By Dr. Joseph Mercola

Source: The Herland Report

Who Owns the World? A handful of mega corporations — private investment companies — dominate every aspect of our lives; everything we eat, drink, wear or use in one way or another.

These investment firms are so enormous, they control the money flow worldwide.

While there appear to be hundreds of competing brands on the market, like Russian nesting dolls, larger parent companies own multiple smaller brands. In reality, all packaged food brands, for example, are owned by a dozen or so larger parent companies. (Feature photo: A rare photo of The Federal Reserve Board of Governors)

These parent companies, in turn, are owned by shareholders, and the largest shareholders are the same in all of them: Vanguard and Blackrock, writes Dr. Joseph Mercola, osteopathic physician, best-selling author and recipient of multiple awards in the field of natural health.

No matter what industry you look at, the top shareholders, and therefore decision makers, are the same: Vanguard, Blackrock, State Street and/or Berkshire Hathaway. In virtually every major company, you find these names among the top 10 institutional investors.

These major investment firms are in turn owned by their own set of shareholders. One of the most amazing things about this scheme is that the institutional investors also own each other.

They’re all shareholders in each other’s companies. At the very top are Vanguard and Blackrock. Blackrock’s largest shareholder is Vanguard, which does not disclose the identity of its shareholders due to its unique structure.

To understand what’s really going on, watch Tim Gielen’s hour-long documentary, “MONOPOLY: Who Owns the World?”

Who Owns the World? Until recently, it appeared economic competition had been driving the rise and fall of small and large companies across the U.S. Supposedly, PepsiCo is Coca Cola’s competitor, Apple and Android vie for your loyalty and drug companies battle for your health care dollars. However, all of that turns out to be an illusion.

Since the mid-1970s, two corporations — Vanguard and Blackrock — have gobbled up most companies in the world, effectively destroying the competitive market on which America’s strength has rested, leaving only false appearances behind.

Indeed, the global economy may be the greatest illusionary trick ever pulled over the eyes of people around the world. To understand what’s really going on, watch Tim Gielen’s hour-long documentary, “MONOPOLY: Who Owns the World?” above.

Corporate Domination

Who Owns the World? As noted by Gielen, who narrates the film, a handful of mega corporations — private investment companies — dominate every aspect of our lives; everything we eat, drink, wear or use in one way or another. These investment firms are so enormous, they control the money flow worldwide. So, how does this scheme work?

While there appear to be hundreds of competing brands on the market, like Russian nesting dolls, larger parent companies own multiple smaller brands. In reality, all packaged food brands, for example, are owned by a dozen or so larger parent companies.

Pepsi Co. owns a long list of food, beverage and snack brands, as does Coca-Cola, Nestle, General Mills, Kellogg’s, Unilever, Mars, Kraft Heinz, Mondelez, Danone and Associated British Foods. Together, these parent companies monopolize the packaged food industry, as virtually every food brand available belongs to one of them.

These companies are publicly traded and are run by boards, where the largest shareholders have power over the decision making. This is where it gets interesting, because when you look up who the largest shareholders are, you find yet another monopoly.

While the topmost shareholders can change from time to time, based on shares bought and sold, two companies are consistently listed among the top institutional holders of these parent companies: The Vanguard Group Inc. and Blackrock Inc.

Pepsi and Coca-Cola — An Example

Who Owns the World? For example, while there are more than 3,000 shareholders in Pepsi Co., Vanguard and Blackrock’s holdings account for nearly one-third of all shares. Of the top 10 shareholders in Pepsi Co., the top three, Vanguard, Blackrock and State Street Corporation, own more shares than the remaining seven.

Now, let’s look at Coca-Cola Co., Pepsi’s top competitor. Who owns Coke? As with Pepsi, the majority of the company shares are held by institutional investors, which number 3,155 (as of the making of the documentary).

As shown in the film, three of the top four institutional shareholders of Coca-Cola are identical with that of Pepsi: Vanguard, Blackrock and State Street Corporation. The No. 1 shareholder of Coca-Cola is Berkshire Hathaway Inc.

