By Paul Street

Source: Consortium News

There are good reasons to bemoan the presence of the childish, racist, sexist and ecocidal, right-wing plutocrat Donald Trump in the White House. One complaint about Trump that should be held at arm’s-length by anyone on the left, however, is the charge that Trump is contributing to the decline of U.S. global power—to the erosion of the United States’ superpower status and the emergence of a more multipolar world.

This criticism of Trump comes from different elite corners. Last October, the leading neoconservative foreign policy intellectual and former George W. Bush administration adviser Eliot Cohen wrote an Atlantic magazine essay titled “How Trump Is Ending the American Era.” Cohen recounted numerous ways in which Trump had reduced “America’s standing and ability to influence global affairs.” He worried that Trump’s presidency would leave “America’s position in the world stunted” and an “America lacking confidence” on the global stage.

But it isn’t just the right wing that writes and speaks in such terms about how Trump is contributing to the decline of U.S. hegemony. A recent Time magazine reflection by the liberal commentator Karl Vick (who wrote in strongly supportive terms about the giant January 2017 Women’s March against Trump) frets that that Trump’s “America First” and authoritarian views have the world “looking for leadership elsewhere.”

“Could this be it?” Vick asks. “Might the American Century actually clock out at just 72 years, from 1945 to 2017? No longer than Louis XIV ruled France? Only 36 months more than the Soviet Union lasted, after all that bother?”

I recently reviewed a manuscript on the rise of Trump written by a left-liberal American sociologist. Near the end of this forthcoming and mostly excellent and instructive volume, the author finds it “worrisome” that other nations see the U.S. “abdicating its role as the world’s leading policeman” under Trump—and that, “given what we have seen so far from the [Trump] administration, U.S. hegemony appears to be on shakier ground than it has been in a long time.”

I’ll leave aside the matter of whether Trump is, in fact, speeding the decline of U.S. global power (he undoubtedly is) and how he’s doing that, to focus instead on a very different question: What would be so awful about the end of “the American Era”—the seven-plus decades of U.S. global economic and related military supremacy between 1945 and the present? Why should the world mourn the “premature” end of the “American Century”?

What Would the Rest of the World Say?

It would be interesting to see a reliable opinion poll on how the politically cognizant portion of the 94 percent of humanity that lives outside the U.S. would feel about the end of U.S. global dominance. My guess is that Uncle Sam’s weakening would be just fine with most Earth residents who pay attention to world events.

According to a global survey of 66,000 people conducted across 68 countries by the Worldwide Independent Network of Market Research (WINMR) and Gallup International at the end of 2013, Earth’s people see the United States as the leading threat to peace on the planet. The U.S. was voted top threat by a wide margin.

There is nothing surprising about that vote for anyone who honestly examines the history of “U.S. foreign affairs,” to use a common elite euphemism for American imperialism. Still, by far and away world history’s most extensive empire, the U.S. has at least 800 military bases spread across more than 80 foreign countries and “troops or other military personnel in about 160

foreign countries and territories.” The U.S. accounts for more than 40 percent of the planet’s military spending and has more than 5,500 strategic nuclear weapons, enough to blow the world up 5 to 50 times over. Last year it increased its “defense” (military empire) spending, which was already three times higher than China’s, and nine times higher than Russia’s.

Think it’s all in place to ensure peace and democracy the world over, in accord with the standard boilerplate rhetoric of U.S. presidents, diplomats and senators?

Do you know any other good jokes?

