By John & Nisha Whitehead

Source: The Rutherford Institute

“There are no dangerous thoughts; thinking itself is a dangerous activity.”—Hannah Arendt

Get ready for the next phase of the government’s war on thought crimes: mental health round-ups and involuntary detentions.

Under the guise of public health and safety, the government could use mental health care as a pretext for targeting and locking up dissidents, activists and anyone unfortunate enough to be placed on a government watch list.

If we don’t nip this in the bud, and soon, this will become yet another pretext by which government officials can violate the First and Fourth Amendments at will.

This is how it begins.

In communities across the nation, police are being empowered to forcibly detain individuals they believe might be mentally ill, based solely on their own judgment, even if those individuals pose no danger to others.

In New York City, for example, you could find yourself forcibly hospitalized for suspected mental illness if you carry “firmly held beliefs not congruent with cultural ideas,” exhibit a “willingness to engage in meaningful discussion,” have “excessive fears of specific stimuli,” or refuse “voluntary treatment recommendations.”

While these programs are ostensibly aimed at getting the homeless off the streets, when combined with advances in mass surveillance technologies, artificial intelligence-powered programs that can track people by their biometrics and behavior, mental health sensor data (tracked by wearable data and monitored by government agencies such as HARPA), threat assessments, behavioral sensing warnings, precrime initiatives, red flag gun laws, and mental health first-aid programs aimed at training gatekeepers to identify who might pose a threat to public safety, they could well signal a tipping point in the government’s efforts to penalize those engaging in so-called “thought crimes.”

As the AP reports, federal officials are already looking into how to add “‘identifiable patient data,’ such as mental health, substance use and behavioral health information from group homes, shelters, jails, detox facilities and schools,” to its surveillance toolkit.

Make no mistake: these are the building blocks for an American gulag no less sinister than that of the gulags of the Cold War-era Soviet Union.

The word “gulag” refers to a labor or concentration camp where prisoners (oftentimes political prisoners or so-called “enemies of the state,” real or imagined) were imprisoned as punishment for their crimes against the state.

The gulag, according to historian Anne Applebaum, used as a form of “administrative exile—which required no trial and no sentencing procedure—was an ideal punishment not only for troublemakers as such, but also for political opponents of the regime.”

Totalitarian regimes such as the Soviet Union also declared dissidents mentally ill and consigned political prisoners to prisons disguised as psychiatric hospitals, where they could be isolated from the rest of society, their ideas discredited, and subjected to electric shocks, drugs and various medical procedures to break them physically and mentally.

In addition to declaring political dissidents mentally unsound, government officials in the Cold War-era Soviet Union also made use of an administrative process for dealing with individuals who were considered a bad influence on others or troublemakers. Author George Kennan describes a process in which:

The obnoxious person may not be guilty of any crime . . . but if, in the opinion of the local authorities, his presence in a particular place is “prejudicial to public order” or “incompatible with public tranquility,” he may be arrested without warrant, may be held from two weeks to two years in prison, and may then be removed by force to any other place within the limits of the empire and there be put under police surveillance for a period of from one to ten years.

Warrantless seizures, surveillance, indefinite detention, isolation, exile… sound familiar?

It should.

The age-old practice by which despotic regimes eliminate their critics or potential adversaries by making them disappear—or forcing them to flee—or exiling them literally or figuratively or virtually from their fellow citizens—is happening with increasing frequency in America.

Now, through the use of red flag laws, behavioral threat assessments, and pre-crime policing prevention programs, the groundwork is being laid that would allow the government to weaponize the label of mental illness as a means of exiling those whistleblowers, dissidents and freedom fighters who refuse to march in lockstep with its dictates.

That the government is using the charge of mental illness as the means by which to immobilize (and disarm) its critics is diabolical. With one stroke of a magistrate’s pen, these individuals are declared mentally ill, locked away against their will, and stripped of their constitutional rights.

These developments are merely the realization of various U.S. government initiatives dating back to 2009, including one dubbed Operation Vigilant Eagle which calls for surveillance of military veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, characterizing them as extremists and potential domestic terrorist threats because they may be “disgruntled, disillusioned or suffering from the psychological effects of war.”

Coupled with the report on “Rightwing Extremism: Current Economic and Political Climate Fueling Resurgence in Radicalization and Recruitment” issued by the Department of Homeland Security (curiously enough, a Soviet term), which broadly defines rightwing extremists as individuals and groups “that are mainly antigovernment, rejecting federal authority in favor of state or local authority, or rejecting government authority entirely,” these tactics bode ill for anyone seen as opposing the government.

Thus, what began as a blueprint under the Bush administration has since become an operation manual for exiling those who challenge the government’s authority.

An important point to consider, however, is that the government is not merely targeting individuals who are voicing their discontent so much as it is locking up individuals trained in military warfare who are voicing feelings of discontent.

Under the guise of mental health treatment and with the complicity of government psychiatrists and law enforcement officials, these veterans are increasingly being portrayed as ticking time bombs in need of intervention.

For instance, the Justice Department launched a pilot program aimed at training SWAT teams to deal with confrontations involving highly trained and often heavily armed combat veterans.

One tactic being used to deal with so-called “mentally ill suspects who also happen to be trained in modern warfare” is through the use of civil commitment laws, found in all states and employed throughout American history to not only silence but cause dissidents to disappear.

For example, NSA officials attempted to label former employee Russ Tice, who was willing to testify in Congress about the NSA’s warrantless wiretapping program, as “mentally unbalanced” based upon two psychiatric evaluations ordered by his superiors.

NYPD Officer Adrian Schoolcraft had his home raided, and he was handcuffed to a gurney and taken into emergency custody for an alleged psychiatric episode. It was later discovered by way of an internal investigation that his superiors were retaliating against him for reporting police misconduct. Schoolcraft spent six days in the mental facility, and as a further indignity, was presented with a bill for $7,185 upon his release.