These four — Vanguard, Blackrock, State Street and Berkshire Hathaway — are the four largest investment firms on the planet. “So, Pepsi and Coca-Cola are anything but competitors,” Gielen says. And the same goes for the other packaged food companies. All are owned by the same small group of institutional shareholders.

Big Tech Monopoly

Who Owns the World? The monopoly of these investment firms isn’t relegated to the packaged food industry. You find them dominating virtually all other industries as well. Take Big Tech, for example. Among the top 10 largest tech companies we find Apple, Samsung, Alphabet (parent company of Google), Microsoft, Huawei, Dell, IBM and Sony.

Here, we find the same Russian nesting doll setup. For example, Facebook owns Whatsapp and Instagram. Alphabet owns Google and all Google-related businesses, including YouTube and Gmail.

It’s also the biggest developer of Android, the main competitor to Apple. Microsoft owns Windows and Xbox. In all, four parent companies produce the software used by virtually all computers, tablets and smartphones in the world. Who, then, owns them? Here’s a sampling:

- Facebook — More than 80% of Facebook shares are held by institutional investors, and the top institutional holders are the same as those found in the food industry: Vanguard and Blackrock being the top two, as of the end of March 2021. State Street Corporation is the fifth biggest shareholder

- Apple — The top four institutional investors are Vanguard, Blackrock, Berkshire Hathaway and State Street Corporation

- Microsoft — The top three institutional shareholders are Vanguard, Blackrock and State Street Corporation

You can continue going through the list of tech brands — companies that build computers, smart phones, electronics and household appliances — and you’ll repeatedly find Vanguard, Blackrock, Berkshire Hathaway and State Street Corporation among the top shareholders.

Same Small Group Owns Everything Else Too

Who Owns the World? The same ownership trend exists in all other industries. Gielen offers yet another example to prove this statement is not an exaggeration:

“Let’s say we want to plan a vacation. On our computer or smart phone, we look for a cheap flight to the sun through websites like Skyscanner and Expedia, both of which are owned by the same group of institutional investors [Vanguard, Blackrock and State Street Corporation].

We fly with one of the many airlines [American Airlines, Air France, KLM, United Airlines, Delta and Transavia] of which the majority of the shares are often owned by the same investors …

The airline we fly [on] is in most cases a Boeing or an Airbus. Again, we see the same [institutional shareholders]. We look for a hotel or an apartment through Bookings.com or AirBnB.com. Once we arrive at our destination, we go out to dinner and we write a review on Trip Advisor. The same investors are at the basis of every aspect of our journey.

And their power goes even much further, because even the kerosene that fuels the plane comes from one of their many oil companies and refineries. Just like the steel that the plane is made of comes from one of their many mining companies.

This small club of investment companies, banks and mutual funds, are also the largest shareholders in the primary industries, where our raw materials come from.”

The same goes for the agricultural industry that the global food industry depends on, and any other major industry. These institutional investors own Bayer, the world’s largest seed producer; they own the largest textile manufacturers and many of the largest clothing companies.

They own the oil refineries, the largest solar panel producers and the automobile, aircraft and arms industries. They own all the major tobacco companies, and all the major drug companies and scientific institutes too. They also own the big department stores and the online marketplaces like eBay, Amazon and AliExpress.

They even own the payment methods we use, from credit card companies to digital payment platforms, as well as insurance companies, banks, construction companies, telephone companies, restaurant chains, personal care brands and cosmetic brands.

No matter what industry you look at, the top shareholders, and therefore decision makers, are the same: Vanguard, Blackrock, State Street and/or Berkshire Hathaway. In virtually every major company, you find these names among the top 10 institutional investors.

Who Owns the Investment Firms of the World?

Who Owns the World? Diving deeper, we find that these major investment firms are in turn owned by their own set of shareholders. One of the most amazing things about this scheme is that the institutional investors — and there are many more than the primary four we’ve focused on here — also own each other. They’re all shareholders in each other’s companies.At the top of the pyramid — the largest Russian doll of all — we find Vanguard and Blackrock.

“Together, they form an immense network that we can compare to a pyramid,” Gielen says. Smaller institutional investors, such as Citibank, ING and T. Rowe Price, are owned by larger investment firms such as Northern Trust, Capital Group, 3G Capital and KKR.

