By John W. Whitehead

Source: The Rutherford Institute

“The Internet is watching us now. If they want to. They can see what sites you visit. In the future, television will be watching us, and customizing itself to what it knows about us. The thrilling thing is, that will make us feel we’re part of the medium. The scary thing is, we’ll lose our right to privacy. An ad will appear in the air around us, talking directly to us.”—Director Steven Spielberg, Minority Report

We have arrived, way ahead of schedule, into the dystopian future dreamed up by such science fiction writers as George Orwell, Aldous Huxley, Margaret Atwood and Philip K. Dick.

Much like Orwell’s Big Brother in 1984, the government and its corporate spies now watch our every move.

Much like Huxley’s A Brave New World, we are churning out a society of watchers who “have their liberties taken away from them, but … rather enjoy it, because they [are] distracted from any desire to rebel by propaganda or brainwashing.”

Much like Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, the populace is now taught to “know their place and their duties, to understand that they have no real rights but will be protected up to a point if they conform, and to think so poorly of themselves that they will accept their assigned fate and not rebel or run away.”

And in keeping with Philip K. Dick’s darkly prophetic vision of a dystopian police state—which became the basis for Steven Spielberg’s futuristic thriller Minority Report which was released 20 years ago—we are now trapped into a world in which the government is all-seeing, all-knowing and all-powerful, and if you dare to step out of line, dark-clad police SWAT teams and pre-crime units will crack a few skulls to bring the populace under control.

Minority Report is set in the year 2054, but it could just as well have taken place in 2022.

Seemingly taking its cue from science fiction, technology has moved so fast in the short time since Minority Report premiered in 2002 that what once seemed futuristic no longer occupies the realm of science fiction.

Incredibly, as the various nascent technologies employed and shared by the government and corporations alike—facial recognition, iris scanners, massive databases, behavior prediction software, and so on—are incorporated into a complex, interwoven cyber network aimed at tracking our movements, predicting our thoughts and controlling our behavior, Spielberg’s unnerving vision of the future is fast becoming our reality.

Both worlds—our present-day reality and Spielberg’s celluloid vision of the future—are characterized by widespread surveillance, behavior prediction technologies, data mining, fusion centers, driverless cars, voice-controlled homes, facial recognition systems, cybugs and drones, and predictive policing (pre-crime) aimed at capturing would-be criminals before they can do any damage.

Surveillance cameras are everywhere. Government agents listen in on our telephone calls and read our emails. Political correctness—a philosophy that discourages diversity—has become a guiding principle of modern society.

The courts have shredded the Fourth Amendment’s protections against unreasonable searches and seizures. In fact, SWAT teams battering down doors without search warrants and FBI agents acting as a secret police that investigate dissenting citizens are common occurrences in contemporary America.

We are increasingly ruled by multi-corporations wedded to the police state. Much of the population is either hooked on illegal drugs or ones prescribed by doctors. And bodily privacy and integrity has been utterly eviscerated by a prevailing view that Americans have no rights over what happens to their bodies during an encounter with government officials, who are allowed to search, seize, strip, scan, spy on, probe, pat down, taser, and arrest any individual at any time and for the slightest provocation.

All of this has come about with little more than a whimper from an oblivious American populace largely comprised of nonreaders and television and internet zombies, but we have been warned about such an ominous future in novels and movies for years.

The following 15 films may be the best representation of what we now face as a society.

Fahrenheit 451 (1966). Adapted from Ray Bradbury’s novel and directed by Francois Truffaut, this film depicts a futuristic society in which books are banned, and firemen ironically are called on to burn contraband books—451 Fahrenheit being the temperature at which books burn. Montag is a fireman who develops a conscience and begins to question his book burning. This film is an adept metaphor for our obsessively politically correct society where virtually everyone now pre-censors speech. Here, a brainwashed people addicted to television and drugs do little to resist governmental oppressors.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). The plot of Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece, as based on an Arthur C. Clarke short story, revolves around a space voyage to Jupiter. The astronauts soon learn, however, that the fully automated ship is orchestrated by a computer system—known as HAL 9000—which has become an autonomous thinking being that will even murder to retain control. The idea is that at some point in human evolution, technology in the form of artificial intelligence will become autonomous and human beings will become mere appendages of technology. In fact, at present, we are seeing this development with massive databases generated and controlled by the government that are administered by such secretive agencies as the National Security Agency and sweep all websites and other information devices collecting information on average citizens. We are being watched from cradle to grave.

