Category Archives: Saturday Matinee

Saturday Matinee: Detective Dee: The Four Heavenly Kings

By Andrew Skeates

Source: Far East Films

Tsui Hark returns for a third go around in his fantasy blockbuster franchise, sending the titular Dee on another eye-boggling, mind-warping, wuxia-infused adventure. While the first instalment saw Andy Lau take on the title character, the first follow up, ‘Rise of the Sea Dragon’, saw a younger version of Dee (now played by Mark Chao) muddle his way through an assortment of fanatical situations. ‘The Four Heavenly Kings’ is a direct follow on from ‘Rise of the Sea Dragon’, with Chao and many of the core cast returning for another adventure which may just be the best in the series.

Due to his exploits in ‘Rise of the Sea Dragon’, Dee is rewarded the coveted Dragon Taming Mace: a near mythical and indestructible weapon. So coveted it is, that many a nefarious foe want to get their hands on it including Empress Wu (Carina Lau) who hatches a plan to steal it and discredit Dee using a band of mystical warriors. Coupled with the resurgence of a once deadly spiritual tribe, Dee soon finds all is not what it seems as sorcery weaves it evil way, and he and his fellow Bureau colleagues attempt to uncover the conspiracy and battle an ever increasing assortment of fantastical creatures and foes.

Much like the first two Dee flicks, ‘The Four Heavenly Kings’ is an often breathless fantasy blockbuster that doesn’t skimp on the wuxia action, CGI wonderment and imaginative scenarios. These days Tsui Hark is happy to play in the big budget, CGI sandbox and while his recent films have been a bit hit or miss, the ‘Detective Dee’ flicks have arguably been his most enjoyable blockbusters of late. While ‘Mystery of the Phantom Flame’ and ‘Rise of the Sea Dragon’ could be all over the place in tone and plotting ‘The Four Heavenly Kings’ finds Hark on more assured ground. Sure there is still a fair amount of convoluted plotting and subplot/secondary character development a-go-go which takes a while to digest as the narrative often rockets along, but on the whole this entry flows coherently.

Dee’s cohorts (Lin Gengxin and Feng Shaofeng) get fully fleshed character arcs and are just as integral to the plot and action as the lead, with Feng Shaofeng (as General Yuchi) all but stealing the film. This unfortunately means Dee feels somewhat like a supporting character in his own film but the team dynamic is a nice approach to this threequel and keeps the viewer guessing and often surprised as to where the narrative is going. While the film is packed with playful energy, energetic set-pieces and a good amount of silliness, ‘The Four Heavenly Kings’ also packs in a fair bit of menace, not least when the vicious Wind Warriors show up. A truly threatening foe, they add menace and bite to what is essentially a cartoon blockbuster, Hark wringing out some genuine tension every time they appear on screen.

As with the other Dee instalments (and most of Hark’s recent output), this entry is packed with CGI ingenuity which leads to some truly creative scenarios and characters. For the most part the CGI works (save for the odd wonky bit here and there) and blends into the environment and practical action well. Hark certainly can’t resist packing in as much CGI inventiveness as he can but come the finale it certainly works to deliver some truly eye frazzling action: complete with giant gorillas, squids and some sort of colossal demon made up of eyeballs!

If one isn’t a fan of this type of CGI laced, fantasy blockbuster then one is probably not going to get along with ‘The Four Heavenly Kings’ but if one is (and enjoyed the previous jaunts with Dee) then there is a lot of fun to be had here. Tsui Hark delivers a wickedly fun fantasy romp full of wondrous fight action and flights of fancy.

Watch the film on Tubi here: https://tubitv.com/movies/619638/detective-dee-the-four-heavenly-king

Saturday Matinee: A Midnight Clear

By James Berardinelli

Source: ReelViews.net

December 1944 in the Ardennes. The Battle of the Bulge is beginning. The snow is falling gently, coating everything in white. It’s here that the members of a small American Intelligence squad find themselves holed up in an abandoned house under orders from their commander, Major Griffin (John C. McGinley). Their mission: watch, listen, and report back if there are signs of enemy activity. The squad’s leader, Sgt. Will Knott (Ethan Hawke), is doubtful about things from the beginning. He is in command because he has survived thus far while six others haven’t. The oldest soldier, ‘Mother’ Wilkins (Gary Sinise), has suffered a mental breakdown following the long-distance news of the stillborn death of his child. The other four – Bud Miller (Peter Berg), Mel Avakian (Kevin Dillon), Stan Shutzer (Arye Gross), and ‘Father’ Mundy (Frank Whaley) – do their duty, although not all of them are happy about it.

