Why Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind Remains Unforgettable

By Matt Zoller Seitz

Source: RogerEbert.com

Despite its gently bummed-out vibe, “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” is a sneakily powerful film. It’s so affecting, in fact, that I get a little sad just thinking about the story and characters. Even though I saw “Eternal Sunshine” twice in a theater when it came out and put it on my 2004 Top 10 list, I only revisited it once more after that (to be interviewed for a video essay that, as far as I know, is no longer available online) and haven’t watched it since. It’s not just the story itself that’s piercing; it’s the film’s visualization of memories being destroyed, which hits harder now after seeing so many older friends and relatives (including my mother) succumb to Alzheimer’s disease. It’s a truly great film that can be endlessly appreciated and analyzed for what it’s actually about even while it acquires secondary meanings.

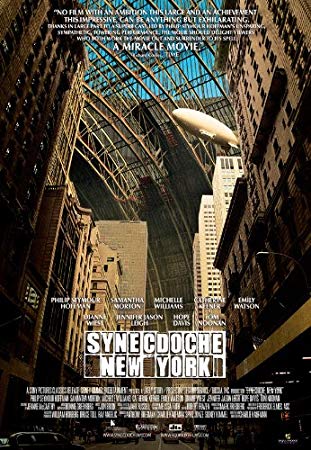

“Eternal Sunshine” is the most perfect film ever made from a Charlie Kaufman screenplay, although Kaufman’s self-written directorial debut “Synecdoche, New York” is an altogether greater, or at least more grandly ambitious, work. Michel Gondry’s decision to shoot almost the entire film in a handheld, quasi-documentary style and have all the special effects appear to have been accomplished in-camera (i.e. through trickery on the set itself, in the manner of a filmed stage production) even when they were digitally assisted doesn’t just sell the idea that everything in the story is “really happening” even when it’s a memory: it blurs the line between what’s real and what’s remembered, an integral aspect of Kaufman’s script that informs every line and scene. The “spotlight” effects created by swinging flashlights on dark streets and in unlit interiors are especially disturbing. When the characters run or hide in those sorts of compositions in sequences, the film boldfaces its otherwise subtly acknowledged identity as a science fiction movie. Past and present (and possible future) lovers Joel Barish (Jim Carrey) and Clementine Kruczynski (Kate Winslet) might as well be rebels in a Terminator film, scampering through bombed-out panoramas and trying not to get zapped by a machine.

Star Jim Carrey was no stranger to dramatic roles by that point in his career, having starred in the media satire “The Truman Show,” the Andy Kaufman biography “Man on the Moon,” and the 1950s-set romantic thriller “The Majestic” (by “The Shawshank Redemption” director Frank Darabont, largely forgotten but worth a look). But his performance as Joel Barish (rhymes with perish) stands apart from everything else he’s done because of its staunchly life-sized approach. It’s a performance as a regular guy that’s entirely free of movie star egocentrism, unflatteringly (or perhaps just unselfconsciously) depicted from start to finish. It’s not easy to forget all the classic Carrey slapstick gyrations that preceded it, and that made him one of the most bankable stars of the 1990s, but somehow you do. He even looks different in the face, somehow. If I’d gone into it not knowing it was him, I might’ve thought, “Who is that actor? He’s excellent, and he looks kinda like Jim Carrey.”

Kate Winslet, who became an international star with Peter Jackson’s “Heavenly Creatures” and a superstar with “Titanic,” established herself as a bona fide character actress in this film. She inhabited Clementine so completely that she unknowingly perfected a type: The Manic Pixie Dream Girl, as per Nathan Rabin’s wonderful phrase describing a woman who “exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures.” I don’t think that’s an entirely accurate description of Clementine as a person; with a bit of distance, she seems more like somebody with undiagnosed mental illness, and Joel is probably right there with her. But it does describe how the role echoed throughout time and through other films and TV shows (including “Elizabethtown,” the film Rabin was reviewing when he coined the phrase, and that happens to costar “Eternal Sunshine” cast-member Kirsten Dunst). There’s no denying the effect the performance had on future movies, which served up endless variations on Clementine.

