We’re winning: More progress has been made toward enlightened drug policies and treatment in the past five years than in the previous 25. Here’s an advocacy agenda to take us even closer to the future we need.

By Maia Szalavitz

Source: Substance.com

There has never been a more exciting time to be writing and thinking about drugs and addiction. For most of the ‘80s through the ‘00s, policy and treatment debates were stagnant, with all sides taking hardened positions and often repeating the same tired talking points. But now change is in the air and those who would like to see reform have a chance to make a real difference. By looking at where we’ve come from, we can see where we need to go.

Until 2011 or 2012, the war on drugs, while much bemoaned, was simply a fact of life, with pretty much everyone agreeing both about its failure and, simultaneously, about the impossibility of doing anything significantly different because of the “tough on crime” arms race between the Republicans and Democrats.

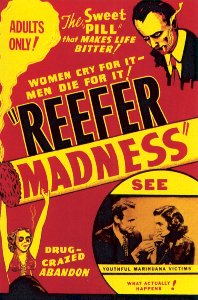

The science didn’t matter: No one seemed to care that marijuana was objectively less harmful than alcohol or tobacco or that our drug laws originated both in the time of Jim Crow and, quite explicitly, as a way of oppressing people of color by other means. In fact, merely stating these facts, as I did many times, would often get me in trouble with editors who wanted to “balance” them with a prohibitionist claim to prove that the publication was “objective”! No one ever seemed to consider balance when a drug warrior made a demonstrably untrue statement.

It didn’t matter that the data on needle exchange was overwhelmingly in favor—and that no study had ever found that it encouraged drug use or prolonged addiction. A quote by someone who was ideologically opposed had to be obtained, even though they had no data to back their concerns about these programs to prevent infection with HIV and hepatitis C “sending the wrong message.”

The failure of drug enforcement either to prevent or to reduce “drug epidemics” and the ineffectiveness of incarceration at fighting addiction was irrelevant, too, even as the necessity of such punitive efforts was simply accepted without question.

Nor did it matter that harsh, confrontational treatment was known both to backfire and to be incredibly common—Dr. Drew, Intervention, Beyond Scared Straight and similar shows even portrayed it as exemplary.

At the same time, 12-step supporters were adamant that their way was the only way—or at least the best way. Drug warriors were convinced that criminalization of both possession and sales was the only way to avoid addiction Armageddon—and even many people in recovery bought into the idea that law enforcement must always play a role in policies related to illegal drugs.

In 2000, for instance, during the fight over California’s Proposition 36, which gives drug users three chances at treatment before jail becomes a sentencing option, the Betty Ford Center was among the opponents. Speaking for a coalition that included the rehab, actor and sobriety advocate Martin Sheen wrote in an op-ed, “Without accountability and consequences, drug abusers have little incentive to change their behavior or take treatment seriously.” (He didn’t explain how Betty Ford gets alcoholics, whose drug is legal, to comply with care.) But Prop 36 passed anyway, an early sign of the drug war’s waning hold.

And so, even when reforms would actually send patients to rehabs, treatment providers remained firmly aligned with drug warriors on the necessity of harsh criminalization, while they begged for crumbs of financing from the abundant table of law enforcement and argued that treatment is better than jail.

Now, though, the winds have shifted. Four states and Washington, DC, have legalized recreational use of marijuana. President Obama has directed the justice department not to interfere with these experiments and said last week, “My suspicion is that you are going to see other states start looking at this.” California, which rejected recreational legalization as recently as 2010, may pass it in an expected 2016 ballot initiative. National polls show majority support for legalization.

Neither Colorado nor Washington—the first two states to legalize—has seen anything near the predicted disaster in the first year after the passage of the law. In fact, in Colorado, crime is down, auto fatalities are down and teen use is stable or declining. (Because Washington took longer to implement its regime, good statistics aren’t yet available).

All of this is excellent news for reformers. So what should be next on the agenda? Here are a few things I’d like to see, which I think could build on the increased openness to more effective policy:

1. Over-the-counter naloxone

Naloxone, an opioid antagonist that can reverse opioid overdose, is now widely available to first responders and, through many harm reduction agencies, to friends and families of people at risk. No adverse effects have been reported; just more and more lives saved. The FDA should make naloxone available over the counter, and sales should be subsidized or prices capped to make it affordable. This safe, effective lifesaver should be in every first-aid kit.