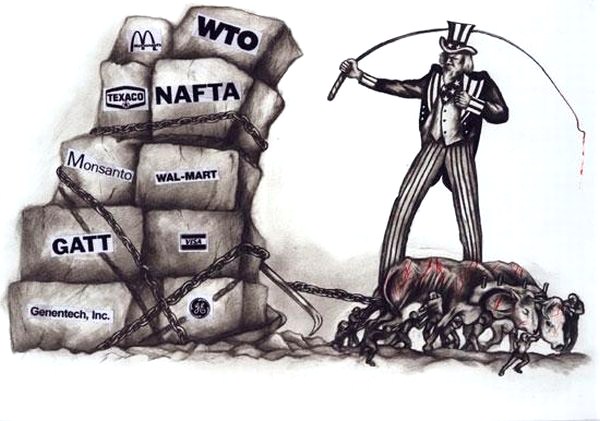

A Pentagon study released last summer laments the emergence of a planet on which the U.S. no longer controls events. Titled “At Our Own Peril: DoD Risk Assessment in a Post-Primary World,” the study warns that competing powers “seek a new distribution of power and authority commensurate with their emergence as legitimate rivals to U.S. dominance” in an increasingly multipolar world. China, Russia and smaller players like Iran and North Korea have dared to “engage,” the Pentagon study reports, “in a deliberate program to demonstrate the limits of U.S. authority, reach influence and impact.” What chutzpah! This is a problem, the report argues, because the endangered U.S.-managed world order was “favorable” to the interests of U.S. and allied U.S. states and U.S.-based transnational corporations.

Any serious efforts to redesign the international status quo so that it favors any other states or people is portrayed in the report as a threat to U.S. interests. To prevent any terrible drifts of the world system away from U.S. control, the report argues, the U.S. and its imperial partners (chiefly its European NATO partners) must maintain and expand “unimpeded access to the air, sea, space, cyberspace, and the electromagnetic spectrum in order to underwrite their security and prosperity.” The report recommends a significant expansion of U.S. military power. The U.S. must maintain “military advantage” over all other states and actors to “preserve maximum freedom of action” and thereby “allow U.S. decision-makers the opportunity to dictate or hold significant sway over outcomes in international disputes,” with the “implied promise of unacceptable consequences” for those who defy U.S. wishes.

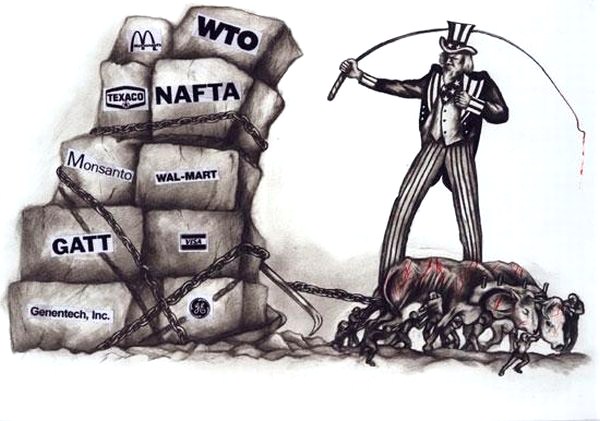

“America First” is an understatement here. The underlying premise is that Uncle Sam owns the world and reserves the right to bomb the hell out of anyone who doesn’t agree with that (to quote President George H.W. Bush after the first Gulf War in 1991: “What we say goes.”

Investment Not Democracy

It’s nothing new. From the start, the “American Century” had nothing to do with advancing democracy. As numerous key U.S. planning documents reveal over and over, the goal of that policy was to maintain and, if necessary, install governments that “favor[ed] private investment of domestic and foreign capital, production for export, and the right to bring profits out of the country,” according to Noam Chomsky. Given the United States’ remarkable possession of half the world’s capital after World War II, Washington elites had no doubt that U.S. investors and corporations would profit the most. Internally, the basic selfish national and imperial objectives were openly and candidly discussed. As the “liberal” and “dovish” imperialist, top State Department planner, and key Cold War architect George F. Kennan explained in “Policy Planning Study 23,” a critical 1948 document:

We have about 50% of the world’s wealth, but only 6.3% of its population. … In this situation, we cannot fail to be the object of envy and resentment. Our real task in the coming period is to devise a pattern of relationships which will permit us to maintain this position of disparity. … To do so, we will have to dispense with all sentimentality and day-dreaming; and our attention will have to be concentrated everywhere on our immediate national objectives. … We should cease to talk about vague and … unreal objectives such as human rights, the raising of the living standards, and democratization. The day is not far off when we are going to have to deal in straight power concepts. The less we are then hampered by idealistic slogans, the better.

