By Daniel S. Levine

Source: Move Mania Madness

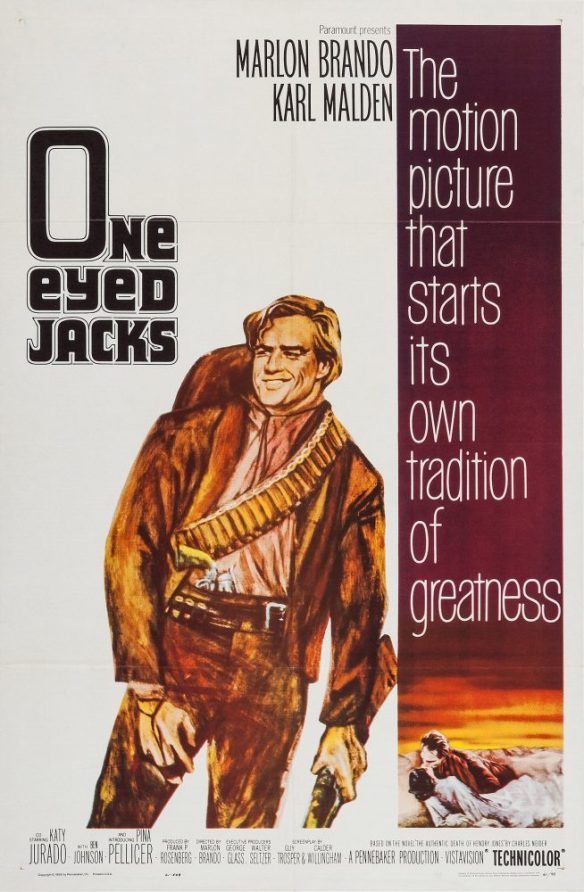

“You may be a one-eyed jack around here, but I’ve seen the other side of your face.”

Marlon Brando’s One-Eyed Jacks (1961), the only film America’s greatest screen actor ever directed, was itself a one-eyed jack for many years. Seen as an example of excess and the dangers of handing a star with a big ego a big budget, we are now seeing the other side of its face. Thanks to the incredible restoration by Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation, the film has been saved and we can now see the true wonders hidden by One-Eyed Jacks‘ production issues and public domain status.

Brando stars as Rio “The Kid” and Karl Malden (Brando’s co-star in On The Waterfront and A Streetcar Named Desire) plays “Dad” Longworth. At the start of the film, Rio and Dad pull off a heist in a Mexico town. During the chase, they split up, with Rio left to fight the Mexican authorities himself and Dad going to get new horses. But instead of returning to help Rio, Dad decides to escape. Rio is caught and jailed.

Five years later, we suddenly see Rio escaping prison with his friend Chico (Larry Duran). He picks up Bob Amory (Ben Johnson) and Harvey Johnson (Sam Gilman) while on the trail to find Dad. That trail leads him to Monterey, California, where Dad is now the sheriff. What follows is nearly two hours of pure tension, watching the blood boil between the two as Dad and Rio move their chess pieces ever closer to a final duel that’s over in a flash. Each action the two men take – from Rio romancing Dad’s step-daughter Louisa (Pina Pellicer) to Dad framing Rio for a bank robbery and murder – is meant to move them closer to a crescendo.

One-Eyed Jacks is hardly perfect and one does wonder what a seasoned director like Stanley Kubrick (who was signed on to make the film at first) would have done with it. But it is doubtful anyone but an actor-as-director could have brought out vibrant performances as Brando did. We can see what the characters are thinking, something few movies can achieve without voiceovers. He has full faith in the audience to figure out what’s going on without dialogue, but he also doesn’t go for heavy-handed symbolism. Yes, there’s that beautiful shot of waves crashing behind Brando, but much of the film plays out in the characters’ minds when their words fail them.

It’s hard to see how Westerns after One-Eyed Jacks could exist without it, especially Sergio Leone’s films. If anyone was listening to Brando in 1960, One-Eyed Jacks would have announced the death knell of the Classic American Western long before Sam Peckinpah shot it to hell with The Wild Bunch. Although Peckinpah’s work on One-Eyed Jacks was likely completely gone by the time filming began, there still seems to be a bit of Peckinpah DNA left in the final result.

Based on the novel The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones by Charles Neider, the plot echos themes and plot points that later show up in the “revisionist” Westerns of the late 1960s and ’70s. We have two men scarred by a betrayal, a hero on the wrong side of the law and a corrupt official. Sadistic men roam this world, others are guilty until proven innocent and townspeople are mere casualties in their play.

