All Are Equal, Except Those Who Aren’t

By Nomi Prins

Source: TomDispatch.com

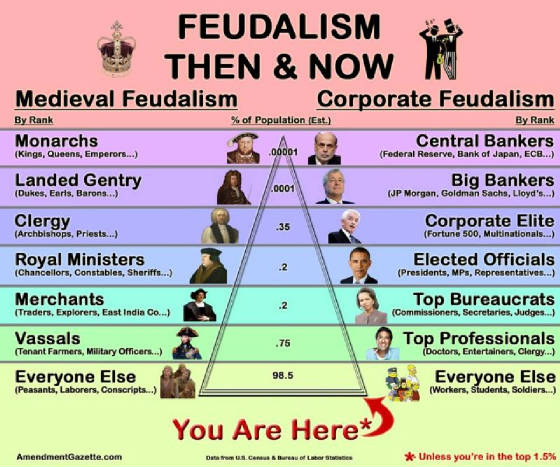

Like a gilded coating that makes the dullest things glitter, today’s thin veneer of political populism covers a grotesque underbelly of growing inequality that’s hiding in plain sight. And this phenomenon of ever more concentrated wealth and power has both Newtonian and Darwinian components to it.

In terms of Newton’s first law of motion: those in power will remain in power unless acted upon by an external force. Those who are wealthy will only gain in wealth as long as nothing deflects them from their present course. As for Darwin, in the world of financial evolution, those with wealth or power will do what’s in their best interest to protect that wealth, even if it’s in no one else’s interest at all.

In George Orwell’s iconic 1945 novel, Animal Farm, the pigs who gain control in a rebellion against a human farmer eventually impose a dictatorship on the other animals on the basis of a single commandment: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.” In terms of the American republic, the modern equivalent would be: “All citizens are equal, but the wealthy are so much more equal than anyone else (and plan to remain that way).”

Certainly, inequality is the economic great wall between those with power and those without it.

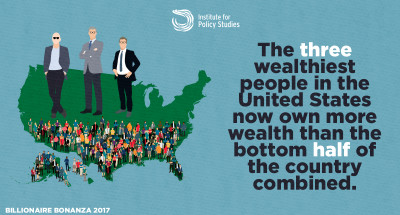

As the animals of Orwell’s farm grew ever less equal, so in the present moment in a country that still claims equal opportunity for its citizens, one in which three Americans now have as much wealth as the bottom half of society (160 million people), you could certainly say that we live in an increasingly Orwellian society. Or perhaps an increasingly Twainian one.

After all, Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner wrote a classic 1873 novel that put an unforgettable label on their moment and could do the same for ours. The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today depicted the greed and political corruption of post-Civil War America. Its title caught the spirit of what proved to be a long moment when the uber-rich came to dominate Washington and the rest of America. It was a period saturated with robber barons, professional grifters, and incomprehensibly wealthy banking magnates. (Anything sound familiar?) The main difference between that last century’s gilded moment and this one was that those robber barons built tangible things like railroads. Today’s equivalent crew of the mega-wealthy build remarkably intangible things like tech and electronic platforms, while a grifter of a president opts for the only new infrastructure in sight, a great wall to nowhere.

In Twain’s epoch, the U.S. was emerging from the Civil War. Opportunists were rising from the ashes of the nation’s battered soul. Land speculation, government lobbying, and shady deals soon converged to create an unequal society of the first order (at least until now). Soon after their novel came out, a series of recessions ravaged the country, followed by a 1907 financial panic in New York City caused by a speculator-led copper-market scam.

From the late 1890s on, the most powerful banker on the planet, J.P. Morgan, was called upon multiple times to bail out a country on the economic edge. In 1907, Treasury Secretary George Cortelyou provided him with $25 million in bailout money at the request of President Theodore Roosevelt to stabilize Wall Street and calm frantic citizens trying to withdraw their deposits from banks around the country. And this Morgan did — by helping his friends and their companies, while skimming money off the top himself. As for the most troubled banks holding the savings of ordinary people? Well, they folded. (Shades of the 2007-2008 meltdown and bailout anyone?)

