By Charles Hugh Smith

Source: Of Two Minds

Economists and pundits are falling all over themselves to declare the US is chugging along splendidly, and to express their frustration with the public for their curmudgeonly lack of enthusiasm. For example: If this is a bad economy, please tell me what a good economy would look likeWe should acknowledge that things are going well, even as we continue to look for problems to solve and How the Recession Doomers Got the U.S. Economy So Wrong.

My intention is not to slam Noah Smith or Derek Thompson. I follow their work and gain value from their analysis.

The point I want to make is we only manage what we measure, and the reliance on statistics that are overly broad and easily distorted/gamed leads to generalizations that ignore consequential cause and effect: we are fooled by overly broad and easily distorted/gamed statistics and enlightened by looking at what is not measured or measured inadequately.

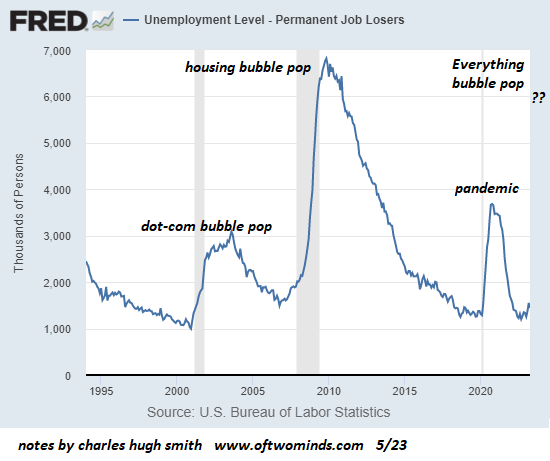

The consensus holds that inflation is declining rapidly and unemployment remains low, so the economy is doing great. Please glance at Chart #1 below to see what enthuses the mainstream: the unemployment rate is near historic lows.

But this measure leaves out a great deal of consequential factors. It’s well-known that the unemployment rate is distorted / gamed by leaving out everyone who is in the workforce but not “actively seeking work.” So what does this official unemployment rate actually measure? Not the percentage of the workforce that has a job.

Nor does it measure underemployment–those working far below their potential–or job insecurity or the percentage of workers being pushed into burnout–all consequential reflections of the real economy. All of these are potentially causal factors in why US productivity has fallen so dramatically.

And speaking of productivity, that’s the ultimate source of prosperity–not speculative bubbles or debt-binging. If productivity is tanking, eventually there are negative economic consequences that will be distributed to some segments of the populace, very likely asymmetrically.

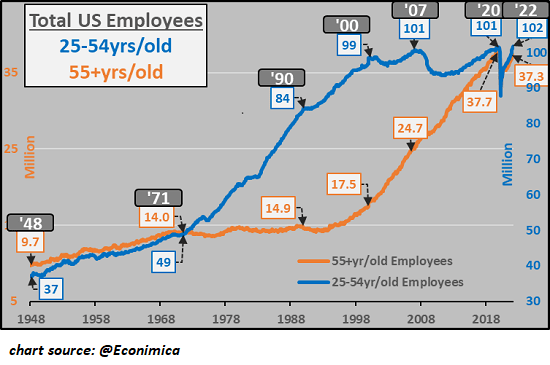

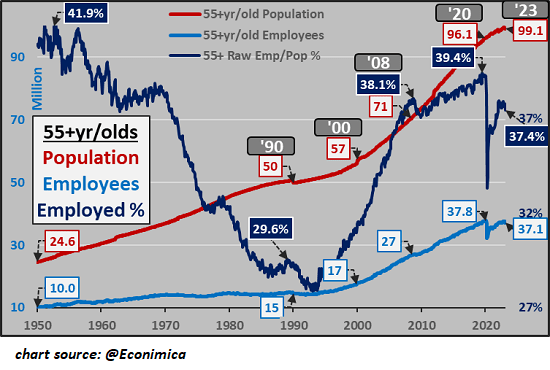

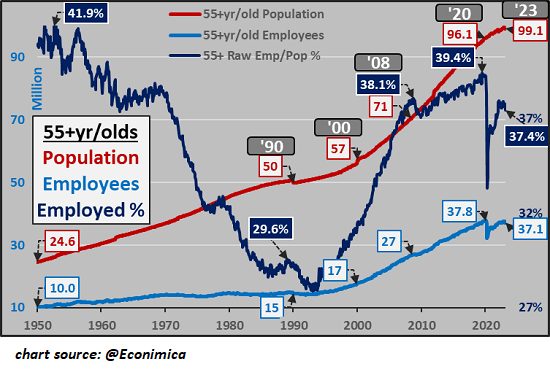

Such a broad-brush measure also ignores the consequences of demographics. Please glance at chart #2 below, of the 55 and over population and workforce. Note that virtually all the 20+ million jobs the US economy added in the past two decades are in this older workforce, which is of course steaming steadily into retirement, even as the percentage of this cohort who continues working has soared.