2. Expand access to medication-assisted treatment

As I noted recently, it’s outrageous that any doctor who discovers that a patient has an opioid problem can’t simply prescribe the most effective treatment: maintenance with Suboxone or methadone. Federal limits on the number of patients a doctor can have on maintenance and laws that literally ghettoize methadone treatment should be repealed. Insurance limits on prescribing also should be challenged: These exist for no other medical condition.

3. Decriminalize personal possession of all drugs

Now that even once-staunch prohibitionists like Kevin Sabet no longer argue strongly for arrest and incarceration of those who possess marijuana, why does it still make sense for heroin, cocaine or other illegal drugs?

82% of all drug arrests are for possession, and half of these are for marijuana. According to the ACLU, the US spends $3.1 billion annually arresting and adjudicating marijuana possession cases, and at least as much is likely to be spent on the other half of possession arrests for all other drugs. And yet no data suggests that arresting drug users for possession fights addiction or reduces crime: In fact, addicted people often get worse due to incarceration, with very little treatment available in jail.

Moreover, Portugal’s 10-plus-year experience of complete decriminalization has found it to be associated with less crime, more treatment and less disease. What’s not to like? The World Health Organization recently came out in favor of decriminalization. Drug reformers should not make marijuana arrests the only focus of their abolition campaign. Arrests for use are expensive, harmful and ineffective: They need to stop.

5. Reform treatment

People with addiction and their loved ones are often shocked at what occurs in treatment: Evidence-based care is so hard to find that even leading addiction researcher and former deputy drug czar Tom McLellan didn’t know where to turn when his son needed help in 2009. Anne Fletcher’s Inside Rehab, David Sheff’s Clean and this 2012 report from the Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse all demonstrate the need for better accountability from treatment providers.

To start, private and public insurers should simply refuse to pay for treatment that is little more than indoctrination into 12-step groups, which can be had for free at many church basements. Instead, treatment time should be devoted to evidence-based therapies like motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy, which aren’t free—and provider reimbursement should be based on results, respectful and empathetic care and genuine fidelity to evidence-based therapies.

And this isn’t a change that only opponents of 12-step programs should favor. Even those who are helped by the steps know that such treatment clearly violates the Eighth Tradition, which states that AA should be “forever nonprofessional” and that the 12th-step work of trying to bring others into the program should be unpaid. Both 12-step groups and treatment will ultimately be better off disentangled.

5. Reframe addiction

As I’ve argued here before, addiction is better characterized as a learning or developmental disorder than as a brain disease. While those who support the brain disease concept see it as a way of reducing stigma, in actual fact, this idea can increase fear and hatred of addicts because the notion of “brain damage” suggests permanence and poor odds for recovery.

What addiction actually does in the brain is similar to what love does—it strongly wires in new memories and pushes us to seek certain experiences. This is not “damage” or “destruction.” When we understand addiction as one more type of neurodiversity—not always a disability, sometimes even a source of strength—we’ll really cut stigma.

Also, it’s impossible to fight stigma while the legal system enforces it: The whole point of criminalizing drug possession is to stigmatize it. Without changing both criminalization and the view of addiction as the only disease treated by prayer and repentance, stigma reduction won’t get very far.

There’s much more, of course, but these are areas where real progress can be made. Never before have I seen more openness in this area: Now people who used to blanch at the words “harm reduction” are singing its praises and those who were once horrified by needle exchange are calling for naloxone. We still have a long way to go—and there’s always the chance of backlash—but as Martin Luther King, Jr., put it, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

Maia Szalavitz is the nation’s leading neuroscience and addiction journalist, and a columnist at Substance.com. She has contributed to Time, The New York Times, Scientific American Mind, the Washington Post and many other publications. She has also published five books, including Help at Any Cost: How the Troubled-Teen Industry Cons Parents and Hurts Kids (Riverhead, 2006), and is currently finishing her sixth, Unbroken Brain, which examines why seeing addiction as a developmental or learning disorder can help us better understand, prevent and treat it. Her previous column for Substance.com was about how to treat people who need, but misuse, opiate painkillers in a more helpful and enlightened way.