PRISONERS OF THE GHOSTLAND, Leave Sanity at the Door

Nicolas Cage. Sofia Boutella. Sono Sion. Need we say more? Yes.

By Eric Ortiz Garcia

Source: Screen Anarchy

More than 30 years after his first film, Sono Sion has established himself as a brilliant, prolific and chameleonic director.

In the past decade alone, you can find some of his best work: a hilarious tribute to guerrilla filmmaking and 35mm, with yakuzas, samurais and martial arts, Why Don’t You Play in Hell?; brutally violent and sordid films, Cold Fish and Guilty of Romance; dramas alluding to the nuclear disaster in Fukushima, Himizu and The Land of Hope; a crazy hip hop musical, Tokyo Tribe; and an emotional kaiju and Christmas film with catchy rock songs, Love & Peace.

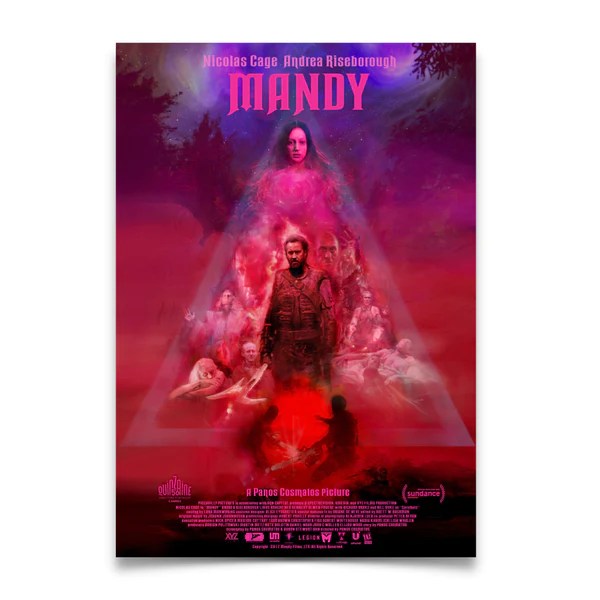

On the other hand, Nicolas Cage became one of the most prolific Hollywood actors, finding in recent years memorable roles in genre cinema that, beyond subversive, are absolutely delirious. Mandy and Color Out of Space are enough to forget his abundant jobs-for-hire.

Considering that, Prisoners of the Ghostland, Sono’s highly anticipated English-language debut starring Cage, is insane. Truly insane.

Sono has excelled in building his own worlds. When I interviewed him in 2015 about Tokyo Tribe, he revealed that he wasn’t interested in using real locations in that city, because he wanted to “make up a whole fake world.” Prisoners of the Ghostland, one of his productions with the biggest budget, isn’t contained in that regard. Its two main universes – or rather, prisons – come to life and are wonderful madness.

Prisoners of the Ghostland is Sono’s Western and his return to samurai cinema, two genres that he feels affection for like his contemporaries: Miike Takashi (Sukiyaki Western Django) and Quentin Tarantino (Kill Bill, Django Unchained). A group that shares influences: Sergio Leone, Ennio Morricone, Sergio Corbucci, Bruce Lee, Fukasaku Kinji, Fujita Toshiya, among many others.

In Sono’s “Old West”, West and East coexist, the mystique of the cowboy and the samurai. In fact, it’s set in “Samurai Town.” The iconic sheriff is an obese, long-haired Japanese cowboy, an Elvis Presley fan. The town’s true “boss”, the Governor (Bill Moseley, in a performance to remember), is a “gringo” with a Southern accent who runs a geisha place. He’s accompanied by his favorite heavy: the skilled samurai Yasujiro, played by Sakaguchi Tak himself, “Bruce Lee” in Why Don’t You Play in Hell? and more recently the protagonist of Crazy Samurai Musashi, the exciting and bloody one-take sequence based on an idea by Sono.

The hybrid and extravagant iconography extends to the town, practically an alternate universe where all kinds of people live together regardless of age (there’s a good number of children). It’s a clash between the traditional and the modern: a classic Western/Oriental town adorned with electronic signs, with interiors worthy of a stylized futuristic movie. Well, the Governor travels in a modern car! It’s the cinema of cool at its most striking expression.

Who better to lead the cast than an actor with a perfect understanding of this type of cinema? Is there a better vehicle for Cage than a film where his character is described as “so cool, so badass”?

The actor has been enjoying himself big time. “Personally I find his stylish performances extremely enternaining,” said Richard Stanley when I interviewed him about the Lovecraftian Color Out of Space, “they say it’s campy and over-the-top, that how can you make a serious but pretty fun movie. That’s just what I love about Nic, he’s capable of being funny and serious at the same time.”