There’s a group of Germans out in the forest – seven of them, as it turns out. Hitler’s war has so depleted the Germany army that they’re left with “old men and boys.” They’re tired and scared and, like many Axis soldiers in Europe, recognize that hope has fled. They don’t want to die so they seek an alternative to fighting. Surrendering to the Americans doesn’t seem like a bad one, as long as they can make it look like they were taken after a battle. The first challenge is to conquer the language barrier, something they attempt not with bullets but by stoking the Christmas spirit. After a tree, a few carols, and an exchange of gifts, the Germans and Americans are able to regard one another with something closer to trust than hostility. Until, of course, it all goes wrong. In war, it seems, that almost always happens.

A Midnight Clear is adapted from the novel of the same name by William Wharton. It is not based on a true story – there are no records of American and German soldiers fraternizing around Christmas during World War II – not in 1942, 1943, of 1944. Wharton may have been inspired in part by an incident from World War I, however. On December 25, 1914, the so-called “Christmas Truce” occurred – a series of unofficial cease-fires along the trenches of the Western Front. French, German, and British soldiers put aside their differences to talk, sing, and toast the season. (The 2005 film Joyeux Noel dramatized this.) There’s an echo of that in A Midnight Clear. Fiction, however, follows history. Once the holiday was over in 1914, many of the men who shook hands killed one another. In A Midnight Clear, the outstretched hand is ultimately cut off. Human nature is a fickle thing – the impulse to reach out to another is counterbalanced by a cold-hearted bloodthirstiness.

A Midnight Clear is a war story but it’s not like any other war story ever made. The characters (well, most of them at least) are nuanced. The situations are fluid and ambiguous. And there are no big battles. At one point, a character remarks that he doesn’t like this kind of war. He doesn’t want to meet the enemy. He wants to shoot them dead from afar, never knowing a thing about them. One of the most impactful aspects of A Midnight Clear is that when the time comes to kill, the targets are no longer faceless.

A Midnight Clear is powerful without being overbearing. It emphasizes the chaotic and nonsensical aspects of war without dragging the viewer into the trenches and burying him/her in mud. The movie is sad in a way that even a powerhouse picture like Platoon didn’t manage. The only villain here is circumstance, unless you count John C. McGinley’s Major Griffin, who is thankfully kept in the background except at the beginning and the end.

Speaking of McGinley, he represents one of two missteps on the part of Keith Gordon’s otherwise fine effort as a writer/director (this was his second film behind the camera). Griffin is written as a two-dimensional asshole and McGinley portrays him with cartoonish fluency. In a film where every other character has as many facets as a well-cut gemstone, Griffin feels like he stumbled into the wrong movie.

The other problem relates to a flashback detailing how the four youngest members of the group lost their virginity. A young woman named Janice (Rachel Griffin) opts to give herself selflessly to these soldiers rather than commit suicide (she’s despondent after learning of the death of her fiancé overseas). It’s a bit of wish-fulfillment that strikes a wrong chord no matter how hard Gordon tries to make the situation sympathetic.

The acting is uniformly strong, featuring a group of performers at the beginning of what would be long and productive careers. A little-known Ethan Hawke (with a previous role in Dead Poets Society) shows the charisma that would make him the go-to actor for many serious-minded directors. Gary Sinise, several years pre-Lt. Dan, makes the psychologically wounded Mother a suitably complex individual. Also featured are Peter Berg, Kevin Dillon, Arye Gross, and Frank Whaley. This may not be a “who’s who” of future A-list stars but it’s a strong roster of men who would become known for their ability to flesh out characters.

The typical movie set in and around Christmas embraces the mood of the season: Peace on Earth and Goodwill to All People. A Midnight Clear has a sharper and less idealistic perspective of things. Viewed through the lens of war, the absurdity of human nature is laid bare. We see the good, the bad, and the ugly – all packaged together in events spanning a few days leading up to December 25. It’s a reminder, as if any is needed, that, despite the birth being celebrated at Christmas, humankind is still very much in need of salvation.

