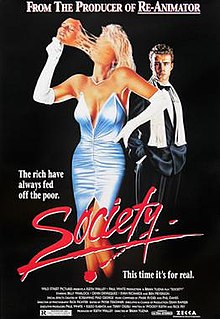

“A Matter of Good Breeding”: The Shape-Shifting Elite in Brian Yuzna’s ‘Society’

By Noah Berlatsky

Source: We Are the Mutants

The elite is an amorphous clotted blob of parasitic greed and hate. Its tendrils extend with slimy stealth into every orifice of society—which makes its precise outlines difficult to see. Are the elite contemptuous coastal liberals and academics? Are they hedge fund managers and tech billionaires? Are they infiltrating globalists or capitalist pigs? Are they your bosses? Or are they your neighbors sneering at your MCU films and your fast food diet? Or are they all of these people and more, gelatinously fusing into a suffocating, boundaryless mass, conspiring in the dank corners of the hierarchy to feed upon and absorb your labor and your soul?

Brian Yuzna’s 1989 schlock horror film Society slides its moist appendages around the concept of the elite, queasily exposing its power and its vile plasticity. Squeezing into the paranoid horror genre at the very end of the Cold War, Society contorts itself away from the communist menace to focus on the evil assimilating rituals of a boneless capitalism. In doing so, though, it inadvertently shows how difficult it is, with the tropes of terror we have, to tell communism and capitalism apart. The two dissolve into a single two-headed, or multi-headed, or faceless mass, impossible to pin down or define, and therefore impossible to escape.

Society‘s protagonist is Bill Whitney (Billy Warlock), a wealthy Beverly Hills teen and star basketball player running for student body president. Everything seems to be going well for him. And yet, “If I scratch the surface, there’ll be something terrible underneath,” he tells his therapist, Dr. Cleveland (Ben Slack), just before biting into an apple and seeing it squirming with (hallucinatory?) maggots. The worm in Bill’s Garden of Eden is his family. His parents Nan (Connie Danese) and Jim (Charles Lucia) are much closer to his sister Jenny (Patrice Jennings) than they are to him. He suspects they don’t love him; he worries he is adopted. Soon, though, he has cause for even more serious alarm. His sister’s ex-boyfriend David Blanchard (Tim Bartell) secretly bugs Bill’s parents and sister; on the tape the three of them reveal that Jenny’s debutante coming out party is a bizarre incestuous group sex ritual. When Bill tries to share the evidence, the tape disappears, and Blanchard is killed in a car crash. The wooden acting and incoherent plot tremble between B-movie incompetence and sweat-drenched fever dream as the conspiracy begins to engulf everyone from Bill’s rival, Ted Ferguson (Ben Meyerson), to his new girlfriend Clarissa Carlyn (Devin DeVasquez), to his doctor, his parents, and the police.

In the film’s infamous conclusion, we learn that Bill was in fact adopted, and his parents and their friends are part of a shape-shifting species that devours humans in a bizarre group feeding sex ritual called the “shunt.” The last twenty minutes of the runtime are an oozy apocalypse courtesy of special effects guru Screaming Mad George: flesh dissolves, mouths turn into clotted rubbery tendrils, and Bill literally reaches up through Ted Ferguson’s anus to pull him inside out in a climactic battle, ending Ted’s life and Bill’s hopes of a Washington internship. Clarissa is so in love with Bill that she betrays her own species, and she, Bill, and Bill’s buddy Milo (Evan Richards) escape the clutches of the elite, whose members have to satisfy themselves with eating Blanchard, saved from his apparent death by car crash for an even more awful fate.

Society is a decadent, absurdly sodden and febrile extension of the body horror genre of the ‘70s and ‘80s, taking The Thing (1982), 1985’s Re-Animator (which Yuzna produced), The Blob (1988), and The Fly (1986), and adding even more K-Y Jelly and quivering sexual innuendo. It can also be seen, though, as a reversal of those late Cold War-era films, reaching through the back end to grab hold of the eye sockets from the inside to pull out the wet, pulsing innards. Just as the Berlin Wall was falling, Society revealed that the fear of the Soviets was fear of the wealthy elite all along.

***

Anti-communist paranoia in Cold War horror often centers on deindividuation and dehumanization. Ronald Reagan was channeling films like 1954’s Them!, with its giant, mindless insect invaders, when he described Communism as an “ant heap of totalitarianism.” The 1958 The Blob features a figurative Red menace: a clump of gelatin fallen from space that absorbs all those in its path, dissolving discrete persons into a single jelly-like mass. 1956’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers imagines alien seed pods falling to earth, from which gestate repulsively fibrous duplicates. They drain human appearance and personality when, in a metaphorical excess of failed vigilance, their targets fall asleep. “Love, desire, ambition, faith—without them life’s so simple,” a pod person explains to the horrified protagonists, sketching a vision of a world enervated by a lack of human warmth and capitalist moxy. Significantly, one of the first signs of the pod invasion is a dual leeching away of business initiative and consumerist impulses. Dr. Miles Binnell (Kevin McCarthy) first notices something awry when he sees an abandoned roadside vegetable stand. Later, when he takes Becky Driscoll (Dana Wynter) out to dinner, the restaurant is almost abandoned. Pod people neither sell nor buy; the hive mind, possessed of invisible tendrils, does not require an invisible hand.

