the overculture.

In our current times, herbal medicine and plant-based culture has re-emerged in many forms and I perceive it is in a major cycle of transformation. Many call it the ‘herbal renaissance’ and it’s not clear yet what the trajectory will be, as the world seemingly changes at the speed of light. However, the core values remain inextricably connected to the interdependent place-based character of the village healer and his or her reciprocal conversation with the wild and green world.

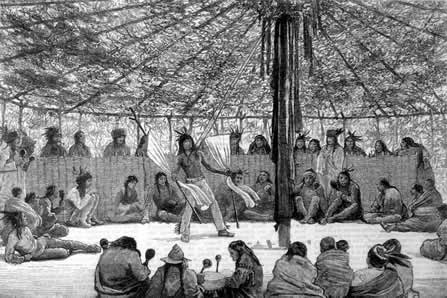

Our ancestors in healing, the long-ago plant people, were in service to their human community as well as the medicine allies they harvested from the hedges. These plant people often lived on the edge of town and worked as not only healers of physical sickness, but also practitioners of spirit, shamans of the village soul, and knowers of, or in old English ‘cunners’ of, the ‘wort’, or herb. Some were called wortcunners. Some were called magicians. Some were called witches. There are many different types of herbalists now and in the past. In ancient times — interestingly! — they were called the rhizomati, or by some sources, rhizotomoki, meaning ‘root gatherers’ or ‘root cutters’.

The rhizomati were rhizomatic practitioners of underground and lateral energy patternsas found in the plant kingdom. According to Christian Rätsch, ‘the rhizotomoki still spoke with the plant spirits…’ He adds: ‘These root-gatherers observed the gods sacred to the respective plant. They made use of the moon’s energy and knew the particular oath formulas for each plant. Witchcraft medicine belongs to the spiritual and cultural legacy of the rhizotomoki.’

Rätsch asserts, therefore, that ‘witchcraft medicine is wild medicine. It is uncontrollable, it surpasses the ruling order, it is anarchy. It belongs to the wilderness.’² Anarchy and wildness, in this sense, are not instances of chaos, mayhem, or lack of a system; rather, it is a system that is self-organised, organic, self-regulated, and impervious to oppressive external control mechanisms.

The rhizomati were carriers of traditional healing knowledge and have emerged at various points in time. In fact, as would a rhizome — going underground for a time andsprouting their legacy up to the surface in another place or time. Renowned modern-day herbalist David Hoffman has compared herbalists of our time to the Greek ‘rhizotomoi’ who held a very special place in the hierarchy of health-care practitioners during ancient times. He asserts that, now as then, herbal healers ‘breach so many realms.’

It is important to understand that the rhizotomoi were not merely the garden labourers that grew the plants, nor did they have the status of academic physicians who dispensed already prepared pills and formulas. Hoffman says: ‘They were people who knew the plants, knew where they grew, knew how to cultivate them, knew how to collect them appropriately, knew how to make the medicine, but then also knew how to use the medicine in the context of the people’s needs… they were herbalists.’

The legacy of these herbalists has carried their medicine bags into the vernacular, or kitchen, gardens of the past few hundred years in Europe and North America. Such gardens belonged to people of any class, and provided subsistence food and medicine to individuals and families. These communal plots were stewarded by the rhizomati and provided a local source of plants and seeds, were designed to meet the natural rhythms of the seasons, and were small enough to adapt to changing local conditions. They were places ‘in which “herb women” and rhizomati, root gatherers, are a key source of plant materials and seeds, and garden innovations are shared among peers—family, neighbors, friends—rather than distributed by a central authority.’³

Today’s root cutters, root gatherers, folk herbalists, plant charmers, and the like, face unknown challenges as the trail leads into the future of a global, capitalist economy. Herbal medicine has become increasingly mainstream and, will no doubt, continue to be commodified and profiteered at some level.

The overculture has made many recent bids to commercialise, exploit and restrict the use of plants by the people. There have been recent regulations enacted that limit the ability of herbalists to maintain home-based businesses, thereby restricting access to local products and serving the burgeoning corporate herbal industry.4

That is not to say that there is not a place in our health-care system for phyto-physicians that work with herbs allopathically. Plant-based preparations have already found a place in mainstream bio-medicine as a complementary modality, a method of prevention, and as a tool of synergy to potentise pharmaceutical protocols. However, this does not concede the necessity of the decentralised, community focused, and client-centred practice of folk herbalists. The modern rhizomati are a source of resilience and empowerment for our society and world, thanks to their interface with plants and people. This resilience will come not only at our resistance to capitalist exploits, but in our ability to establish rhizomatic, horizontal and local systems of vital sustenance, imagination, and community.

Change and dissent are enacted on even the simplest, most humane level when we just become aware of equitable alternatives to our dominant power structure. This I believe to be true well beyond the realms of herbal medicine practice. It has implications for our homes, businesses, communities local and beyond, schools, food production, the arts, and developing technologies. The key to the door of social justice and change is the knowledge that there are other ways to do it — as well as in the courage and innovation of those that are willing to imagine more than one possibility.

May the rhizomati live again and may we all rise rooted!

—

Footnotes

1. Silberman, Steve, Neurotribes, New York: Avery, 2015

2. Müller-Ebeling, Claudia, Christian Rätsch, and Wolf-Dieter Storl, Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants, Rochester, Vermont Inner Traditions, 2003

3. ‘Vernacular Gardens’, Wyrtig.com, For gardeners with a sense of history, 2015. Accessed February 18, 2017

4. For more on these regulations or the cGMP laws: A Radicle blogspot. FDA cGMP compliance open source project. aradicle.blogspot.com, 2015. Accessed February 18, 2017