Watch A Midnight Clear on Kanopy here: https://www.kanopy.com/product/midnight-clear

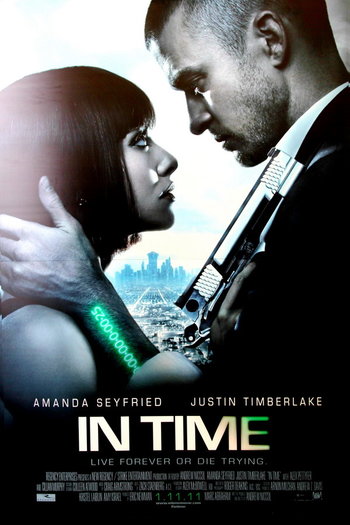

Saturday Matinee: In Time

A thought-provoking sci-fi thriller set in the future that taps into some of the most troubling inequities and problems of our era, the lack of time.

By Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat

Source: Spirituality and Practice

The best science fiction always uses some trend or policy of the present as a foundation and projects it into the future with a picture of some possible results. Through this glimpse of tomorrow, we can ponder anew the spiritual or philosophical ramifications of what we are doing today. In The Adjustment Bureau, we were given a chance to assess the idea of free will or the alternative of following a plan mapped out by God. In Gattaca the idea of genetically engineered perfection is explored. Writer and director Andrew Niccol who wrote and directed the latter thriller is also at the helm of this thought-provoking sci-fi drama that has many resonances with today’s world.

The Preeminence of Time

A search on Google for “time” yields more than 11 billion hits whereas there are fewer than 3 billion hits for “money” and 241 million hits for “sex.” Time is very much on our minds and at the hub of our concerns. We speak of “having” and “saving” and “wasting” time but we never seem to find a way of “conquering” it. We are caught up in the obsessive-compulsive need to make the most of the time we have each day. Pagers and cell phones are taken everywhere. We don’t want to miss a moment of connection.

In Time is set in a future dystopia where living zones separate the rich from the poor. Will Salas (Justin Timberlake) lives in a ghetto zone with his mother Rachel (Olivia Wilde). She looks very young since all aging stops at 25.

Will works in a factory and she has a job as well, but still it is hard to make ends meet. Time in this society is literally money. Each person has a timer on his or her arm and at 25 you are given one year of free time after which you die — unless you can find a way to get more time. Wages are doled out in days of added longevity. All expenses (rent, a cup of coffee, clothes, phone calls) are paid for with time and scanners are used to deduct the time for the purchase. The biggest fear in the ghetto is that your time will run out unexpectedly. That is exactly what happens to Will’s mother.

Time Is Strange

“Time is stranger and deeper than anything else in our lives.”

— Jacob Needleman

The biggest dream in the ghetto is acquiring a surplus of years and the prospect of immortality. When Will saves a young man with a century on his clock, the fellow gives the years to him and then commits suicide. An intrepid “Timekeeper,” Raymond Leon (Cillian Murphy), is convinced that Will stole the years from the dead man. He launches a man hunt for him. Also hot on Will’s trail are some nasty time thieves.

Caught in Time

“Time is the element in which we exist. We are either borne along with it or drowned in it.”

— Joyce Carol Oates

Will begins a daring journey into the zone for the time rich called New Greenwich. After winning more than a millennium at a casino, he meets Sylvia (Amanda Seyfried), the daughter of Philippe Weis (Vincent Kartheiser), an immensely wealthy and powerful banker who has been exploiting the poor by making high interest time loans. A believer in “Darwinian capitalism,” he’s stored up enough years to be immortal. But Sylvia thinks there must be more to life than the favored existence she knows. She is intrigued by Will’s wild ideas about changing the system which favors the rich over the poor and allows many to die so a few can be immortal. After he takes her hostage when the Timekeeper is closing in on him, Sylvia doesn’t take very long to pledge her allegiance to what becomes their own mutual crusade. They begin robbing time banks and giving time to the poor and the down-and-out.

In Time is a winning sci-fi thriller that taps into some of the troubling problems of our era, such as the view of time as money, the growing gap between the rich and the poor, and all the ways that we waste time and fail to value every moment. It is also a meditation on the healing and restorative medicine of generosity and sharing. Writer and director Niccol has given us a cautionary tale about the possible future consequences of class consciousness, the high cost of trying to stay young or live forever, and the need for something more meaningful than just spending time to get ahead of the game.

Saturday Matinee: Monopoly – Follow the Money

By Stuart Bramhall

Source: The Most Revolutionary Act

Monopoly – Follow the Money

Directed by Tim Gielen (2021)

Translated by Vrouwen voor Vrijeid (Women for Freedom)

This Dutch documentary attempts to pinpoint the main corporations and individuals responsible for the Covid plandemic.

