By Roger Ebert

Source: RogerEbert.com

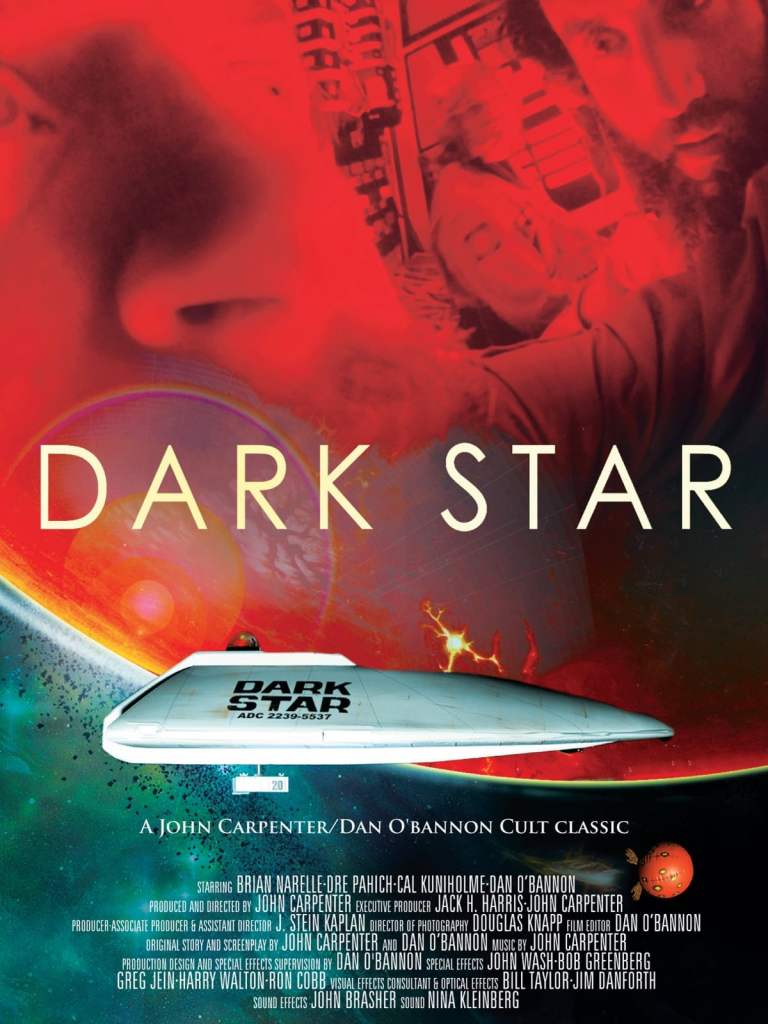

“Dark Star” is one of the damnedest science fiction movies I’ve ever seen, a berserk combination of space opera, intelligent bombs, and beach balls from other worlds. It has a checkered history. It began as a student project by John Carpenter (later to direct “Halloween“) and Dan O’Bannon (later to write “Alien“), and grew over a period of time and expanding budgets into a full-length film.

It was finished some four years ago, before “Star Wars,” and might have had a big success as a cult film if its original distributor hadn’t been so chicken-hearted that he dumped it in a string of Southern California drive-ins and then pulled it out of commercial release. As it is, “Dark Star” has found audiences on the campus and revival circuits, has been a hit here at Facets Multimedia, and, at last, is having its first commercial run at the Three Penny Cinema.

It was finished some four years ago, before “Star Wars,” and might have had a big success as a cult film if its original distributor hadn’t been so chicken-hearted that he dumped it in a string of Southern California drive-ins and then pulled it out of commercial release. As it is, “Dark Star” has found audiences on the campus and revival circuits, has been a hit here at Facets Multimedia, and, at last, is having its first commercial run at the Three Penny Cinema.

The movie’s best sequence centers around the care and feeding of the pet alien they’ve taken on board (a sequence that O’Bannon may have drawn on for the original screenplay of “Alien”). The “Dark Star’s” onboard alien looks like a plastic beach ball with claws, and has a nasty way of sneaking out of sight; a crew member chases it into an elevator shaft and gets himself into a very tight spot. (The elevator sequence looks suspiciously as if it were filmed on the floor of a horizontal hallway photographed to look like a vertical shaft.)

Otherwise, life just sorta drifts past, until a chain of accidents leads to a situation where a bomb does not detach from the ship as planned, and will explode in 24 minutes, blowing the “Dark Star” to smithereens. The bomb cannot be disarmed because, intelligent little devil that it is, it’s convinced that it has a mission to self-destruct.

The movie’s best sequence centers around the care and feeding of the pet alien they’ve taken on board (a sequence that O’Bannon may have drawn on for the original screenplay of “Alien”). The “Dark Star’s” onboard alien looks like a plastic beach ball with claws, and has a nasty way of sneaking out of sight; a crew member chases it into an elevator shaft and gets himself into a very tight spot. (The elevator sequence looks suspiciously as if it were filmed on the floor of a horizontal hallway photographed to look like a vertical shaft.)

Otherwise, life just sorta drifts past, until a chain of accidents leads to a situation where a bomb does not detach from the ship as planned, and will explode in 24 minutes, blowing the “Dark Star” to smithereens. The bomb cannot be disarmed because, intelligent little devil that it is, it’s convinced that it has a mission to self-destruct.

And so, in an incredible and hilarious scene, a crew member floats out into space, confronts the stubborn thinking bomb, and uses pure logic in an attempt to reason it out of exploding. The strategy: If the bomb can be convinced it has no evidence that the universe really exists, then how can its instructions be valid?

This is a fun movie, and a bright and intelligent one. It bears few signs of having been made on a low budget, and the special effects are reasonably slick. And it has a mercifully low-key comic approach; many satiric comedies by young filmmakers are frantic and overwrought, but this one is wry, laid back and fond of its situations. And on the same program is “Hardware Wars,” a short subject starring steam irons, pop-up toasters and other kitchen appliances in outer space.