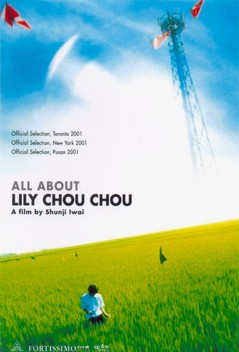

THE GRAY TRAGEDY OF YOUTH IN JAPAN: SHUNJI IWAI’S “ALL ABOUT LILY CHOU-CHOU”

By Luke Powell

Source: Sabukaru

Released in 2001, writer and director Shunji Iwai’s “All About Lily Chou-Chou” 「リリイ• シュシュのすべて」is a masterclass in complex and powerful storytelling, cinematography, and meta-textual messaging that puts on display the formative, introspective, and oftentimes malicious enigma that is the life of youth in Japan.

Set in the town of Ashikaga, the story centers around the relationship of two young boys, Shusuke Hoshino and Yuichi Hasumi, as they progress through junior high school. Hoshino is known to be one of the top students in their school and is harassed and ostracized by his classmates as a result, a commonplace occurrence for those caught outside the boundaries of conformity while growing up in Japan. Yuichi, in contrast, is shy and submissive to the societal structures that surround him, only paying attention and devoting all his personal time to the singer and songwriter Lily Chou-Chou.

In his free time, Yuichi manages an online BBS chatroom titled “Lilyholic,” which is completely dedicated to Lily and her music, and the messages sent between users of this website overlay much of the film. The mystery surrounding this chatroom and the messages between its users acts as a crucial plot point that slowly unravels in conjunction with the film’s events.

At one point, Yuichi, Hoshino, and their friends manage to secure a trip to Okinawa, during which Hoshino has a near-death experience that serves as the foundation for the cruel and unusual monster that he becomes, changing his and Yuichi’s relationship forever as he usurps his way into being the school’s bully the following school year. Despite the title, this is not simply a story about a fictional songwriter and her music, but the disturbing and oftentimes glossed-over ways in which modern society corrupts the minds of youth, and the various ways those children attempt to cope against such odds.

Yuichi’s love and devotion for Lily Chou-Chou is the emotional epicenter of this film, as it displays the profound ability for music to save and give meaning to young people’s lives, especially when surrounded by ignorant adults and inhumane peers. While the musician herself is fictional, Lily Chou-Chou’s mythical music expands over the course of the film, overlaying its imagery of lonesomeness, isolation, and absurdity with luscious, calming, and poignant bits of melancholic bliss; a reflection of Yuichi’s character and perspective on the world around him.

Users of the chatroom “Lilyholic” continuously exclaim their love for Lily and her ability to channel the “Ether,” an invisible yet omni-present force that connects all fans of Lily Chou-Chou together in their existence through Lily’s music. The “Ether” is an intrinsic aspect of the power her music has on those who listen to her, serving as the connective thread that weaves its way through the fabric of a fragile reality, allowing those lost in the tribulations of life to hold onto something organic, warm, and personal, an oasis among a desert of expectations, conformity, and isolation.

It goes without saying that the music on display in this film is truly special and should be experienced firsthand, with the soundtrack growing organically as the audience learns more about Lily, her music, and the different characters in the film who become impacted by her compositions [for better or for worse].

Throughout the film, there are multiple references to the classical French composer Claude Debussy, whom users of Lilyholic cite as being one of Lily’s musical inspirations, as he was able to produce the “Ether” through his compositions. For example, the song that accompanies the opening scene of the film, titled 「アラベスク」[“Arabesuku”] is based off of Debussy’s “Arabesque No. 1.” Lily’s shrill yet comforting voice glides over synthesized piano chords, distanced hints of strained guitar, and a lo-fi drum beat that subjects the 19th-century classical work to a cybernetic restructuring – all of which results in one of the most captivating opening experiences in film.

Arranged and produced by Takeshi Kobayashi, the music of “All About Lily Chou-Chou” is a kaleidoscope of sonic captivity, melting between Lily’s somber yet grungy aesthetic as well as moments of clarity through the use of classical composers like Debussy, combining to create less of a soundtrack and more of an experience that will cling to you long after the credits have finished rolling.

The narrative direction and cinematography of “All About Lily Chou-Chou” are also aspects that cannot be ignored. The narrative’s timeline is fractured, starting chronologically from the middle of the story, eventually flashing back to the canonical beginning, and finally returning to the present to finish out the film. The script is adapted from an online novel that was written by director Shunji Iwai himself in the chatroom of a real-life version of the “Lilyholic” website, in which the director plays out the story of “All About Lily Chou-Chou” through the chat exchanges of two site users. A version of this website can still be accessed online today, and its existence is only the tip of the iceberg for the extensive material surrounding this film beyond its screen time. The narrative, in this sense, is multi-layered and meta-textual – an interactive and organic experience that not only goes beyond the medium of film but places a sense of participation and influence in the viewer, only to be powerless against the fierce, apathetic, and surreal scenes we witness.

