By Seth Harris

Source: Pop Cult

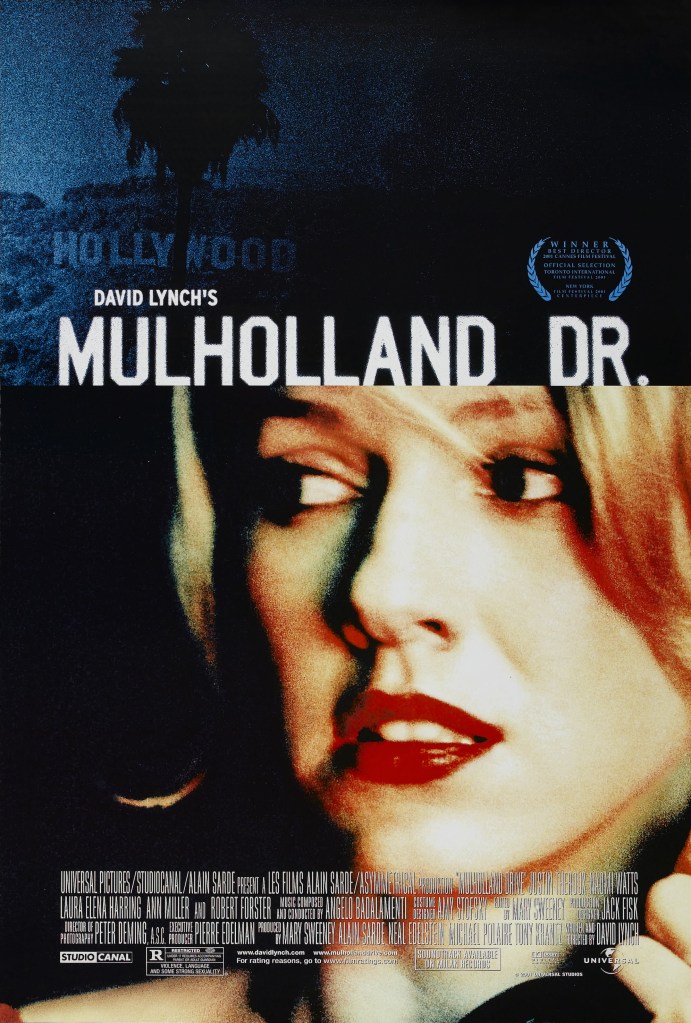

I’ve mentioned on the blog before how I discovered David Lynch as an eight-year-old who was somehow allowed to watch Twin Peaks. For a long time, I knew him as “the guy who made Twin Peaks.” Even in college, as I began to explore his greater body of work, I was like most people; I just didn’t understand the abstractness of it all. What shifted my understanding was reading Lynch on Lynch, a book of interviews with the director focusing on his work in chronological order up to Mulholland Drive. Through this text, I came to understand the source of Lynch’s creativity – from deep inside his subconscious and expressed through images without any implied context – and how intuitive his work is. This happened around the same time I was taking Literary Theory & Criticism, which was probably the most influential academic experience I’ve ever had.

Mulholland Drive begins with a woman (Laura Harring) being driven to a party on the titular road. However, she was never going to arrive at the party. Her driver turns on her, and before they can assassinate the woman, the limousine is hit by a car of rowdy young people. The woman stumbles down a hillside and eventually hides in an apartment whose owner has a department for a long trip. This is the home of Betty’s (Naomi Watts) aunt, where the young woman has come to stay while she auditions in the hopes of becoming a movie star. She immediately feels empathy for the amnesiac woman and vows to help her. Her unexpected guest takes the name Rita after seeing a movie poster of Rita Hayworth in the apartment.

The two women begin investigating the few threads they have about Rita’s past. Meanwhile, a film production grinds to a halt as its lead actress has been let go. The director, Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux), is put through the gauntlet, having the worst day of his life as recasting her, and is placed in the hands of more powerful people. He arrives home to find his wife cheating on him with the pool boy. And then, while bedding down at a flea-bitten motel, Adam discovers his assets have been frozen. How does this relate to Betty and Rita? Well, they weave in and out of his story along with other elements that seem detached. By the end, the truth comes out in a strange place called Club Silencio, which holds the key to understanding it all.

I am going to talk about Mulholland Drive in more depth now, so if you haven’t seen the film I wouldn’t recommend reading any further.