Communism doesn’t just eat through commercial relationships in these films; it eats through domestic ones. Removing consumer desire also removes traditional sexual and romantic impulses, leaving behind monstrous abomination. Science-fiction author Jack L. Chalker neatly summarizes the anti-communist logic in his 1978 novel Exiles at the Well of Souls, in which humans have created Comworlds where “The individual meant nothing; humanity was a collective concept.” To advance that group good, the Comworlds retool sexual biology itself: “Some bred all-females, some retained two sexes, and some, like New Harmony, bred everyone as a bisexual. A couple had dispensed with all sexual characteristics entirely, depending on cloning.” In one of the most quietly ugly moments in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, a working mother prepares a pod for her own baby, noting in a monotone that soon it won’t cry. Plants replace wombs just as outsourced childcare replaces homemaking, and maternal feelings dissolve into a grey, ichorous, proto-feminist puddle.

The 1970s remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers further teases out the bleakly kinky implications of mind-controlled interference in the reproductive process. Elizabeth Driscoll (Brooke Adams) falls asleep in a field, and, as her personality is sucked from her, her body cracks and crumbles like a rotten pumpkin. Nearby, she rises up in her new form, “born again into an untroubled world, free of anxiety, fear, hate”—and also free of clothes. Pod Elizabeth is completely nude, and the film’s stark gaze willfully conflates desire and terror. In fact, the terror is precisely that she is both fully available and completely unavailable, a desirable body in thrall to some inhuman mass will.

Society takes that body and molds it to different ends. The communist infiltration is replaced with a festering class divide. Good, upstanding businessmen, mothers, and citizens are not infected with an alien ideology. Instead, as the maniacal Dr. Cleveland explains, “No, we’re not from outer space or anything like that. We have been here as long as you have. It’s a matter of good breeding, really.” The parasitic infection is not foreign, but native. No one has been changed; rather, the paranoid revelation is that the evil ones were here all along, squatting wetly in those mansions, and sliding hideously into prestigious internships. No blob or pod or thing needs to take control of the judges, the police, the hospitals, and the student presidency. The blob/pod/thing is already here, salivating. “Didn’t you know, Billy boy, the rich have always sucked off low-class shit like you,” Ted Ferguson sneers, before rolling out an impossibly long tongue to sloppily lick his prey.

Ted’s tongue slides around various kinds of appetite; the rich are hungry not just for deviant power, but for deviant erotics. Just as communism in horror films disorders sexuality, so in Society the rich are marked as evil in large part because of their hypocritical flouting of family values. “We’re just one big happy family except for a little incest and psychosis,” Bill tells Dr. Cleveland nervously, and it’s truer than he knows. His parents and sister share improbably pliable group sex. In a polymorphously perverse primal scene, Bill walks in on them, discovering his mother lying back with her legs turned into arms, and sister Jenny’s head sprouting from her genitals. “If you have any Oedipal fantasies you’d like to indulge in, Billy, now’s the time,” Jenny shrieks gleefully—vapid ‘80s high-class party teen revealed as demonic sexual reprobate.

Billy does have uncomfortable fantasies. Earlier in the film, before he knows what he’s dealing with, he walks in on Jenny in the shower. What he sees is one of the strangest erotic images in film history: through the glazed glass, his sister is facing him from the waist up, her breasts clearly visible. But below the waist her butt is towards him. Bill is frozen in confusion and desire at the sexual grotesque, a literally twisted incestuous spectacle. This erotic narrative stasis is something of a motif in the film. The plot slows down to catch Bill’s wide-eyed reaction during the student president debate, when Clarissa in the audience opens her legs, foreshadowing Sharon Stone’s more explicit move in Basic Instinct (1992) a few years later. Bill similarly comes to a staring halt while watching his parents inspect a phallic, writhing slug in the garden—and then again on the beach, when he is crawling to try to recover some fallen suntan lotion stolen by a couple of mischievous kids. Clarissa, entering stage right, picks up the lotion, and, leaning over him, sprays his face, a move that mimes ejaculation in a phallic role reversal. Finally, when Bill actually has sex with Clarissa, the expression on his face is one of distress and horror as much as pleasure—perhaps because at the height of passion, her left hand slides down sensuously over her back and then down her right arm, as if it’s been cut loose from her body and has wandered off on its own.

The movie itself mirrors Bill’s conflicted gaze, simultaneously fascinated and sickened. The climax is a special effects money shot in multiple respects. The scene is exuberantly concupiscent, with group sex, incest, porn movie tongue kisses, and indeterminate bodily fluids all slickly fusing. The leader of the shunt, Judge Carter (David Wiley), mutters greedily about Blanchard’s beauty mark before devouring him with his mouth, and shoving his hand up his anus. Homosexuality is framed as the ultimate decadence—a terrifying embodiment of penetrative lust that makes you recoil, laugh, and feel things you don’t, or do, want to feel.

