Orson Welles Narrates Animations of Plato’s Cave and Kafka’s “Before the Law,” Two Parables of the Human Condition

By Colin Marshall

Source: Open Culture

You’re held captive in an enclosed space, only able faintly to perceive the outside world. Or you’re kept outside, unable to cross the threshold of a space you feel a desperate need to enter. If both of these scenarios sound like dreams, they must do so because they tap into the anxieties and suspicions in the depths of our shared subconscious. As such, they’ve also proven reliable material for storytellers since at least the fourth century B.C., when Plato came up with his allegory of the cave. You know that story nearly as surely as you know the ancient Greek philosopher’s name: a group of human beings live, and have always lived, deep in a cave. Chained up to face a wall, they have only ever seen the images of shadow puppets thrown by firelight onto the wall before them.

To these isolated beings, “the truth would be literally nothing but the shadows of the images.” So Orson Welles tells it in this 1973 short film by animator Dick Oden. In his timelessly resonant voice that complements the production’s hauntingly retro aesthetic, Wells then speaks of what would happen if a cave-dweller were to be unshackled.

“He would be much too dazzled to see distinctly those things whose shadows he had seen before,” but as he approaches reality, “he has a clearer vision.” Still, “will he not be perplexed? Will he not think that the shadows which he formerly saw are truer than the objects which are now shown to him?” And if brought out of the cave to experience reality in full, would he not pity his old cavemates? “Would he not say, with Homer, better to be the poor servant of a poor master and to endure anything rather than think as they do and live after their manner?”

Plato’s cave wasn’t the first parable of the human condition Welles narrated. Just over a decade earlier, he engaged pinscreen animator Alexandre Alexeieff (he of Night on Bald Mountain and and “The Nose,” previously featured here on Open Culture) to illustrate his reading of Franz Kafka’s story “Before the Law.” The law, in Kafka’s telling, is a building, and before that building stands a guard. “A man comes from the country, begging admittance to the law,” says Welles. “But the guard cannot admit him. May he hope to enter at a later time? That is possible, said the guard.” Yet somehow that time never comes, and he spends the rest of his life awaiting admission to the law. “Nobody else but you could ever have obtained admittance,” the guard admits to the man, not long before the man expires of old age. “This door was intended only for you! And now, I’m going to close it.”

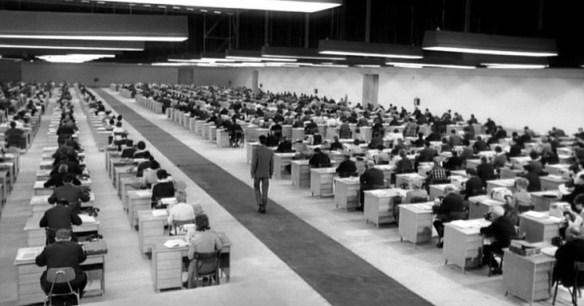

“Before the Law” describes a grimly absurd situation, as does Welles’ The Trial, the film to which it serves as an introduction. Adapted from another work of Kafka’s, specifically his best-known novel, it also concerns itself with the legal side of human affairs, at least on the surface. But when it becomes clear that the crime with which its bureaucrat protagonist Josef K. has been charged will never be specified, the story plunges into an altogether more troubling realm. We’ve all, at one time or another, felt to some degree like Joseph K., persecuted by an ultimately incomprehensible system, legal, social, or otherwise. And can we help but feel, especially in our highly mediated 21st century, like Plato’s immobilized human, raised in darkness and made to build a worldview on illusions? As for how to escape the cave — or indeed to enter the law — it falls to each of us individually to figure out.