By Charles Hugh Smith

Source: Dangerous Minds

The difference between what we experience and what we’re told we experience creates a social schizophrenia that leads to self-destructive attitudes and behaviors.

What can popular television programs tell us about the zeitgeist (spirit of the age) of our culture and economy?

It’s an interesting question, as all mass media both responds to and shapes our interpretations and explanations of changing times. It’s also an important question, as mass media trends crystallize and express new ways of understanding our era.

Those who shape our interpretation of events also shape our responses. This of course is the goal of propaganda: Shape the interpretation, and the response predictably follows.

As a corporate enterprise, mass media’s goal is to make money—the more the better—and that requires finding entertainment products that attract and engage large audiences. The products that change popular culture are typically new enough to fulfill our innate attraction to novelty—but this isn’t enough. The product must express an interpretation of our time that was nascent but that had not yet found expression.

We can understand this complex process of crystallizing and giving expression to new contexts as one facet of the politics of experience.

The Politics of Experience

It is not coincidental that the phrase politics of experience was coined by a psychiatrist, R.D. Laing, for the phrase unpacks the way our internalized interpretation of experience can be shaped to create uniform beliefs about our society and economy that then lead to norms of behavior that support the political/economic status quo.

Here’s how Laing described the social ramifications in Chapter Four of his 1967 book, The Politics of Experience:

“All those people who seek to control the behavior of large numbers of other people work on the experiences of those other people. Once people can be induced to experience a situation in a similar way, they can be expected to behave in similar ways. Induce people all to want the same thing, hate the same things, feel the same threat, then their behavior is already captive – you have acquired your consumers or your cannon-fodder.”

For Laing, the politics of experience is not just about influencing social behavior – it has an individual, inner consequence as well:

“Our behavior is a function of our experience. We act according to the way we see things. If our experience is destroyed, our behavior will be destructive. If our experience is destroyed, we have lost our own selves.”

How the media shapes our interpretation affects not just our beliefs and responses, but our perceptions of self and our role in society. If the media’s interpretation no longer aligns with our experience, the conflict can generate self-destructive behaviors.

In other words, mass media interpretations can create a social schizophrenia that can lead to self-destructive attitudes and behaviors.

Social Analysis of TV

By its very nature as a mass shared experience, popular entertainment is fertile ground for social analysis.

Here’s a common example: what does a child learn about conflict resolution if he’s seen a thousand TV programs in which the “hero” is compelled to kill the “bad guy” in a showdown? What does that pattern suggest, not just about the structure of drama, but about the society that creates that drama?

Analyzing entertainment has been popular in America since the 1950s, if not earlier. The film noir of the 1950s, for example, was widely deemed to express the angst of the Cold War era. Others held that the rising prosperity of the 1950s enabled the populace to explore its darker demons—something the hardships and anxieties of the Depression did not encourage.

Many believe the Depression gave rise to screwball comedies and light-hearted entertainment featuring the casually wealthy precisely because these were escapist antidotes to the grinding realities of the era.

Even television shows that were denigrated as superficial in their own time (for example, Bewitched in the 1960s) can be seen as politically inert but subconsciously potent expressions of profound social changes: the “witch” in Bewitched is a powerful young female who is constantly implored by her conventional husband to conform to all the bland niceties of a suburban housewife, but she finds ways to rebel against these strictures.

Laing saw the potential conflict between what we experience and how we’re told to interpret that experience not just in social terms but in psychiatric terms: such splits open a gulf that can lead to a form of schizophrenia.

Diagnosing Our Disease with TV

What can we make of the popular TV series of the present era? What do they say, beneath the surface, about American society?

I contend that popular TV expresses three key aspects of U.S. society and economy that are at odds with the core idealized values espoused in civic classes and the media. The three idealized values are:

1. America is a meritocracy—selections, admissions, etc., are based on the candidates’ merits

2. Anyone can get ahead if they get an education and work hard

3. America is the wealthiest nation on earth in terms of opportunity, fairness and capital

TV expresses three aspects that confound these idealized values:

1. Life is a game in which the winner takes all

2. The opportunity to “get ahead” via conventional means—getting educated, working hard, etc.—is a joke; only those who skirt conventions and the law get rich

3. Life is a tortuous endurance course where those in charge demand the cruel and the impossible

Winner-Take-All Talent Shows

Let’s start with the genre that has been a dominant force in American TV since the 2000s: the winner-take-all talent show (reality and game shows).

The long-running Survivor series, for example, was a winner-take-all contest of physical prowess and political guile, while the many programs staging singing/dancing contests (American Idol, etc.) put entertainment skills to the competitive test. A wide range of other entries stage competitions in cooking, entrepreneurship, losing weight, negotiating obstacle courses, and so on.

What interpretations of our experience do these highly competitive winner-take-all reality shows promote?

We could start with the fact that the stars (other than the hosts/judges) are apparently ordinary “every man/woman” Americans, i.e. people not unlike us. Watching them, it is not too much of a stretch to imagine ourselves on stage, in the kitchen, etc., trying to impress the judges with our talents. It’s easy to identify with the contestants.

These shows enable us to vicariously experience the fantasy that we, too, could be on national TV and could win the accolades of the judges and fans and be the winner who takes it all.

This natural empathy with the temporarily famous with whom we can vicariously share the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat is clearly tapping a deep cultural desire to taste celebrity and the implied financial rewards of winning in an increasing winner-take-all society/economy.

Could the financial/political marginalization of the average citizen and the widening gulf between the typical household and those at the top of the fame/wealth pyramid have something to do with this fascination for winner-take-all competitions on the public stage?