The shunt is the Communist blob, with joy added. Judge Carter, Ted, and Jenny all obviously love the shunt. “It’s so fun to see how far you can stretch,” one of Jenny’s fellow shunters tells her. “The hotter and wetter you get the more you can do. It’s great!” The wealthy elite should be opposed to the depersonalization of Communism, but instead they leap in, eager and willing. They’re the enthusiastic audience for all those Cold War films, cheering for the goopy appearance of the Blob.

If all those capitalist viewers loved consuming the Blob, was the Blob ever really a Red Menace in the first place? The problem with seeing Society as an inversion of Cold War anti-communist narratives is that those Cold War anti-communist narratives were often torso-twisted replicas of themselves anyway. The 1988 Blob, for example, replaces the invading goop from space with a biological weapon created by the U.S. government; the shapeless metaphor for communist invasion heaves and bulges and becomes a shapeless metaphor for capitalist invasion.

John Rieder, in 2017’s Science-Fiction and the Mass Culture Genre System, points out that the anti-communism of Invasion of the Body Snatchers can also be read as a terror of capitalism, alluding to the economic signifiers I mentioned earlier.

One of the first signs of the invasion is the closure of a small farmer’s produce stand. Later we see a restaurant losing its business. Finally a group of aliens conspires behind a Main Street-type storefront after one of them grimly turns the sign on the door from Open to Closed. What these emptying-out and closures signify is an economy bent entirely on the production and distribution of seed pods. The colonizing economy is not attuned to the local needs that a produce stand responds to, but rather focuses solely on the single-minded propagation and export of its one and only crop.

The machinations of the body-snatching elites hollow out the town of Santa Mira, just as the society feeds on Blanchard—or just as the vampire feeds in 1922’s Nosferatu. Bram Stoker’s decadent, parasitic aristocrat was robbing helpless victims of their will and individuality via debased, incestuous, homoerotic sexual rituals long before the Cold War seedpods split open. Anti-communism spawned anti-elitism, and anti-elitism spawned anti-communism. Rieder argues that the real danger of the pods is “monopolistic corporate capitalism,” not communism. But which take is the true reading is less important than the way anti-communism is an indistinguishably parasitic replication of anti-capitalism, and vice versa. The tropes of anti-elitism and of anti-communism are grown from one bloated pod. Both dissolve personality, virtue, ambition, love, and sex into a repulsive muck that lives only to eat and perversely reproduce.

Perhaps the best example of how radical and reactionary horror tropes sprout from one another is John Carpenter’s 1988 classic They Live. In the movie, John Nada (Roddy Piper), a virtuous, optimistic, working-class protagonist, discovers that cadaverous aliens are living among us, controlling us with television messages that turn us into obedient, consuming drones. The movie is widely considered a critique of Reagan-era neoliberalism, and it is that. But it’s also a story about the virtues of genocide. A white guy discovers aliens who don’t look like him living in his town, and his first impulse is to murder them. Foreign shape-shifting immigrants, like vampires, are a standard anti-Semitic stand-in for Jews, and They Live can be read as a fascist conspiracy theory, in which brave working Americans finally recognize their racial oppressors, and respond with righteous cleansing violence.

Actual neo-Nazis have in fact read the film in exactly this way. Director John Carpenter insists that this was not his intention, and there’s no reason to disbelieve him. But tropes, like pod people, have minds of their own. When a creator assembles signs that signal “anti-elitism,” those same signs exude a duplicate, indistinguishable signal that is “anti-communism” or its frequent partner on the right, “fascism.” This is certainly the case in Society, a film in which Judaism is as slippery as sexuality. David Blanchard, we’re repeatedly told, is not the right kind of boy to date Jenny. That’s in part, we learn, because he’s Jewish. After his car accident, he has an open casket funeral in a synagogue. The problem is that Jewish people don’t have open casket funerals. Blanchard, whose corpse is faked by the society, is, it turns out (and unbeknownst to the film creators), a fake simulacra of a Jew.

If Blanchard isn’t really a Jew, it follows that the group that rejects him is made up of fake gentiles. And indeed, the vampiric, endogamous, shape-shifting vampires of the society are a not-very-buried anti-Semitic caricature. “You’re a different race from us, a different species, a different class. You’re not one of us. You have to be born into society,” the creatures tell him. This is a statement about the insularity, privilege, and snobbishness of the hereditary rich. But it’s also a racialization of class that is uncomfortably congruent with anti-Semitism. When the rich are horned devils feeding on the blood of your progeny, that could mean they’re not the rich at all, but the usual scapegoat.

Society expresses its disgust for the elite through the visceral, loathsome, oily imagery of homophobia, anti-Semitism, and anti-leftism. Class critique in the popular imagination draws parasitically on the stigmatization of marginalized people, and on tropes of deindividuation and sexual disorder sucked up from anticommunism. This is in part why it’s been so easy for the right over the last half century and more to position itself as the defender of working people. We have built the rhetoric of anti-elitism and the rhetoric of fascism from the same putrid, writhing flesh. If we don’t find a better way to imagine resistance, and soon, society will consume us too.

Watch the full film on Kanopy here.