Is our expansive evolution in technological advancement a wrong turn for humanity? Or has it evolved without our consciousness keeping up to steward it effectively?

By Tom Bunzel

Source: The Pulse

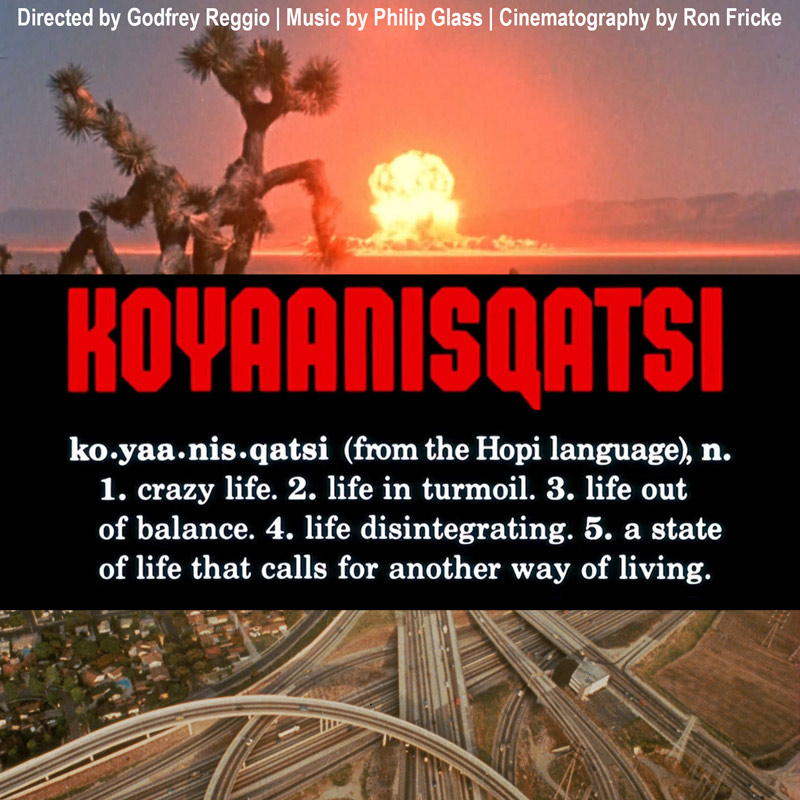

One of my first really disquieting insights about the planet and the pace of change came when I saw the film “World Out of Balance” or “Koyaanisqatsi” in the 1980’s.

The concept behind the film was that Nature has an exquisite balance between various forces, and that’s when I first thought about the likelihood of the existence of a higher intelligence.

The film was jarring because it showed dramatically, now 40 plus years ago, the havoc that was wreaked by technology not just on the environment, but how human technology was literally putting the world out of balance – a harmony that was naturally sustained prior to human intervention.

Computers Introduced Me to Rapid Change

At that time, I just getting interested in computer graphics and I encountered “Moore’s Law”, which refers to the observation made by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore in 1965 that the number of transistors on integrated circuits doubles approximately every two years.

That meant that processing power doubled in the same span of time, allowing graphics, for example, to go from color, to 3D, to 3D with texture mapping and other effects, and on and on.

One example of this was the original movie Jurassic Park, which was made with 3D models of dinosaurs having their wire frames “texture mapped” – covered with skin and then animated on a Silicon Graphics work station. The processing power required to render these images quickly enough for a 30 frames per second film was staggering.

I just Googled the company. As I suspected they are extinct like the dinosaurs; and the process I described above now happens on a phone, or on a website, and films are using artificial intelligence to fool audiences.

As I began writing about digital video and animation, and attended conferences, I found myself on a carousel of a continual need to adapt to change, and “upgrade” my system to keep up with the latest advancements.

It worked for me for a while and I enjoyed integrating solutions based on a creative understanding of what was coming out, but eventually, I realized that I could no longer keep up.

I had to take a break from the relentless pressure, which I did, and ended my tech writing career.

It was around that time I was reading Eckhart Tolle, and learning how the Ego, the voice in my head, always wants MORE.

The Continued Acceleration of Change

Moore’s law for integrated circuits was only the beginning, of course. We now have the promise of quantum computing and the reality of artificial intelligence, which both have the potential to put the world as we knew it even more out of balance.

When we consider our human conditioning, the wider the gap between one’s childhood where one “learns the ropes” and perhaps conforms for one’s safety and one’s adulthood — when everything has changed creates intense discomfort relative to the gap in years.

