By Kim Nicolini

Source: CounterPunch

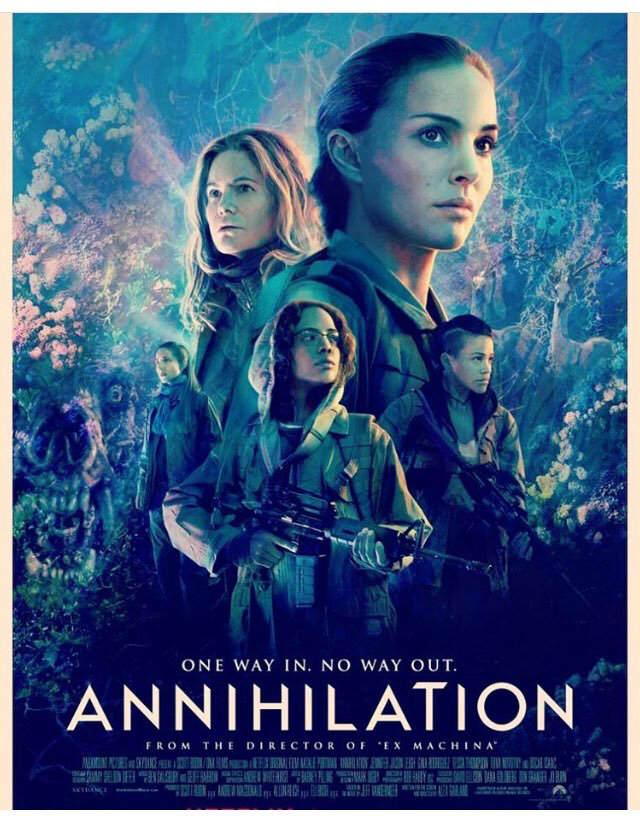

If you go see Alex Garland’s Annihilation (2018) – and I highly recommend you see this film in an actual movie theater with a big screen and big sound –, you are in for a trip. Not a road trip. Not a good trip. But a bad trip. You may ask why I am urging you to see a film that will pull the ground out from under you, defy delivering a tidy narrative, refuse to answer your questions, and leave you in a state of discombobulated horror as if you just experienced a 115 minute very bad trip. There are a lot of reasons to join Garland’s journey into a shaky world where reproduction leads to destruction and where the further you go into the film the further you will find yourself separated from any known reality (just as the further the main characters delve into the ominous and alien Shimmer, the further they come unglued). At one point in the film, female scientist Dr. Ventress (Jennifer Jason Leigh) questions whether all the women who reside at the film’s center have lost their minds. After watching the film, you may very well ask yourself the same thing. But that is the power of the film. By provoking the audience to lose their minds, toss all rational thought to the wind, and deconstruct the most primal notions of stability, this sci-fi horror film unveils the fears that seep through collective humanity like a terminal illness and show the unnatural and terrifying impact of human intervention with the natural world.

The movie is built on the basic sci-fi premise of a team of scientists sent on an expedition to explore an alien anomaly – in this case, the Shimmer. This mysterious form sprouted from an occurrence at a lighthouse and is rapidly devouring a national park and its surroundings, and it is hell bent on eating up all humankind and the earth it occupies (emphasis on the term occupation). Annihilation is astoundingly beautiful while also being exceptionally terrifying. It will take you into an alluring yet unnerving world that reflects our own world through myriad lenses. The Shimmer takes the very substance of all life – DNA – and refracts it into a kaleidoscopic array of mutant variations. Most of them are terrifying, even when they are beautiful, and the realm of this film is one of absolute instability.

Like the characters in the film, we presently occupy an environment of fear, where every day we are confronted with new terrors and new monsters bombarding the airwaves and the internet, a world which is being ripped from the core, where they natural landscape is threatened to be mutated by monster drills, where borders are pushed at us as if they are threats, and where females are both the source of growing power and the source of tremendous social anxiety. These and so many other things are delivered in Garland’s surreal portrait of four women on a scientific expedition into the unknown realm of the Shimmer which is rapidly consuming the southern gulf coast and mutating or killing everyone who enters it.

The film is based on Jeff VanderMeer’s 2014 novel, and your first question may be how well Garland has adapted the book for screen. Well, the book is the first thing he annihilates, so don’t attempt to compare. The material of the book inspired the film, but Garland acts not unlike the Shimmer. He has refracted the DNA of the book into its own species, something that none of us has ever seen before. In the film, the central Scientist Lena (Natalie Portman) discovers that all mutated plant species within the Shimmer are connected to one shared root system. VanderMeer’s book is like the movie’s root system from which Garland has conceived his own lusciously nightmarish film species, growing a whole forest of ideas and visions that multiply in glorious weirdness.