In other words, virtually all the job growth is the result of older workers working longer. Yes, 70 is the new 50, but try doing the same work at 70 that you did when you were 50. Sure, some people forego retirement because they love their work so much, but we don’t measure how many are still working because they have to for pressing financial reasons.

Have you observed the age of service workers and skilled workers recently? Do you reckon they really love working at Burger King so much that they’re doing it for enjoyment?

What if we measured financial pressures and job insecurity rather than risibly bogus “unemployment”? Would the economy still look so wonderful and resilient?

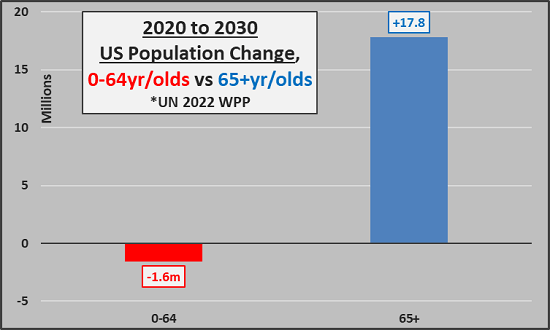

Chart #3 shows that virtually all the population growth ahead is in the cohort of older workers 65+ years old heading into retirement. So the workforce is rapidly aging and the unspoken / unexamined assumption is tens of millions of new workers will enter the workforce with the same skills, motivation, dedication and values as the tens of millions retiring.

But the demographics simply don’t support this breezy assumption.

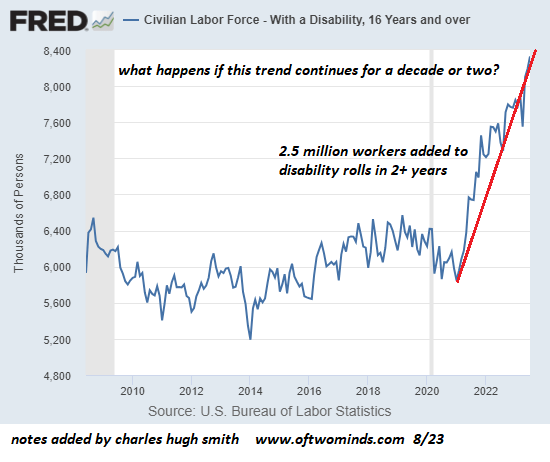

Now glance at chart #4 which depicts the extraordinary rise in the number of workers who are now disabled. The causes of this are being debated (the pandemic obviously plays a role), but 2.5 million workers leaving the workforce in a few years is something that could be consequential if the trend continues. An assumption that this is a one-off is baseless until proven otherwise.

Once again, demographics, productivity and factors such as disability and burnout are not part of the unemployment, GDP and inflation measures currently being touted as proof of economic nirvana.

Item #1 of what’s not even measured is the crapification of goods and services. I addressed this in The “Crapification” of the U.S. Economy Is Now Complete (February 9, 2022) and Stainless Steal (February 26, 2023).

How do we measure the “inflation”–i.e. a loss of purchasing power–when appliances that lasted 20 years a generation ago now break down in 5 years? Where does that 75% decline in utility and durability show up in the official inflation data? How about the tools that once lasted a lifetime now breaking after a few years?

It’s been estimated that America’s food has lost 30% of its nutritive value in the past few decades. Protein per gram has dropped, trace nutrients have dropped, and so on. Rather than pursue sustainably nutrient-rich soil, Big Ag has maximized profits by dumping natural-gas-derived chemical fertilizers on depleted soil to boost production of nutrient-poor, tasteless “product.” A product deemed “organic” offers no guarantee that the soil isn’t depleted of nutrients.

Could this decline have anything to do with the American populace’s increasingly poor health? Nobody knows because these massive declines in quality and value aren’t measured and are certainly not part of the risibly bogus measures of unemployment, GDP and inflation.

The official inflation rate ignores the multi-decade decline in the purchasing power of wages. Rents have soared 25% in a few years, and economists are looking at 5% increases in wages and worrying about the potential inflationary impact of workers’ wages not keeping up with real-world inflation.