Cage maintains that style in Prisoners of the Ghostland, bringing the classic unnamed antihero to life, although unlike those almost silent figures in the Spaghetti Western – Kurosawa Akira’s samurais were a big influence for Leone– Nic held nothing back. The movie is full of hilariously absurd dialogue and moments. It’s a territory that Sono dominates: just remember the hilarious yakuza leader secretly in love with the daughter of his rival, famous for a jingle that the criminal continues to dance, in Why Don’t You Play in Hell?

The plot of Prisoners of the Ghostland is quite simple: the Governor’s “granddaughter”, Bernice (Sofia Boutella), has disappeared; she’s actually a prostitute who managed to escape from her “prison.” The man with no name is imprisoned in Samurai Town and could regain his freedom if he fulfills the mission of bringing Bernice back.

The sequence that exposes the conflict is an extremely enjoyable display of the iconography around Cage’s character. The best example? The high-tech suit that threatens to blow the antihero to pieces if he treats Bernice badly (a comment from Sono about the supposed “misogyny” of his cinema?), or if he doesn’t fulfill the mission in the allotted time by the Governor.

Ok, maybe that doesn’t sound that crazy, how about adding a couple of explosives to the protagonist’s testicles? And we know that Sono wouldn’t add that detail if it wasn’t going to… explode at any moment!

Prisoners of the Ghostland is Sono’s Mad Maxian post-apocalyptic film. A world in ruins with old mannequins everywhere, a recurring figure in Sono’s filmography, as in Exte: Hair Extensions and in that twisted crime scene in Guilty of Romance. At the center of the stage is a crumbling tower topped by an immense clock, owned by a defunct nuclear empire.

After the Fukishima nuclear disaster in 2011, Sono hasn’t stopped showing concern about it in his cinema. There’s Himizu with its characters who lost everything and went on to live in destitute circumstances. In The Land of Hope, the director imagines that an earthquake and a tsunami cause a new nuclear catastrophe in another area of Japan. It’s a harsh criticism of the actions of the government and of the population with little memory, who forget the pain of ordinary people whose life will never be the same again.

In The Land of Hope, Sono thought of the threat of radiation as inherent in his country. Then, in Love & Peace, he used the frenzy for the imminent Tokyo 2020 Olympics (which haven’t happened yet, of course) as a reflection of a country that has forgotten Hiroshima, Nagasaki and Fukushima. Not for nothing the filmmaker continues to insist: the mythology of Prisoners of the Ghostland, explained in a stylized dreamlike sequence, is another comment on this topic.

Prisoners of the Ghostland is made up of a lot of elements. This post-apocalyptic world, and its background, is a hybrid. To avoid exploding into pieces, Cage’s character must enter a mythical land of ghosts, inhabited by figures distinguished by their distinctive samurai armor; they wander among men dressed in prison clothes, whose leader is a monstrous type, antagonist halfway between horror and exploitation.

The fate of those who cross the road of ghosts is the nuclear ruins. There’s no way out of this place, where an extravagant but well-meaning tribe lives. Some of these characters –like the charismatic Rat Man, a fanatic of vehicles and fuel-gatherer– might very well inhabit a fantastic adventure in a galaxy far, far away. In Prisoners of the Ghostland, Sono again turns his attention to the outcast; to children who have grown up without water or clean air, to ghosts that end up representing the aftermath of worldly horror, nuclear horror.

Prisoners of the Ghostland was filmed in Japan because Sono suffered a heart attack during its pre-production and, although the Japanese auteur doesn’t appear among the writers, the theme of reincarnation and redemption drives the film. Cage’s character is initially painted as a criminal of the worst kind, worthy of the Wild West of Corbucci. One of the ghosts that haunt him is an innocent Japanese boy, who had the misfortune of witnessing a disastrous bank robbery in which many of the characters and elements present in the story participated.

Prisoners of the Ghostland follows the man with no name until he earns the right to appear as a “hero” in the end credits. It’s an always insane absurdly entertaining redemption. Cage doesn’t stop, not even when he has to give the motivational speech as the “chosen one” that will make the impossible possible.

This is a quite violent film, although without reaching the most brutal, horrifying and controversial Sono of Cold Fish; there are stylized duels, sword thrusts, bullets and, of course, blood spurts. Prisoners of the Ghostland is absolutely bonkers and one of the most satisfying efforts by the great Sono Sion.

——————-

Watch Prisoners of the Ghostland on tubi here: https://tubitv.com/movies/100041245/prisoners-of-the-ghostland