The harsh necessity of abandoning “human rights” and other “sentimental” and “unreal objectives” was especially pressing in the global South, what used to be known as the Third World. Washington assigned the vast “undeveloped” periphery of the world capitalist system—Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia and the energy-rich and thus strategically hyper-significant Middle East—a less than flattering role. It was to “fulfill its major function as a source of raw materials and a market” (actual State Department language) for the great industrial (capitalist) nations (excluding socialist Russia and its satellites, and notwithstanding the recent epic racist-fascist rampages of industrial Germany and Japan). It was to be exploited both for the benefit of U.S. corporations/investors and for the reconstruction of Europe and Japan as prosperous U.S. trading and investment partners organized on capitalist principles and hostile to the Soviet bloc.

“Democracy” was fine as a slogan and benevolent, idealistic-sounding mission statement when it came to marketing this imperialist U.S. policy at home and abroad. Since most people in the “third” or “developing” world had no interest in neocolonial subordination to the rich nations and subscribed to what U.S. intelligence officials considered the heretical “idea that government has direct responsibility for the welfare of its people” (what U.S. planners called “communism”), Washington’s real-life commitment to popular governance abroad was strictly qualified, to say the least.

“Democracy” was suitable to the U.S. as long as its outcomes comported with the interests of U.S. investors/corporations and related U.S. geopolitical objectives. Democracy had to be abandoned, undermined and/or crushed when it threatened those investors/corporations and the broader imperatives of business rule to any significant degree. As President Richard Nixon’s coldblooded national security adviser Henry Kissinger explained in June 1970, three years before the U.S. sponsored a bloody fascist coup that overthrew Chile’s democratically elected socialist president, Salvador Allende: “I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go Communist because of the irresponsibility of its own people.”

The U.S.-sponsored coup government that murdered Allende would kill tens of thousands of real and alleged leftists with Washington’s approval. The Yankee superpower sent some of its leading neoliberal economists and policy advisers to help the blood-soaked Pinochet regime turn Chile into a “free market” model and to help Chile write capitalist oligarchy into its national constitution.

“Since 1945, by deed and by example,” the great Australian author, commentator and filmmaker John Pilger wrote nearly nine years ago, “the U.S. has overthrown 50 governments, including democracies, crushed some 30 liberation movements and supported tyrannies from Egypt to Guatemala (see William Blum’s histories). Bombing is apple pie.” Along the way, Washington has crassly interfered in elections in dozens of “sovereign” nations, something curious to note in light of current liberal U.S. outrage over real or alleged Russian interference in “our” supposedly democratic electoral process in 2016. Uncle Sam also has bombed civilians in 30 countries, attempted to assassinate foreign leaders and deployed chemical and biological weapons.

If we “consider only Latin America since the 1950s,” writes the sociologist Howard Waitzkin:

[T]he United States has used direct military invasion or has supported military coups to overthrow elected governments in Guatemala, the Dominican Republic, Chile, Haiti, Grenada, and Panama. In addition, the United States has intervened with military action to suppress revolutionary movements in El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Bolivia. More recently … the United States has spent tax dollars to finance and help organize opposition groups and media in Honduras, Paraguay, and Brazil, leading to congressional impeachments of democratically elected presidents. Hillary Clinton presided over these efforts as Secretary of State in the Obama administration, which pursued the same pattern of destabilization in Venezuela, Ecuador, Argentina, Chile, and Bolivia.

Death Count: In the Millions

The death count resulting from “American Era” U.S. foreign policy runs well into the many millions, including possibly as many as 5 million Indochinese killed by Uncle Sam and his agents and allies between 1962 and 1975. The flat-out barbarism of the American war on Vietnam is widely documented on record. The infamous My Lai massacre of March 16, 1968, when U.S. Army soldiers slaughtered more than 350 unarmed civilians—including terrified women holding babies in their arms—in South Vietnam was no isolated incident in the U.S. “crucifixion of Southeast Asia” (Noam Chomsky’s phrase at the time). U.S. Army Col. Oran Henderson, who was charged with covering up the massacre, candidly told reporters that “every unit of brigade size has its My Lai hidden somewhere.”