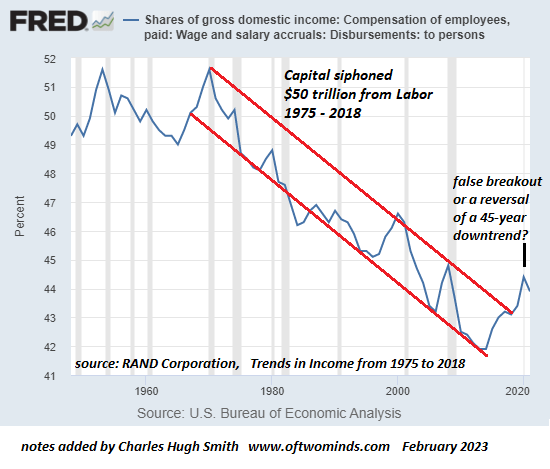

Cheerleading economists and pundits never mention the $50 trillion siphoned from labor by capital over the past 45 years. They also don’t mention the rising trend of loading more work on employees rather than hire more employees, or as a response to not being able to find qualified new hires.

Funny how rosy the picture can be tinted when all the consequential forces are ignored. But this studied ignorance characterizes the American elite, who delight in whining about airfares and travel delays, and finding someone to fix their pool pump. I address our Terminally Stratified Society here:

The Wealthy Are Not Like You and Me–Our Terminally Stratified Society (August 3, 2023)

This protected elite don’t have to put up with the crapified goods and services which generate their capital gains and income. Their wealth and income enable their detachment from the crapified economy the bottom 90% experience. Their experience of the bottom 90% is as service workers, delivery people, etc. who serve their entitled tastes.

Correspondent Tomasz G. provided a telling excerpt from Houellebecq’s The Possibility of an Island:

“… the rich certainly like the company of the rich, no doubt it calms them, it’s nice for them to meet beings subject to the same torments as they are, and who seem to form a relationship with them that is not totally about money; it’s nice for them to convince themselves that the human species is not uniquely made up of predators and parasites… “

As correspondent Ryan R. observed, America’s privileged elites“were born on third, stole home (via asset inflation) and still think they hit that home run.”

We know who the parasites are, but economists and pundits are safely blind to America’s neofeudal aristocracy. After all, who butters the bread of economists and pundits?

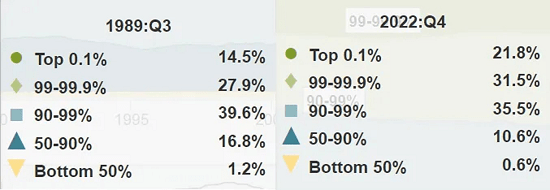

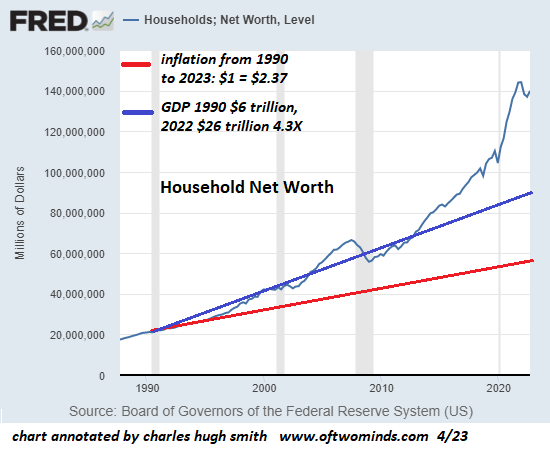

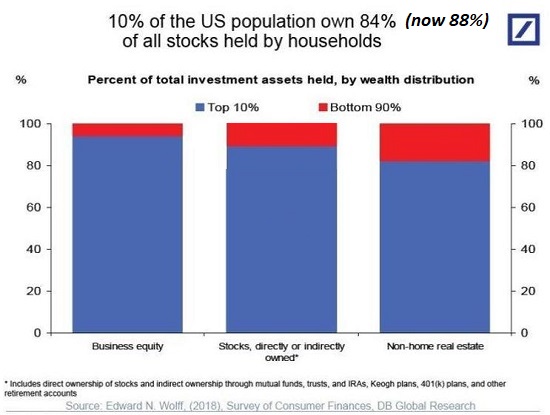

Is it unsurprising there are no measures of neofeudalism or elite privilege? As for the incredible concentration of wealth in the top tiers and the resulting decline in the bottom 90%’s share of the nation’s wealth–nothing to see here, just globalization and financialization doing their thing. What matters is booking my next flight to yet another conference of economists and pundits where we nod our heads and dare not admit all the conferences are nothing but echo chambers of the privileged elites.

