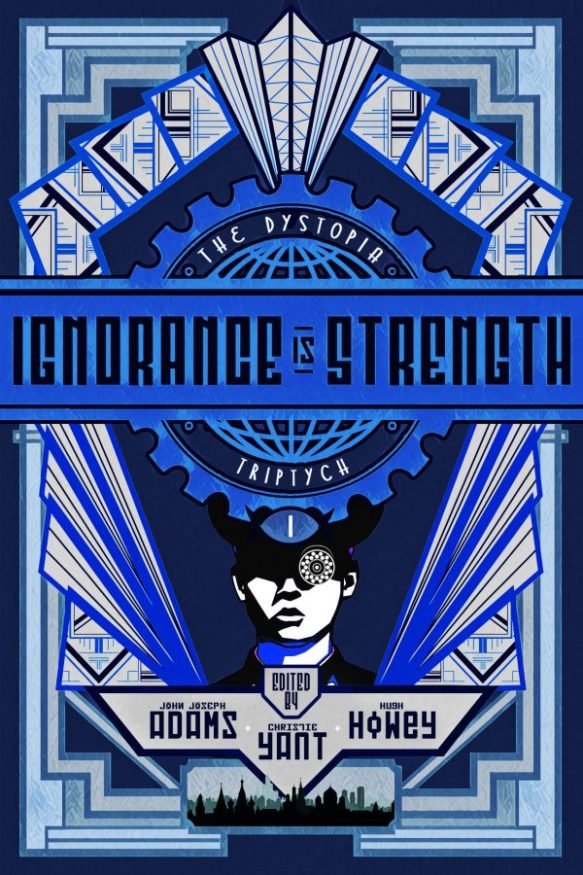

Cadwell Turnbull is a contributing author of The Dystopia Triptych. Photograph: Broad Reach Publishing

By Cadwell Turnbull

Source: Wired

Imagine a city where a group of people have managed against all odds to carve out prosperity for themselves, at least for a little while. These people used to be owned by other people. Now, they are permitted freedom, but only so much, subject to the whims of the once-masters.

Prosperity is a dangerous thing for the oppressed. It is a dry hot day in a forest bound to catch fire. And so, eventually, there is spark. A teenage boy assaults a teenage girl of the once-master class in an elevator, or so the story is told. Truth doesn’t matter here. A story is enough. The once-masters want justice, which means all the once-slaves must be punished. Men, women, and children are dragged from their homes and shot, their stores and houses bombed or burned. The exact number of dead will remain uncertain, the story buried for so long that people will watch it in a television show almost a century later and mistake the dramatization of the event for pure fiction.

Imagine another city where the once-slaves are told they are getting treatment for a devastating illness, when they are in fact receiving a placebo. Imagine four decades of this lie, the originally infected passing on this disease to their spouses, their children, so that the once-masters can study the long-term effects of the disease on people they don’t consider fully human.

Imagine these cities are part of a great nation. The once-slaves are tired of their second-class citizenship so they begin a movement for justice and equity. This movement is met with a violent backlash. The once-slaves are attacked by dogs, blasted by hoses. Their churches are burned, their institutions subject to random acts of retaliation by the once-masters. Their activists are monitored. Their leaders are jailed or assassinated. There are victories, but even after the successes, once-slaves are shot down in the street for minor offenses or looking “suspicious.” Their neighborhoods are over-policed. Their children are denied quality education. Many of them are sent to prison, where they work for pennies or for nothing. But it isn’t called slavery. It is treated as coincidence that this forced labor disproportionately affects the oppressed class, the once-slaves.

These are the makings of dystopian fictions, and yet many in America don’t need to imagine them. It is their reality. However, most Americans would not call America a dystopia.

If the edges are filed off, the names of places and events changed, a few injustices amplified, Americans can pretend the sorts of things that happen in dystopias don’t happen in their backyards. They can call it fiction, create enough distance to make themselves comfortable with their country’s own sins. But this doesn’t change the fact that the American experience is dystopian for many marginalized people. And like in any dystopia, real or imagined, it is up to all Americans to recognize this storyline, imagine a better society outside of the current reality, and then work toward it. Otherwise, America consents to a normal that is grotesque.