Garland outwardly states that he engages in an anarchistic approach to filmmaking. He resists leadership and debunks the idea of the auteur and refuses to be one (though both films he directed – Ex Machina (2014) and Annihilation bear striking similarities in aesthetics, production, and themes). An Alex Garland film is firmly and concretely an Alex Garland film. There is no way to mistake Garland’s use of glass and reflections (sliding doors as eerie otherworldly portals/prisons) or his cinematic obsession with reproduction (girl-bots and genetic engineering) for the films of anyone else. I commend Garland for his cooperative approach to filmmaking and for stepping back and letting people do what they are good at, trusting the experts he employs to do their job and refusing to interfere with their work. For example, when he partnered with Director of Photography Rob Hardy (also DP in Ex Machina), Garland didn’t dictate what lens or camera to use. He respects his DP as a collaborative artist within a team of collaborative artists, and he trusts that together they will produce uniquely beautiful and unsettling films. Likewise, Garland gives free reign to his actors to improvise, reinvent characters, and add their own unique dimensionality. His anarchistic approach to filmmaking shines through every surface of his films, and the surfaces in Annihilation indeed are magically shiny, slick with water, glistening with reflections, and refracted through glowing prisms.

Perhaps, Garland’s filmmaking anarchy also leads the audience to the sense that we are entering a world that never existed before because it only exists as a result of a distinct collaborative artistic process. It is a movie that can only result from a very specific mutation of elements. Just as the film relies on the image of cellular reproduction to create unique species that did not preexist, the cellular interaction of human creative DNA in Garland’s films creates a new species of movie, and for many, that is unsettling.

People are comfortable with what is familiar, and Annihilation is not like anything we have seen before, though we may recognize elements of its underlying DNA. The initial reference to the lighthouse as the locus for obliterating norms and a destination for the film’s team of women to reach echoes Virginia Woolfe’s desperate plea for female autonomy, creative freedom, and liberation in her 1927 novel To the Lighthouse. The four female protagonists are headed to the source of the reproductive anomaly (representing a breach in the traditional female role as birther and caregiver), and they are mirroring an early work of feminist fiction through the lens of sci-fi horror (because reproduction and all its ramifications both intrigue and terrifify men who want to understand and control something they can’t entirely understand and control). To reach the lighthouse, the women have to trek through Area X, a former national park which has now become a mutated kill zone that bears an eerie resemblance to the infamous Zone in Andrei Tarkovsky’s cinematic masterpiece Stalker (Сталкер, 1979). As in the Zone, Area X jumbles time, seems to be plagued with the aftermath of an environmental catastrophe, seeps water from every surface, glows with a haze of timeless loss, and destabilizes all sense of location (compasses fail), communication (technology signals drop), and unravels logic and reason. It also evokes the sense of some kind of radioactive disaster. To follow through on the film’s exploration of cancer as an act of self-destruction, radiation can cure (cancer) or kill (bombs). Finally, staying rooted in 1979, the film’s hazy dream/nighmarescape recalls the directorial style of Ridley Scott, and the Shimmer’s central root system – a seething undulating network of organs that combined look like a horrifically alien birth canal – harken back to H.R. Geiger renditions of a monster-breeding alien reproduction system in Scott’s Alien (1979). In other words, though Annihilation is its own cinematic species, it possesses the DNA of its cinematic and literary ancestors, which gives the audience a thread of familiarity even as we are being thrown into a psychedelic whirlwind of confusion and terror.

Both Annihilation and Ex Machina have very solid aesthetic and thematic grounding – the conjoining of the organic and the artificial which creates another dimension of being. Both films obsessively dissect, interrogate, and reconstruct ideas of reproduction and the murky, often shifting, line between reproduction and self-destruction.

Ex Machina explores the traditional horror film approach to reproduction by showing what happens when men try to take on the female role of reproducing through technological and/or scientific intervention. In this film, not only is the man the one reproducing, but he reproduces women as objects of male consumption – porno objects who can cook dinner, suck your dick, and kick up some dust on the dance floor. But in the end, man can’t outdo woman as the great reproducer. The girl-bots win, playing on man’s weak spots – all-consuming lust and ego – the man cancer that causes him to eat himself in an act of selfish self-desctruction. The robo-girls beat both their inventor, who thinks his brains can buy him a pussy (on all fronts), and the nerdy tech geek who likes to believe he’s above fetishizing women when actually his attraction to a girl is ruled more by his hard-on than intellectual intrigue. The only one either of these men is kidding is themselves. And they lose, and . . . they kind of get off on it, which flips us back into that loop that never seems to close.