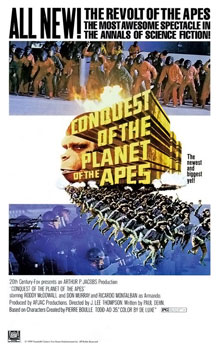

Planet of the Apes (1968). Based on Pierre Boulle’s novel, astronauts crash on a planet where apes are the masters and humans are treated as brutes and slaves. While fleeing from gorillas on horseback, astronaut Taylor is shot in the throat, captured and housed in a cage. From there, Taylor begins a journey wherein the truth revealed is that the planet was once controlled by technologically advanced humans who destroyed civilization. Taylor’s trek to the ominous Forbidden Zone reveals the startling fact that he was on planet earth all along. Descending into a fit of rage at what he sees in the final scene, Taylor screams: “We finally really did it. You maniacs! You blew it up! Damn you.” The lesson is obvious, but will we listen? The script, although rewritten, was initially drafted by Rod Serling and retains Serling’s Twilight Zone-ish ending.

THX 1138 (1970). George Lucas’ directorial debut, this is a somber view of a dehumanized society totally controlled by a police state. The people are force-fed drugs to keep them passive, and they no longer have names but only letter/number combinations such as THX 1138. Any citizen who steps out of line is quickly brought into compliance by robotic police equipped with “pain prods”—electro-shock batons. Sound like tasers?

A Clockwork Orange (1971). Director Stanley Kubrick presents a future ruled by sadistic punk gangs and a chaotic government that cracks down on its citizens sporadically. Alex is a violent punk who finds himself in the grinding, crushing wheels of injustice. This film may accurately portray the future of western society that grinds to a halt as oil supplies diminish, environmental crises increase, chaos rules, and the only thing left is brute force.

Soylent Green (1973). Set in a futuristic overpopulated New York City, the people depend on synthetic foods manufactured by the Soylent Corporation. A policeman investigating a murder discovers the grisly truth about what soylent green is really made of. The theme is chaos where the world is ruled by ruthless corporations whose only goal is greed and profit. Sound familiar?

Blade Runner (1982). In a 21st century Los Angeles, a world-weary cop tracks down a handful of renegade “replicants” (synthetically produced human slaves). Life is now dominated by mega-corporations, and people sleepwalk along rain-drenched streets. This is a world where human life is cheap, and where anyone can be exterminated at will by the police (or blade runners). Based upon a Philip K. Dick novel, this exquisite Ridley Scott film questions what it means to be human in an inhuman world.

Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984). The best adaptation of Orwell’s dark tale, this film visualizes the total loss of freedom in a world dominated by technology and its misuse, and the crushing inhumanity of an omniscient state. The government controls the masses by controlling their thoughts, altering history and changing the meaning of words. Winston Smith is a doubter who turns to self-expression through his diary and then begins questioning the ways and methods of Big Brother before being re-educated in a most brutal fashion.

Brazil (1985). Sharing a similar vision of the near future as 1984 and Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial, this is arguably director Terry Gilliam’s best work, one replete with a merging of the fantastic and stark reality. Here, a mother-dominated, hapless clerk takes refuge in flights of fantasy to escape the ordinary drabness of life. Caught within the chaotic tentacles of a police state, the longing for more innocent, free times lies behind the vicious surface of this film.

They Live (1988). John Carpenter’s bizarre sci-fi social satire action film assumes the future has already arrived. John Nada is a homeless person who stumbles across a resistance movement and finds a pair of sunglasses that enables him to see the real world around him. What he discovers is a world controlled by ominous beings who bombard the citizens with subliminal messages such as “obey” and “conform.” Carpenter manages to make an effective political point about the underclass—that is, everyone except those in power. The point: we, the prisoners of our devices, are too busy sucking up the entertainment trivia beamed into our brains and attacking each other up to start an effective resistance movement.

The Matrix (1999). The story centers on a computer programmer Thomas A. Anderson, secretly a hacker known by the alias “Neo,” who begins a relentless quest to learn the meaning of “The Matrix”—cryptic references that appear on his computer. Neo’s search leads him to Morpheus who reveals the truth that the present reality is not what it seems and that Anderson is actually living in the future—2199. Humanity is at war against technology which has taken the form of intelligent beings, and Neo is actually living in The Matrix, an illusionary world that appears to be set in the present in order to keep the humans docile and under control. Neo soon joins Morpheus and his cohorts in a rebellion against the machines that use SWAT team tactics to keep things under control.