It begins by examining the key institutional investors that own the vast majority of the global share market. Going company by company, filmmakers reveal that approximately 8-10 institutional investors own 80% of the stock of nearly all global corporations. Some of the smaller institutional investors include mutual and pension funds. However the top three of every corporation they examine include BlackRock* and the Vanguard Group.**

The film looks at the institutional shareholdings of company after company, including Google, Twitter, Apple, Microsoft, Sony, Phillips, Boeing, Airbus, Coca Cola, Pepsi, all the mining companies, all the oil companies, Cargill, ADM, Bayer (the largest seed producer in the world since their acquisition of Monsanto), all the textile and fashion brands, Amazon, Ebay, Master Card, Visa, Paypal, and all the banks, tobacco companies, defense contractors, insurance companies, processed food companies, cosmetic brands and publishers and media outlets.***

In every case, both Vanguard Group and BlackRock are both within the top three institutional investors.

They also own stock in each other’s companies. In fact, Vanguard is the biggest shareholder in BlackRock, which Bloomberg refers to as the “fourth branch of government” because it both advises central banks and lends them money.

We don’t know exactly who owns shares in Vanguard as it’s not a publicly traded company. However we do know that it’s a safe place for many of the most powerful families in the world to hide their wealth (eg the Rockefellers, Rothschilds and British royal family).

The film also explores how wealthy families use nonprofit foundations to shape global politics in their own interest without attracting public attention. The big three featured in the film are George Soros’s Open Society Foundation, the Clinton Foundation and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

All these rich and powerful elites meet at the World Economic Forum in Davos Switzerland every January and mingle with world leaders and significant non-profit groups, such as Greenpeace and UNESCO.

Chairman and founder of the WEF is Klaus Schwab, a Swiss professor and businessman. In his book, The Great Reset, he states that the coronavirus is a great “opportunity” to reset our societies. According, to Schwab, our old society must switch to a new one because the consumption society the elite has forced on us is no longer sustainable. Under the new society he proposes, people will own nothing and rely primarily on the state to get their needs met.

*BlackRock, Inc. is an American multinational investment management corporation based in New York City. Founded in 1988, initially as a risk management and fixed income institutional asset manager, BlackRock is the world’s largest asset manager, with $8.67 trillion in assets under management as of January 2021.

**The Vanguard Group, Inc. is an American registered investment advisor based in Malvern, Pennsylvania with about $7 trillion in global assets under management, as of January 13, 2021. It is the largest provider of mutual funds and the second-largest provider of exchange-traded funds in the world after BlackRock’s iShares.

***What this means, In essence, is that a handful of individuals control all public information.

Saturday Matinee: Parasite

Bong Joon-ho delivers a biting satirical thriller about class warfare and social inequality

By Prahlad Srihari

Source: Firstpost.

Bong Joon-ho has always been interested in the mechanics of genre cinema. The South Korean director has made a career of subverting established genres in an intelligent, meaningful manner. In The Host and Okja, he took the creature feature and added socio-political subtext to it. The serial killer thriller, Memories of Murder, highlighted police incompetence in South Korea and the Hitchcockian murder mystery, Mother, revealed the cultural divide between men and women in Korean society.

Fortunes change when Ki-woo falsifies his credentials to land a tutoring job with a wealthy couple, Mr Park (Lee Sun-kyun) and his gullible wife Yeon-kyo (Cho Yeo-jeong). While he teaches their daughter Da-hye (Jung Ziso), he learns that their troublesome son Da-song (Jung Hyeon-jun) also needs help improving his drawing skills. Ever the opportunist, he recommends his sister — not revealing her real identity of course. She recommends her father as a driver after getting the previous one fired by setting him up as a sex fiend. Ki-taek then recommends his wife to take over as housekeeper after a scheme involving the most creative use of peaches since Call Me By Your Name. After their clandestine infiltration operation into the Parks’ lives is complete, the story makes so many intense and unexpected twists and turns, it turns into a whole different beast altogether.

The cast of Parasite deliver performances of exceptional psychological acuity and perverse frivolity. Led by Bong’s frequent collaborator Song Kang-ho, they are sure to conjure the loudest of laughs and the strongest of emotional reactions from their audiences.

Bong brilliantly uses the upstairs-downstairs distinction in the Parks’ house to reveal a socially divided society. And the society is not just divided by wealth but also culture. Bong revisits a familiar theme of the proliferation of American values over traditional Korean ones. The Parks are a Westernised family who live in a sleek, modernist home with white picket fences — and who buy toys and gadgets from the US, exemplifing the upper crust. Ki-taek’s family, meanwhile, lives in a sordid apartment in the basement, where cockroaches thrive and drunkards urinate on their windows. So, with Parasite, Bong tries to bring to light this deep, festering malady at the heart of Korean society.

