By Seymour Hersh

Source: Mint Press News

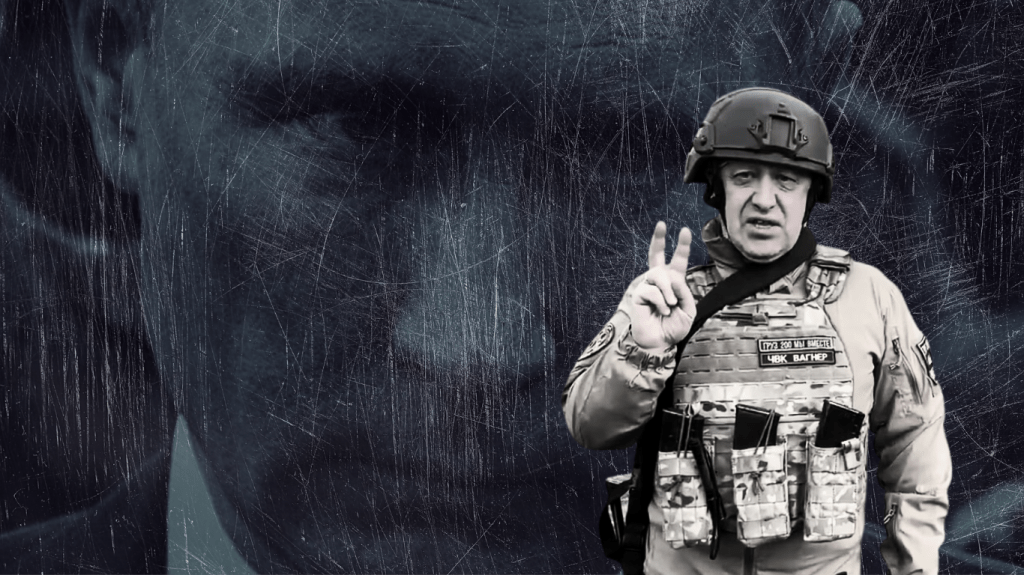

The Biden administration had a glorious few days last weekend. The ongoing disaster in Ukraine slipped from the headlines to be replaced by the “revolt,” as a New York Times headline put it, of Yevgeny Prigozhin, chief of the mercenary Wagner Group.

The focus slipped from Ukraine’s failing counter-offensive to Prigozhin’s threat to Putin’s control. As one headline in the Times put it, “Revolt Raises Searing Question: Could Putin Lose Power?” Washington Post columnist David Ignatius posed this assessment: “Putin looked into the abyss Saturday—and blinked.”

Secretary of State Antony Blinken—the administration’s go-to wartime flack, who weeks ago spoke proudly of his commitment not to seek a ceasefire in Ukraine—appeared on CBS’s Face the Nation with his own version of reality: “Sixteen months ago, Russian forces were . . . thinking they would erase Ukraine from the map as an independent country,” Blinken said. “Now, over the weekend they’ve had to defend Moscow, Russia’s capital, against mercenaries of Putin’s own making. . . . It was a direct challenge to Putin’s authority. . . . It shows real cracks.”

Blinken, unchallenged by his interviewer, Margaret Brennan, as he knew he would not be—why else would he appear on the show?—went on to suggest that the defection of the crazed Wagner leader would be a boon for Ukraine’s forces, whose slaughter by Russian troops was ongoing as he spoke. “To the extent that it presents a real distraction for Putin, and for Russian authorities, that they have to look at—sort of mind their rear as they’re trying to deal with the counter offensive in Ukraine, I think that creates even greater openings for the Ukrainians to do well on the ground.”

At this point was Blinken speaking for Joe Biden? Are we to understand that this is what the man in charge believes?

We now know that the chronically unstable Prigozhin’s revolt fizzled out within a day, as he fled to Belarus, with a no-prosecution guarantee, and his mercenary army was mingled into the Russian army. There was no march on Moscow, nor was there a significant threat to Putin’s rule.

Pity the Washington columnists and national security correspondents who seem to rely heavily on official backgrounders with White House and State Department officials. Given the published results of such briefings, those officials seem unable to look at the reality of the past few weeks, or the total disaster that has befallen the Ukraine military’s counter-offensive.

So, below is a look at what is really going that was provided to me by a knowledgeable source in the American intelligence community:

“I thought I might clear some of the smoke. First and most importantly, Putin is now in a much stronger position. We realized as early as January of 2023 that a showdown between the generals, backed by Putin, and Prigo, backed by anti-Russian extremists, was inevitable. The age-old conflict between the ‘special’ war fighters and a large, slow, clumsy, unimaginative regular army. The army always wins because they own the peripheral assets that make victory, either offensive or defensive, possible. Most importantly, they control logistics. special forces see themselves as the premier offensive asset. When the overall strategy is offensive, big army tolerates their hubris and public chest thumping because SF are willing to take high risk and pay a high price. Successful offense requires a large expenditure of men and equipment. Successful defense, on the other hand, requires husbanding these assets.