I read my first dystopia in high school. As a teenager, 1984 terrified the hell out of me. I didn’t read it as a warning, but as a mirror to my own experience. I identified with the protagonist Winston Smith’s feeling that something was deeply wrong with his society and the overwhelming sense of helplessness that followed. In college, I read my first utopia. The Dispossessed, by Ursula K. Le Guin, in every sense, was an antidote to that despair I felt when reading 1984.

And then, many years later, I read “The Day Before the Revolution,” the prequel short story to The Dispossessed, and found in it the practical application of the novel’s revolutionary ideas. The story is beautifully quiet. It follows Odo, the founder of the radical movement at the heart of The Dispossessed, as she goes through her day and remembers important moments in her political and personal journey. Le Guin prefaced “The Day Before the Revolution” with a brief definition of the Odonian belief system: “Odonianism is anarchism … its principal and moral-practical theme is cooperation (solidarity, mutual aid). It is the most idealistic, and to me the most interesting, of all political theories.”

To be clear, the Odonians are not perfect. They are resistant to change and have allowed other forms of institutional privilege to develop and calcify in their society. But, because they believe in their utopia and have lived their lives in accordance with that belief, they’ve managed to build a reasonably just and equitable society

And this is where, in life just as in science fiction, a distinction must be made. A just and equitable society is not the same as a perfect one. I’d argue that everyone would benefit if we defined utopia as a move toward justice and equity, and not just the state of perfection. But in America, especially in discussions about social justice, “just” and “perfect” are treated as synonymous objectives. And because perfect is never attainable, justice, too, becomes out of reach. Under this framing, injustice becomes normal, oppression is realistic, and any move towards justice and equity must come from struggle. A disturbing unspoken belief is born from this framing, that marginalized people will never receive full humanity because a just society is not possible. By failing to recognize the dystopia, and dismissing the possibility of a utopia, America has resigned itself to its current, dark narrative.

As a result, in America, universal social welfare is too costly and politically unfeasible, while trillion-dollar corporate bailouts and endless wars go unquestioned. Police and prison reform are aimed towards harm reduction for marginalized communities, instead of daring to imagine a society where these institutions are mostly unnecessary. In American discourse, a society can’t take care of all its citizens or remedy the causes of crime.

In a society where injustice is normalized, justice becomes a goal that can only be achieved through sacrifice—tragedy becomes currency, a thing to be used, not prevented. It takes decades of confirmed police brutality before America considers even the most minor reforms. This is not by accident. Black and brown bodies have been the fuel used to drive this society towards slightly lesser states of injustice since the very beginning. The oppressed have always paid the price for progress.

And yet, Americans have never shown this kind of defeatism when it comes to technological advancements. When this nation decided to go to the moon, it was framed in terms of “How do we get there?” not “Is this possible?” And no one ever said, “This rocket may only get half-way to the moon, but first many must die.”

Americans once oblivious to the dystopia are waking up. That’s good. But the price of waking up should be considered, and the lives sacrificed to incrementalism must be mourned. It is easy for a pragmatist to ask for incremental change when the current reality favors them. But pragmatism hits differently when it is forced at gunpoint. Every loss on the way to justice is a collective sin, because it was decided that the road must be long and the oppressed must struggle for every inch.

Do not normalize the losses happening right now because of the gains. Assume where America has always been is a tragedy. What is done in hell isn’t romantic; sacrificing bodies to dystopia isn’t beautiful. As I write this, people protesting brutality are dying at the hands of law enforcement. No one should pay for progress with their life. And it isn’t naive to believe every member of society should have a healthy, empowering, and fulfilling time on earth. The ones that have suffered deserve nothing less than faith in that possibility. This moment may provide a way out of dystopia, but there has to be a collective reckoning with the dystopian aspects of American society as well as the cruel price of progress repeatedly placed on the backs of the oppressed. Through solidarity there is a way out of these bitter realities, but the way there must be just if the destination is to be just.

In science fiction there is a notion that the universe is filled with possible worlds just waiting for humanity to come settle. It has some of its more troubling roots in manifest destiny, but also in hope, and the idea that better worlds are possible. But what if this corner of Earth could be that imagined place? Imagine a better world right here, instead of elsewhere. The price is in going all the way, doing all the work, believing all the work can be done. That’s the only way to get to the moon. Human beings have to believe it exists.