Parasite offers a cleverly paced, thoroughly entertaining blend of sumptuous visuals and wickedly dark humour. The music too makes the plot twists and revelations hit that much harder.

Despite the cultural and language barriers, Parasite is an unforgettable cinematic experience as it speaks to universal ideas, themes and emotions. If Bong Joon-ho’s style of genre filmmaking hasn’t become an adjective already, it sure is time now.

Watch Parasite on Kanopy here: https://www.kanopy.com/product/parasite-2

Saturday Matinee: From JFK To 911 Everything Is A Rich Man’s Trick

Source: Top Documentary Films

The assassination of President John F. Kennedy lingers as one of the most traumatic events of the twentieth century. The open and shut nature of the investigation which ensued left many global citizens unsettled and dissatisfied, and nagging questions concerning the truth behind the events of that fateful day remain to this day. Evidence of this can be found in the endless volumes of conspiracy-based materials which have attempted to unravel and capitalize on the greatest murder mystery in American history.

Now, a hugely ambitious documentary titled Everything is a Rich Man’s Trick adds fuel to those embers of uncertainty, and points to many potential culprits whose possible involvement in the assassination has long been obscured by official historical record.

Authoritatively written and narrated by Francis Richard Conolly, the film begins its labyrinthine tale during the era of World War I, when the wealthiest and most powerful figures of industry discovered the immense profits to be had from a landscape of ongoing military conflict. The film presents a persuasive and exhaustively researched argument that these towering figures formed a secret society by which they could orchestrate or manipulate war-mongering policies to their advantage on a global scale, and maintain complete anonymity in their actions from an unsuspecting public. Conolly contends that these sinister puppet masters have functioned and thrived throughout history – from the formation of Nazism to the build-up and aftermath of September 11.

The election of President Kennedy in 1960 represented a formidable threat to these shadowy structures of power, including high-profile figures within the Mafia, crooked politicians, and the world’s most influential and notorious war profiteers. Thus, a plot was hatched which would end Kennedy’s reign prior to any chance of re-election, thereby restoring the order and freedoms of these secret societies.

At nearly three and a half hours, Everything is a Rich Man’s Trick examines a defining event of our times from a perspective not often explored. While it may or may not win over viewers who remain skeptical of mass-scale conspiracy, it presents its findings in a measured and meticulous manner which demands attention and consideration.

Saturday Matinee: Midnight Special

Source: Deep Focus Review

People put their faith in the strangest things. Some feel their god will return to cast down judgment on humankind. Others are certain beings from another solar system planted genetic material on Earth to create life. And some believe, or perhaps not, that a flying spaghetti monster lives in the sky. Here’s another one: Folk music history tells us a train called the Southern Pacific Golden Gate Limited ran near Sugar Land prison in Texas, where legendary Blues man Lead Belly heard it passing. He and other inmates believed the train represented some sign of hope that soon they would be set free. Lead Belly later popularized a song about it, called “Midnight Special”, featuring a lyric in which he asks the train to “shine a light on me”. Apart from memorable covers by Harry Belafonte, Bob Dylan, and Credence Clearwater Revival, Lead Belly’s folk song informs the title of writer-director Jeff Nichols’ fourth film, Midnight Special.

People in the film believe some strange things, too. Some of them believe a young boy will grant their way to salvation, while the government believes that same boy is a threat to national security. But more on the specifics later. These belief systems pervade Nichols’ screenplay, a slow-burner infused with soulful character depth and science-fiction underpinnings. Midnight Special has much in common with Nichols’ excellent Take Shelter (2011), about a working-class family plagued by the father’s apocalyptic premonitions. That otherwise grassroots, southern-fried suspenser contains fantastical elements, though really it’s about the extremes people will go to chase what they believe. Nichols has explored similar American spirituality in his other two films, Shotgun Stories (2007) and Mud (2011). Each of his films demonstrates the potential danger inherent to blindly following our beliefs and convictions.

