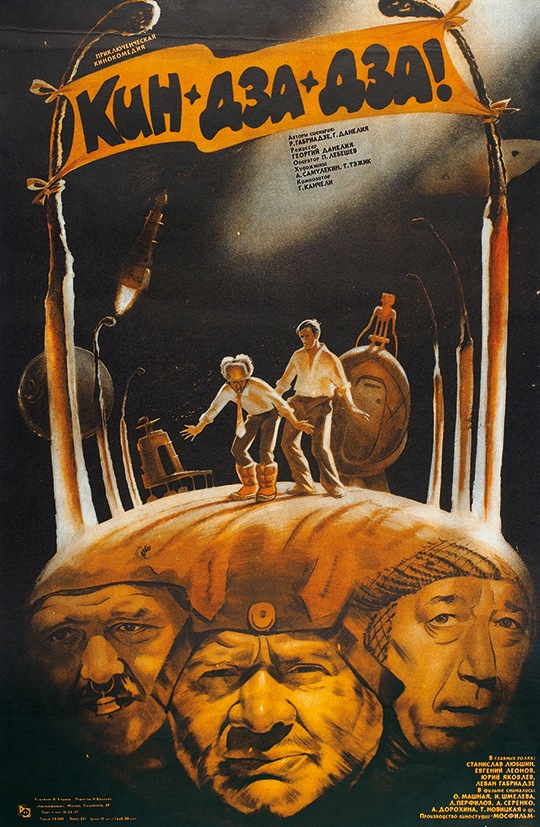

In praise of Kin-dza-dza! – the best sci-fi film you’ve never heard of

Mad Max meets Monty Python is the best way of describing this strange Soviet gem.

By Joel Blackledge

Source: Little White Lies

Originally released in 1986, Georgiy Daneliya’s Kin-dza-dza! is possibly the most underrated science fiction film of the past 50 years. A Soviet space odyssey across an alien landscape, it is packed with comic nuance and absurdist charm, yet it is rarely screened or even seen outside Russia. With 2016 marking its 30th anniversary, this deadpan oddity deserves a reappraisal for its wit, imagination and stunning design.

The story begins with Vladimir, a Moscow construction worker, popping out for some macaroni. He is stopped in the street by Gedevan, a young student who needs help with a seemingly insane man claiming to be on the wrong planet. The man needs Earth’s coordinates so he can use his teleportation device to go home. Impatiently humouring him, Vladimir presses a button on the device. Instantly, he and Gedevan are transported to the desert planet Pluke in the galaxy of Kin-dza-dza.

Before long, they meet Bi and Wef, two wandering performers whose speech is largely limited to the word ‘koo’ or its vulgar equivalent ‘kyu’. The Earthlings haggle over the terms of their rescue, though the performers are loath to give something for nothing. Just as the performers are about to leave, they notice that Vladimir has a box of matches – one of the most valuable commodities on Pluke. The four establish a shaky alliance and set in off in a ramshackle aircraft to find a way back to Earth. Vladimir and Gedevan discover that the entire planet operates on a ruthless economy of scavenger barter, and nothing is off limits to the market. The deserts were once seas, but the water was greedily converted into engine fuel. Of course, now the only way to collect drinking water is to extract it back from that fuel.

Kin-dza-dza!’s salvage punk aesthetic – which might best be described as Mad Max meets Monty Python by way of Tarkovsky – hints at this rich, tragic and very stupid history. A collapsed Ferris wheel provides a home for destitute desert dwellers. Graves are marked by balloons containing the deceased’s final breath. The colour of your trousers signifies social status, so they are powerful barter items.

The planet’s inhabitants are primitive in their hardheartedness, yet they also fiercely insist upon maintaining arbitrary social conventions. People are separated into two castes: “Chatlian” and “Patsak”. The subordinate Patsaks must wear bells on their noses and squat before Chatlians. The only way to determine if an individual is a Patsak or a Chatlian is to see if a purpose-built machine emits a green or orange light when pointed at them. The Earthling visitors decry this as racism of the most inane kind, but Plukanians fail to see the problem. When Bi asks with genuine puzzlement how people on Earth determine who is subservient to whom, Vladimir dryly responds, ‘Oh, just by eye.’ Hearing this, Wef dismisses Earthlings as savages. Advanced technology does not a civilised culture make.

What elevates Kin-dza-dza! beyond a simple procession of snipes is the careful attention paid to countless details within its alien world. Even Giya Kancheli’s comic score sounds like it’s from another world – an ungainly, melancholic dirge that conjures up the hopeless bafflement of absurdism. All of this rich world building puts the film into a literary branch of satirical sci-fi occupied by the likes of Kurt Vonnegut, Douglas Adams, and even Franz Kafka. There is no convoluted plot, but instead a convoluted universe, and its incredulous victims ready to point out the farcicality therein. They find a planet that demands a mix of callous entrepreneurial savvy and fearful deference to the status quo familiar to any Earthling living in the 21st century.

Kin-dza-dza!’s sideways look at the barbarities of everyday oppression remains pertinent 30 years on. It’s a must-see for anyone interested in the cosmic potentials of science fiction.

Watch Kin-dza-dza! on Kanopy here: https://www.kanopy.com/en/product/14715372