It is difficult, sometimes, to wrap one’s mind around the extent of the savagery the U.S. has unleashed on the world to advance and maintain its global supremacy. In the early 1950s, the Harry Truman administration responded to an early challenge to U.S. power in Northern Korea with a practically genocidal three-year bombing campaign that was described in soul-numbing terms by the Washington Post years ago:

The bombing was long, leisurely and merciless, even by the assessment of America’s own leaders. ‘Over a period of three years or so, we killed off—what—20 percent of the population,’ Air Force Gen. Curtis LeMay, head of the Strategic Air Command during the Korean War, told the Office of Air Force History in 1984. Dean Rusk, a supporter of the war and later Secretary of State, said the United States bombed ‘everything that moved in North Korea, every brick standing on top of another.’ After running low on urban targets, U.S. bombers destroyed hydroelectric and irrigation dams in the later stages of the war, flooding farmland and destroying crops … [T]he U.S. dropped 635,000 tons of explosives on North Korea, including 32,557 tons of napalm, an incendiary liquid that can clear forested areas and cause devastating burns to human skin.

Gee, why does North Korea fear and hate us?

This ferocious bombardment, which killed 2 million or more civilians, began five years after Truman arch-criminally and unnecessarily ordered the atom bombing of hundreds of thousands pf civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki to warn the Soviet Union to stay out of Japan and Western Europe.

Some benevolent “world policeman.”

The ferocity of U.S. foreign policy in the “America Era” did not always require direct U.S. military intervention. Take Indonesia and Chile, for two examples from the “Golden Age” height of the “American Century.” In Indonesia, the U.S.-backed dictator Suharto killed millions of his subjects, targeting communist sympathizers, ethnic Chinese and alleged leftists. A senior CIA operations officer in the 1960s later described Suharto’s 1965-66 U.S.-assisted coup as s “the model operation” for the U.S.-backed coup that eliminated the democratically elected president of Chile, Salvador Allende, seven years later. “The CIA forged a document purporting to reveal a leftist plot to murder Chilean military leaders,” the officer wrote, “[just like] what happened in Indonesia in 1965.”

As Pilger noted 10 years ago, “the U.S. embassy in Jakarta supplied Suharto with a ‘zap list’ of Indonesian Communist party members and crossed off the names when they were killed or captured. … The deal was that Indonesia under Suharto would offer up what Richard Nixon had called ‘the richest hoard of natural resources, the greatest prize in south-east Asia.’ ”

“No single American action in the period after 1945,” wrote the historian Gabriel Kolko, “was as bloodthirsty as its role in Indonesia, for it tried to initiate [Suharto’s] massacre.”

Two years and three months after the Chilean coup, Suharto received a green light from Kissinger and the Gerald Ford White House to invade the small island nation of East Timor. With Washington’s approval and backing, Indonesia carried out genocidal massacres and mass rapes and killed at least 100,000 of the island’s residents.

Mideast Savagery

Among the countless episodes of mass-murderous U.S. savagery in the oil-rich Middle East over the last generation, few can match for the barbarous ferocity of the “Highway of Death,” where the “global policeman’s” forces massacred tens of thousands of surrendered Iraqi troops retreating from Kuwait on Feb. 26 and 27, 1991. Journalist Joyce Chediac testified that:

U.S. planes trapped the long convoys by disabling vehicles in the front, and at the rear, and then pounded the resulting traffic jams for hours. ‘It was like shooting fish in a barrel,’ said one U.S. pilot. On the sixty miles of coastal highway, Iraqi military units sit in gruesome repose, scorched skeletons of vehicles and men alike, black and awful under the sun … for 60 miles every vehicle was strafed or bombed, every windshield is shattered, every tank is burned, every truck is riddled with shell fragments. No survivors are known or likely. … ‘Even in Vietnam I didn’t see anything like this. It’s pathetic,’ said Major Bob Nugent, an Army intelligence officer. … U.S. pilots took whatever bombs happened to be close to the flight deck, from cluster bombs to 500-pound bombs. … U.S. forces continued to drop bombs on the convoys until all humans were killed. So many jets swarmed over the inland road that it created an aerial traffic jam, and combat air controllers feared midair collisions. … The victims were not offering resistance. … [I]t was simply a one-sided massacre of tens of thousands of people who had no ability to fight back or defend.