Nichols’ calculated opening demands the audience take time to figure out what’s happening and why, who the good guys are, and in the end, what just came to pass. It’s a picture audiences must feel their way through in the best possible way. An Amber Alert blares across the television screen, a reporter notifying us a young boy named Alton has been kidnapped by a man named Roy. As the shot pulls back, we find ourselves in a motel room with Roy (Michael Shannon, severe as ever) and Alton (Jaeden Lieberher), who, behind an ever-present pair of swimming goggles, reads a comic book by flashlight. Also in the room is a crew-cut man of action, Lucas (Joel Edgerton). They’re waiting until the sun goes down to continue their getaway. Lucas drives fast and without headlights, wearing night vision headgear to see the highway in the pitch dark.

Nichols cross-cuts to things at “The Ranch”—a Texas compound not unlike David Koresh’s Branch Davidians—populated by old-world types in hand-sewn garb. They’re led by a quietly intense organizer named Calvin (Sam Shepard), who wants Alton returned to him. The FBI raids The Ranch and puts everyone on buses to a secure location. They ask questions about Calvin’s people buying guns and about Alton’s kidnapping. A bookish NSA specialist named Sevier (Adam Driver) wants to know about Alton, who came in contact with him, and what they know about the boy’s abilities. And so we must wonder, why so many questions about this boy? The answer: When Alton is exposed to the sun, beams of light shoot from his eyes; he seems to speak in tongues; he can give people visions; in space, satellites meant to detect nuclear explosions spy an energy source emitting from him; he also picks up radio signals in his head.

But what is he? Nichols never answers that question outright. Over time, we learn Roy is Alton’s father, and Lucas is Roy’s friend, and together they’re protecting Alton from The Ranch and the government. All parties concerned feel a great power exists inside the boy and, though they don’t completely understand it, they fearfully pursue and defend him. Soon Alton’s mother (Kirsten Dunst) joins Roy and Lucas, aware of the entire plan. We learn all of Alton’s peculiarities have a hidden encryption, coordinates that point to a certain spot on a specific day. Everything depends on getting him there on time. And gradually, as men from The Ranch get closer to recapturing Alton, and the government goons track down their perceived threat, we get a greater—but not clearer—sense of what might occur if and when Alton arrives at his destination.

Rather than frustrating, that lack of transparency is engrossing, as Nichols drops hints here and there, while he binds us to the often moving, unquestionably engaging proceedings through subtle character work. So what is Alton? He finds great interest reading a Superman comic, so perhaps he’s something like Superman, a powerful alien. Perhaps he’s a messiah sent to protect people at The Ranch. Maybe he’s an advanced form of human with mutant powers, a time traveler, a living weapon, or an inter-dimensional being. Whatever the answer, it’s less important than the real-life descriptions of the humans on Nichols’ journey. His actors carry impressive weight and gravitas, particularly Shannon, who has appeared in each of Nichols’ films. But the entire cast brings substance to their performances, involving the audience in the tense, measured development of the story.

Both narratively and technically, Nichols has used the films of Steven Spielberg and John Carpenter to inform Midnight Special, but not in such a way that it feels distractingly derivative. From the perspective that the film operates as a road movie driving toward some manner of grandiose sci-fi conclusion, the film feels like Close Encounters of the Third Kind; the ending, too, resembles Spielberg’s wondrous 1977 effort. Elsewhere, Starman (1984) comes into play, as everyone who meets Alton gravitates to his kindness, soulful sureness, and power, just as everyone in Carpenter’s film found Jeff Bridges’ alien character a kind of angelic figure. Even the ending seems to combine the finales of these two films, with a touch of E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial. The film also bears some similarity to Tomorrowland, although the association is undoubtedly unintentional. All the while, Adam Stone’s textured 35mm lensing captures familiar lens flares and widescreen compositions from Carpenter and Spielberg that influenced Nichols.

Questions about what happens in its marvelous climactic scenes aside, Midnight Special shines a light on the audience by offering a unique combination of the realistic and out-of-this-world. Nichols develops thoroughly dimensional characters, even among the not-irredeemable “villains” of the story. The director cares about Roy’s heavy brow and Sevier’s sense of unsure awe; with them, he develops intimate moments that effectively resonate further than the sci-fi gimmick. He never overplays the drama, such as a scene in which Alton tells his father not to worry about him. Roy replies, “I like worrying about you.” The understatedness of Nichols’ drama, the poignancy, renders a picture about how people react to what they believe or do not understand. Some embrace it; some fear it. No matter the reaction, Nichols finds a way to represent that through an engaging metaphor in his profoundly affecting and, in many ways extraordinary thriller.

Watch Midnight Special on Hoopla here: https://www.hoopladigital.com/title/14507307