By Charles Hugh Smith

Source: Of Two Minds

There are two approaches to analyzing a situation:

1. Choose the desired outcome–generally the one that doesn’t require any major changes, sacrifices or downward mobility

2. Identify the initial conditions and systemic dynamics and then follow these to a conclusion back-tested by comparisons with historical outcomes.

Our default setting as humans is 1: select the outcome we want and then find whatever bits and pieces supports that conclusion. Cherry-pick data, draw false analogies–the field is wide open.

This is why we get so upset when our “analysis” is challenged: we’re forced to ask what happens to us if our desired outcome doesn’t transpire, and since the answer might be something less than optimal, we violently reject any data or analogies that conflict with our carefully curated “analysis.”

A great deal of what passes for analysis today is cherry-picked bits and pieces that support a happy story of endlessly expanding prosperity–AI, fusion, etc.–with no mention of limits, constraints, costs or worst-case outcomes rather than best-case outcomes.

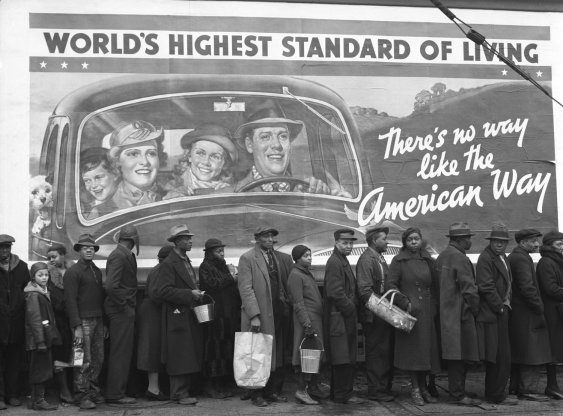

Let’s start with an historical analogy most reject: the Great Depression of 1929 to 1942. The conventional account claims that the Depression was the result of a “Federal Reserve policy error”: the Fed tightened credit when it should have loosened it.

This is nonsense. What actually happened was credit expanded rapidly in the Roaring 1920s, which is why they were Roaring. Farmers could borrow money to buy prairie land to put under the plow, speculators could borrow $9 on margin to play the stock market with $1 in cash, and so on.

In other words, what happened was a gigantic credit bubble inflated that pushed stocks and other assets to unsustainable heights of over-valuation, valuations based on the Roaring 20s expansion of credit and consumption continuing forever.

But all bubbles pop, and so the weather changed for the worse and newly plowed prairie turned into a Dust Bowl, wiping out heavily leveraged farmers. Since there was no federal bank deposit guarantee (no FDIC), the bankruptcies of overleveraged borrowers wiped out thousands of small banks, wiping out the savings of prudent depositors.

So even prudent savers got wiped out in the crash of the credit bubble.

Stock speculators gambling on margin (i.e. borrowed money) were quickly wiped out, and the selling became self-reinforcing, accelerating the cascading crash.

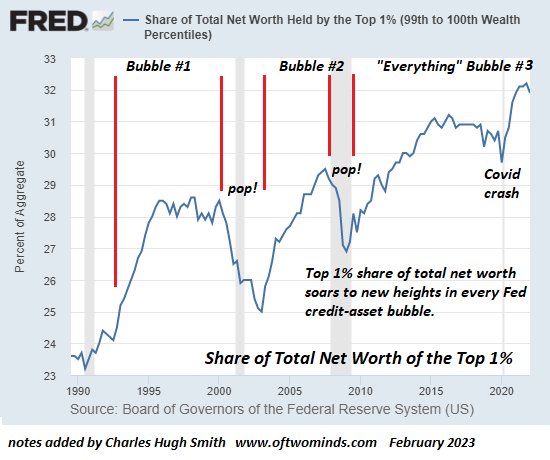

The real policy error was protecting the wealthy who owned the debt from a debt-clearing write-down. The wealthy own debt, the non-wealthy owe debt. When the debt is defaulted on, the lender / owner of the debt has to absorb the loss. The debtor is freed of the burden. In a debt-clearing event driven by defaults, insolvencies and bankruptcies, the wealthy are the losers and the debtors are freed of the burden of debt.

Various programs were implemented to stave off the consequences of default, as if pushing losses into the future would somehow enable the credit bubble to reinflate. That’s not how it works: the financial system is like a forest, and if the dead wood of bad debt piles up and isn’t allowed to burn, then the forest cannot foster new growth.