The leading bankers who had received that bounty from the government went on to cause the Crash of 1929. Not surprisingly, much speculation and fraud preceded it. In those years, the novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald caught the era’s spirit of grotesque inequality in The Great Gatsby when one of his characters comments: “Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me.” The same could certainly be said of today when it comes to the gaping maw between the have-nots and have-a-lots.

Income vs. Wealth

To fully grasp the nature of inequality in our twenty-first-century gilded age, it’s important to understand the difference between wealth and income and what kinds of inequality stem from each. Simply put, income is how much money you make in terms of paid work or any return on investments or assets (or other things you own that have the potential to change in value). Wealth is simply the gross accumulation of those very assets and any return or appreciation on them. The more wealth you have, the easier it is to have a higher annual income.

Let’s break that down. If you earn $31,000 a year, the median salary for an individual in the United States today, your income would be that amount minus associated taxes (including federal, state, social security, and Medicare ones). On average, that means you would be left with about $26,000 before other expenses kicked in.

If your wealth is $1,000,000, however, and you put that into a savings account paying 2.25% interest, you could receive about $22,500 and, after taxes, be left with about $19,000, for doing nothing whatsoever.

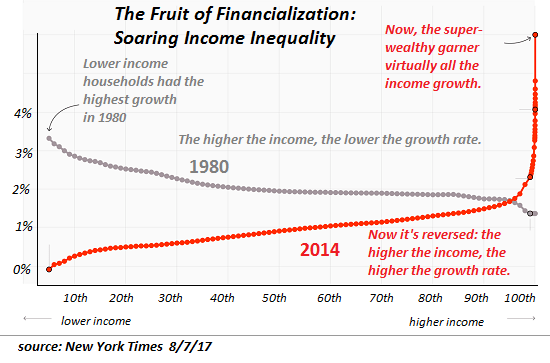

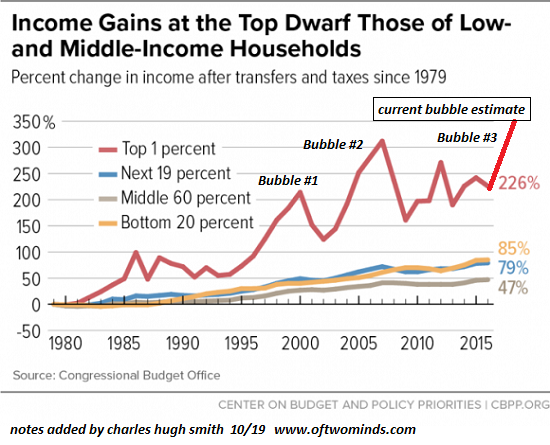

To put all this in perspective, the top 1% of Americans now take home, on average, more than 40 times the incomes of the bottom 90%. And if you head for the top 0.1%, those figures only radically worsen. That tiny crew takes home more than 198 times the income of the bottom 90% percent. They also possess as much wealth as the nation’s bottom 90%. “Wealth,” as Adam Smith so classically noted almost two-and-a-half-centuries ago in The Wealth of Nations, “is power,” an adage that seldom, sadly, seems outdated.

A Case Study: Wealth, Inequality, and the Federal Reserve

Obviously, if you inherit wealth in this country, you’re instantly ahead of the game. In America, a third to nearly a half of all wealth is inherited rather than self-made. According to a New York Times investigation, for instance, President Donald Trump, from birth, received an estimated $413 million (in today’s dollars, that is) from his dear old dad and another $140 million (in today’s dollars) in loans. Not a bad way for a “businessman” to begin building the empire (of bankruptcies) that became the platform for a presidential campaign that oozed into actually running the country. Trump did it, in other words, the old-fashioned way — through inheritance.

In his megalomaniacal zeal to declare a national emergency at the southern border, that gilded millionaire-turned-billionaire-turned-president provides but one of many examples of a long record of abusing power. Unfortunately, in this country, few people consider record inequality (which is still growing) as another kind of abuse of power, another kind of great wall, in this case keeping not Central Americans but most U.S. citizens out.