The victims’ crime was having been conscripted into an army controlled by a dictator perceived as a threat to U.S. control of Middle Eastern oil. President George H.W. Bush welcomed the so-called Persian Gulf War as an opportunity to demonstrate America’s unrivaled power and new freedom of action in the post-Cold War world, where the Soviet Union could no longer deter Washington. Bush also heralded the “war” (really a one-sided imperial assault) as marking the end of the “Vietnam Syndrome,” the reigning political culture’s curious term for U.S. citizens’ reluctance to commit U.S. troops to murderous imperial mayhem.

As Chomsky observed in 1992, reflecting on U.S. efforts to maximize suffering in Vietnam by blocking economic and humanitarian assistance to the nation it had devastated: “No degree of cruelty is too great for Washington sadists.”

But Uncle Sam was only getting warmed up building his Iraqi body count in early 1991. Five years later, Bill Clinton’s U.S. Secretary of State Madeline Albright told CBS News’ Leslie Stahl that the death of 500,000 Iraqi children due to U.S.-led economic sanctions imposed after the first “Persian Gulf War” (a curious term for a one-sided U.S. assault) was a “price … worth paying” for the advancement of inherently noble U.S. goals.

“The United States,” Secretary Albright explained three years later, “is good. We try to do our best everywhere.”

In the years following the collapse of the counter-hegemonic Soviet empire, however, American neoliberal intellectuals like Thomas Friedman—an advocate of the criminal U.S. bombing of Serbia—felt free to openly state that the real purpose of U.S. foreign policy was to underwrite the profits of U.S.-centered global capitalism. “The hidden hand of the market,” Friedman famously wrote in The New York Times Magazine in March 1999, as U.S. bombs and missiles exploded in Serbia, “will never work without a hidden fist. McDonald’s cannot flourish without McDonnell Douglas, the designer of the F-15. And the hidden fist that keeps the world safe for Silicon Valley’s technologies to flourish is called the U.S. Army, Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps.”

In a foreign policy speech Sen. Barack Obama gave to the Chicago Council of Global Affairs on the eve of announcing his candidacy for the U.S. presidency in the fall of 2006, Obama had the audacity to say the following in support of his claim that U.S. citizens supported “victory” in Iraq: “The American people have been extraordinarily resolved. They have seen their sons and daughters killed or wounded in the streets of Fallujah.”

It was a spine-chilling selection of locales. In 2004, the ill-fated city was the site of colossal U.S. war atrocities, crimes including the indiscriminate murder of thousands of civilians, the targeting even of ambulances and hospitals, and the practical leveling of an entire city by the U.S. military in April and November. By one account, “Incoherent Empire,” Michael Mann wrote:

The U.S. launched two bursts of ferocious assault on the city, in April and November of 2004 … [using] devastating firepower from a distance which minimizes U.S. casualties. In April … military commanders claimed to have precisely targeted … insurgent forces, yet the local hospitals reported that many or most of the casualties were civilians, often women, children, and the elderly… [reflecting an] intention to kill civilians generally. … In November … [U.S.] aerial assault destroyed the only hospital in insurgent territory to ensure that this time no one would be able to document civilian casualties. U.S. forces then went through the city, virtually destroying it. Afterwards, Fallujah looked like the city of Grozny in Chechnya after Putin’s Russian troops had razed it to the ground.

The “global policeman’s” deployment of radioactive ordnance (depleted uranium) in Fallujah created an epidemic of infant mortality, birth defects, leukemia and cancer there.