There are truly few other movies like One-Eyed Jacks, a film that simultaneously breaks from Hollywood tradition while following it. The additions Paramount insisted Brando make don’t completely strip away his vision for a movie. It might not have been a success at the time, but the rebellion against the old system it declared certainly was.

By Sheila O’Malley

Source: RogerEbert.com

Keanu Reeves has a mixture of stilted awkwardness and gangly grace that is uniquely his own, and that makes him an often strange, disaffected presence. This can either work or not work. His line readings are sometimes baffling. But his simple sense of truth and touching trust in the material (whatever it may be) is one of the reasons his career has lasted so long. There isn’t a ton of ego in his work. It’s refreshing.

“Man of Tai Chi”, Reeves’ feature film directorial debut, has the same sometimes-awkward blend that Reeves brings to the table as an actor. The film is super serious (as befitting the martial arts genre, where everything is a matter of life or death), with moments of strange stilted dialogue (also par for the course) and scene after scene of thrilling physical combat, filmed with grace and certainty and no small amount of awe for the athletes involved.

Tiger Chen, a stuntman in the two “Matrix” sequels, plays the eponymous character, also named “Tiger Chen”. He is a devoted practitioner of the ancient art of tai chi, working with a master named Yang (Yu Hai) in a beautiful temple. For his day job, Tiger works as a delivery boy, driving packages around the city, and flirting with a receptionist at one of his regular stop-offs. He lives with his parents. He does not have ambition to “do anything” with tai chi, because the rules underlying his apprenticeship with Master Yang say that those who practice tai chi do not do so for money, glory, or even to win. But during a public competition, his undeniable skill brings him to the attention of a mysterious individual named Donaka Mark (Reeves). Donaka lives in a cold man-cave of a penthouse, furnished in black leather and chrome. He strolls around barefoot on shiny black marble floors, he speaks only in terse commands. He has a security detail working for him that would rival the NSA’s. He reaches out to Tiger, offering him a security job, when in reality it is a recruitment for a deadly underground fighting ring.Tiger is flown to an undisclosed location, put into an empty grey room with a mirror on one wall, as he waits to see what will happen. A female voice commands: “Fight”, and from out of nowhere an opponent grabs Tiger from behind. Tiger is then engaged in a fight for his life in that grey room with the big mirror, and it is an Alice-through-the-looking-glass moment which will bear fruit through the rest of the film: Like Alice, Tiger is catapulted from one strange experience to the next. The normal rules of regular life no longer apply.

Donaka, of course, is watching through that mirror. That first fight is a test. Tiger passes, but it is only the first of many. Donaka’s fight club is run like a cult, where essential information about the nature of the organization is withheld from the participants until they are too deeply embroiled to get out. Tiger finds himself back in that grey room again and again, fighting increasingly vicious and skilled opponents. To what purpose? What is it all for?

The money Donaka offers is substantial. When Master Yang’s temple is slated for demolition unless money can be raised for necessary repairs, Tiger caves. And so the sacred temple is now being financed by someone who has betrayed the underlying principles taught there, a terrible irony. Tiger Chen, a superb athlete (to watch him is to go slack-jawed in wonder and appreciation), is also a terrific actor, going believably from sweet open kid to cold lean killer with a haunted aspect. “Man of Tai Chi” takes place in a deeply moral universe where our choices have spiritual implications.

Tiger Chen, a stuntman in the two “Matrix” sequels, plays the eponymous character, also named “Tiger Chen”. He is a devoted practitioner of the ancient art of tai chi, working with a master named Yang (Yu Hai) in a beautiful temple. For his day job, Tiger works as a delivery boy, driving packages around the city, and flirting with a receptionist at one of his regular stop-offs. He lives with his parents. He does not have ambition to “do anything” with tai chi, because the rules underlying his apprenticeship with Master Yang say that those who practice tai chi do not do so for money, glory, or even to win. But during a public competition, his undeniable skill brings him to the attention of a mysterious individual named Donaka Mark (Reeves). Donaka lives in a cold man-cave of a penthouse, furnished in black leather and chrome. He strolls around barefoot on shiny black marble floors, he speaks only in terse commands. He has a security detail working for him that would rival the NSA’s. He reaches out to Tiger, offering him a security job, when in reality it is a recruitment for a deadly underground fighting ring.Tiger is flown to an undisclosed location, put into an empty grey room with a mirror on one wall, as he waits to see what will happen. A female voice commands: “Fight”, and from out of nowhere an opponent grabs Tiger from behind. Tiger is then engaged in a fight for his life in that grey room with the big mirror, and it is an Alice-through-the-looking-glass moment which will bear fruit through the rest of the film: Like Alice, Tiger is catapulted from one strange experience to the next. The normal rules of regular life no longer apply.Donaka, of course, is watching through that mirror. That first fight is a test. Tiger passes, but it is only the first of many. Donaka’s fight club is run like a cult, where essential information about the nature of the organization is withheld from the participants until they are too deeply embroiled to get out. Tiger finds himself back in that grey room again and again, fighting increasingly vicious and skilled opponents. To what purpose? What is it all for?