Those investors in turn are owned by even larger investment firms, like Goldman Sachs and Wellington Market, which are owned by larger firms yet, such as Berkshire Hathaway and State Street. At the top of the pyramid — the largest Russian doll of all — we find Vanguard and Blackrock.

“The power of these two companies is something we can barely imagine,” Gielen says. “Not only are they the largest institutional investors of every major company on earth, they also own the other institutional investors of those companies, giving them a complete monopoly.”

Gielen cites data from Bloomberg, showing that by 2028, Vanguard and BlackRock are expected to collectively manage $20 trillion-worth of investments. In the process, they will own almost everything on planet Earth.

BlackRock — The Fourth Branch of Government

Who Owns the World? Bloomberg has also referred to BlackRock as the “fourth branch of government,” due to its close relationship with the central banks. BlackRock actually lends money to the central bank, the federal reserve, and is their principal adviser.

Dozens of BlackRock employees have held senior positions in the White House under the Bush, Obama and Biden administrations. BlackRock also developed the computer system that the central banks use.

While Larry Fink is the figurehead of BlackRock, being its founder, chairman and chief executive officer, he’s not the sole decision maker, as BlackRock too is owned by shareholders. Here we find yet another curiosity, as the largest shareholder of BlackRock is Vanguard.

Who Owns the World? “This is where it gets dark,” Gielen says. Vanguard has a unique structure that blocks us from seeing who the actual shareholders are. “The elite who own Vanguard don’t want anyone to know they are the owners of the most powerful company on earth.” Still, if you dig deep enough, you can find clues as to who these owners are.

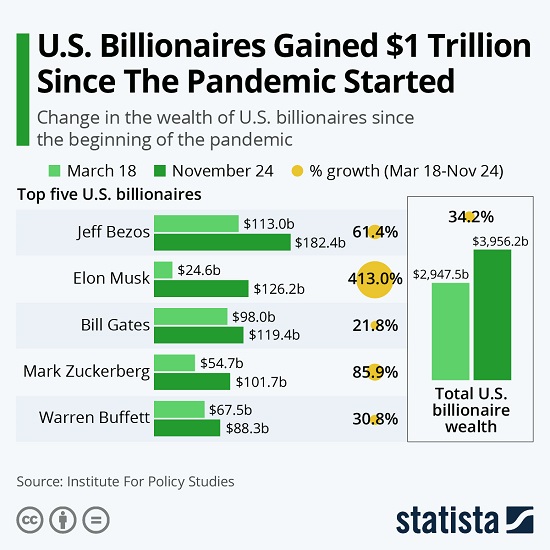

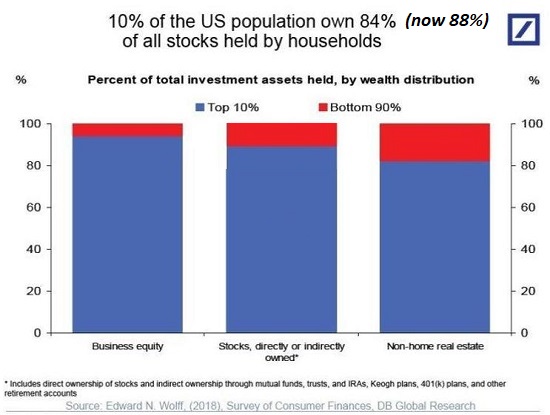

The owners of the wealthiest, most powerful company on Earth can be expected to be among the wealthiest individuals on earth. In 2016, Oxfam reported that the combined wealth of the richest 1% in the world was equal to the wealth of the remaining 99%. In 2018, it was reported that the world’s richest people get 82% of all the money earned around the world in 2017.

In reality, we can assume that the owners of Vanguard are among the 0.001% richest people on the planet. According to Forbes, there were 2,075 billionaires in the world as of March 2020. Gielen cites Oxfam data showing that two-thirds of billionaires obtained their fortunes via inheritance, monopoly and/or cronyism.