The cinematography by Noboru Shinoda [“Hana and Alice,” “Love Letter”] is just as varied and complex as the film’s narrative, as it switches between ethereal, lush views of rice fields and angelic classroom settings in one shot, to the jarring use of hand-held cameras and disorienting angles in the next. Shinoda and Iwai were the first Japanese filmmakers to use the now discontinued Sony HDW-F900 digital video camera which was designed to reflect the look of 35mm film, further emphasizing the thematic imagery of nostalgia and dream-like isolation.

The camera work almost seems to be shot by a child at times, such as an unseen member of Yuichi’s friend group or class as they youthfully document the strange and disturbing events occurring in front of them, only focusing on the power a digital camera has without considering what they are actually recording. Or rather, Iwai may be intending for us, the viewer, to put ourselves behind the lens, acting as a silent observer to the events that unfold without the voice or power to do anything about it, which is strikingly similar to Yuichi’s character in the film itself. The combination of a fractal narrative structure and an abrasive yet realistic use of the camera encapsulates so much of the themes and messaging this film has to offer – mainly that being the confusing, frustrating, and unapologetic nature of growing up surrounded by unforgiving societal structures, while at the same time blindly attempting to hold onto and bask in the naiveté of youth.

The subject of youth is the eye of Iwai’s proverbial hurricane of emotion and turmoil that is “All About Lily Chou-Chou.” Made in 2001, this film was produced at a time in Japan that saw a sharp increase in teenage crime and suicide following the economic collapse of 1991. In a country so wrought with societal and familial expectations, the bursting of their economic bubble proved disastrous for Japan’s teenage and young-adult population, as they were now tasked with bearing said expectations and cultural conformity against a historically low employment rate.

Commonly referred to as the “Lost Decade,” the 1990s in Japan was filled with headlines detailing the effect of the recession on the country’s young population, as teenage crime doubled in frequency, and reports of bullying and assault within schools skyrocketed. The rise in crime and disillusionment among the country’s youth resulted in many Japanese filmmakers attempting to grasp this idea of “teenage rage” through their films in the late 90s and early 2000s, such as in Takashi Miike’s “Fudoh: The New Generation” [1996] and Kinji Fukasaku’s “Battle Royale” [2000]. While these films painted a more dystopian and fantastical perspective of the violent phenomenon, Shunji Iwai wanted to represent this general angst and discontent in a more realistic manner that would directly connect with the audience it sought to portray. In one interview from 1995, Iwai reflects on his perspective towards the children who will be watching his stories: “We have to make movies that appeal to them and reflect the world they live in.”

The characters within “All About Lily Chou-Chou” represent the cruel realities of the “Lost Decade.” They don’t conduct acts of headline-defining mass crime or comical absurdity, but instead are portrayed as unheard, misguided, and tragic children who are following in the steps of complicit adults as they attempt to find answers in a confusing world that they have no power in controlling. As shown in the film, some of these characters choose to find those answers in disturbing cruelty or abusive domination over their peers, while others try to be as passive or silent as humanly possible just to survive. And yet, while each character within this film leads a complex and difficult life that sometimes results in catastrophe, all of them are connected through the “Ether,” endlessly searching for a sense of comfort, acceptance, and understanding through the soundscape of Lily Chou-Chou. It could be said that the characters within this film are all living in, as Yuichi states in one monologue, “the age of Gray,” a liminal space of reality that seems to place their lives in a state of constant immobility and pain. Life is made void of color by the brutal violence and betrayal that these children either commit or fall victim to, and for some, Lily provides safety and guidance in that darkness, while she may also fuel the angry, merciless fire burning inside others.

“All About Lily Chou-Chou” is dark, disturbing, and cruel in its presentation, but manages to be something so much more intimate, profound, and human in its substance. It discusses themes surrounding the troubles of youth in Japan, who are constantly cornered by cultural and familial expectations, conformity, and a social hierarchy that can be detrimental to those caught in its jaws. It portrays the fragility of youth, how easily corruptible a young mind can be, and how one source of bliss can be enough to hold onto the hope of a better tomorrow. Today, in a world dominated by online interactions, superficial connections, and an uncertain future, this film is more relevant than ever before – a true cyber hymn that anyone and everyone can find meaning within.

We have attached the album that was released under the name “Lily Chou-Chou” after the movie was released so that you can get a better feel for the movie and the artist that is the titular character of the entire film. It features all of Lily’s music that is present in the film, and is titled “Kokyu” [or “Breathe” in English], which is in reference to the project that she released during the movie itself.

The entire thing can also be streamed on Spotify. In particular, the following songs are absolutely stunning and very representative of the movie itself:

- Arabesque [アラベスク “Arabesuku”]

- Flightless Wings [飛べない翼 “Tobenai Tsubasa”]

- Glide [グライド “Guraido”]

Watch All About Lily Chou Chou on Kanopy here: https://www.kanopy.com/en/product/5636535