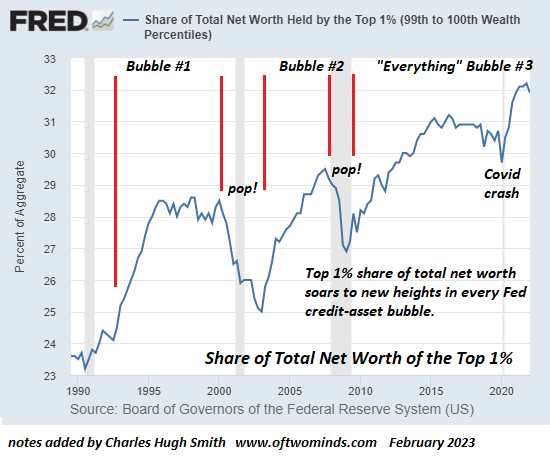

The Federal Reserve, the country’s central bank that dictates the cost of money and that sustained Wall Street in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007-2008 (and since), has finally pointed out that such extreme levels of inequality are bad news for the rest of the country. As Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said at a town hall in Washington in early February, “We want prosperity to be widely shared. We need policies to make that happen.” Sadly, the Fed has largely contributed to increasing the systemic inequality now engrained in the financial and, by extension, political system. In a recent research paper, the Fed did, at least, underscore the consequences of inequality to the economy, showing that “income inequality can generate low aggregate demand, deflation pressure, excessive credit growth, and financial instability.”

In the wake of the global economic meltdown, however, the Fed took it upon itself to reduce the cost of money for big banks by chopping interest rates to zero (before eventually raising them to 2.5%) and buying $4.5 trillion in Treasury and mortgage bonds to lower it further. All this so that banks could ostensibly lend money more easily to Main Street and stimulate the economy. As Senator Bernie Sanders noted though, “The Federal Reserve provided more than $16 trillion in total financial assistance to some of the largest financial institutions and corporations in the United States and throughout the world… a clear case of socialism for the rich and rugged, you’re-on-your-own individualism for everyone else.”

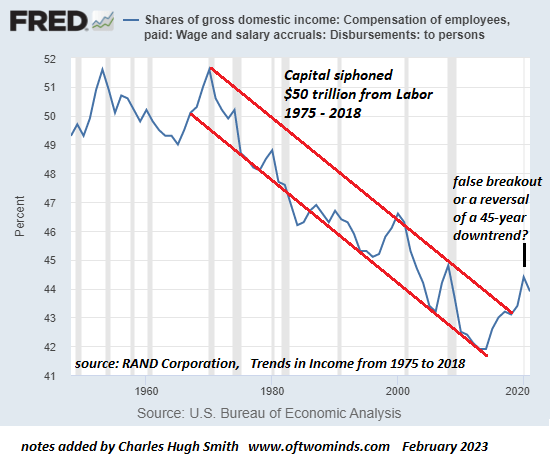

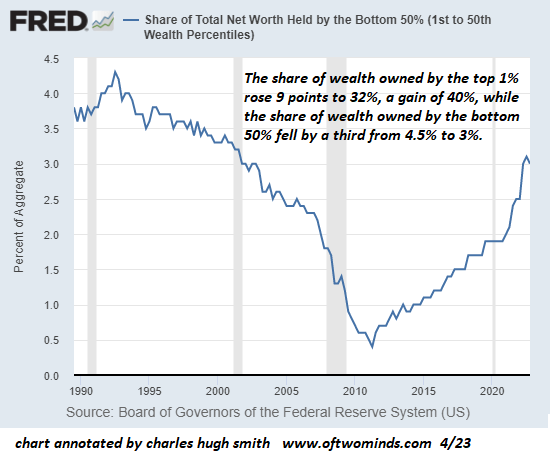

The economy has been treading water ever since (especially compared to the stock market). Annual gross domestic product growth has not surpassed 3%in any year since the financial crisis, even as the level of the stock market tripled, grotesquely increasing the country’s inequality gap. None of this should have been surprising, since much of the excess money went straight to big banks, rich investors, and speculators. They then used it to invest in the stock and bond markets, but not in things that would matter to all the Americans outside that great wall of wealth.