‘Bug-Splat’

Fallujah was just one especially graphic episode in a broader arch-criminal invasion that led to the premature deaths of at least 1 million Iraqi civilians and left Iraq as what Tom Engelhardt called “a disaster zone on a catastrophic scale hard to match in recent memory.” It reflected the same callous mindset behind the Pentagon’s early computer program name for ordinary Iraqis certain to be killed in the 2003 invasion: “bug-splat.” America’s petro-imperial occupation led to the death of as many as one million Iraqi “bugs” (human beings). According to the respected journalist Nir Rosen in December 2007, “Iraq has been killed. … [T]he American occupation has been more disastrous than that of the Mongols who sacked Baghdad in the thirteenth century.”

As the Senate is poised to confirm an alleged torturer as CIA director it is important to remember that along with death in Iraq came ruthless and racist torture. In an essay titled “I Helped Create ISIS,” Vincent Emanuele, a former U.S. Marine, recalled his enlistment in an operation that gave him nightmares more than a decade later:

I think about the hundreds of prisoners we took captive and tortured in makeshift detention facilities. … I vividly remember the marines telling me about punching, slapping, kicking, elbowing, kneeing and head-butting Iraqis. I remember the tales of sexual torture: forcing Iraqi men to perform sexual acts on each other while marines held knives against their testicles, sometimes sodomizing them with batons. … [T]hose of us in infantry units … round[ed] up Iraqis during night raids, zip-tying their hands, black-bagging their heads and throwing them in the back of HUMVEEs and trucks while their wives and kids collapsed to their knees and wailed. … Some of them would hold hands while marines would butt-stroke the prisoners in the face. … [W]hen they were released, we would drive them from the FOB (Forward Operating Base) to the middle of the desert and release them several miles from their homes. … After we cut their zip-ties and took the black bags off their heads, several of our more deranged marines would fire rounds from their AR-15s into their air or ground, scaring the recently released captives. Always for laughs. Most Iraqis would run, still crying from their long ordeal.

The award-winning journalist Seymour Hersh told the ACLU about the existence of classified Pentagon evidence files containing films of U.S-“global policeman” soldiers sodomizing Iraqi boys in front of their mothers behind the walls of the notorious Abu Ghraib prison. “You haven’t begun to see [all the] … evil, horrible things done [by U.S. soldiers] to children of women prisoners, as the cameras run,” Hersh told an audience in Chicago in the summer of 2014.

It isn’t just Iraq where Washington has wreaked sheer mass murderous havoc in the Middle East, always a region of prime strategic significance to the U.S. thanks to its massive petroleum resources. In a recent Truthdig reflection on Syria, historian Dan Lazare reminds us that:

[Syrian President Assad’s] Baathist crimes pale in comparison to those of the U.S., which since the 1970s has invested trillions in militarizing the Persian Gulf and arming the ultra-reactionary petro-monarchies that are now tearing the region apart. The U.S. has provided Saudi Arabia with crucial assistance in its war on Yemen, it has cheered on the Saudi blockade of Qatar, and it has stood by while the Saudis and United Arab Emirates send in troops to crush democratic protests in neighboring Bahrain. In Syria, Washington has worked hand in glove with Riyadh to organize and finance a Wahhabist holy war that has reduced a once thriving country to ruin.

Chomsky has called Barack Obama’s targeted drone assassination program “the most extensive global terrorism campaign the world has yet seen.” The program “officially is aimed at killing people who the administration believes might someday intend to harm the U.S. and killing anyone else who happens to be nearby.” As Chomsky adds, “It is also a terrorism generating campaign—that is well understood by people in high places. When you murder somebody in a Yemen village, and maybe a couple of other people who are standing there, the chances are pretty high that others will want to take revenge.”

The Last, Best Hope

“We lead the world,” presidential candidate Obama explained, “in battling immediate evils and promoting the ultimate good. … America is the last, best hope of earth.”

Obama elaborated in his first inaugural address. “Our security,” the president said, “emanates from the justness of our cause; the force of our example; the tempering qualities of humility and restraint”—a fascinating commentary on Fallujah, Hiroshima, the U.S. crucifixion of Southeast Asia, the “Highway of Death” and more.