For a dinosaur like me the continual need to “download the app” is stressful. For my friends’ grandchildren it’s just part of being alive.

Peter Russell, in his new book “Forgiving Humanity” uses a sobering term – Exponential Change – as he describes how rapid changes in technology first affected agrarian culture, increased dramatically with the industrial revolution and accelerated again with the advent of computer technology and integrated circuits.

It’s Not You, It’s Exponential Change

He reaches a conclusion that is both profound and daunting:

“This doesn’t mean humankind has taken a wrong turn. Spiraling rates of development, with all their consequences, positive and negative, are the inevitable destiny of any intelligent, technologically-empowered species.”

So the fact that we have knocked the world out of its natural harmony is something that is part of evolution? In essence, we are a part of nature that keeps pushing the envelope, but it can have dire consequences for a species that goes too far?

That is certainly what we are up against with respect to artificial intelligence, where the notion of exponential change in terms of brute intellectual capacity, is making many experts wary of consequences of an “intelligence” that vastly dwarfs human capabilities.

Consider the difference between exponential change versus simple, let us say, incremental change. Exponential means that is multiplied by its current value, or the power of 2. Anyone who has played with relationships like that in math knows how rapidly it can spin out of control.

Calculations of this order of magnitude quickly go beyond what the human brain can process.

And how does this expansion of potential knowledge affect consciousness today?

Peter Russell takes one of the driving forces of exponential change – AI – and discusses his new book by interviewing “his clone” in a fascinating video.

There is the possibility that with enough shocks or consequences that humanity may begin to glean that a purely intellectual approach to reality is the reason for our imbalance, and that knowledge itself, without wisdom or “being”, is fraught with peril. Blind intellect alone creates conflict with a higher, natural intelligence which it ignores.

Russell uses the analogy of how a wheel that spins faster and faster will eventually come apart.

Taking a Cosmic Perspective – Collectively and Individually

In the video Russell’s “clone” suggests that a way for humanity to adapt, and actually align with the natural forces that have brought it to this point, is to begin to take a truly “cosmic perspective” and see our species in true proportion to the vast universe in which we now find ourselves.

Advances like the Webb Telescope have opened humanity’s eyes to a more accurate understanding of the vast scale of the universe we inhabit. We now know that galaxies move in clusters of unimaginable proportions.

Russell points out that there are trillions of stars and life might have evolved to an intelligent level on some of these, and that perhaps such life has found itself at the point where we are many times in eternity.

We have to confront the stark reality that from such a perspective within the vastness of Nature, we are here for only a brief interval both as individuals – and indeed perhaps as a species.

Russell suggests that such a perspective can make us more aware and grateful for our higher capabilities in areas beyond the intellect, such as art, culture, and probably philosophy. Humanity needs to become more deeply human once again rather than purely mental, as the computers we use are just brute intellect.

A Shift Beyond Copernican Proportions

Such a “renaissance” would be like a new Copernican revolution. Most of us have a perspective (in consciousness) that WE are the center of all existence.

But from a “cosmic” perspective we must recognize that cannot be true; it must be an illusion. We can begin by sensing the truth through our bodies that we are organic beings within dimensions of a vast organism (maybe like the microscopic organisms that exist in our gut and make our “lives” possible are organic beings within us) – and this recognition could serve to dampen both our hubris as a species as to how important we are (dominant on this planet), but also make this a cornerstone of a viable personal philosophy.

I don’t know if I will be here to witness it, but I sense that this shift is very much in line with current trends toward a more dramatic “Disclosure” of our place in the universe – revealing that several other interplanetary or interdimensional species have been here, communicated with humans and are still monitoring human affairs.

Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb, who gained prominence when he speculated that “Oumamoua” – the interstellar object spotted entering and leaving our solar system recently, showed that it was intelligently controlled. He has since begun Galileo project to search for evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence.

All of this is finally putting to rest the misgivings of the famous Brookings memo that greatly contributed to the secrecy around UFOs – the memo speculated that if extraterrestrial life were a proven reality many social structures, religions and institutions would collapse. Better to hush it up.

But of course, we are now witnessing the dissolution of many conditioned beliefs and the institutions that these flawed beliefs supported; among them our belief in our dominance as a species and our self-importance as individuals.

It would give me hope to see the shift completed with a deep comprehension of our connection to the universe both epigenetically and spiritually.