The question is: Why are inequality and a flawed economic system mutually reinforcing? As a starting point, those able to invest in a stock market buoyed by the Fed’s policies only increased their wealth exponentially. In contrast, those relying on the economy to sustain them via wages and other income got shafted. Most people aren’t, of course, invested in the stock market, or really in anything. They can’t afford to be. It’s important to remember that nearly 80% of the population lives paycheck to paycheck.

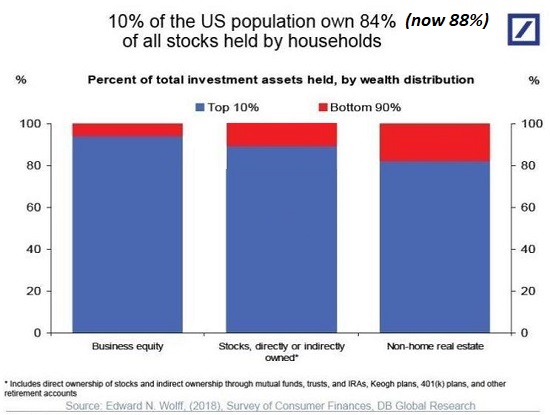

The net result: an acute post-financial-crisis increase in wealth inequality — on top of the income inequality that was global but especially true in the United States. The crew in the top 1% that doesn’t rely on salaries to increase their wealth prospered fabulously. They, after all, now own more than half of all national wealth invested in stocks and mutual funds, so a soaring stock market disproportionately helps them. It’s also why the Federal Reserve subsidy policies to Wall Street banks have only added to the extreme wealth of those extreme few.

The Ramifications of Inequality

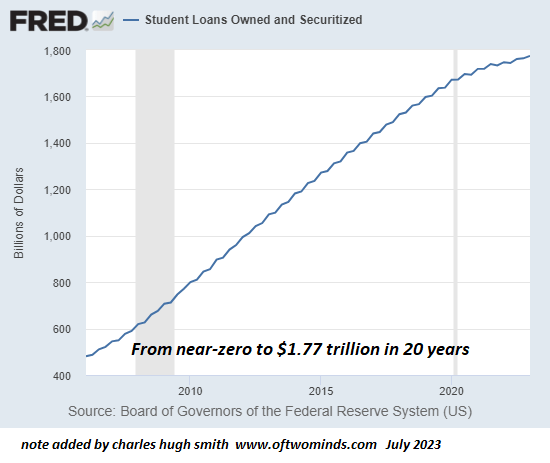

The list of negatives resulting from such inequality is long indeed. As a start, the only thing the majority of Americans possess a greater proportion of than that top 1% is a mountain of debt.

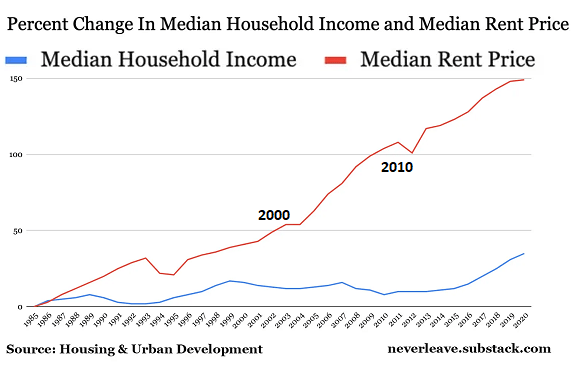

The bottom 90% are the lucky owners of about three-quarters of the country’s household debt. Mortgages, auto loans, student loans, and credit-card debt are cumulatively at a record-high $13.5 trillion.