Within less than half a year of his inauguration and his lauded Cairo speech, Obama’s rapidly accumulating record of atrocities in the Muslim world would include the bombing of the Afghan village of Bola Boluk. Ninety-three of the dead villagers torn apart by U.S. explosives in Bola Boluk were children. “In a phone call played on a loudspeaker on Wednesday to outraged members of the Afghan Parliament,” The New York Times reported, “the governor of Farah Province … said that as many as 130 civilians had been killed.” According to one Afghan legislator and eyewitness, “the villagers bought two tractor trailers full of pieces of human bodies to his office to prove the casualties that had occurred. Everyone at the governor’s cried, watching that shocking scene.” The administration refused to issue an apology or to acknowledge the “global policeman’s” responsibility.

By telling and sickening contrast, Obama had just offered a full apology and fired a White House official because that official had scared New Yorkers with an ill-advised Air Force One photo-shoot flyover of Manhattan that reminded people of 9/11. The disparity was extraordinary: Frightening New Yorkers led to a full presidential apology and the discharge of a White House staffer. Killing more than 100 Afghan civilians did not require any apology.

Reflecting on such atrocities the following December, an Afghan villager was moved to comment as follows: “Peace prize? He’s a killer. … Obama has only brought war to our country.” The man spoke from the village of Armal, where a crowd of 100 gathered around the bodies of 12 people, one family from a single home. The 12 were killed, witnesses reported, by U.S. Special Forces during a late-night raid.

Obama was only warming up his “killer” powers. He would join with France and other NATO powers in the imperial decimation of Libya, which killed more than 25,000 civilians and unleashed mass carnage in North Africa. The U.S.-led assault on Libya was a disaster for black Africans and sparked the biggest refugee crisis since World War II.

Two years before the war on Libya, the Obama administration helped install a murderous right-wing coup regime in Honduras. Thousands of civilians and activists have been murdered by that regime.

The clumsy and stupid Trump has taken the imperial baton from the elegant and silver-tongued “imperial grandmaster” Obama, keeping the superpower’s vast global military machine set on kill. As Newsweek reported last fall, in a news item that went far below the national news radar screen in the age of the endless insane Trump clown show:

According to research from the nonprofit monitoring group Airwars … through the first seven months of the Trump administration, coalition air strikes have killed between 2,800 and 4,500 civilians. … Researchers also point to another stunning trend—the ‘frequent killing of entire families in likely coalition airstrikes.’ In May, for example, such actions led to the deaths of at least 57 women and 52 children in Iraq and Syria. … In Afghanistan, the U.N. reports a 67 percent increase in civilian deaths from U.S. airstrikes in the first six months of 2017 compared to the first half of 2016.

That Trump murders with less sophistication, outward moral restraint and credible claim to embody enlightened Western values and multilateral commitment than Obama did is perhaps preferable to some degree. It is better for empire to be exposed in its full and ugly nakedness, to speed its overdue demise.

The U.S. is not just the top menace only to peace on Earth. It is also the leading threat to personal privacy (as was made clearer than ever by the Edward Snowden revelations), to democracy (the U.S. funds and equips repressive regimes around the world) and to a livable global natural environment (thanks in no small part to its role as headquarters of global greenhouse gassing and petro-capitalist climate denial).

The world can be forgiven, perhaps, if it does not join Eliot Cohen and Karl Vick in bemoaning the end of the “American Era,” whatever Trump’s contribution to that decline, which was well underway before he entered the Oval Office.

Ordinary Americans, too, can find reasons to welcome the decline of the American empire. As Chomsky noted in the late 1960s: “The costs of empire are in general distributed over the society as a whole, while its profits revert to a few within.”

The Pentagon system functions as a great form of domestic corporate welfare for high-tech “defense” (empire) firms like Lockheed Martin, Boeing and Raytheon—this while it steals trillions of dollars that might otherwise meet social and environmental needs at home and abroad. It is a significant mode of upward wealth distribution within “the homeland.”

The biggest costs have fallen on the many millions killed and maimed by the U.S. military and allied and proxy forces in the last seven decades and before. The victims include the many U.S. military veterans who have killed themselves, many of them haunted by their own participation in sadistic attacks and torture on defenseless people at the distant command of sociopathic imperial masters determined to enforce U.S. hegemony by any and all means deemed necessary.