By Ian Cullen

Source: Scifi Pulse

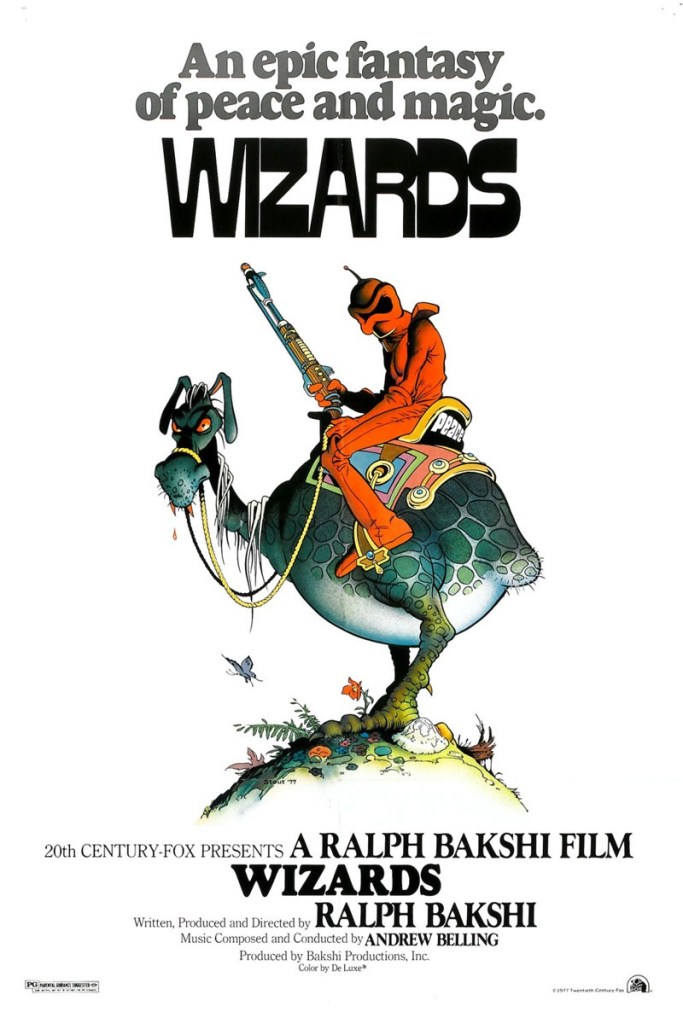

The animation in this film is a weird psychedelic hodgepodge of various styles. It seems both very cool and experimental at the same time.

Synopsis: In Wizards After the death of his mother. An evil mutant wizard Blackwolf discovers some long-lost military technologies. Blackwolf claims his mother’s throne, assembles an army, and sets out to brainwash and conquer Earth. Meanwhile, Blackwolf’s gentle twin brother, the bearded and sage Avatar calls upon his own magical abilities to foil Blackwolf’s plans for world domination — even if it means destroying his own flesh and blood.

The Story

Wizards begins with the destruction of the earth via a nuclear explosion. After several thousand years. The few survivors of humanity have become mutants and hide in the shadows. But from the ashes the fae folk of long-forgotten earth is reborn. They live in peace and tranquility for many thousands of years until their Queen gives birth to twin Wizards. Avatar a goodly and kind Wizard and his evil brother Blackwolf.

When their mother the Queen dies. The two brothers fight and Blackwolf is defeated by Avatar and journeys to form his new kingdom of Scorch. While in exile for 3000 years. Blackwolf sends his demonic forces out to search the earth for old technologies that he can use to defeat the forces of good and ultimately defeat his brother.

Meanwhile, in Montagar Avatar and his girlfriend, Elinore are blissfully unaware of Blackwolf’s plans until one of his soldiers Necron 99 attacks and kills their President.

Voice Acting

The acting throughout this films is really solid. Bob Holt is excellent as the kindly Wizard Avatar who justs wants to live a peaceful and hassle-free life. His interactions with Elinore (Jesse Welles) are a lot of fun and full of innuendo, which is something the film features a lot of. Richard Romanus puts the swashbuckler in Weehawk the soldier Elf who will fight to the death to defend his lands.

We also get Mark Hamill in perhaps his shortest animated role ever as Sean the ill-fated king of the Fairie folk. No sooner as he introduces himself. He gets wasted by one of Blackwolf’s soldiers.

Finally, special mention must go to Steve Gravers who puts in a great performance as the evil Wizard Blackwolf.

Animation

Directed and produced by Ralph Bakshi who is better known for his more adult-orientated animated films and series such as ‘Fritz The Cat’. ‘Wizards’ was supposed to be Bakshi’s first attempt at doing something for a family audience. Although we’d have to agree to differ on that front given that within the first five minutes we meet three fairy prostitutes. And Then we get Elinore sporting curves that would make most glamour models jealous.

The animation in this film is a weird psychedelic hodgepodge of various styles. It seems both very cool and experimental at the same time. I particularly loved the Rotoscoping effects that are used fairly heavily in the film. Especially when it came to the use of it with old world war 2 footage of tanks and planes. For its time, which was the late 70s. The animation in this movie was likely cutting edge. And I think it holds up pretty well considering.

Overall

Some of the themes and storylines within this film are probably more for the older kids than for younger viewers. How Bakshi managed to get a PG rating for this film will forever be a mystery. Especially given how little Elinore is wearing. Added to which the debate about Technology versus Nature and Magic while fun would probably go over the heads of younger viewers.

The film was made in a time where things like duck and cover were still fresh in the minds of most adults that saw the film at the time. If anything it was a film warning about the threat of nuclear war and it was very on the nose in that respect. I was about 12 when I first saw this movie as a video rental back in around 1982 and it stuck in my memory because this review is based on only my second viewing of the movie since back then.

That said though. The more mature version of me did spot a few contradictions in the film. The ones that stand out are to do with Avatar and his land of Montagar where technology is supposed to be outlawed. In the scene that establishes Avatar, we see him conjure up a jukebox. And later on as we get to the final battle. He uses a gun. Now back when I was 12 I wasn’t to bothered by this. But the grown-up me thinks Avatar is a hypocrite and a cheat for breaking his own rules.

Overall though. Despite those two issues I spotted. It is still quite an enjoyable film with some killer 70s funk and prog-rock guitar licks making up a killer soundtrack.

Watch Wizards at Internet Archive here: https://archive.org/details/y2mate.combernievstrumprzlyugsut7q360p