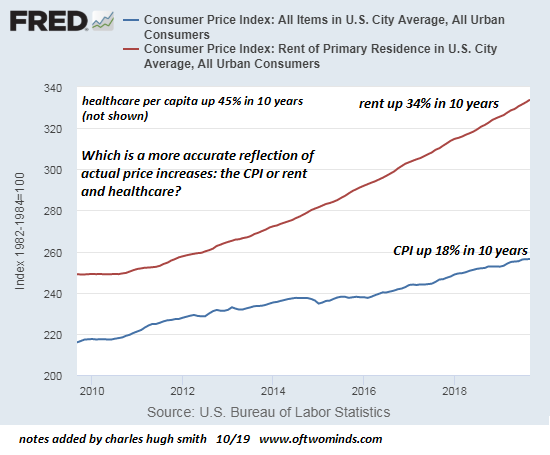

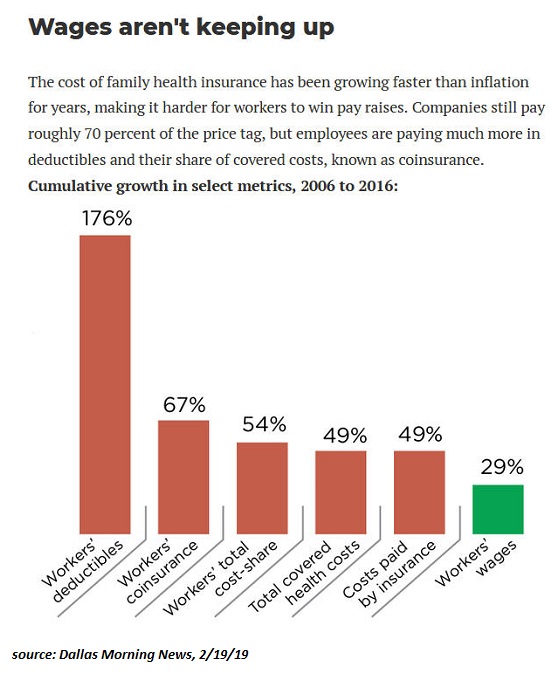

And that’s just to start down a slippery slope. As Inequality.org reports, wealth and income inequality impact “everything from life expectancy to infant mortality and obesity.” High economic inequality and poor health, for instance, go hand and hand, or put another way, inequality compromises the overall health of the country. According to academic findings, income inequality is, in the most literal sense, making Americans sick. As one study put it, “Diseased and impoverished economic infrastructures [help] lead to diseased or impoverished or unbalanced bodies or minds.”

Then there’s Social Security, established in 1935 as a federal supplement for those in need who have also paid into the system through a tax on their wages. Today, all workers contribute 6.2% of their annual earnings and employers pay the other 6.2% (up to a cap of $132,900) into the Social Security system. Those making far more than that, specifically millionaires and billionaires, don’t have to pay a dime more on a proportional basis. In practice, that means about 94% of American workers and their employers paid the full 12.4% of their annual earnings toward Social Security, while the other 6% paid an often significantly smaller fraction of their earnings.

According to his own claims about his 2016 income, for instance, President Trump “contributed a mere 0.002 percent of his income to Social Security in 2016.” That means it would take nearly 22,000 additional workers earning the median U.S. salary to make up for what he doesn’t have to pay. And the greater the income inequality in this country, the more money those who make less have to put into the Social Security system on a proportional basis. In recent years, a staggering $1.4 trillion could have gone into that system, if there were no arbitrary payroll cap favoring the wealthy.