Gondry’s style creates an analogy for what happens when a person’s memories begin to disintegrate or disappear, in the all-over, “global” sense (Alzheimer’s), as well as for the fleeting universal experience of struggling to remember a name, or some aspect of a dream, and somehow managing to grasp a sliver of it, only to see it slip away and vanish.

The movie also somehow captures that awful knowledge that the personal dramas which consume us go unnoticed by almost everyone else. When it came out, the movie felt so immediate that it was as if you were seeing something that was actually happening, out in the physical world. It still feels like something that could happen because of how it’s lit and filmed. The action seems to have been captured entirely in real locations even when the actors are on sets. The locations tend to be unglamorous, with the notable exception of the beach at Montauk where Joel and Clementine first met (there’s no way to make a beach seem anything less than majestic). The ordinary magic that constantly happens inside each of us – the staggeringly complicated interplay between present-tense observation and interactions; the stabbing intrusions of memory, fantasy, and trauma – contrasts against boringly regular urban and suburban settings that seem to have been chosen because they are the human equivalent of the featureless mazes where rodents of science reside. When Joel and Clementine race through memory spaces where Joel has hidden memories of Clementine to prevent their erasure, they scamper and stop, twist and change direction. They’re people in a mouse-maze.

There’s also a fascinating matter-of-factness to the way the film presents the interactions of Joel and Clementine and the (largely unseen) team of memory-erasers (headed by Tom Wilkinson, and including Dunst, Mark Ruffalo, and Elijah Wood; what a cast!), as well as the way the film un-peels the layers of casual corruption surrounding the process by which memories are destroyed. When you have access to a memory erasing machine and no legal or ethical oversight, the tech is bound to be abused. Is there even an ethical way to use it? Is it right to simply erase something traumatic from a person’s brain? Is it better than teaching the person how to process, understand, and transcend trauma?

There’s a scene at the end of 1981’s “Superman II” where Superman erases Lois Lane’s memory with a super-kiss to protect his secret identity as Clark Kent. The moment was viewed by most audiences at the time as a fairy tale flourish, along the lines of Superman turning back time to save Lois at the end of the first movie. Today it would be considered a non-consensual mental assault, like a roofie. “Eternal Sunshine” sometimes plays like a speculative drama about what would happen if it were possible to replicate Superman’s kiss and turn it into a service that people could pay for. No good could come from such a thing, which is a sure sign that some company out there is hard at work inventing it while its CEO chases billions in startup money from venture capitalists.

A crude version of the necessary technology has existed for decades. The indiscriminate electroshock therapy that was so common in mental hospitals in the middle part of the 20th century, and that often reduced patients to blankly smiling shells of their former selves, became more precisely targeted, to the point where the procedure is now considered an ordinary part of treatment. Ten years ago, scientists figured out by studying mice how to identify the places in the brain where traumatic or negative memories are kept, and “eradicate” them and/or associate them with pleasure. “In essence,” summed up a piece about the process in The Guardian, “the mice’s memory of what was pleasant and what was unpleasant had been reversed.”

The structure of the film is a rich object for study in itself. The very essence of “Eternal Sunshine” is analogous to the unstable process of remembering: remembering the order of events in a story, or the events in one’s own life. Or struggling to remember what happened. Or which thing happened first. And which thing happened after that? Did another thing happen third, or fourth, tenth? Did any of it happen, period? Are you superimposing your fantasies about who was at fault, and who did what to whom, onto events that were factual, and that could be proved or disproved in an objective record, had anyone thought to keep one? The record-keepers records might be faulty, too, or invested in lying or omitting. The movie is kaleidoscopic in its account of how things are remembered, misremembered and forgotten. The opening of the film could also be its ending, and its ending feels like a new beginning. The mouse remains stuck in the maze. When walls and corridors are deleted, and only blank space remains, the mouse struggles to remember the maze.