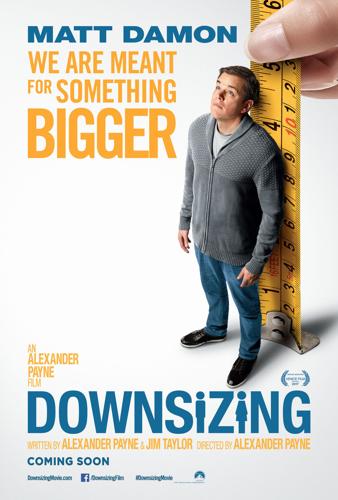

Let’s Get Small: Reckoning with “Downsizing”

“Look, you don’t understand. There was shrinkage!”

By Noah Gittell

Source: Good Eye

In his book Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs, essayist Chuck Klosterman wrote an essay defending the 2001 Cameron Crowe film Vanilla Sky from its reputation as a creative failure. Specifically, he honed in on critic Owen Gleiberman’s D+ review in Entertainment Weekly that accused the film of being little more than “a cracked hall of mirrors taped together by a What is reality? cryogenics plot.” Nonplussed, Klosterman pointed out that all the best films of this era—from The Matrix and Fight Club to eXistenZ and Mulholland Drive asked that same question about the nature of our reality. Klosterman argued that it was “the only relevant question for contemporary filmmakers.”

I bring this up to defend Downsizing, which is not a great film but deserves kudos for doing what Vanilla Sky did in the early ‘00s. Downsizing asks the only relevant question for filmmakers of its era: What should we do now that the world is ending? It asks this question all the way through, although its beginnings—the first third, basically—feels more like a broad comedy, which may have thrown some viewers. The film’s shifts in tone reminds me a bit of Zero Effect, one of my all-time favorites, which also presented itself as a wacky comedy before slowly transforming into something more profound. I have a theory that people—maybe critics in particular—don’t like movies that sell themselves as one thing and then become something else. It makes them feel manipulated or something.

I was up for it with Downsizing because if you look closely, it’s about the end of the world from the beginning. The film stars Matt Damon as Paul Safranek, an occupational therapist struggling to get his head above financial water. He and his wife (Kristen Wiig) accept a radical new solution: they will shrink themselves and head off to live in Leisureland, a community for the small where their scant savings will allow them to live like millionaires for the rest of their lives.

It turns out to be a real bait-and-switch, for Paul and for us. His wife leaves him just before the procedure, leaving Paul small and alone. After fighting depression for a year or so, he eventually gets caught up in the life of Ngoc Lan Tran (Hong Chau), a Vietnamese dissident who was a brief cause celebre after shrinking herself to escape political persecution and is now cleaning tiny houses for a living in Leisureland.

Despite the economic framing, Downsizing is pretty goofy up until this point, with a lot of sight gags built around objects that are not the size we’re used to seeing them. Still, there are hints of the thoughtfulness to come. The shrinking process is initially sold as a way to cut down on human consumption and save humanity from the ravages of climate change, but director Alexander Payne slips in some well-meaning commentary on how environmentalism is co-opted. Most people shrink themselves out of self-interest, using their duty to the planet as cover. When Paul reconnects with an old friend who has gotten small and asks him if it feels good to save the environment, the friend replies, “Downsizing is about saving yourself.”

It’s a neat summary of the problems of the film, which is ostensibly about saving the planet but is ultimately more committed to the journey of its average, White middle-class protagonist. When Paul meets Ngoc Lan, he discovers the dark underbelly of Leisureland: the projects on the wrong side of the tracks (okay, in this case, a tunnel), where she and an entire class of unseen, underrepresented workers live. Paul is horrified by their living conditions, and finds himself compelled to help her feed, bandage, and generally care for them out of the goodness of his heart. When he learns of an opportunity to visit the original small colony in Norway—and be included in their plan to start a new colony underground while waiting out the impacts of climate change—he must decide between being part of the privileged future or staying behind to help those afflicted in the present.

I’ve noticed that most people who have seen Downsizing seem to get fed up in this final third. Paul and Ngoc Lan travel to Norway with his debauched neighbors (a perfectly cast Christoph Waltz and Udo Kier), where the film completes its transition from broad comedy to meditation on the morality of Armageddon. Paul justifies his choice to be part of the future in selfish terms: ”Why didn’t I become a doctor? Why did I downsize? Why did my wife abandon me? So I could wind up here at exactly the time to go into that tunnel! I finally have the chance to do something that matters.” In the end—SPOILER ALERT—he stays on the surface, marries Ngoc Lan, and spends his downsized downtime helping the indigent.

I have no issue with the film’s transformation, and I admire its willingness to ask, as Klosterman puts it, the only relevant question of our time. It reminds me of the best moment in the political career of Andrew Yang, who, when asked at a Democratic presidential debate for his approach to climate change, gave a startlingly clear-eyed answer. Other candidates talked about the need to listen to climate scientists, transitioning to green energy, and, if they were feeling bold that day, a carbon tax. Yang looked right at the camera, and said something like (I’m paraphrasing), “I would allocate $40 billion to move every American family to high ground.” His honesty hit me like a load of bricks, and for a minute there, I thought we finally had a politician who would tell the truth. The bloom came off his rose pretty soon after that, but at least he didn’t deny reality, and neither does Downsizing. It should be commended for that.

It just chooses a poor lens through which to explore the issue. The film’s problems run along two intertwining tracks: creative and political. First, there’s something unseemly about Payne exploring these themes through a middle-class White protagonist. Watching Downsizing, you can’t help but wish Ngoc Lan were the main character, and Paul was just a sweet White guy she picked up along the way. Hong Chau gives a miraculous performance as the resolute activist. Yes, she uses a comically exaggerated Vietnamese accent that threatens to offend sensitive viewers, but her increasingly soulful performance overwhelms the stereotype. Was all this on purpose—the offense and the redemption? I tend to think so. Payne is telling this story for privileged White viewers, and he hopes that her transformation from, um, housecleaner into fully-formed human being will transform them into caring about those they would otherwise ignore.

Maybe it will, but I can’t help but feel he’d have a better shot at doing that if his main character weren’t the most boring person on the planet. I get the appeal of an Everyman in this type of story, but Paul Safranek does not need to be this bland. His backstory is compelling enough: He was going to be a doctor, but his mom got sick, so he moved back to his hometown to take care of her and became an occupational therapist instead. His mom died, and he married a seemingly sweet lady who inexplicably left him in the lurch. This series of events would produce an interesting person, or at least a recognizable personality, certainly more than the human blob that Payne, his co-writer Jim Taylor, and Matt Damon come up with here. On the page, Paul is torn between altruism and self-interest, but that conflict never comes to life on the screen. There’s no self-deprecation, black humor, frustration, or anger. It’s a bland performance by an actor who is capable of much more.

Downsizing still gets points for trying. Damon could have given a better performance, but the broader problem of centering a boring White man in this story was not really fixable. An FX-driven moral parable about the end of humanity would never be made without a movie star at its center, and certainly not for its reported $68 million budget—it’s kind of a miracle it got made even with one. And outside of Denzel Washington and Will Smith, there were no non-White movie stars at this time who guaranteed a certain box-office haul. Put simply, it always had to be Damon or someone like him, which means that Downsizing probably did the best it could under the circumstances. If you want to make a movie that reckons seriously with Armageddon, you’re gonna have to work with the devil to do it.

——————–

Watch Downsizing on Kanopy here:https://www.kanopy.com/en/kcls/video/13159250