The money Donaka offers is substantial. When Master Yang’s temple is slated for demolition unless money can be raised for necessary repairs, Tiger caves. And so the sacred temple is now being financed by someone who has betrayed the underlying principles taught there, a terrible irony. Tiger Chen, a superb athlete (to watch him is to go slack-jawed in wonder and appreciation), is also a terrific actor, going believably from sweet open kid to cold lean killer with a haunted aspect. “Man of Tai Chi” takes place in a deeply moral universe where our choices have spiritual implications.

The fighting ring is illegal. The cops (one in particular) close in on Donaka, who remains elusive and omniscient. Donaka understands that tai chi is not the usual fare in the martial arts underground, and he gets off on the fact that Tiger has sold out. That’s the turn-on, the power trip. Reeves isn’t in the film all that much, and there are a couple of extremely stiff scenes of dialogue, but he does get a very impressive fight scene with Tiger near the end. This is Tiger Chen’s picture all the way. You watch him transform, and you watch his soul go dark.

CinematographercElliot Davis films the fight scenes with thrilling immediacy: lots of long takes, so you realize you are actually seeing these guys actually do this, as opposed to watching something pieced together later in the editing room. The camera circles and rises and pulls back, moving horizontally and vertically with the movements of each fight. The filming is intuitive and visceral. There’s one masterpiece of a scene that takes place in a hidden night club floating in the bowels of a cargo ship in Hong Kong harbor. The setting is surreal: the circular stage painted with psychedelic dizzying swirls and the circular tables surrounding said stage, not to mention the bored elegant silent crowd, is reminiscent of the midnight theatre scene in David Lynch’s “Mulholland Drive” or the freaky tiered nightclub in Josef von Sternberg’s “Shanghai Gesture”. Each fight gets more dangerous. The stakes rise. Death is the only possible outcome. Reeves approaches the genre with respect and passion. “Man of Tai Chi” is hugely entertaining.

By Jessica Winter

Source: Film Comment

When is the audience allowed to laugh at a serious movie? How do you gauge whether the laughter expresses surprise, shock, nervousness, disdain, feigned superiority, genuine mirth, or some combination thereof? Take Werner Herzog’s films with his best fiend, Klaus Kinski: at a New York repertory screening of the deranged-conquistador saga Aguirre, Wrath of God a few years back, the patrons might as well have been watching The Hangover. Were they wrong? Or how about Abel Ferrara’s 1992 hell trip Bad Lieutenant: is it wildly inappropriate to laugh when Harvey Keitel’s depraved cop screams “You ratfucker!” at a church lady he mistakes for Jesus Christ? Is it wildly inappropriate not to laugh?

Herzog’s not-a-remake, Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans, tacitly addresses this dilemma. Like much of the Herzog-Kinski catalogue, it’s a case study in bug-eyed monomania, and like Ferrara’s original, it’s a descent into the swamplands of the human soul with a drug-addled, quasi-righteous, borderline-insane cop as your tour guide. Unlike either, the reboot appears to be a comedy, or something close to it. BL:POCNO has comedy props: singing iguanas, a “magic crack pipe,” Val Kilmer. It has comic refrains that become funnier with each iteration, including Nicolas Cage’s emphysematic laugh and—for reasons that are tough to explain concisely—the letter “G.” It has punch lines. (“Everything I take is prescription. Except for the heroin.”) It has, for lack of a better term, a Gator Cam. Best of all, it has Cage, a walking sight gag who throws out his back early and spends the rest of the film bathed in a cold sweat of cocaine and Vicodin, lumbering around the post-Katrina landscape like he’s got a jumbo-sized T-square surgically jammed between his shoulder blades.

Cage’s Terence McDonagh comes off as part Kinski-style holy fool, part standard-issue Rogue Cop Who Gets Results. He shuttles crookedly between his adorable coke-whore sweetheart (Eva Mendes), his alcoholic father (Tom Bower), Dad’s beery girlfriend (Jennifer Coolidge, impressively frowsy), and his 24-7 mission pursuing local crack kingpin Big Fate (Alvin “Xzibit” Joiner), who’s possibly the most affable and credulous drug lord in cinema history. (This ambitious lad is happy to show new friend McDonagh the would-be flagship of a future real-estate empire: “waterfront condos” sited on some godforsaken loading dock, where Big Fate’s henchmen currently dump the bodies of their victims.)