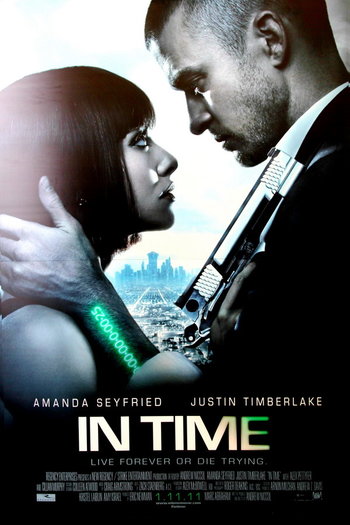

Minority Report (2002). Based on a short story by Philip K. Dick and directed by Steven Spielberg, the film offers a special effect-laden, techno-vision of a futuristic world in which the government is all-seeing, all-knowing and all-powerful. And if you dare to step out of line, dark-clad police SWAT teams will bring you under control. The setting is 2054 where PreCrime, a specialized police unit, apprehends criminals before they can commit the crime. Captain Anderton is the chief of the Washington, DC, PreCrime force which uses future visions generated by “pre-cogs” (mutated humans with precognitive abilities) to stop murders. Soon Anderton becomes the focus of an investigation when the precogs predict he will commit a murder. But the system can be manipulated. This film raises the issue of the danger of technology operating autonomously—which will happen eventually if it has not already occurred. To a hammer, all the world looks like a nail. In the same way, to a police state computer, we all look like suspects. In fact, before long, we all may be mere extensions or appendages of the police state—all suspects in a world commandeered by machines.

V for Vendetta (2006). This film depicts a society ruled by a corrupt and totalitarian government where everything is run by an abusive secret police. A vigilante named V dons a mask and leads a rebellion against the state. The subtext here is that authoritarian regimes through repression create their own enemies—that is, terrorists—forcing government agents and terrorists into a recurring cycle of violence. And who is caught in the middle? The citizens, of course. This film has a cult following among various underground political groups such as Anonymous, whose members wear the same Guy Fawkes mask as that worn by V.

Children of Men (2006). This film portrays a futuristic world without hope since humankind has lost its ability to procreate. Civilization has descended into chaos and is held together by a military state and a government that attempts to keep its totalitarian stronghold on the population. Most governments have collapsed, leaving Great Britain as one of the few remaining intact societies. As a result, millions of refugees seek asylum only to be rounded up and detained by the police. Suicide is a viable option as a suicide kit called Quietus is promoted on billboards and on television and newspapers. But hope for a new day comes when a woman becomes inexplicably pregnant.

Land of the Blind (2006). In this dark political satire, tyrannical rulers are overthrown by new leaders who prove to be just as evil as their predecessors. Maximilian II is a demented fascist ruler of a troubled land named Everycountry who has two main interests: tormenting his underlings and running his country’s movie industry. Citizens who are perceived as questioning the state are sent to “re-education camps” where the state’s concept of reality is drummed into their heads. Joe, a prison guard, is emotionally moved by the prisoner and renowned author Thorne and eventually joins a coup to remove the sadistic Maximilian, replacing him with Thorne. But soon Joe finds himself the target of the new government.

All of these films—and the writers who inspired them—understood what many Americans, caught up in their partisan, flag-waving, zombified states, are still struggling to come to terms with: that there is no such thing as a government organized for the good of the people. Even the best intentions among those in government inevitably give way to the desire to maintain power and control at all costs.

Eventually, as I make clear in my book Battlefield America: The War on the American People and in its fictional counterpart The Erik Blair Diaries, even the sleepwalking masses (who remain convinced that all of the bad things happening in the police state—the police shootings, the police beatings, the raids, the roadside strip searches—are happening to other people) will have to wake up.

Sooner or later, the things happening to other people will start happening to us.

When that painful reality sinks in, it will hit with the force of a SWAT team crashing through your door, a taser being aimed at your stomach, and a gun pointed at your head. And there will be no channel to change, no reality to alter, and no manufactured farce to hide behind.

As George Orwell warned, “If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face forever.”