Inequality: A Dilemma With Global Implications

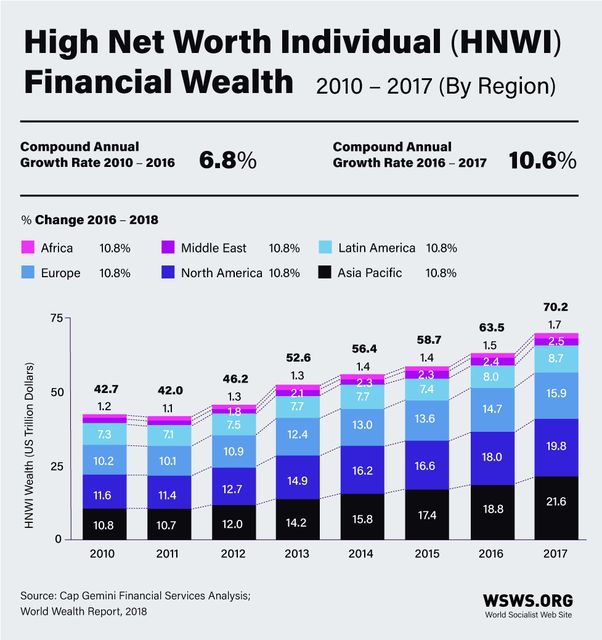

America is great at minting millionaires. It has the highest concentration of them, globally speaking, at 41%. (Another 24% of that millionaires’ club can be found in Europe.) And the top 1% of U.S. citizens earn 40 times the national average and own about 38.6% of the country’s total wealth. The highest figure in any other developed country is “only” 28%.

However, while the U.S. boasts of epic levels of inequality, it’s also a global trend. Consider this: the world’s richest 1% own 45% of total wealth on this planet. In contrast, 64% of the population (with an average of $10,000 in wealth to their name) holds less than 2%. And to widen the inequality picture a bit more, the world’s richest 10%, those having at least $100,000 in assets, own 84% of total global wealth.

The billionaires’ club is where it’s really at, though. According to Oxfam, the richest 42 billionaires have a combined wealth equal to that of the poorest 50% of humanity. Rest assured, however, that in this gilded century there’s inequality even among billionaires. After all, the 10 richest among them possess $745 billion in total global wealth. The next 10 down the list possess a mere $451.5 billion, and why even bother tallying the next 10 when you get the picture?

Oxfam also recently reported that “the number of billionaires has almost doubled, with a new billionaire created every two days between 2017 and 2018. They have now more wealth than ever before while almost half of humanity have barely escaped extreme poverty, living on less than $5.50 a day.”

How Does It End?

In sum, the rich are only getting richer and it’s happening at a historic rate. Worse yet, over the past decade, there was an extra perk for the truly wealthy. They could bulk up on assets that had been devalued due to the financial crisis, while so many of their peers on the other side of that great wall of wealth were economically decimated by the 2007-2008 meltdown and have yet to fully recover.

What we’ve seen ever since is how money just keeps flowing upward through banks and massive speculation, while the economic lives of those not at the top of the financial food chain have largely remained stagnant or worse. The result is, of course, sweeping inequality of a kind that, in much of the last century, might have seemed inconceivable.

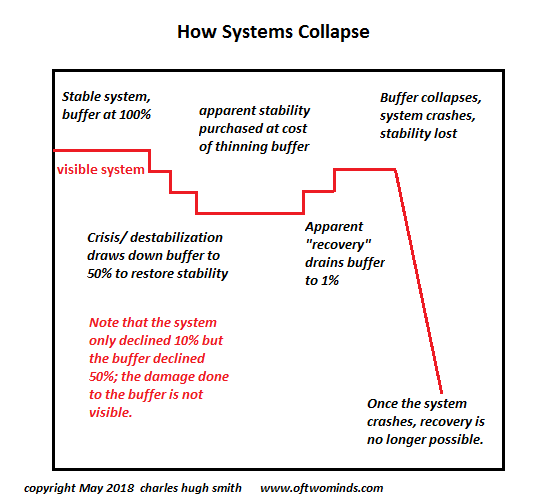

Eventually, we will all have to face the black cloud this throws over the entire economy. Real people in the real world, those not at the top, have experienced a decade of ever greater instability, while the inequality gap of this beyond-gilded age is sure to shape a truly messy world ahead. In other words, this can’t end well.

Nomi Prins, a former Wall Street executive, is a TomDispatch regular. Her latest book is Collusion: How Central Bankers Rigged the World (Nation Books). She is also the author of All the Presidents’ Bankers: The Hidden Alliances That Drive American Power and five other books. Special thanks go to researcher Craig Wilson for his superb work on this piece.