Economies that refuse to accept the wealth destruction that results from credit bubbles popping stagnate. This is the story of Japan from 1990 to the present: the status quo in Japan refused to accept the losses, hiding bad debt (i.e. non-performing loans) behind artifices such as new loans that covered the interest due, listing the non-performing loans in “zombie” categories, i.e. as assets that were still on the books at full value even though they were essentially worthless, and so on.

The net result was 33 years of stagnation and social decay as young people gave up on owning homes and having families.

Now the US has inflated another “debt super-cycle” credit bubble that has pushed assets into over-valuation. Once again the goal is to avoid handing the wealthy owners of all this debt the enormous losses that must be accepted to clear the dead wood of bad debt, money lent to borrowers and projects that were not creditworthy except in a bubble.

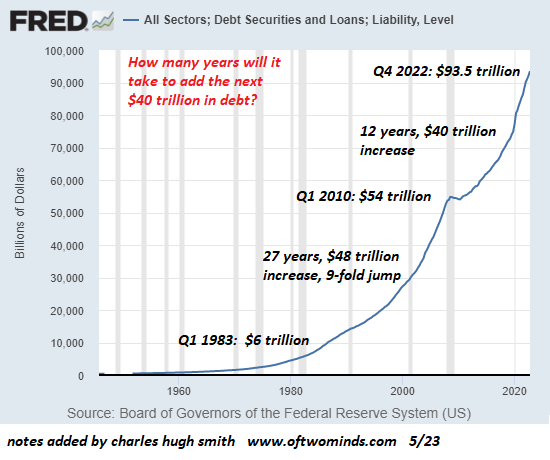

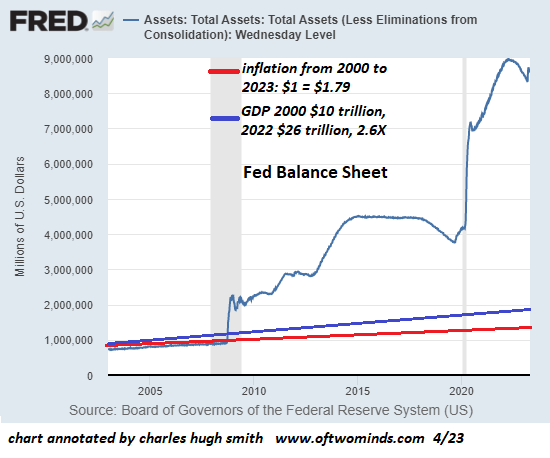

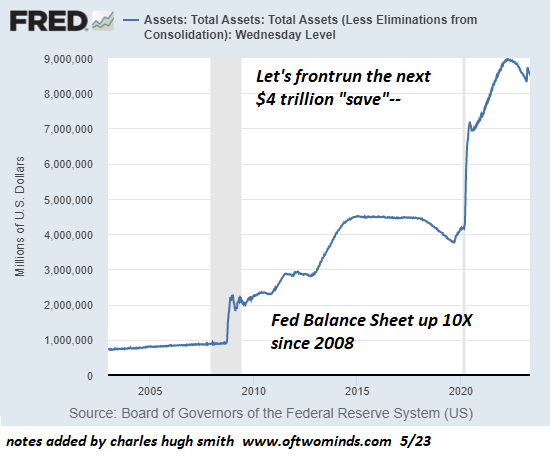

The lesson the status quo took from the Great Depression is to cover up private-sector over-valuations and bad debts with vast expansions of credit via the Federal Reserve and the federal government. Please look at these four charts below:

1. total credit (TCMDO)

2. the Federal Reserve balance sheet (2 charts)

3. federal debt

All are in visibly unsustainable parabolic ascents.

Predictably, the status quo will refuse to accept the necessity of clearing the dead wood and accepting the trillions of dollars in losses that will accrue to those who own the unpayable debts.

Consider CRE, commercial real estate. Office towers are now worth one-third of their pre-pandemic valuations, the valuations on which their mortgages were based. There is no way these properties can be magically restored to their previous over-valuation. Massive losses must be accepted by the owners of the debt. If those losses make them insolvent, so be it. That is unacceptable in a system geared to protect the wealthy at all costs.