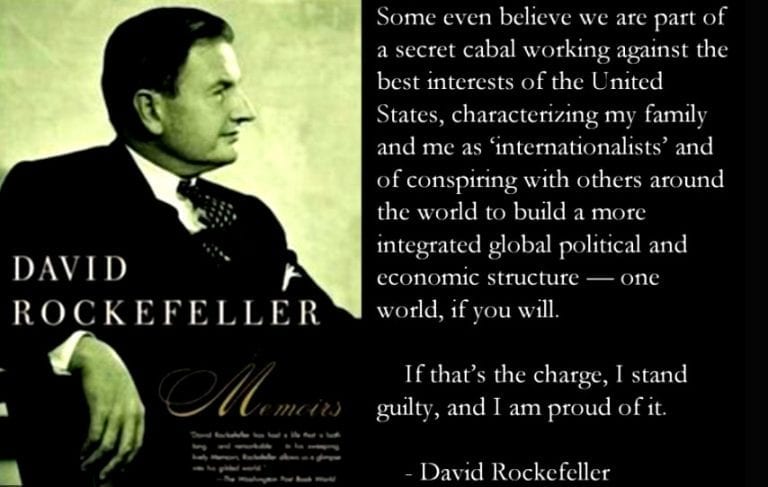

“This means that Vanguard is in the hands of the richest families on earth,” Gielen says. Among them we find the Rothschilds, the DuPont family, the Rockefellers, the Bush family and the Morgan family, just to name a few.

Many belong to royal bloodlines and are the founders of our central banking system, the United Nations and just about every industry on the planet.

Gielen goes even further in his documentary, so I highly recommend watching it in its entirety. I’ve only summarized a small piece of the whole film here.

A Financial Coup D’etat

Speaking of the central bankers, I recently interviewed finance guru Catherine Austin Fitts, and she believes it’s the central bankers that are at the heart of the global takeover we’re currently seeing. She also believes they are the ones pressuring private companies to implement the clearly illegal COVID jab mandates. Their control is so great, few companies have the ability to take a stand against them.

“I think [the central bankers] are really depending on the smart grid and creepy technology to help them go to the last steps of financial control, which is what I think they’re pushing for,” she said.

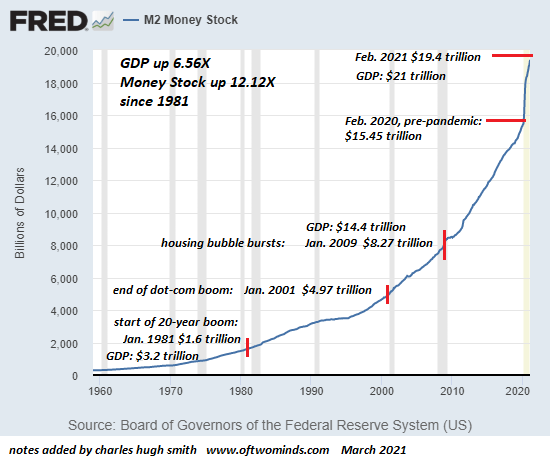

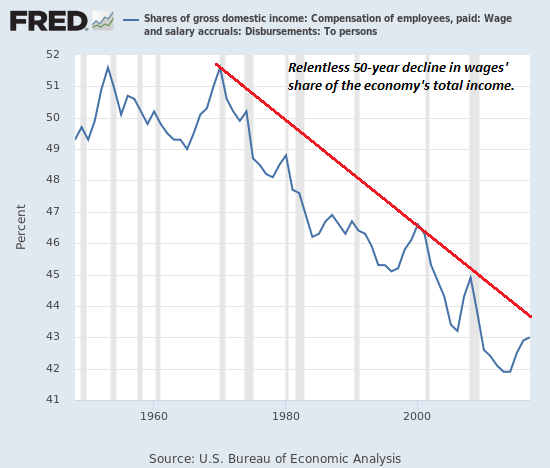

“What we’ve seen is a tremendous effort to bankrupt the population and the governments so that it’s much easier for the central bankers to take control. That’s what I’ve been writing about since 1998, that this is a financial coup d’etat.

Now the financial coup d’etat is being consolidated, where the central bankers just serve jurisdiction over the treasury and the tax money. And if they can get the [vaccine] passports in with the CBDC [central bank digital currency], then it will be able to take taxes out of our accounts and take our assets. So, this is a real coup d’etat.”