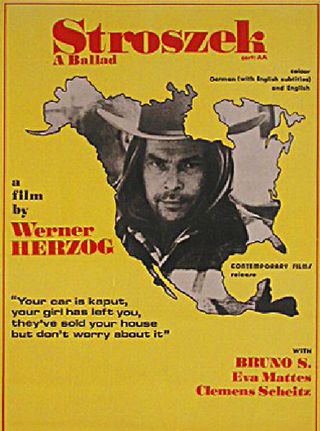

Classic Film Review: Herzog’s take on Germany-and-America-in-the-70s — “Stroszek”

By Roger Moore

Source: Roger’s Movie Nation

Long before he became the German filmmaker whose somber, ironic narrations and bleakly beautiful and humanistic documentaries turned Werner Herzog into a pop culture icon, he was a cult figure among international cinema fans.

In his early years of fame, Herzog’s movies could be dark, naturalistic poetry, or ambitious, cast-and-crew-testing living nightmares. His alter ego in the latter films was the bug-eyed maniac Klaus Kinski (“Aguirre: The Wrath of God,” “Nosferatu the Vampire, “”Woyzeck,” Fitzcarraldo”). Herzog later made a documentary tribute to their difficult working relationship, “My Best Fiend.”

But his co-conspirator/muse for the strange, personal and very human character studies “The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser” and “Stroszek” was the eccentric, troubled forklift driver and self-taught street musician Bruno Schleinstein, known in Herzog’s films and to the film world as simply “Bruno S.”

“Stroszek” is a tone poem of a shattered life that comes to cling to one last broken dream. It’s a statement on the disconnect between 1977 Europe and America, particularly rural America, as seen through a delusional and alcoholic street musician with no visible means of support who moves from Berlin to BFE, Wisconsin in a country where “everybody gets rich” and The American Dream, at least as Cold War-weary Germans saw it, could come true.

It’s bleak and tragic, and funny in the darkest ways. It’s the sort of film that seemed very much of its time in its time, but that inspired generations of indie filmmakers to seek out the unheralded inhabitants of whatever underbelly of life was close at hand, and the sort of eccentrics who might be living in it.

Bruno is a theatrical goofball of inmate who loudly jokes through his entire paroling out of a Berlin jail. Some of his warders want to know, after all the time he’s served, if he’s been “dropped on the head?” The warden hectors him over his “beer” and goes on and on (in German with English subtitles) about how he should “never touch another drop” and “never set foot in a pub.”

Garrulous Bruno seems to agree, right up to the moment he rolls into his neighborhood watering hole on his way home.

A couple of brutish pimps are berating and knocking around Eva (Eva Mattes), whom Bruno sees as his “girl.” He doesn’t even try to defend her. But he invites her to live with him, with hopes of taking care of her. It’s just that his cluttered flat full of musical instruments which he’s taught himself to play, from the piano and accordion to the mellotron and glockenspiel, seems to defy that expecation.

And Eva’s lot gets worse when her pimps drag her out and back to work, and then bring her back, beating Bruno and humiliating him in front of her as they do. Their only way out may be accompanying their elderly neighbor (Clemens Scheitz) to stay with his nephew in Railroad Flats, Wisconsin.

So that’s what they do, losing Bruno’s mynah bird in U.S. customs, buying a used station wagon and trekking cross country to this place they can barely find on a map.

Clayton (Clayton Szalpinski) is a simple Air Force veteran running a garage in a one-stoplight town on the Northern Plains. He scrapes out a living, adds Bruno to his garage staff (Ely Rodriguez already works there) and shows them around a tiny, dead town where “murders” happen, where farmers feuding over a tiny parcel of land between their adjoining farms ride their tractors with a rifle in their spare hand.

But at least there’s a local truck stop where Eva can wait tables. As Bruno and Eva set up housekeeping, buying a new single-wide and a ruinously-expensive Sylvania TV, Eva is almost certain to have to resume her old career if they’re to make ends meet.

“Stroszek” is a leisurely, contemplative character study with music, as Herzog gives Bruno S. room to let us see into his soul through his musicianship, his fondness for playing and singing to no audience in big, echoey, empty courtyards and such. The Country Muzak of guitarist Chet Atkins’ instrumentals underscores many of the North American scenes.

One evokes memories of the Old World, where the buildings and people seem ancient and set on life’s path by their circumstances. Bruno S., playing a version of himself, is an orphan whose prostitute mother didn’t want him. Life in both worlds has its tests but the nature of the struggles are different, with the promise of America, a land of plenty undercut by the never-ending quest and need for money, which the “proletarian” Bruno starts to see as a “conspiracy.”

In its day, “Stroszek” was celebrated as a soulful bolt out of the blue in an American film landscape just turning itself over to the blockbuster. Lore grew up around the film and the seat-of-the-pants way Herzog filmed it (driving scenes with no camera truck/trailer) and scripted it, working around his screwy leading man’s moods, filming much of it Nekoosa and Plainfield, Wisconsin, with a conjured up tourist-trap-in-winter-finale filmed in Cherokee, N.C.

Viewed today, its whimsical charms stand out more than its tragic overtones. Even back then, critics and culture observers were pondering why American cinema made so little effort to find and celebrate the Brunos in our midst.

But documentary filmmakers Errol Morris and Les Blank, early disciples of Herzog and credited in “Stroszek,” are Americans who achieved their first fame for finding and lauding the quirkiness in the vast United States between the coasts.

And then the indie cinema of the ’80s and ’90s came along and amplified queer lives and rural despair, urban struggle and generational angst. By that time, their acknowledged or unacknowledged icon, the pioneering Herzog, had shifted more to the documentary side (“Grizzly Man,” “Cave of Forgotten Dreams”) and become an actor and personality far more famous than the movies that first made him.

But quaint as it sometimes seems now, “Stroszek” remains one of the touchstone films of an era whose very look on screen — grey and gritty and forboding — is as instantly identifiable as its often more sober-minded and cynical subject matter and the inimatable characters inhabiting it.

Watch Stroszek on Tubi here: https://tubitv.com/movies/268904/stroszek