Cheerleading economists and pundits completely ignore the consequences of the system being rigged to favor capital and the already-wealthy who were given the means to buy assets back when they were cheap and affordable to the middle-class. Now that the system generates speculative credit-asset bubbles to create “the wealth effect,” assets such as homes in desirable regions are out of reach of the bottom 90%.

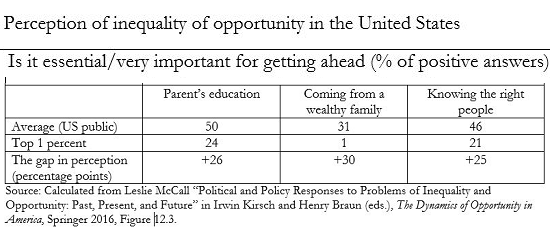

Please study the six charts below of wealth inequality. Try not to laugh out loud when you see that the top 1% reckon that “coming from a wealthy family” has near-zero impact on “getting ahead in America.”

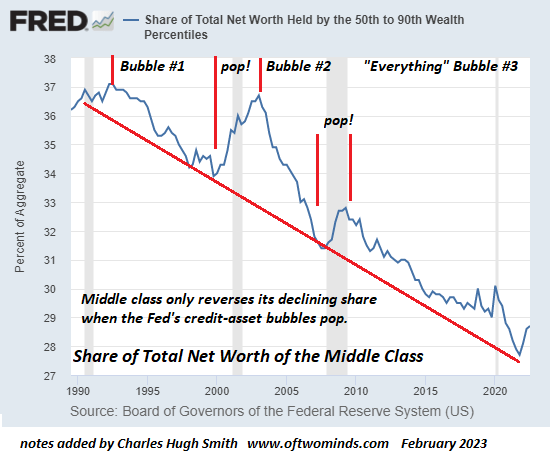

Also note the steady decline in the middle class percentage of national wealth, and how the middle class’s share only rises when the credit-asset bubbles that have enriched the top 10% deflate, a bubble-pop that never lasts longer than a few months thanks to the policies that favor the already-rich at the expense of those who don’t own stocks, rental properties, municipal bonds, etc.

Economists and pundits steer well clear of the eventual social and political consequences of America’s entrenched neofeudal wealth-income inequality. That this neofeudal configuration is inherently destabilizing–never mind, we don’t measure that, look at the wunnerful unemployment and inflation charts!

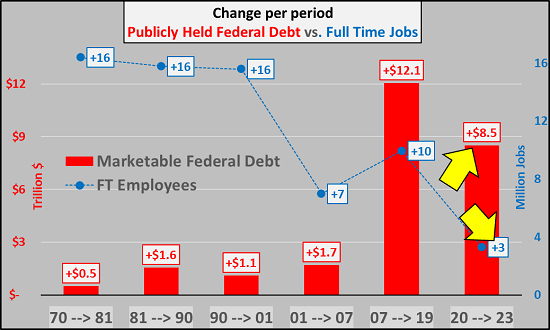

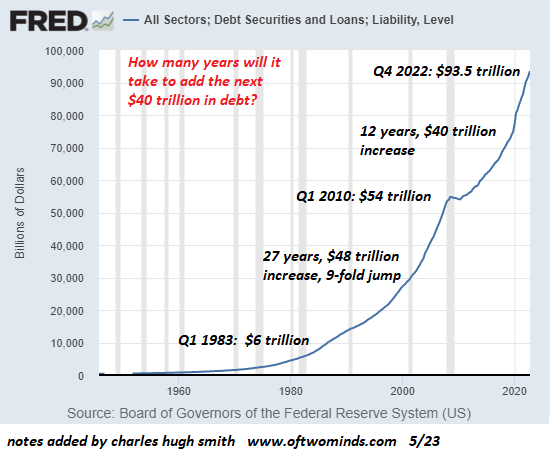

Lastly, consider the skyrocketing federal debt in terms of how many jobs are created in the era of soaring federal spending and debt. (Charts courtesy of CH / Economica) Debt doesn’t matter to economists and pundits, and neither does its diminishing effect on GDP and employment. The same can be said of total debt (public and private), which is skyrocketing (last chart): diminishing returns writ large as higher interest rates are embedded in the policy excesses and neofeudal structure of the past 45 years.

In essence, nothing that is consequential is properly quantified, so the pundit class keeps insisting everything is wunnerful and is mystified why people are so foolishly dissatisfied with our wunnerful economy. The reason why people are not buying the fantasyland story is they have to live and work in the crapified real economy, as serfs serving the economist-punditry-elite aristocracy.

If we want to avoid being led astray by misleading measures, we must seek enlightenment in what isn’t being measured or is cast aside as inconvenient to the “economy is wunnerful” party line.