“Wagner members were the spearhead of the original Russian Ukraine offensive. They were the ‘little green men’. When the offensive grew into an all-out attack by the regular army, Wagner continued to assist but reluctantly had to take a back seat in the period of instability and readjustment that followed. Prigo, no shy violet, took the initiative to grow his forces and stabilize his sector.

“The regular army welcomed the help. Prigo and Wagner, as is the wont of special forces, took the limelight and took the credit for stopping the hated Ukrainians. The press gobbled it up. Meanwhile, the big army and Putin slowly changed their strategy from offensive conquest of greater Ukraine to defense of what they already had. Prigo refused to accept the change and continued on the offensive against Bakhmut. Therein lies the rub. Rather than create a public crisis and court-martial the asshole [Prigozhin], Moscow simply withheld the resources and let Prigo use up his manpower and firepower reserves, dooming him to a stand-down. He is, after all, no matter how cunning financially, an ex-hot dog cart owner with no political or military accomplishments.

“What we never heard is three months ago Wagner was cycled out of the Bakhmut front and sent to an abandoned barracks north of Rostov-on-Don [in southern Russia] for demobilization. The heavy equipment was mostly redistributed, and the force was reduced to about 8,000, 2,000 of which left for Rostov escorted by local police.

“Putin fully backed the army who let Prigo make a fool of himself and now disappear into ignominy. All without raising a sweat militarily or causing Putin to face a political standoff with the fundamentalists, who were ardent Prigo admirers. Pretty shrewd.”

There is an enormous gap between the way the professionals in the American intelligence community assess the situation and what the White House and the supine Washington press project to the public by uncritically reproducing the statements of Blinken and his hawkish cohorts.

The current battlefield statistics that were shared with me suggest that the Biden administration’s overall foreign policy may be at risk in Ukraine. They also raise questions about the involvement of the NATO alliance, which has been providing the Ukrainian forces with training and weapons for the current lagging counter-offensive. I learned that in the first two weeks of the operation, the Ukraine military seized only 44 square miles of territory previously held by the Russian army, much of it open land. In contrast, Russia is now in control of 40,000 square miles of Ukrainian territory. I have been told that in the past ten days Ukrainian forces have not fought their way through the Russian defenses in any significant way. They have recovered only two more square miles of Russian-seized territory. At that pace, one informed official said, waggishly, it would take Zelensky’s military 117 years to rid the country. of Russian occupation.

The Washington press in recent days seems to be slowly coming to grips with the enormity of the disaster, but there is no public evidence that President Biden and his senior aides in the White House and State Department aides understand the situation.

Putin now has within his grasp total control, or close to it, of the four Ukrainian oblasts—Donetsk, Kherson, Lubansk, Zaporizhzhia—that he publicly annexed on September 30, 2022, seven months after he began the war. The next step, assuming there is no miracle on the battlefield, will be up to Putin. He could simply stop where he is, and see if the military reality will be accepted by the White House and whether a ceasefire will be sought, with formal end-of-war talks initiated. There will be a presidential election next April in Ukraine, and the Russian leader may stay put and wait for that—if it takes place. President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine has said there will be no elections while the country is under martial law.

Biden’s political problems, in terms of next year’s presidential election, are acute—and obvious. On June 20 the Washington Post published an article based on a Gallup poll under the headline “Biden Shouldn’t Be as Unpopular as Trump—but He Is.” The article accompanying the poll by Perry Bacon, Jr., said that Biden has “almost universal support within his own party, virtually none from the opposition party and terrible numbers among independents.” Biden, like previous Democratic presidents, Bacon wrote, struggles “to connect with younger and less engaged voters.” Bacon had nothing to say about Biden’s support for the Ukraine war because the poll apparently asked no questions about the administration’s foreign policy.

The looming disaster in Ukraine, and its political implications, should be a wake-up call for those Democratic members of Congress who support the president but disagree with his willingness to throw many billions of good money after bad in Ukraine in the hope of a miracle that will not arrive. Democratic support for the war is another example of the party’s growing disengagement from the working class. It’s their children who have been fighting the wars of the recent past and may be fighting in any future war. These voters have turned away in increasing numbers as the Democrats move closer to the intellectual and moneyed classes.

If there is any doubt about the continuing seismic shift in current politics, I recommend a good dose of Thomas Frank, the acclaimed author of the 2004 best-seller What’s the Matter with Kansas? How Conservatives Won the Heart of America, a book that explained why the voters of that state turned away from the Democratic party and voted against their economic interests. Frank did it again in 2016 in his book Listen, Liberal: Or, Whatever Happened to the Party of the People? In an afterword to the paperback edition he depicted how Hillary Clinton and the Democratic Party repeated—make that amplified—the mistakes made in Kansas en route to losing a sure-thing election to Donald Trump.

It may be prudent for Joe Biden to talk straight about the war, and its various problems for America—and to explain why the estimated more than $150 billion that his administration has put up thus far turned out to be a very bad investment.