But BL:POCNO’s shaggy police procedural (the screenwriter is NYPD Blue and Law & Order alumnus William Finkelstein) is almost an afterthought, always secondary to the Passion of the Cage: stations include a pharmacy meltdown worthy of Julianne Moore in Magnolia, a scary-funny parking-lot shakedown of two club kids out on Daddy’s credit cards, and above all, a feat of witness intimidation involving an electric shaver and a nice old lady’s nasal cannula. Pawing absently at his face, sniffing at bags of evidence (usually pocketing them for later), and huffing crack with anyone who’s holding, McDonagh is a mass of primitive, unexamined desires. In the grip of both addiction and workaholism, he has an appetite but not a will, a brain but not a mind. He is, perhaps, reptile brain incarnate—hence those singing iguanas and surveillance-camera-eyed alligators, not to mention the lone little fish swimming sad circles in a glass in a dead boy’s room.

The Herzog version almost entirely eschews the religious iconography of BL 1.0, but McDonagh does occasionally experience the kind of ecstatic self-forgetting that saints and drug addicts have in common. The dopey bliss that washes over Cage’s face when he glimpses a break-dancing ghost or regales his starry-eyed girlfriend with childhood tales of “buried treasure” is the happiest gift this erratic actor has given us in a long time. Shot in New Orleans largely for the tax break, labeled Bad Lieutenant largely because the producers had rights to the brand name, and starring an actor who, not to put too fine a point on it, makes a lot of crap, Herzog’s movie has expedience and exploitation written all over it. But it’s too weird and unhinged and endearing—and, for all its sordid details, too ingenuous—to be anything but a labor of love.

Watch the film on Hoopla here: https://www.hoopladigital.com/title/12197641

By Tara Brady

Source: The Irish Times

Film Title: The Guest

Director: Adam Wingard

Starring: Dan Stevens, Maika Monroe, Brendan Meyer, Lance Reddick

Genre: Crime

Running Time: 99 min

Blue-eyed soldier boy David (Dan Stevens) arrives in a small New Mexican town to visit the family of a fallen comrade. The grieving mom (Sheila Kelley) notices that the young Iraq War veteran has appeared, as if from nowhere, but David’s “yes ma’am” manners soon put her at ease. The family are not in great emotional shape: dad has hit the bottle, teenager Luke is sullen and withdrawn, and his older goth sister Anna (Maika Monroe) stays in her room making mix-tapes.

Might their new guest allow the healing to begin? Perhaps. David soon makes himself useful by tackling Luke’s schoolyard tormentors, hanging out the household washing and carrying kegs around a party Anna attends. But Anna continues to suspect that David is not all that he seems to be.

She has no idea.

Adam Wingard is the mumblegore horror hotshot behind the better bits of the V/H/S portmanteau horror and the 2011 cult favourite You’re Next. The latter’s hefty profit margin – $25 million back from six figures – has allowed the hyphenate director, editor, cinematographer and writer to move up divisions with a budget of more than $1 million.

Being accustomed to producing his earlier, murkier movies for $20,000 or so, Mr Wingard knows well how to get more bang for your buck. Armed with something approaching a real budget, he now puts on one hell of a show. The Guest, a thriller that becomes a horror that transitions into a hilarious truncation of every 1980s action picture and back again, is as extravagant and ambitious a film as you’ll see all year. Picture Commando as a psychological thriller. Imagine Halloween as a theme park ride. Think Drive as a comedy.

A cleverly picked constellation of TV favourites – Downton Abbey’s Dan Stevens, LA Law’s Sheila Kelley, Fringe’s Lance Reddick – add some star wattage to an outrageous and outrageously entertaining hybrid.

Stevens keeps a poker-straight face as he delivers some of the year’s funniest lines. Maika Monroe’s screen magnetism is enough to keep Scar-Jo and J-Law awake during the long winter nights.

If Luc Beeson’s Lucy has left you jonesing for something that stands apart from the superheroes and straight-world toughs that populate the movieverse, then The Guest is a most welcome imposition.

Watch the film on Hoopla here: https://www.hoopladigital.com/title/13703180

INDIAN COUNTRY NEWS

"It is the duty of every man, as far as his ability extends, to detect and expose delusion and error"..Thomas Paine

Human in Algorithms

From the Roof Top

I See This

blog of the post capitalist transition.. Read or download the novel here + latest relevant posts

अध्ययन-अनुसन्धानको सार