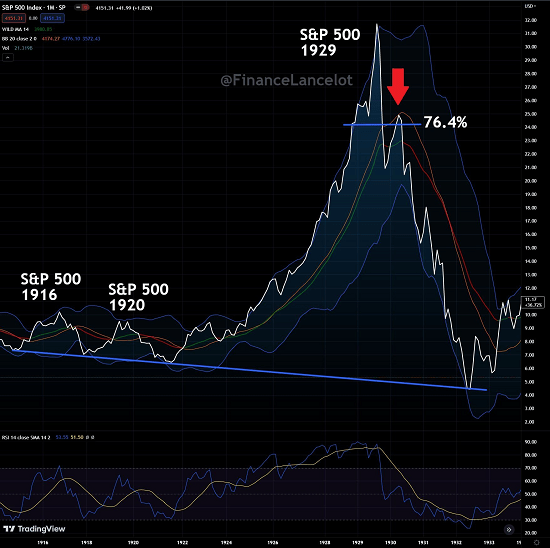

But bubbles pop anyway, regardless of policy tweaks. Consider these stock market charts of the Roaring 20s and the Great Depression and the present (below). The similarity is remarkable–possibly even eerie.

The big difference between the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Depression we’re entering is the world still had enormous reserves of resources to tap and a (by today’s standards) modest population in the resource-consuming developed nations.

Recall that a developed-world consumer uses up to 100 times more energy and resources than a poor person in a rural undeveloped nation. Recycling a few bottles doesn’t change this.

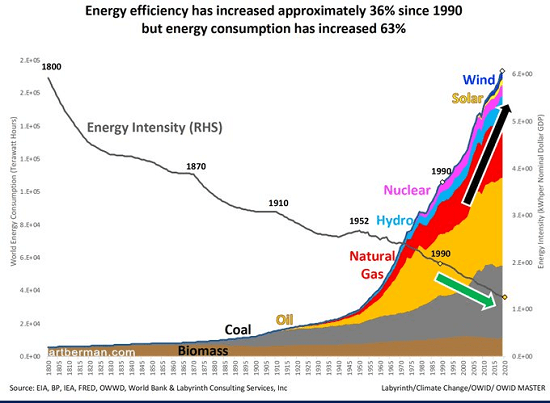

This means the planet’s “savings account” of abundant, cheap-to-access resources has been depleted. Yes, there is still oil and copper, etc., but it’s of far lower quality and much harder to get now. The rich ores have been mined and the shallow super-giant oil fields have all been tapped long ago. Now the Saudis must pump stupendous quantities of seawater into their oil wells to maintain production. All these technologies consume vast quantities of energy.

The inevitable result is the energy efficiency–how much energy is required to access, process and transport the energy–has plummeted even as consumption has soared.

The outcome many hope for is some new miraculously cheap and abundant sources of energy such as fusion. But fusion is far more complicated and tricky than pumping oil, and oil is a high-energy-density fuel that can be stored rather easily. All the electricity generated by various technologies can’t be stored easily or cheaply, and so the happy story is that a new miraculous battery technology is just around the corner.

But batteries are also complicated and resource-dense, so they’ll always be as expensive as the materials needed to fabricate them. There will never be “low-cost” batteries if the materials needed to make them are scarce and expensive to dig out of the ground, process and transport.

So the policy choices are simple: either protect the wealthy from write-downs of bad debt and the collapse of asset bubbles and usher in decades of stagnation, or force the wealthy to take the losses and clear away the dead wood.

But either choice will be constrained by the reality that humanity has already drained the easy-to-get “savings account” of global resources.

I get emails from readers who say things like “mining techniques are far more efficient now.” That’s fine, but most of these new mines are often thousands of kilometers away from railways or seaports, and thousands of kilometers away from the processing plants that turn the ore into useful metals.

Recall the enormity of the cost and effort required to build a single two-lane highway thousands of kilometers to a new mine, and the oceans of diesel fuel needed to power the mining equipment and trucks hauling the ore to railways or seaports. Recall the immense amounts of energy required to smelt / process these ores, and the near-zero percentage of lithium-ion batteries that are currently being recycled.

Batteries are difficult to recycle because they’re not manufactured to be recycled, and they’re not manufactured to be recycled because that would raise costs considerably, reducing profits.

So on the present course, the idea is to manufacture billions of batteries, throw them all in the landfill in 10 years, and then mine enough minerals to build another couple billion batteries and then repeat the cycle of throwing them away in 10 years forever.

That isn’t realistic, so the status quo will have to adjust to this unwelcome reality.

This is why I keep writing books about relocalizing, degrowth, using less rather than more to yield a higher level of well-being. The resource “savings account” won’t support fantasies of endlessly expanding consumption of hard-to-get resources.

But the status quo has much to unlearn, and it seems the only pathway to a new understanding is a Great Depression that won’t end with a new expansion of credit because the resources required for that new expansion simply won’t be available or affordable.

Reducing our exposure to avoidable risks is a key strategy of Self-Reliance.