The story of Betty & Rita is a dream. Lynch often has his character’s waking mind and dreaming subconscious collide, and it is very literal here. Betty is, in reality, Diane, a waitress at a coffee shop with aspirations of being an actress. She even has a small part in a production, which is where she met Camilla. Camilla is bisexual and did enjoy her time with Diane. However, the director of the picture, Adam, has taken a liking to his star. She’s more than happy to go along with it, but that leaves Diane reeling as she comes to understand her love was not reciprocated.

A plan is hatched. Diane pays a guy she knows to have Camilla killed, but the guilt of what she has done causes Diane’s mind to splinter. A dream forms, which is where the film begins, and it sees Camilla escaping her fate. And who does her hero end up being? Well, it’s Diane’s dream self of Betty. Diane imagines herself as far more innocent, caring, and talented than in real life. She also imagines that Camilla, as Rita, is wholly dependent on her. In her dream, Adam gets sent through the wringer, too. But the truth begins seeping in, little details here and there. It culminates at Club Silencio, where Diane’s conscious mind reminds her that what is playing out before her eyes is an illusion. This, in turn, forces her to wake up, and we finally see the horrifying truth of Diane’s life.

Lynch delivers a noir film that captures every element you would expect from such a story while still feeling wholly original and fitting into his body of work. It has the dream logic of a Lynch film, yet it is his most accessible picture. The pieces are all there on screen; he’s just not going to spoon-feed you. To engage with the work, consider what is said and the connections between images. Remember, Lynch is first a visual artist before a storyteller, so you can understand what is happening. This was the film that brought Roger Ebert around to finally appreciating Lynch after two decades of turning his nose up at the work.

But even more significant than Diane’s story is a reflection by Lynch on the nature of Hollywood as an American institution. He is an artist who didn’t start out interested in making movies. He wanted to paint. His experience on Eraserhead caused him to both love making movies and hate them at the same time. It would be Dune that helped calcify the idea of making the films he wanted to make without interest in whether they were going to be financially successful for his backers. He’s never made a movie he didn’t want to since then.

Twin Peaks is what made him famous on a whole other level, and once again, he was forced to walk amongst the Hollywood machine again. It should be noted that Mulholland Drive originated as a TV series about Audrey Horne going off to become a movie star and getting embroiled in noir storylines. It seems evident that this idea centered around how young women are especially forced to compromise and do things that give up their power to a man to make it. This makes sense and continues Lynch’s exploration of the abuse of women in the United States, which is the thematic centerpiece of Twin Peaks. He’s not a direct storyteller, so you’re expected to find these ideas; he trusts your intelligence to do that.

Club Silencio is a comment not just on Diane’s dream over her actions but on the dreams of so many to come to Hollywood and be “discovered.” Years ago, I read Hollywood Babylon, a collection of sordid industry gossip by former child star Kenneth Anger. It was quite a harrowing read. Things like the Fatty Arbuckle trial are relatively well-known, but there was so much more. There are hundreds of people you’ll probably never hear about who were murdered or committed murder or helped cover it up within the film industry. It didn’t necessarily involve big stars but people who worked in various capacities. There was a lot of money changing hands, and people were desperate to escape poverty. These circumstances often cause people to do terrible things.

Lynch’s work always seems focused on dismantling mythologies. Blue Velvet was about the myth of the friendly, quiet small town. Twin Peaks continued that but focused even more on the myth of the happy nuclear family with a mountain of abuse hidden just beneath the surface. It makes sense because the director is fascinated with the subconscious mind. He is a big proponent of transcendental meditation, which is all about engaging with those layers of our consciousness that we mostly avoid or ignore. Lynch doesn’t see dreams as a well of chaos but as a place where profound coherence can be discovered. The language of dreams is not the same as the waking world and it is in our inability to translate that our problems arise.

It should also be pointed out that Mulholland Drive’s construction acts as a Mobius strip. There is no beginning or end, just one continuous loop. Betty and Rita find Diane’s body rotting away in her apartment in the dream. The old couple that terrorizes Diane is the same couple that ushers Betty into the fantasy version of Hollywood. They have brought her there. What we are experiencing is a sort of Hell where Betty/Diane is forced to relive the torment of delusion & revelation over and over and over and over… In this way, I consider it one of Lynch’s most horrific films.

Watch Mulholland Drive on tubi here: https://tubitv.com/movies/385509/mulholland-drive