Annihilation, on the other hand, puts women front and center. Female bodies invade a male genre – a troop of scientists and/or military guys sent on a mission to learn the secrets of and destroy a mysterious alien force – the Shimmer. We are not accustomed to seeing women in these roles, so the film annihilates traditional male-dominated sci-fi horror narratives. With another nod to Alien and a tribute to Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley, these women righteously bear automatic weapons to fend off the alien forces that threaten them. Remember how adept Ripley was at wielding a blow torch? In one scene Portman’s Lena obliterates a gigantic mutated crocodile without batting an eye. She literally never blinks! Unlike its predecessor Ex Machina which is fixated on male-reproduction of female bodies, Annihilation focuses on a group of women who have somehow failed to reproduce. The central character Lena has destroyed her marriage and therefore snuffed her possible future as a mother. Anya (Gina Rodriguez) has infiltrated her body with drugs and booze instead of babies. Radek (Tessa Thompson) has actually “felt” life through self-destruction (cutting herself to the extent that her arms are mapped with scars) rather than giving life through reproduction. Finally, Ventress has no connections to anyone, projects as if she is an ether trace of a rapidly vanishing body. Ventress is, it turns out, dying of cancer – the film’s stand-in metaphor for toxic reproduction, since cancer is the reproduction of cells to the point of biological annihilation.

The film opens with a close-up of cells multiplying under a microscope. We learn very quickly that they are cancerous cells from a female cervix – the gateway (or gatekeeper) to reproduction. From the film’s onset, reproduction is under attack (being annihilated). As we enter deeper into the Shimmer with the four women, we learn that cellular reproduction can be both beautiful and toxic. As Dr. Ventress states: “It is the source of all life, and of all death.” Therein lies the great conundrum, and the underlying horror of the movie (because this is a Sci-Fi horror film). By vividly exploring multiple angles of Reproduction Gone Wrong – from the Shimmer’s mutated plants and creatures to lethal cancer –, Annihilation taps into some of the most prevalent collective social fears. Over-population (one of the greatest threats to the planet) is shown as both beautiful (“Look at all those gorgeous and strange flowers!”) and as claustrophobic and strangulating (“Look how that mutated corpse is sprouting from a tapestry of flowers!”). Fear of scientific intervention in human creation and the potential horrors of genetic engineering confront us full-body through abominable mutated creatures, some of which literally open their mouths and swallow us. A rampaging bear howls with the voice of a dead woman. A female scientist sprouts stems and leaves and morphs into a cross-species plant.

At its core, the film confronts one of the biggest social fears that has been planted so deeply in the collective unconscious that many people are unaware of it. Even at this point in the 21st century when you would think people would “know better,” the large majority of the population – both male and female – rely on the traditional role of women as mother caregivers for a sense of stability. This film destabilizes patriarchal order by refusing to put its lead female characters in maternal roles and instead putting them in the traditional male shoes of scientists, and in Lena’s case – Scientist Soldier.

Unlike the women’s bodies, the land in the Shimmer has no problem reproducing. It reproduces itself crazy. It reproduces itself to annihilation, one of the great conundrums of the film – that reproduction (as in cancer) leads to complete destruction. Still, the women push through the Shimmer as it refracts all DNA, reproducing mutant and sometimes terrifying life forms. Climbing through overgrown plants, encountering hybrid animals, and camping out in abandoned houses and military encampments, the women make their way through an iridescent beautifully toxic world. Shimmering wet rainbows resemble the iridescence of a biologically disastrous oil spill. Though terrified and with the very ground of their minds unraveling, the women keep pushing, even as their numbers dwindle, and they confront such images as a live autopsy and its resulting mutation; a psychotic rampaging monster bear; tree-humans/human-trees; alligator-shark hybrids; and myriad other grotesque surprises.

In the end, however, the most terrifying image is the one of reproduction and destruction when Lena confronts herself and births her mutated, alien replicant via a seething, pulsing psychedelic vagina. At once curiously alluring and beautifully horrific, the magnum opus of the film occurs in a scene that defies description but must be experienced on the big screen as the vagina swirls in fleshy prismatic colors, its form both bulging and opening. In the climatic act of self-reproduction and destruction, the screen/vagina opens into a bottomless black birth canal and swallows the audience. There are fewer things more terrifying than a psychedelic vagina the size of a theater screen opening its black hole to swallow you alive while giving birth to your mutated duplicate self.