Since there have been game shows on TV for decades, it could be argued that this proliferation of winner-take-all contests is nothing new. But this fails to account for the difference between a game show in which the correct answer is a fact and the subjective votes of judges, other players and the audience that count in winner-take-all contests.

I would argue that this recent explosion of competitions (“modern gladiator,” anyone?) is an expression of deeply held shared cultural values: we accept that ours is a highly competitive society, and that it is becoming even more so as the top “winners” skim the vast majority of the winnings (media visibility, wealth, adulation, social status. etc.), leaving a few morsels for the top 5% and nothing but crumbs for the bottom 95%.

But these TV programs also project the fantasy that our fight-to-the-figurative-death society is still a meritocracy—the best guy/gal wins, as judged by “experts” (or celebrities claiming expertise; the judges’ expertise is structured to be unassailable, just like all the other “experts” in our society).

But if we can’t win it all on merit, there is an alternative way to win: display superior political guile or greater popularity with the audience. (Interestingly, this echoes the coliseum audiences of the late Roman era, who also had some sway over who lived to fight another day on the choreographed battlefield below.)

Perhaps this helps explain our collective obsession with celebrity and the many measures of popularity available to everyone now—Instagram, Facebook likes, Twitter followers (for sale in lots of 10,000), Klout scores, and so on.

In other words, as success in the real world grows increasingly distant, vicariously competing and “winning it all” becomes very compelling. Rather than deal with the vast injustices of our system, we cling to the idealized norm that meritocracy matters, even as “winning” in real life is increasingly a game of cronyism, guile, gaming the system, misrepresenting the truth, etc.

And so we thrill to these play-acting displays of meritocracy in action, as it confirms our cultural value system that that despite the predations of Wall Street and Washington, merit still counts.

And when all else fails, we have a fallback source of identity and “winning”—our popularity. And if we don’t have enough of our own, then we can share vicariously in the popularity of TV show winners and celebrities who have reached the pinnacle.

This is the core message of an interesting and erudite half-hour talk on celebrity given by Games of Thrones actor Jack Gleeson:

“During a recent visit to the Oxford Union, Gleeson took the opportunity to dismantle the ‘religious hysteria’ of celebrity worship with an appropriately epic rant, breaking down the economic, psychological, and sociological catalysts for public reverence of celebrities and their negative impact on society as a whole.”

Gleeson draws upon a number of intellectual sources (Weber, Baudrillard, et al.) in his discussion of the contemporary culture of celebrity, and concludes that celebrity fills the void left when development of an authentic self is stunted.

The parallel with Laing’s “lost self” is striking.

In effect, when the opportunities for developing an authentic self have been reduced to popularity, public visibility and the status that flows from these forms of recognition, then the worship of celebrity and the aching desire for a moment in the spotlight become rational substitutes for a True Self.

As these wispy contingencies can never form an authentic selfhood, even those who do “win” the competition for celebrity are ultimately dissatisfied and disillusioned.

My conclusion: the popularity of competitive winner-take-all TV programs reflects the paucity of opportunities for selfhood and the substitution of celebrity worship for the difficult task of forging an independent identity in a society that marginalizes all but the top players.

If this isn’t a form of cultural schizophrenia, then what exactly is it? The claim that this is all just good clean fun is absurd, as is the claim that it’s perfectly healthy to sacrifice one’s identity in a competition for recognition that 99.9% of us are sure to lose.

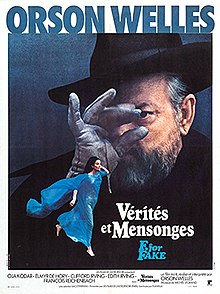

is an unusual film that splits audiences into two camps without breaking a sweat: those who absolutely love it and think it’s an unheralded masterpiece, and those who utterly loathe it (Check out Amazon reviews

!) A third and far larger category would be comprised of everyone who’s never even heard of this odd little gem in the first place. Back in the early 80s, when super rare cheap to license cult films would often appear on some schlocky video label long before some mainstream films became available Putney Swope

would often show up in the “Midnight Movies” or cult films section of video rental shops. After that it more or less disappeared until it came out on DVD. Every once in a while it’s on TV, too, but it’s still, sadly, Putney Swope is not a widely known film.

I thought it was an incredible masterpiece. I was stunned by it. I laughed out loud. I sobbed. It was amazing. It was profound and symbolic of everything! Then again, the first three times I saw the film I was ridiculously high on LSD and I watched it over and over again, by myself, three times in the same night!

that would be difficult to try to describe here. The film is mainly in black and white, but the commercial parodies are in color. Antonio Fargas Jr. (“Huggy Bear” on Starsky & Hutch) has a memorable role as “The Arab,” Putney’s Muslim advisor and prankster Alan Abel is also seen in a cameo role. Putney Swope

has great lines like “Anything that I have to say would just be redundant”; “A job? Who wants a JOB?”; and “Are you for surreal?!” that have been quoted over and over again (at least in my house). The US president and his wife are played by midgets who engage in a threesome with a photographer. There is a Mark David Chapman-type weirdo hovering around. It’s hard to describe, you really just have to see it. I think Putney Swope

is one of the great, great, great American counterculture films of the 1960s. One day. I predict confidently, it will be seen as the equal to Easy Rider or Five Easy Pieces. I’m surprised that French cinemaphiles haven’t discovered it yet… but they will. They will.

DVD on Amazon) but DO watch the first scene up to the point where Putney takes over the advertising agency. If that doesn’t make you want to watch the rest, I can’t do much for you…