Marine Brandon Raub—a 9/11 truther—was arrested and detained in a psychiatric ward under Virginia’s civil commitment law based on posts he had made on his Facebook page that were critical of the government.

Each state has its own set of civil, or involuntary, commitment laws. These laws are extensions of two legal principles: parens patriae Parens patriae (Latin for “parent of the country”), which allows the government to intervene on behalf of citizens who cannot act in their own best interest, and police power, which requires a state to protect the interests of its citizens.

The fusion of these two principles, coupled with a shift towards a dangerousness standard, has resulted in a Nanny State mindset carried out with the militant force of the Police State.

The problem, of course, is that the diagnosis of mental illness, while a legitimate concern for some Americans, has over time become a convenient means by which the government and its corporate partners can penalize certain “unacceptable” social behaviors.

In fact, in recent years, we have witnessed the pathologizing of individuals who resist authority as suffering from oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), defined as “a pattern of disobedient, hostile, and defiant behavior toward authority figures.” Under such a definition, every activist of note throughout our history—from Mahatma Gandhi to Martin Luther King Jr.—could be classified as suffering from an ODD mental disorder.

Of course, this is all part of a larger trend in American governance whereby dissent is criminalized and pathologized, and dissenters are censored, silenced, declared unfit for society, labelled dangerous or extremist, or turned into outcasts and exiled.

Red flag gun laws (which authorize government officials to seize guns from individuals viewed as a danger to themselves or others), are a perfect example of this mindset at work and the ramifications of where this could lead.

As The Washington Post reports, these red flag gun laws “allow a family member, roommate, beau, law enforcement officer or any type of medical professional to file a petition [with a court] asking that a person’s home be temporarily cleared of firearms. It doesn’t require a mental-health diagnosis or an arrest.”

With these red flag gun laws, the stated intention is to disarm individuals who are potential threats.

While in theory it appears perfectly reasonable to want to disarm individuals who are clearly suicidal and/or pose an “immediate danger” to themselves or others, where the problem arises is when you put the power to determine who is a potential danger in the hands of government agencies, the courts and the police.

Remember, this is the same government that uses the words “anti-government,” “extremist” and “terrorist” interchangeably.

This is the same government whose agents are spinning a sticky spider-web of threat assessments, behavioral sensing warnings, flagged “words,” and “suspicious” activity reports using automated eyes and ears, social media, behavior sensing software, and citizen spies to identify potential threats.

This is the same government that keeps re-upping the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which allows the military to detain American citizens with no access to friends, family or the courts if the government believes them to be a threat.

This is the same government that has a growing list—shared with fusion centers and law enforcement agencies—of ideologies, behaviors, affiliations and other characteristics that could flag someone as suspicious and result in their being labeled potential enemies of the state.

For instance, if you believe in and exercise your rights under the Constitution (namely, your right to speak freely, worship freely, associate with like-minded individuals who share your political views, criticize the government, own a weapon, demand a warrant before being questioned or searched, or any other activity viewed as potentially anti-government, racist, bigoted, anarchic or sovereign), you could be at the top of the government’s terrorism watch list.

Moreover, as a New York Times editorial warns, you may be an anti-government extremist (a.k.a. domestic terrorist) in the eyes of the police if you are afraid that the government is plotting to confiscate your firearms, if you believe the economy is about to collapse and the government will soon declare martial law, or if you display an unusual number of political and/or ideological bumper stickers on your car.

Let that sink in a moment.

Now consider the ramifications of giving police that kind of authority in order to preemptively neutralize a potential threat, and you’ll understand why some might view these mental health round-ups with trepidation.

No matter how well-meaning the politicians make these encroachments on our rights appear, in the right (or wrong) hands, benevolent plans can easily be put to malevolent purposes.

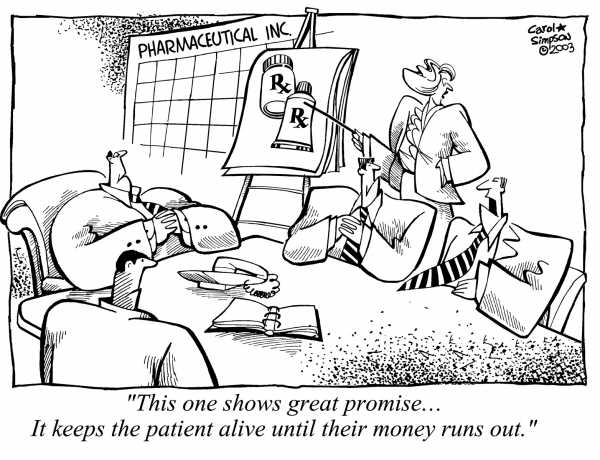

Even the most well-intentioned government law or program can be—and has been—perverted, corrupted and used to advance illegitimate purposes once profit and power are added to the equation.

The war on terror, the war on drugs, the war on illegal immigration, the war on COVID-19: all of these programs started out as legitimate responses to pressing concerns and have since become weapons of compliance and control in the government’s hands. For instance, the very same mass surveillance technologies that were supposedly so necessary to fight the spread of COVID-19 are now being used to stifle dissent, persecute activists, harass marginalized communities, and link people’s health information to other surveillance and law enforcement tools.

As I make clear in my book Battlefield America: The War on the American People and in its fictional counterpart The Erik Blair Diaries, we are moving fast down that slippery slope to an authoritarian society in which the only opinions, ideas and speech expressed are the ones permitted by the government and its corporate cohorts.

We stand at a crossroads.

As author Erich Fromm warned, “At this point in history, the capacity to doubt, to criticize and to disobey may be all that stands between a future for mankind and the end of civilization.”