One of the many reasons this film is so unsettling and delivers such an overwhelming sense of dread is that it refuses to offer any middle ground. Everything is turned on its head. Actions and environments are extreme. Women bear arms instead of children. Interior landscapes are eerily sterile, filled with plastic zippered rooms, stainless steel furniture, and windows reflecting windows reflecting more windows. Not one organic thing lives in the lab, except the women (and one dying man and a few men in hazmat suits). Outside, the landscape is abominably fertile. Creatures are like beautifully terrifying genetic experiments. The land is so pregnant, you could practically barf looking at it. It is both bulging with life and seething with decay. Seemingly lovely flowers evoke feminist fiber art run amok. Humans and nature blend not into a vision of utopian bliss, but into an unnerving psychedelic bad trip. While reproduction is supposed to be the act of life, in this world it is a death sentence where living things reproduce themselves to annihilation, echoing the metaphor of cancer – a disease in which the body actually consumes itself with its own cellular reproduction. The film itself is an act of reproduction, reproducing itself in movie theaters while audiences succumb to, absorb, and are mutated by its toxic beauty. This is the kind of movie you don’t easily forget. It will infiltrate your dreams. Next time you take a hike through a densely wooded forest, you may think twice before exploring that abandoned cabin.

The mismatch between humans and nature and its potential for disastrous consequences leads to some excellent moments of sci-fi horror (you will be terrified) while also questioning the nightmarish impact and consequences of human exploitation of the environment/natural world. Let’s close those national parks and drill! But remember, if you keep on drilling, you may give birth to a monster. Throughout the film, music is critical to the movie’s unsettling hallucinatory delivery. With a soundtrack composed by Portishead’s Geoff Barrow and long-time composer Ben Salisbury, the music is as large and imposing of a character as the mutant bear. Alternating between soft acoustic guitar from another era, full orchestral strings, assaultive horns and bombastically creepy synths, the music doesn’t tell us how to feel, it immerses us in feeling. Complementing the film with orchestral moans and sonic decay, the music tips the scales of this movie toward outright Very Bad Trip. But it’s an entertaining trip!

Annihilation may be the most mind-boggling movie of the century. As it builds and breeds and breathes and opens its mouth and swallows us whole, the movie oozes questions and refuses answers. Told from the single POV of the unreliable narrator Lena, we don’t know what to believe and not believe, what is happening, what is a demented hallucination, what is past, present, or future. In one scene, Anya screams over and over: “Lena is a liar! Lena is a liar!” And maybe she is. We never know. Since the story is strictly told from Lena’s perspective, we don’t know if she is lying to us. When asked to recount what happened in the Shimmer, her most common reply is: “I don’t know.” She doesn’t know, and neither do we, just like in the world outside the Shimmer where we are bombarded with “fake news,” false alarms, and paranoid manufactured distractions to prevent us from getting to answers.

At this point, you may be asking, “But what about Oscar Isaak and his character Kane?” He exists in ghost form, in memory, propped up by life support, leaking blood from mutated organs, or as a reconstituted alien being. In other words, he has been stripped of solidity. The central conjoining entities in the film are Lena and Kane, but Lena destroyed their marriage in an act of self-destruction. Lena, who introduces the cancer cells in the beginning of the film, is a cancer herself, and oddly the lone survivor, perhaps because she is the mutant cell that consumes everything in an act of self-destruction that ironically keeps her alive. I know – what a lot of confusing hogwash.

But the world is confusing hogwash! We live in a time of questions not answers, a time of abstract fear that permeates everything and saturates our very souls with instability. The earth is dying; the System is lying; our hearts and land are crying; and there are no fucking answers.

Launching a cast of women in traditional male roles and playing on the trope of cancer as the ultimate method of lethal reproduction, Annihilation blows a hole through just about everything known and turns it in an unknown. It annihilates preconceptions about conception; rational thought; traditional gender roles; cinematic genre; social expectations; definitions of species; fundamental biology, earth science; the possibility of future; application of human thought to unanswerable questions; and the idea of self itself. And the annihilation is both beautiful and horrific. The movie screen seems to actually breathe with mutated life as it sucks us into its tantalizing bad trip. And I loved every minute of it. Personally, I’d rather be on a bad trip that explores socio-political fears and anxiety through a hallucinatory cinematic lens rather than succumb to the excessively toxic reproduction and biased distortion of an unreal reality.